Eurasian (mixed ancestry)

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

Official population numbers are unknown; United States: 1,623,234 (2010)[1] England and Wales: 341,727 (2011)[2] Netherlands: 369,661 (2015)[3] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

|

A Eurasian is a person of mixed Asian and European ancestry. In 19th-century British India, Eurasians – later called Anglo-Indians – were of mixed Portuguese, Dutch, British, Indian or, more rarely, French descent, but now the term is often usually used for parentage from East or Southeast Asia mixed with Europeans .[10] The term has been used in anthropological literature since the 1960s.[11] It may also be extended to those with Central Asian heritage.

Specific groups

Central Asia

Russia, the largest country geographically, is the Eurasian country with the largest Eurasian population, extending into both Asia and Europe. Historically, Central Asia has been a "melting pot" of West Eurasia and East Eurasian peoples, leading to high genetic admixture and diversity.[12] Physical and genetic analyses of ancient remains have concluded that – while the Scythians, including those in the eastern Pazyryk region – possessed predominantly features, found among others, in Europoids, mixed Eurasian phenotypes were also frequently present, suggesting that the Scythians as a whole were descended in part from East Eurasian populations.[13]

Anthropologist SA Pletnev studied a group of burials of Kipchaks in the Volga region and found them to have Caucasoid features with some admixture of Mongoloid traits, with physical characteristics such as flat face and distinctly protruding nose.[14] They were nomadic people that, together with the Cumans, ruled areas stretching from Kazakhstan, Caucasus, eastern Europe. Like the Kipchaks, the Cumans invaders of Europe were also of mixed anthropological origins. Excavation at Hungary Csengele, were far from genetic homogeneity showing both Mongoloid and European traits. Five of the six skeletons that were complete enough for anthropometric analysis and they appeared Asian rather than European (Horváth 1978, 2001)

The Hunnic invaders of Europe were also of mixed origins. Hungarian archaeologist István Bóna argues that most of Europeans Huns were of Caucasoid and that less than 20–25% were of Mongoloid stock.[15] Turanid was most common among the Hun, According to the Hungarian anhtropologist Pál Lipták (1955) the Turanid type is a Caucasoid type with significant Mongoloid admixture, arising from the mixture of the Andronovo type of Europoid features and the Oriental (Mongoloid).[16]

The Eurasian Avars were group of sixth-century nomadic warriors that came from Northern Central Asia who ruled in what is today Central Europe. Anthropological research has revealed few skeletons with Mongoloid-type features, although there was continuing cultural influence from the Eurasian nomadic steppe. The early Avar anthropological material was said to be almost exclusively Europoid in the seventh century according to Pál Lipták, while grave-goods indicated Middle and Central Asian parallels. Mongoloid and Euro-Mongoloid types compose about one-third of the total population of the Avar graves of the eighth century with the late Avar Period showing more hybridization resulting in higher frequencies of Europo-Mongolids.[17] Initially, the Avars and their subjects lived separately, except for Slavic and Germanic women who were married to Avar men. Eventually, the Germanic and Slavic peoples were included in the Avaric social order and culture, which itself was Persian-Byzantine in fashion.[18]

The Seljuk empire which ruled from Central Asia, Middle East to modern Turkey, their descendants are the Iranian Turkmen and Afghan Turkmen and are mixture of Mongoloid/Caucasoid.

Like the Kipchaks, the Cuman invaders of Europe were also of mixed anthropological origins. Excavations in Csengele, Hungary, have revealed normatively East Asian and European traits. Five of the six skeletons that were complete enough for anthropometric analysis appeared Asian rather than European.[19]

Many Eurasian ethnic groups arose during the Mongol invasion of Europe. Partial Mongol descendants of Central Asians and Circassians, such as the Uzbeks, Kazakhs, and Nogais, also created many Eurasian ethnic groups under the empires they established (for example, the Timurid dynasty, Mughal Empire, Kazakh Khanate, and Nogai Horde), which covered vast areas of Russia, the Caucasus, the Middle East, Central Asia, and South Asia. The term Eurasian was first coined in British India in 1844 by the Marquess of Hastings. The term was originally used to refer to those who are now known as Anglo-Indians, people of mixed British and Indian descent.[20]

