Eßweiler

| Eßweiler | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Eßweiler | ||

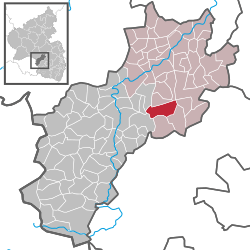

Location of Eßweiler within Kusel district  | ||

| Coordinates: 49°33′32″N 7°33′53″E / 49.55889°N 7.56472°ECoordinates: 49°33′32″N 7°33′53″E / 49.55889°N 7.56472°E | ||

| Country | Germany | |

| State | Rhineland-Palatinate | |

| District | Kusel | |

| Municipal assoc. | Lauterecken-Wolfstein | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Peter Gilcher | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 8.10 km2 (3.13 sq mi) | |

| Population (2015-12-31)[1] | ||

| • Total | 427 | |

| • Density | 53/km2 (140/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | |

| Postal codes | 67754 | |

| Dialling codes | 06304 | |

| Vehicle registration | KUS | |

| Website | www.essweiler.de | |

Eßweiler (German pronunciation: [ˈɛsvaɪlɐ], with a short E; also Essweiler) is an Ortsgemeinde – a municipality belonging to a Verbandsgemeinde, a kind of collective municipality – in the Kusel district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It belongs to the Verbandsgemeinde Lauterecken-Wolfstein.

Geography

Location

The municipality lies roughly 25 km north of Kaiserslautern, 15 km east of Kusel and 4 km west of Wolfstein at the foot of the Königsberg, a mountain in the North Palatine Uplands. Eßweiler sits at an elevation of 260 to 280 m above sea level, and has also given the dale in which it lies its name, the Eßweiler Tal.

In the village itself, the two streams, the Breitenbach and the Jettenbach, flow together to form the Talbach, which is fed by the Steinbach about 100 m beyond the municipal limit, thereafter flowing down to Offenbach-Hundheim, where it empties into the Glan.

Found around Eßweiler are some of the district’s highest mountains: the Königsberg (568 m), the Selberg (546 m), the Potschberg (498 m), the Bornberg (520 m) and the Herrmannsberg (536 m).

Eßweiler has 431 inhabitants and an area of 8.1 km². Land under agricultural use amounts to 39.5%, while 13.9% is used for residential and transport purposes. Another 46.1% of the municipal area is wooded, and 0.5% is open water.[2][3]

Neighbouring municipalities

Eßweiler borders in the north on the municipality of Oberweiler im Tal, in the northeast on the municipality of Aschbach, in the east on the municipality of Rutsweiler an der Lauter, in the southeast on the municipality of Rothselberg, in the south on the municipality of Jettenbach, in the southwest on the municipality of Bosenbach, in the west on the municipality of Elzweiler and in the northwest on the municipality of Horschbach. Eßweiler also meets the town of Wolfstein at a single point in the northeast.

Constituent communities

Eßweiler has only one outlying centre, called the Schneeweiderhof (Hof means “estate” in German, and the name takes the definite article), lying some 3 km from the village at an elevation of about 500 m above sea level on the Bornberg. Its history is tightly bound with the stone quarries that were established there beginning in the 1870s. Between 1922 and 1924, the then owners of the quarries, Basalt-Actien-Gesellschaft (a company that is still in business today, based then, as now, in Linz am Rhein and known as Basalt AG for short), built a workers’ settlement for quarry employees, the Kolonie, out of basalt stones. The complex is still fairly well preserved.

Owing to the great number of schoolchildren (all together 25 of them in seven grades in 1952), a school was set up at the Kolonie in 1952 in a purpose-built building, thus sparing the children the daily walk to the village and back. The school was, however, dissolved in 1965 owing to school reform.[4] Since the quarries were closed in 1970, the population figure on the Schneeweiderhof has been steadily shrinking; more and more flats are now unoccupied. On the other hand, the Schneeweiderhof is popular among hikers and daytrippers from the local area, if only to make a stop at the local inn.

Municipality’s layout

Eßweiler owes its current shape mainly to the time that followed the Thirty Years' War. It was built as a linear village (by some definitions, a “thorpe”) stretching along Hauptstraße (also known today as Landesstraße 372). In the village core, where the Breitenbach and Jettenbach meet to form the Talbach, another road, Krämelstraße, branches off as Landesstraße 369 to Jettenbach and on towards Landstuhl. Also in the village core stands the Protestant church, built in 1865. Next to it were the old school building and the old village hall, which was renovated and expanded in the 1960s. As early as 1935, the former alte Schul (“old school”) was supplemented with a new school building on the road leading out of the village towards Oberweiler im Tal. The village core was given a makeover in the 1980s when a new village square was laid out. Eventually, in the years 1994-1997, a village community centre was built right on this square. Leading out of both the former and current village core is the street “Im Läppchen”, the part of which on the Talbach’s right bank is known even today as the Judengasse (“Jews’ Lane”), a reference to the once important Jewish sector of the population in Eßweiler. Since the 1950s, the bridges leading across the brooks have been turned into culverts so that the crossing between the two highways – still known locally as a “bridge” – now bears little sign of its former shape. Branching off from Krämelstraße is a Kreisstraße that leads to the outlying centre of the Schneeweiderhof some 3 km away on the summit of the Bornberg. This road was expanded as Kreisstraße 31 in 1959 and renovated in 1994 and 1995. Until 1970, diorite was quarried at the Schneeweiderhof. The former quarry lands together with the Kolonie, a workers’ settlement for those who worked the quarries, built in 1923, may be described as an industrial monument. In 1988, the Kusel district began using the old quarries as the district dump. Just beyond the junction where the road branches off to the Schneeweiderhof, a new building development sprang up along Krämelstraße in the 1950s, which pushed the village’s built-up area outwards towards Jettenbach. Work on a further building development, “Auf Herrmannsmauer”, began in 1980 on the road leading out of the village towards Oberweiler im Tal, above Landesstraße 372. Currently, the municipality is putting its efforts into yet another new building development in the field known as “Rödwies” on Rothenweg. According to the 1987 census, Eßweiler has 161 residential buildings with 195 dwellings. Somewhat more than one third of these buildings date from before 1900. On Eßweiler’s outskirts, two Aussiedlerhöfe (singular: Aussiedlerhof – outlying farming settlements), the Königsbergerhof (below the Königsberg) and the Lindenhof (on the road leading out of the village towards Jettenbach). Near the Lindenhof, in the part of the municipal area called “Altbach”, the municipality wants to open a commercial area.