Southeast Asia

European colonization of vast swathes of Southeast Asia led to the burgeoning of Eurasian populations, particularly in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Timor-Leste, Vietnam and most of all in the Philippines. The majority of Eurasians in Southeast Asia formed a separate community from the indigenous peoples and the European colonizers, and served as middlemen between the two. Post-colonial Eurasians can be found in practically every country in Southeast Asia, most especially in the Philippines due to the 377 years of colonization by Spain, 4 years of British settlement and 49 years of American settlement which gives the country the longest unstopping 426 years of continuously European exposure in Southeast Asia. While Burma was colonized by British for 124 years, the French controlled Indochina for 67 years, the British controlled Malaysia for 120 years and Dutch controlled Indonesia for 149 years after Portugal.

Cambodia

In the last official census in French Indochina in 1946, there were 45,000 Europeans in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. One-fifth were Eurasian.[21]

Jean-François Izzi, a French banker of Italian origin, was the father of the Queen Mother of Cambodia, Norodom Monineath.[22] The son of Norodom Monineath is the reigning King of Cambodia, Norodom Sihamoni.

Indonesia

Studio portrait of an Indo-European family, Dutch East Indies (1890-1910)

Studio portrait of an Indo-European family, Dutch East Indies (1890-1910) Studio portrait of the family Engelenburg Banjoewangi (1919)

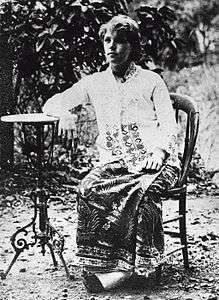

Studio portrait of the family Engelenburg Banjoewangi (1919) Mrs. Mertens in sarong and kabaja, Java (ca. 1888)

Mrs. Mertens in sarong and kabaja, Java (ca. 1888) Dutch Totok father with Indo wife and children (1922)

Dutch Totok father with Indo wife and children (1922) Japanese Indonesian identity card in the name of Johanna Maria Durand Leeuwenburgh

Japanese Indonesian identity card in the name of Johanna Maria Durand Leeuwenburgh Dutch-Indonesian General Gerardus Johannes Berenschot

Dutch-Indonesian General Gerardus Johannes Berenschot Dutch-German-Indonesian National Hero Ernest Douwes Dekker

Dutch-German-Indonesian National Hero Ernest Douwes Dekker Dutch-French-Indonesian National Hero Pierre Tendean

Dutch-French-Indonesian National Hero Pierre Tendean Dutch-Indonesian poet and author Edgar du Perron

Dutch-Indonesian poet and author Edgar du Perron- French-Chinese-Indonesian actress Fifi Young

Dutch-Indonesian novelist Maria Dermoût

Dutch-Indonesian novelist Maria Dermoût- Dutch-Indonesian Defense Minister Juwono Sudarsono

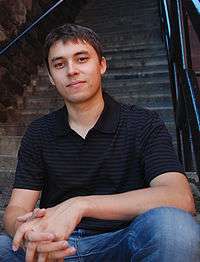

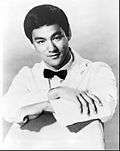

German-Indonesian Actor and tech entrepreneur Christian Sugiono

German-Indonesian Actor and tech entrepreneur Christian Sugiono Austrian-Indonesian actress and singer Sophia Latjuba

Austrian-Indonesian actress and singer Sophia Latjuba- Dutch-Jewish-Indonesian rock musician, songwriter, arranger, and producer Ahmad Dhani

Dutch-Arab-Indonesian Footballer Irfan Bachdim

Dutch-Arab-Indonesian Footballer Irfan Bachdim_crop.jpg) British-Indonesian singer, dancer, actress, model Dewi Sandra