In the late 1980s, the Christliches Jugenddorfwerk Deutschlands (CJD) acquired a sizeable property in the village core. After the original idea of running a training centre for ecological farming fell through, the two buildings served as a way station for Aussiedler from East European countries. The CJD has also meanwhile housed trainees.[5]

History

Stone Age to Roman times

Within both Eßweiler’s and Rothselberg’s municipal limits, several Stone Age finds have been brought to light. Later, Celts settled here. They were forced out by Germanic tribes, who were in turn pushed out, over to the Rhine’s right bank, by the Romans. By the time the Gallic Wars ended locally, in 51 BC, the whole of the Rhine’s left bank was part of Roman Gaul. Unearthed in 1904, and bearing witness to Roman-Gaulish times, was a silver spoon decorated with doves, grapes and grapeleaves and inscribed “Lucilianae vivas”. Its origin is Roman, from about the 4th century.[6] The spoon is now to be found at the Historical Museum of the Palatinate (Historisches Museum der Pfalz) in Speyer, and is also early evidence of Christianity in the Palatinate (see Religion below). On the Trautmannsberg in 2002 and 2003, workers with the Office for Archaeological Monument Care (Amt für archäologische Denkmalpflege) undertook diggings to observe and preserve a Roman estate. Right next to the site, they unearthed ceramics and storage pits from pre-Celtic times (about 800 BC).[7] Moreover, in the early 20th century on the Potschberg, the building remnants of a Roman mountain sanctuary were found. The Romans withdrew from the region about AD 400, and the Alemanni who settled after them were eventually driven out by the Franks under King Clovis I (466-511). The whole region was part of the Reichsland, which was at the king’s own disposal, giving rise to the name Königsland, still used today.[8]

Middle Ages

Eßweiler most likely arose sometime between 600 and 800, which was the time when villages with names ending in —weiler came into being. In 1250 and 1296, Eßweiler had its first documentary mentions as Esewilre. Originally, the village lay not in the dale, but rather at the foot of the Königsberg, in what is now the field known as Kirchwiese. In earlier days, wall remnants were found. In the Middle Ages and Early Modern times, Eßweiler belonged to the Eßweiler Tal complex (Tal means “dale” or “valley”), a territorial unit comprising not only Eßweiler but also Oberweiler im Tal, Hinzweiler, Nerzweiler, Hundheim, Aschbach, Horschbach, Elzweiler and Hachenbach, all of which today lie within the Kusel district. A cleared area that included the greater part of the Eßweiler Tal was donated to Prüm Abbey in Prüm in the Eifel between 868 and 870.[9] The lordly seat was Hirsau, whose ancient church bears witness to this time. Later, the whole Dale was ruled by the Counts of Veldenz, who had split away from the Waldgraves. Their administrative seat was at first Nerzweiler; sometime between 1443 and 1477, it was moved to Hundheim.[10] The Offenbach Monastery and the old Hirsauer Kirche (the ancient church mentioned above) give a clue that the Eßweiler Tal was originally a monastic Vogtei region. The record shows that in 1150, the estates in Aschbach, Hachenbach and Hirsau were donated to the Offenbach Monastery by Reinfried von Rüdesheim as a provost’s realm of Saint Vincent’s Abbey in Metz; the Archbishop of Mainz confirmed this donation in 1289. Hirsau was until the 16th century a parish covering the whole Dale. In the 12th century, the Eßweiler Tal passed to Count Emich von Schmidtburg, who is said to be the one who endowed the comital line of Veldenz. In 1393, the Dale passed as a Wittum (widow’s estate) to Margarete von Nassau, Count of Veldenz Friedrich III’s wife.

Between Eßweiler and Oberweiler im Tal, the Sprengelburg (or Springeburg – a castle) was built about 1300. It was not standing very long before it was destroyed. The castle lords at the time were the Knights of Mülenstein (or Mühlenstein), vassals of the Waldgraves,[11] although little else is known about the castle’s history. Only in a 1595 description of the Eßweiler Tal written by state scrivener and geometer Johannes Hofmann on Count Palatine Johann’s behalf can anything be read about the Sprengelburg and its eventual destruction by merchants from Strasbourg. Today, only a ruin is left standing. It was restored by the municipality of Eßweiler in the 1980s after an American academic, Professor Thomas Higel from the University of Maryland, had unearthed some remnants in the 1970s that had lain under a heap of rubble. The castle lies on Landesstraße 372; the Eßweiler-Oberweiler municipal limit passes right through the castle grounds. It is still known today as the Altes Schloss, or “Old Castle”. It stands on a spur that juts out of the Königsberg, and the land drops off sharply to the brook that flows by through the dale. The lordly builders built their castle at the dale’s narrowest spot, which may have been done so that they could control the road that once ran through the dale. archaeological digs brought to light a rectangular arrangement of outer walls (roughly 15 × 20 m) with a round tower standing in the middle with a diameter of 8 m. This suggests that the complex was not a castle as such, but rather a well-developed watchtower. No special finds were unearthed in the course of digs. Only at the foot of the hill were potsherds found, although in the summer of 1978, Professor Higel’s team stumbled on a young woman’s skeleton; she might have died in the castle’s destruction. This find aroused much greater interest in the castle’s history. Perhaps, it was thought, the answer might lie in Johannes Hofmann’s old description, which contains, among other things, a detailed report about the castle’s destruction. The “Springeburg”, as Hofmann called it, met its fate in neither the Thirty Years' War nor the Nine Years' War (known in Germany as the Pfälzischer Erbfolgekrieg, or War of the Palatine Succession), but rather it was destroyed, supposedly sometime between 1350 and 1400, in the course of retaliatory measures – the Mülensteins were notorious as robber knights – undertaken by some Strasbourg merchants. Hofmann specifically mentioned a death in the incident, although it was a man, a Junker of Mühlenstein; presumably, though, others might have died with him.[12] Over the years, the political unity of the Eßweiler Tal broke ever further down, until in the 16th century, 14 vassals held sway in the villages. The highest landlords and vassals at this time were the Junkers of Scharfenstein. They, too, were vassals of the Waldgraves and they maintained a common administration and jurisdiction.[13]

Early Modern times

In 1595, the whole Eßweiler Tal passed to the Duchy of Palatinate-Zweibrücken, to which Eßweiler belonged until 1797, when the lands on the Rhine’s left bank were overrun and conquered by Napoleon’s forces, while a few villages passed back to the Waldgraves in 1755.[14]

The wars of the 17th and 18th centuries wrought great destruction and losses to the population. In the Thirty Years' War, there was no great amount of fighting, but many times various armies marched through the area, plundering and destroying; one mill in Eßweiler fell victim to their destructive ways (it was restored in 1661).[15] Between 1635 and 1638, the villagers also had the Plague to deal with, which had cropped up sporadically before this.

Subsequent wars, too, brought their own miseries as the region once again became a military route. In both the Franco-Dutch War and the Nine Years' War (known in Germany as the Pfälzischer Erbfolgekrieg, or War of the Palatine Succession), the region was occupied by French forces. There was repeated plundering and destroying.[16] By 1768, only 141 families lived in the Eßweiler Tal. In the years that followed, many inhabitants emigrated to North and South America or Eastern Europe.

Building work on a church began in Eßweiler in 1733. By 1745, there were once again two mills in the village (both of which still stand, and one of which was even still being run until the 1970s). In 1750, a fire wrought great damage to the village.[17]

Of the many settlements that arose in the expansions between 600 and 1200, more than half have not survived. As early as shortly after 1400, a few villages in the Eßweiler Tal were destroyed by “Armagnacs”. The inhabitants furthermore had to suffer under the great epidemics of the time. In 1564, the Plague supposedly claimed 200 victims of the 800 people then living in the Eßweiler Tal. In 1575, Eßweiler itself apparently had only 24 inhabitants left. In 1622, another wave of the Plague swept across the land during the Thirty Years' War leaving most villages all but depopulated. Time and again, as arranged by the lords who held the land, newcomers were brought in to settle the land again; from France, Switzerland and even the Tyrol they came, but the 1648 Peace of Westphalia failed to bring any calm to the land as French King Louis XIV waged his wars of conquest, turning the Palatinate into a battleground. Although the end of the politically and religiously motivated wars after 1700 soothed tensions somewhat, the land itself remained poor. Famines drove a great deal of the inhabitants to migrate to Habsburg-ruled Eastern Europe, Prussian Brandenburg, Pomerania and eventually overseas to North America. Many families from Eßweiler were among the emigrants.[18]

19th century

The outbreak of the French Revolution brought yet more war along with it. After Napoleon had conquered the area, Eßweiler belonged to France beginning in 1797, finding itself in the Department of Mont-Tonnerre (or Donnersberg in German), or more locally, Eßweiler was the seat of a mairie (“mayoralty”) in the Canton of Wolfstein and the Arrondissement of Kaiserslautern.

From 1816, after the Congress of Vienna, until the First World War ended, Eßweiler belonged to the Kingdom of Bavaria. Thereafter and until the state of Rhineland-Palatinate was founded in 1947, it belonged to the Free State of Bavaria.

In the early 19th century, the inhabitants fed themselves mainly by agriculture, but the population was rising markedly, which made poverty in Eßweiler all the more acute as there was a dearth of employment opportunities in the region. In 1803 there were 464 inhabitants, but by 1836 that number had risen to 614 (28 Catholics, 525 Protestants and 61 Jews), and by 1867 to 716 (14 Catholics, 617 Protestants and 85 Jews). Economic need and repeated famines, though, led in both the 18th and 19th centuries to several waves of emigration, which lasted into the 1920s. From Eßweiler, several branches of the family Gilcher (the current mayor’s surname), among others, emigrated to Brazil and the United States.[19]

It was in the 1830s that the Westpfälzer Wandermusikantentum, a musical movement that saw local Musikanten – literally “minstrels” – travel all over the world, began. Its heyday fell between 1850 and the First World War. Eßweiler was one of the main centres of what is now known as the Musikantenland, seemingly contributing a disproportionate share of these musicians. Some 300 musicians spread out from here in the 19th century and went throughout the world, mostly to North and South America, but also to Australia, China and Africa. Unlike the more permanent emigrants, most of these “wandering minstrels” eventually came back, even though for some, the journey could last several years. Well known musicians from Eßweiler include:

- Michael Gilcher (1822–1899), trumpeter, went to England and the USA, was later Eßweiler’s mayor.

- Hubertus Kilian (1827–1899), trombonist, went to among other places Australia, China (where he was named “Imperial Chinese Orchestra Leader”) and the USA.

- Rudolph Schmitt (1900–1993), clarinettist, stayed in the USA and became a sought-after clarinettist in several symphony orchestras.

Another income source came into play when hard rock deposits were discovered at the Schneeweiderhof. About 1840, a few villagers began making paving stones on the Kiefernkopf. The diorite out of which these were being made was distinguished by its ability to bear up against stresses, which led to the local paving stones becoming a sought-after product, much favoured by many cities and towns.[20]

Since 1900

In the beginning, the stone deposit was worked by many small quarrying businesses, until 1914, when they were all taken over by Basalt AG from Linz am Rhein, who proceeded to further expand the quarrying operations. In 1919, a ropeway conveyor to Altenglan was built to ensure efficient transport of the product. In 1923, the Kolonie was built, a workers’ settlement with roughly 50 dwelling units. In 1928, the operation had 567 employees. By the time of the outbreak of the Second World War, the workforce had shrunk to 320. By the early 1950s, there were still 190 workers employed at the quarries, but by the late 1960s, this had dwindled to only 68, although productivity had nevertheless grown considerably as a result of rationalization. Nevertheless, the operation was shut down for good in 1970, not least of all because of the unfavourable transport conditions. The Wandermusikantentum and hard-stone quarrying were crucial for development in the early 20th century.[21]

In 1907, the first watermain was laid, bringing water from a spring at the Trautmannsberg. This remained in service until the 1980s. Eßweiler, along with the Schneeweiderhof, was then hooked up to the long-distance water supply system. Eßweiler was connected to the electrical grid beginning in 1924.

In both world wars, Eßweiler lost many people. The inscription on the Eßweiler war memorial names 13 fallen and 2 missing soldiers from the First World War, but nothing is known about any destruction or civilian losses in the village itself. From the end of the Great War until 1946, Eßweiler belonged to the Free State of Bavaria (as opposed to the now defunct Kingdom).

On Kristallnacht (9–10 November 1938), the two last Eßweiler Jewish families’ houses were both invaded and thoroughly vandalized. Shortly thereafter, the village’s three remaining Jewish residents were taken away to the camps[14] (see also below). The village came through the Second World War more or less unscathed; only one building was damaged by an American tank. Nevertheless, according to memorial inscriptions, 51 soldiers from Eßweiler fell in the war. Particularly tragic was an accident that happened in February 1945, when some children and youths found a Panzerfaust left behind by retreating German soldiers and began playing with it. It exploded, killing five children. Several others were wounded, some seriously.

Since 1946, Eßweiler has been part of the then newly founded state of Rhineland-Palatinate. With the establishment of the Verbandsgemeinde of Wolfstein on 1 January 1972, the Bürgermeisterei (“Mayoralty”) of Eßweiler, which was also responsible for the neighbouring municipality of Oberweiler im Tal, was dissolved.

Today, Eßweiler is purely a residential community. The greater part of the roughly 450 inhabitants work in the surrounding towns.

Population development

Eßweiler’s population figures rose during the 19th century and reached 614 by 1838. Despite emigration and people moving away, the figures kept rising, reaching 683 by 1939. After the Second World War, in 1950, the population even reached as high as 724, not least of all because of refugees from central Germany and ethnic Germans driven out of Germany’s former eastern territories. In the time that followed, the population figures steadily dropped. While Eßweiler still had 687 inhabitants in 1961, this had fallen to 582 by 30 June 1997. The population is now well under 500.[22]

Population figures

At 31 May 2009, 431 persons in Eßweiler had their main residence in the municipality, 207 (48.03%) of whom were male and 224 (51.97%) of whom were female. Foreigners were 1.62% of the population, and 46 had their secondary residence in Eßweiler. [23]

The following table shows population development over the centuries for Eßweiler, with some figures broken down by religious denomination:

| Year | 1609[17] | 1803[24] | 1825[25] | 1835[25] | 1836[24] | 1867[24] | 1871[25] | 1893[26] | 1905[25] | 1938 | 1939[25] | 1961[25] | 1969[27] | 1974[27] | 1977[27] | 1980[27] | 1997[25] | 2007[23] | 2009[23] | 2009[25] |

| Total | 144 | 464 | 584 | 614 | 614 | 716 | 673 | 682 | 644 | 672 | 684 | 687 | 666 | 612 | 599 | 602 | 582 | 453 | 446 | 431 |

| Catholic | 37 | 19 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Evangelical | 501 | 665 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Jewish | 46 | – |

Age breakdown

The following age breakdown can be deduced from Eßweiler’s 31 May 2009 population figures:[23]

| Age | 2009 share (%) |

| 0-9 | 4.87 |

| 10-19 | 13.92 |

| 20-29 | 7.89 |

| 30-39 | 9.75 |

| 40-49 | 19.26 |

| 50-59 | 16.47 |

| 60-69 | 11.37 |

| 70-79 | 10.91 |

| 80+ | 5.57 |

Population by religious affiliation

At 31 May 2009, the 431 people whose primary residence was in Eßweiler adhered to the following faiths:[23]

| Denomination | Number | Percentage |

| Evangelical | 330 | 76.57 |

| Catholic | 38 | 8.82 |

| Free religious state community of the Palatinate | 2 | 0.46 |

| other | 3 | 0.70 |

| none | 48 | 11.14 |

| no answer | 10 | 2.32 |

Municipality’s name

The village’s name, Eßweiler, has the common German placename ending —weiler, which as a standalone word means “hamlet” (originally “homestead”), to which is prefixed a syllable believed by writer Ernst Christmann to have arisen from an old German man’s name, Ezzo (or Ezo, Azzo or Azzio), and thus the name would originally have meant “Ezzo’s Homestead”,[28] meaning that Eßweiler owes its modern name to one of its oldest settlers. Given the other forms of Ezzo’s name, Eßweiler may have been named Aßweiler at one time, but there is no historical record to confirm this.[29] In the beginning, the village lay on the cadastral area now called “Kirchwiese”, where once wall remnants were also found. In 1296, Eßweiler had its thus far earliest known documentary mention in a document from the Counts of Zweibrücken, which mentions the village of Esewilr.[30] The area had been, however, settled earlier than that, as the Stone Age to Roman times section, above, details.

Religion

Christianity

The Roman silver spoon found in 1904, mentioned above, is reckoned to bear witness to early Christianization, for the doves pecking at grapes with which the spoon is decorated were described in the literature about the find as a typically Christian emblem.[6] It shows at least there was contact with Christianity at that time.

In an ecclesiastical sense as well as a political one, the Eßweiler Tal was a unit. Until the Reformation, the Catholic faith predominated. The ecclesiastical hub was Hirsau. The parish church was the Hirsauer Kirche, a 12th-century church near Hundheim, and the whole Eßweiler Tal was its parish. This unity was lost in the Reformation, for in 1544, the villages of Eßweiler, Hinzweiler and Oberweiler im Tal were split away from the old parish and made into a new parish of their own based at Hinzweiler; the church in that village became the parish church, and that was also where the parish priest lived. This separation came along with the spread of Protestantism once the Waldgraves converted to Lutheranism.[31] In 1595, the Dale passed to Palatinate-Zweibrücken, which required, under the principle of cuius regio, eius religio, that everyone convert to the Reformed faith. It was in this time that the parish of Hinzweiler, which was also responsible for Eßweiler, was headed by a pastor from Austria named Pantaleon Weiß (he called himself Candidus). He had studied in Wittenberg under Philipp Melanchthon and harboured Reformed ideas. Originally, the whole Eßweiler Tal had only one graveyard, in Hirsau. Eßweiler, however, had its own graveyard by 1590. It can be assumed that Protestantism was quite widespread at the time, as it was the lords’ belief. In 1601, Eßweiler passed to the parish of Bosenbach, which after the Thirty Years' War was united with the parish of Hinzweiler. Thereafter, the local ecclesiastical seat was once again Hinzweiler. According to the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick, all villages in the Eßweiler Tal were parochially merged with Eßweiler. The Lutheran faith had not vanished utterly: In 1709, when the Duchy of Palatinate-Zweibrücken lay under Swedish rule, the Lutheran Church established its own parish for the Eßweiler Tal villages[32] to which, in fact, more than twenty villages belonged. The small Lutheran communities in Wolfstein and Roßbach were for a while tended by Eßweiler. In 1746, Eßweiler passed back to the parish of Bosenbach. This was not changed again until 1971, when Eßweiler passed to the parish of Rothselberg, to which it still belongs now, along with Rothselberg and Kreimbach-Kaulbach.

From 1758 to 1763, Johann Julius Printz was the pastor in Eßweiler, and from 1810 to 1817 it was Johann Heinrich Bauer. The Catholics’ share of the population was quite small in Eßweiler. In 1836 and 1837, Eßweiler had 614 inhabitants, of whom 28 were Catholic, 525 were Protestant and 61 were Jewish. As early as 1821, the Eßweiler parish church became a branch of Bosenbach. One of the best known pastors was Christian Böhmer (1823-1877). Born in Kusel, he came to Bosenbach in 1872 and earned himself some measure of fame through his literary endeavours. The Catholics were at this time tended by Wolfstein, while the few Catholics in the Eßweiler Tal before then belonged to Lauterecken, where there was a simultaneous church as early as 1725.[33]

The Jewish community

Important in Eßweiler at one time was the rather great share of the population represented by Jews. Jewish families are known to have lived in Eßweiler in 1680, 1698, 1746, 1776 and 1780. In 1688, there were four Jewish families living in Eßweiler. Their numbers grew steadily over the years until in the 1860s, Eßweiler had one of the biggest Jewish communities in the Kusel district. In 1789, a synagogue in the village was mentioned. The synagogue, locally known as the Judenschule, stood on the Judengasse (“Jews’ Lane”); the building is still standing. In 1867, the Jewish population numbered 85.[24] The number fell steadily over the years that followed as many inhabitants moved to the cities. On 24 January 1906, the Eßweiler Jewish worship community was dissolved. The remaining Jewish inhabitants, the two families of Isidor and his brother Sigmund (or Siegmund) Rothschild, joined the Kusel worship community.[34]

On Kristallnacht (9–10 November 1938), Brownshirts from Altenglan and Theisbergstegen, reinforced by a few NSDAP followers from Jettenbach and Brownshirts from Kusel who happened to be going about in the district destroying Jewish property, thronged into these two men’s houses and laid them waste.[34] Shortly thereafter, the village’s three remaining Jewish residents, the widower Isidor Rothschild, his brother Sigmund and Sigmund’s wife Blondine were taken away to the camps.[14] The last two named are believed to have died at Theresienstadt.[35] Two of their four daughters, too, were murdered in the camps.[36] The other two, and also Isidor’s son, survived the Holocaust and later lived in the United States.

There was a synagogue in the village, known popularly as the Judenschule. It was mentioned as early as 1789.[37] The street on which it stood is to this day popularly known as the Judengasse (“Jews’ Lane”). The synagogue was let out as a dwelling in 1902 and then auctioned in 1907.[38] The building is still standing, but it is now a house, and bears no sign of its original function. In the neighbouring building, renovation work in the 1960s unearthed the remains of a mikveh.

Jewish family names represented in the village were, among others, Rothschild, Loeb, Hermann, Wolf, Dreifuß, Lazarus, Herz and Ehrlich.

The Jews had their own graveyard in Hinzweiler, which was transferred to the Eßweiler community’s ownership in 1904, but later, they also buried their dead in Kaiserslautern.[38][39]

Politics

Eßweiler has belonged since 1 January 1972 to the then newly formed Verbandsgemeinde of Wolfstein.

Municipal council

The council is made up of 8 council members, who were elected by majority vote at the municipal election held on 7 June 2009, and the honorary mayor as chairman.[40]

Mayor

Eßweiler’s mayor is Peter Gilcher, and his deputies are Monika Riesinger and Hugo Spohn.[41]

Mr. Gilcher has held office since 2004, and was reelected on 7 June 2009.

Coat of arms

The German blazon reads: In Gold ein blauer Schräglinkswellenbalken, oben rechts eine rote schwebende Zinnenburg mit rotem Zinnenturm, links unten zwei gekreuzte schwarze Steinabbauhämmer.

The municipality’s arms might in English heraldic language be described thus: Or a bend sinister wavy azure between a castle and a tower both embattled gules masoned sable and a hammer and pick per saltire of the last.

The three charges in the arms are a castle, which represents the Sprengelburg or Springeburg, a “bend sinister wavy”, which represents the Talbach, which begins in the village with the merging of two other streams, and a crossed hammer and pick, which represent the old quarries in the outlying centre of the Schneeweiderhof.

The arms have been borne since 13 October 1982 when they were approved by the now defunct Regierungsbezirk administration in Neustadt an der Weinstraße.[42]

Culture and sightseeing

Buildings

The following are listed buildings or sites in Rhineland-Palatinate’s Directory of Cultural Monuments:[43]

- Protestant church, Läppchen 1 – Baroque aisleless church, 1733, tower with tent roof, 1865, architect Johann Schmeisser, Kusel; organ by E.F. Walcker & Cie. Ludwigsburg from 1869; stone fountain, 1857

- Near Läppchen 1 – warriors’ memorial 1914-1918 and 1939-1945, fountain complex, 1927, by Karl Dick, Kaiserslautern, expanded after 1945

- Mühlgasse 5 – former gristmill; one-floor sandstone-framed plastered building on raised basement, 1870; technical equipment from 1920s/1930s, turbine from 1950s

- Former workers’ colony of the Schneeweiderhof, west of the village on the Hermannsberg (monumental zone) – dwelling blocks for the quarry workers, two- and three-floor Swiss chalet style buildings of basalt quarrystone, round the back a farm and goat pens, 1922-1924, architects Heinrich Marrat and Eduard Scheler, Cologne

Castle Sprengelburg ruin

Between Eßweiler and Oberweiler im Tal on an outlying hill of the Königsberg, right on Landesstraße (State Road) 372, stands the Sprengelburg (or Springeburg). Judging from the remnants, it was built about 1300 and was soon thereafter destroyed in a feud against the Knights of Mülenstein, who were the castle lords, occasioned by their activities as robber knights. Right up until the 1970s, the site was known simply as am alten Schloss (“at the Old Castle”) and the whole ruin was buried under an earthen hill, quite hidden from sight, and with trees growing on it. The ruin’s current appearance is the result of restoration measures undertaken from 1976 to the mid-1980s initiated by the State Office for Monument Care (Landesamt für Denkmalpflege) in Speyer.[11] Since 1983, the ruin has been listed as an architectural monument.

The Kolonie

In the quarries on the Schneeweiderhof, sometimes up to 500 people were employed until the mid 20th century. They came from their homes in the surrounding villages to the mountain, and went back again each day, on foot, some of them walking five or six kilometres. Between 1922 and 1924, the quarry owners, Basalt AG, Linz am Rhein, built a workers’ settlement on the Schneeweiderhof out of basalt stones quarried on site. It is known locally as die Kolonie. The complex is made up of a three-floor main building and two wing buildings, which stand somewhat nearer the road. Through driveways with round arches, one reached the farms behind the complex, where there were goat pens and chicken coops. The complex’s outer appearance has been largely preserved from how it originally looked.[17] Many of the flats, however, are now empty.

Evangelical church

In the village centre stands the Evangelical church. The nave, work on which began in 1733, is still standing. The ridge turret, which was falling into disrepair, was replaced with a tower in 1865. Inside is an organ by E.F. Walcker & Cie. Ludwigsburg from 1869. It has been preserved unchanged from its original state.[17]

Cultural life

Cultural life in Eßweiler was in days of yore characterized by the schools, not least of all by the Latin school. From old documents come accounts even of theatrical productions in Eßweiler. Moreover, Eßweiler’s cultural life reached a high point in the 19th century with the emergence of the travelling musician industry (Wandermusikantentum). Musicians from Eßweiler went throughout the world. Among the 19th century’s best known orchestra leaders were Hubertus Kilian and Michel Gilcher. In the 20th century there was Jakob Meisenheimer, who travelled to almost every part of the globe. Also enjoying fame were Jakob Hager who, among other things, played at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, and Rudolph Schmitt, who worked for many years as a clarinettist for the world-famous orchestras in Chicago and San Francisco.[44]

Clubs

Given that there was a strong “musical industry” in the village at the time, it was no accident that there was a music club in Eßweiler as early as the 19th century. The treasurer’s book from the Mackenbach music club lists for the year of the Eßweiler club’s founding, 1883, an entry according to which an emissary was sent to Eßweiler to fetch the club’s bylaws. The music club continued to exist up until the time of the Weimar Republic, but then, by and by, it broke up. In 1990, the old Musikanten tradition in Eßweiler was revived by the founding of the “Talbachmusikanten” music club. The youth orchestra, Jugendorchester Eßweiler/Jettenbach, also belongs to this. Eßweiler’s oldest club is the Gesangverein 1888 Eßweiler e. V., a singing club. According to a 1942 record kept by the Deutscher Sängerbund (German Singers’ Association), it was founded as a men’s singing club in 1888. In its early days, the conductor was usually the local schoolteacher. In 1925, another singing club was founded, the Arbeiter Gesang- und Unterstützungsverein (“Workers’ Singing and Support Club”), whereupon the original singing club became known as the bürgerlicher Gesangverein (“civic singing club”). After Adolf Hitler’s 1933 seizure of power, the two clubs were actually forced into a merger under the terms of Gleichschaltung. The new, merged club was active until 1942. In 1946 came the refounding of the original club, which did not come off altogether well, as the French occupational authorities demanded, among other things, a French translation of the club’s charter. Beginning in the mid-1960s, it was becoming ever harder to find new blood for the singing club. Thus, in 1967, a women’s choir was founded and the men’s singing club became a mixed singing club. This served only to stave the problem off for a while, but by the 1990s, the singing club decided that it would be a good idea to form an association with the Gesangverein Horschbach. A major figure in the singing club was Oswald Henn, who from 1925 (then as part of the Workers Singing Club) to 1981 was the conductor.[14] From 1902 until the late 1960s, the singing club also staged theatrical productions. When a theatre group was founded in 1998, this tradition was once again continued.

In 1924, the bürgerlicher Sportverein Eßweiler (“Eßweiler Civic Sport Club”) was founded. In 1928, a gymnastic department and a girls’ squad were added, and thus arose today’s name, Turn- und Sportverein Eßweiler (“Eßweiler Gymnastic and Sport Club”). After the Second World War, the club was newly founded as a football club, although at first, owing to a lack of players, an association had to be formed with Rothselberg and Kreimbach-Kaulbach. Beginning in 1949, there were enough players for Eßweiler to field its own team. In 1957, the team rose to the Kusel B Class. In the 1960s, the lack of new blood became noticeable. The team rallied, however, and since 1968, there has been a playing association with Rothselberg. Since 1988, the association, SG Eßweiler-Rothselberg, has been playing once again in the Kusel B Class or Kreisliga.

The Landfrauenverein (“Countrywomen’s Club”) has been active in Eßweiler since 1962. In the early 1970s, the Heimat- und Verkehrsverein (“Local History and Transport Club”) was founded, which runs the Landscheidhütte and to which the theatre group also belongs. To support the fire brigade, the Feuerwehrförderverein „St. Florian“ Eßweiler (“Eßweiler Saint Florian Fire Brigade Promotional Association”) was founded. Other clubs in the municipality are the Alten- und Krankenpflegeverein (club for care of the elderly and infirm), the local SPD association and the Luftsportverein Eßweiler (vorm. Landstuhl) e. V. (air sports).

The following clubs, with founding date and membership, are currently active in Eßweiler:

- Turn- und Sportverein Eßweiler (gymnastic and sport club), founded in 1924, 125 members;

- Gesangverein 1888 Eßweiler (singing club), founded in 1888, 85 members, 25 active and 60 passive; since 1993 there has been an alliance with the Horschbach singing club;

- Landfrauenverein (countrywomen’s club), founded in 1962, 47 members;

- Feuerwehrförderverein (fire brigade promotional association), founded in 1983, 35 members;

- Heimat- und Verkehrsverein (local history and transport club), founded in 1972, 40 members;

- Musikverein Talbachmusikanten (music club), founded in 1990, 65 members, 35 active and 30 passive;

- Krankenpflegeverein (club for care of the elderly and infirm);

- Ortsverein der Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschlands (Social Democratic Party of Germany local branch).

Also closely associated with Eßweiler’s club scene is the Luftsportverein Landstuhl (Landstuhl Air Sports Club), which has been maintaining a glideerport at the cadastral area called “Striet” since 1964.[45]

Economy and infrastructure

Economic structure

Until the 20th century, agriculture was the mainstay of the local people’s livelihood. In 1833, the following acreages were noted:

| Crop/Use | Area in Morgen | Area in hectares |

| Cropfields | 1365 | 433.5 |

| Potatoes | 210 | 66.7 |

| Gardens | 7 | 2.2 |

| Fodder crops | 133 | 42.2 |

| Vegetables | 314 | 99.7 |

How great the extent of the meadowlands was is, however, unknown.[24]

Handicrafts arose insofar as they were needed to support the main endeavour, farming. In the earlier half of the 20th century, Eßweiler still had bakers, butchers, saddlers, cabinetmakers, tailors, shoemakers, painters and plasterers.

Beginning about 1830, the Wandermusikantentum – the “minstrel” tradition for which the area is famous – was growing in importance in the West Palatinate, and Eßweiler was becoming one of the great centres of the Musikantenland (see above). Besides this Wandermusikantentum, though, another musical enterprise also arose in Eßweiler, albeit on a small scale. This was the craft of making musical instruments.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, many mines arose around Eßweiler. Of greatest importance to Eßweiler, however, were the hard-rock deposits on the Schneeweiderhof, where citizens from Eßweiler first established quarries beginning in 1870. The main product was paving stones. In 1914, Basalt AG, Linz am Rhein bought up the quarries. A transport problem lay in the stones’ having to be laboriously carted overland to the railway stations in Kreimbach or Altenglan, but this was solved in 1919 with the opening of a five-kilometre-long ropeway conveyor to Altenglan. From time to time, up to 500 people from the surrounding villages were working at the quarries. Work permanently ceased there in 1970.[46][47]

The end of the Wandermusikantentum after the First World War made itself felt in its effect on job opportunities. After the Second World War, the formerly common livelihood of farming was shifted to a secondary position, or in some cases it vanished utterly as agriculture itself lost more and more of its importance, although two Aussiedlerhöfe (singular: Aussiedlerhof – outlying farming settlements) were established in the 1960s. By 2007 there were only eight agricultural operations covering an area of 84 ha (34.8% cropland and 65.2% meadow or grazing land).[2]

Another sector of the population worked at the K.O. Braun bandage factory in Wolfstein. To be sure, there were several small businesses in Eßweiler from the 1950s to the 1990s, but these did not truly weigh in the balance as far as job opportunities were concerned. Given this dearth of work, more and more workers became commuters. In the mid-1960s, Opel opened a plant in Kaiserslautern, which promised jobs for workers throughout the region. This would have been welcome in Eßweiler, especially after the quarries were shut down in 1970.[48]

Most of the inhabitants today work in nearby villages, towns or cities such as Wolfstein, Kusel or Kaiserslautern. Most drive, for despite considerable improvement to local public transport, it can still be problematic. Several small businesses have set up shop in Eßweiler, among others two bus operators, several craft businesses, the district dump on the Schneeweiderhof, which began operations in 1988, and the Christliche Jugenddorf Wolfstein (“Wolfstein Christian Youth Village”).

Retail trade and dining

In earlier times, the village had all that it needed for basic food supplies. There were several butcher’s shops and bakeries. During the heyday of the Wandermusikantentum, the musician Adolph Schwarz ran a music shop. Until the mid-1970s, there were still three grocery shops in Eßweiler, two butcher’s shops and a bakery. Nowadays there are only one food shop and one branch bakery.

Until the early 1970s, there were four inns in Eßweiler, and another one on the Schneeweiderhof. There are now only two – one in the village itself and the one on the Schneeweiderhof – and the local history club’s stall, which is open afternoons.

Public institutions

Between 1967 and 1969, the town hall was built. Today it houses the municipal council chamber, a branch of the district savings and loan association (Kreissparkasse) and a bakery branch, and it is also used by local clubs for small-scale events. A youth meeting centre has also been set up in the basement. Right next door, a fire station was built in 1988. After the municipality bought an agricultural property and tore the buildings down, it built a village square in the village centre in 1987.

On the lands occupied by the district dump on the Schneeweiderhof, there has been since 2005 the “Eßweiler” weather station, run by Meteomedia AG. As well, a four-hectare area was given over to a solar plant in November 2008; its output is 1.5 MW, and it is run by Neue Energie Pfälzer Bergland GmbH, a joint venture by Pfalzwerke AG and the District of Kusel. Also standing on the Schneeweiderhof is the 151 m-tall Bornberg transmission tower.

Bürgerhaus Eßweiler

Since there was no longer any room for large-scale events in Eßweiler – the former dance halls in the old inns had over time all been converted into dwellings – planning began in the early 1990s to build a village community centre, the Bürgerhaus Eßweiler. Originally it was to have been a new building on the way out of the village going towards Jettenbach, but while planning was still ongoing, an agricultural property in the village centre, complete with a house, a farm and a barn with stalls, was offered for sale. The municipality acquired the property and planning then took a new turn.

The foundation stone was laid on 2 June 1995. Mostly by Eßweiler citizens’ own volunteer work, the buildings were converted into a village community centre. The old building material was thereby preserved and integrated: the former house now houses the lavatory complex, several smaller event rooms and, in the vaulted cellar, the bar. The barn was gutted and now contains the actual event hall. Between the two, a new building went up. It contains the reception area, a vestibule and a commercial wing with a kitchen, a serving counter and storage rooms.

Education

There was no school as such in the Eßweiler Tal in the 16th century, but it is clear that children were being taught by clergymen. This was a job to which the clergymen were not strongly drawn, for their dwellings – where they would have had to hold lessons – were quite small and in the summertime they had to work the parish plot. In the late 16th century, though, the call to education was roused by the spread of humanistic and reform-minded ideas. A 1572 document hints at the existence of a school in Eßweiler. In 1604, the Eßweiler parishioners sent a petitionary letter to the lord who was responsible, namely Duke Johannes II (“the Young”), asking for a Latin school to be established. The Duke answered the request with a decree on 31 May 1604. The resulting Latin school was, however, lost in the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648). Theodor Zink reports of a Greek inscription on the arch above the doorway of the former parish cellar; it was apparently still preserved as late as 1818. After the ravages of the Great War, Eßweiler may have got a new school, but whatever the truth, teachers’ names are known from this time. During the 20th century, there was a two-stream primary school in Eßweiler, which in the beginning was housed at the old schoolhouse on the street “Im Läppchen”.

In 1936, a new schoolhouse was built on the way out of the village going towards Oberweiler im Tal, while the old school was still used until the 1950s. Until then, schoolchildren had attended classes in a building in the village centre and also at the town hall. This new schoolhouse, which over the years underwent many conversions, was used until 2002. In 1956, an upper floor was added to the new schoolhouse.

Between 1952 and 1965, the Schneeweiderhof had its own school. It was opened on 2 November 1952, it had 43 pupils and it had one room. Hitherto, children had had to walk 3 km each day to the village (and of course 3 km back) every day to school. On 25 August 1965, this school was closed and schoolchildren in year levels 1 to 4 then went to the primary school in Eßweiler, while those in year levels 5 to 8 went to the Mittelpunktschule (“midpoint school”, a central school, designed to eliminate smaller outlying schools) in Wolfstein.

This Mittelpunktschule in Wolfstein was founded in 1965 after a trial year in 1962/1963. Since then secondary-level students have been taught there. The primary school stayed in Eßweiler. With the founding of the Verbandsgemeinde of Wolfstein in 1971, schooling was also somewhat reorganized. Founded for the municipalities of Eßweiler, Oberweiler im Tal and Hinzweiler was the Grundschule Eßweilertal with school locations in Eßweiler and Hinzweiler. Eventually, in the 1980s, the Königsland-Grundschule was founded for the municipalities of Eßweiler, Hinzweiler, Jettenbach, Oberweiler im Tal and Rothselberg with three initial locations at Eßweiler, Jettenbach and Rothselberg; the Jettenbach location was later closed. At the beginning of 1997, the Königsland-Grundschule had 134 pupils in 8 classrooms. The various locations and, particularly, the lack of room, were grounds for planning a new school building. Thus, since the beginning of the 2002 school year, children from Eßweiler, Rothselberg, Jettenbach, Oberweiler im Tal and Hinzweiler formerly attending primary schools in Eßweiler, Jettenbach and Rothselberg have had a new, modern school building at their disposal, the Grundschule Königsland in Jettenbach.

Beginning in 1972, the municipality of Eßweiler ran, in the framework of a special-purpose association founded on 24 August of that year, a kindergarten in Jettenbach in collaboration with the municipalities of Jettenbach, Rothselberg, Oberweiler im Tal and Hinzweiler. Since 1997, Eßweiler and the neighbouring village of Rothselberg have been jointly running a kindergarten, called Spatzennest (“Sparrow’s Nest”) in the latter village. The sponsor is the Rothselberg Evangelical church community.[49]

Further schooling in the area is to be had at the Realschule plus Lauterecken-Wolfstein, the Realschule plus Kusel, the Gymnasien in Kusel and Lauterecken and the school centre in Kusel on the Roßberg with its Hauptschule, vocational school and Wirtschaftsgymnasium (business Gymnasium – see Education in Germany). The nearest colleges are the Fachhochschule Kaiserslautern and the Kaiserslautern University of Technology.

Transport

Running through Eßweiler is Landesstraße (State Road) 372, known locally as Hauptstraße (“Main Street”). It leads from Rothselberg to Offenbach-Hundheim. Joining to Hauptstraße in the village centre is Landesstraße 369, known locally as Krämelstraße. It leads to Jettenbach, and Kreisstraße (District Road) 31 branches from it at the Schneeweiderhof. It was built in 1959. The Kaiserslautern West interchange onto the Autobahn A 6 (Saarbrücken–Mannheim) lies 25 km away. It is 20 km to the Kusel interchange onto the Autobahn A 62 (Kaiserslautern–Trier), and likewise 20 km to the Sembach interchange onto the Autobahn A 63 towards Mainz. Furthermore, Bundesstraßen 270 (near Kreimbach-Kaulbach, roughly 6 km), 420 and 423 (in Altenglan, roughly 10 km) are right nearby.

Eßweiler belongs to the VRN. It is served by bus routes 140, 272, 274 and 275. The nearest railway station is found in Kreimbach-Kaulbach on the Lauter Valley Railway (Lautertalbahn), some 7 km away. Trains from there run to Kaiserslautern Central Station (Hauptbahnhof).

Gliderport

Above the village lies the Eßweiler Gliderport, run by the Eßweiler Air Sports Club. It was built in 1963, and is designed for gliders, motorgliders and ultralights. Motorized aircraft may only use the field if their takeoff weight is two metric tons or less, and they have an aerotow coupler.

Famous people

Sons and daughters of the town

- Michael Gilcher (1822–1899), wandering minstrel

- Rudolph Schmitt (1900–1993), clarinettist

Famous people associated with the municipality

- Hubertus Kilian (1827–1899), wandering minstrel, born in Jettenbach, died in Eßweiler

- Alexander Ulrich (1971–), Member of the Bundestag, grew up in Eßweiler.

References

- ↑ "Gemeinden in Deutschland mit Bevölkerung am 31. Dezember 2015" (PDF). Statistisches Bundesamt (in German). 2016.

- 1 2 Statistisches Landesamt Rheinland-Pfalz: Data for Eßweiler

- ↑ Location

- ↑ Schultagebuch des Lehrers Egon Fickeisen

- ↑ Municipality’s layout

- 1 2 Grünenwald L.: Urkunden und Bodenfunde zur Frühgeschichte der Pfalz, Palatina, Jg. 1926, S.212

- ↑ Lanzer, Rudi: Bei Grabungen Reste römischer Villa frei gelegt, Die Rheinpfalz, 11. Januar 2003

- ↑ Antiquity

- ↑ Rothenberger/Scherer/Stab/Keddigkeit: Pfälzische Geschichte Teil 1, Institut für pfälz. Geschichte und Volkskunde, Kaiserslautern, 2001, S. 114/115

- ↑ Dolch M.:Hundheim am Glan. Hintergründe eines Namenswechsels im hohen Mittelalter, Westricher Heimatblätter Jg. 20 (1989), S. 79

- 1 2 Daniel Hinkelmann: Die Ritter Mülenstein von Grumbach (1318–1451) und ihr Schloß Springeburg (nach Erkenntnissen bis April 1978). Westrich Kalender 1979

- ↑ Middle Ages

- ↑ Hofmann, Johann: Gründliche und wahrhaftige Beschreibung des Eßweiler Thals, wie derselbig mit seinen Bezirken und Grenzen inwendig und auswendig im gleichen mit Gebirgen, Wäldern, Rotböschen, Heck, Thälern, Brunnen, Weyern, Bächen, Flüssen und auch mit alten und neuen bewohnten Örtern und Dorfschaften gelegen ist. Gemacht nach der rechten geometrischen Art und Weise durch Johann Hofmann, der Zeit Kellern zu Lichtenberg anno 1595

- 1 2 3 4 Dr. Rudi Emrich: Zur Geschichte des Dorfes Eßweiler von den Anfängen bis ins 20. Jahrhundert. In: Festschrift zum 100 jährigen Vereinsjubiläum des Gesangvereins Eßweiler. 1990

- ↑ Weber, F.W.: Bauernmühlen an den Nebenbächen des Glan, Westrichkalender 1986, S. 82

- ↑ Zink, A.: Chronik der Stadt Lauterecken, 1968

- 1 2 3 4 Kulturdenkmäler in Rheinland-Pfalz Band 16: Kreis Kusel. Herausgegeben im Auftrag des Ministeriums für Kultur, Jugend, Familie und Frauen vom Landesamt für Denkmalpflege, ISBN 3-88462-163-7, Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, Worms 1999

- ↑ Early Modern times

- ↑ Auswanderungen der Familie Gilcher nach Nord- und Südamerika von Friedrich Hüttenberger im Internet

- ↑ 19th century

- ↑ Since 1900

- ↑ Population development

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gemeindestatistik aus dem landeseinheitlichen System EWOISneu, über http://www.rlpdirekt.de/

- 1 2 3 4 5 W. Schlegel/A. Zink: 150 Jahre Landkreis Kusel, Otterbach - Kaiserslautern 1968

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Eßweiler’s population development

- ↑ Bayr. Jahrbuch, Kalender für Bureau, Comptoir und Haus, München 1893

- 1 2 3 4 Westrichkalender Kusel, jeweiliges Jahr, Herausgeber Landkreis Kusel

- ↑ Christmann E.: Die Siedlungsnamen der Pfalz, Teil 1, 2. erw. und verbesserte Auflage, Speyer 1968, S. 150

- ↑ Municipality’s name

- ↑ Regesten der Grafen von Zweibrücken, nach Carl Pöhlmann bearbeitet durch Anton Doll, Speyer 1962, S. 121

- ↑ Cappel, Michael: Streifzüge durch drei Kirchenvisitationen im Eßweiler Tal, Westrichkalender Kusel, 1989, S. 94-99

- ↑ H. Matzenbacher: Pfarr- und Schulgeschichte der Stadt Wolfstein. Wolfstein 1966

- ↑ Christianity

- 1 2 „...auf Lastwagen fortgeschafft“, Herausgeber: Bündnis gegen Rechtsextremismus, Kusel, 2008

- ↑ Gedenkbuch - Opfer der Verfolgung der Juden unter der nationalsozialistischen Gewaltherrschaft in Deutschland 1933-1945, Bundesarchiv, Koblenz 1986 (E-Mail von Wiliam Gicher mit Textauszug)

- ↑ „Digital Monument to the Jewish Community in the Netherlands“ im Internet

- ↑ Arnold, H.: Von den Juden in der Pfalz, Speyer 1967

- 1 2 Bernhard Kukatzi: Der jüdische Friedhof in Hinzweiler, Landau 2008

- ↑ The Jewish community

- ↑ Kommunalwahl Rheinland-Pfalz 2009, Gemeinderat

- ↑ Eßweiler’s council

- ↑ Description and explanation of Eßweiler’s arms

- ↑ Directory of Cultural Monuments in Kusel district

- ↑ Cultural life

- ↑ Clubs

- ↑ Cappel, Michael: 100 Jahre Gesteinsabbau - Geschichte und Bedeutung für die Region, Westrichkalender 2005

- ↑ Lanzer, Rudi: Steinbruchbetrieb Eßweiler, Westrichkalender 1963

- ↑ Economic structure

- ↑ Education

Also based on personal oral communication between citizens of Eßweiler and the writer of the original German Wikipedia article from which this article is partly translated.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eßweiler. |

- Municipality’s official webpage (German)

- Brief portrait of Eßweiler with film from Hierzuland at SWR Fernsehen (German)