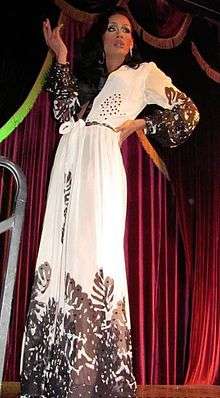

British-Indonesian singer, dancer, actress, model Dewi Sandra Dutch-Indonesian drag performer Sutan Amrull

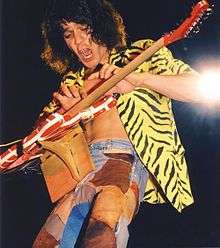

Dutch-Indonesian drag performer Sutan Amrull Dutch-Indonesian musician, songwriter and producer Eddie Van Halen

Dutch-Indonesian musician, songwriter and producer Eddie Van Halen British-Indonesian Barack Obama's half sister Maya Soetoro-Ng

British-Indonesian Barack Obama's half sister Maya Soetoro-Ng

The Eurasian community from Indonesia developed over a splitting periods of 400 years, it began with a mostly Portuguese Indonesian ancestry and ended with a dominant Dutch-Indonesian ancestry after the arrival of the Dutch East India Company in Indonesia in 1603 and near continuous Dutch rule until the Japanese occupation of Indonesia in World War II.

Indo is a term used to describe Europeans, Asians, and Eurasian people who were a migrant population that associated themselves with and experienced the colonial culture of the former Dutch East Indies, a Dutch colony in Southeast Asia that became Indonesia after World War II.[23][24][25][26] It was used to describe people acknowledged to be of mixed Dutch and Indonesian descent, or it was a term used in the Dutch East Indies to apply to Europeans who had partial Asian ancestry.[26][27][28][29][30] The European ancestry of these people was predominantly Dutch, and also Portuguese, British, French, Belgian, German, and others.[31]

Other terms used were Indos, Dutch Indonesians, Eurasians,[32] Indo-Europeans, Indo-Dutch,[26] and Dutch-Indos.[33][34][35][36][37]

Malaysia

There are over 29,000 Eurasians living in Malaysia, the vast majority of whom are of Portuguese descent.[38]

In East Malaysia, the exact number of Eurasians are unknown. Recent DNA studies by Stanford found that 7.8% of samples from Kota Kinabalu have European chromosomes.[39]

Portuguese-Malaysian Indian entrepreneur Tony Fernandes

Portuguese-Malaysian Indian entrepreneur Tony Fernandes Scottish-Malaysian Chinese, Malay and Iban politician Nancy Shukri

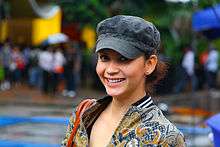

Scottish-Malaysian Chinese, Malay and Iban politician Nancy Shukri American-Malaysian actress Diana Danielle

American-Malaysian actress Diana Danielle Dutch-Javanese-Arab-Malaysian Chinese pop and R&B singer Ning Baizura

Dutch-Javanese-Arab-Malaysian Chinese pop and R&B singer Ning Baizura Swedish-Malaysian Footballer Junior Eldstål

Swedish-Malaysian Footballer Junior Eldstål German-Malaysian Indian/Chinese film actress, television host, and singer Maya Karin

German-Malaysian Indian/Chinese film actress, television host, and singer Maya Karin American-Malaysian actress and model Julia Ziegler

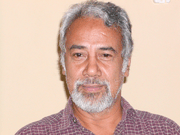

American-Malaysian actress and model Julia Ziegler.jpg) Circassian-Malaysian politician and a Menteri Besar(Chief Minister) of Johore Dato'Onn Jaafar

Circassian-Malaysian politician and a Menteri Besar(Chief Minister) of Johore Dato'Onn Jaafar

Zara Davidson of mixed Arab, English and Malay descent is Perak's current queen consort to Sultan Nazrin Muizzuddin Shah

Zara Davidson of mixed Arab, English and Malay descent is Perak's current queen consort to Sultan Nazrin Muizzuddin Shah- Sultan Ibrahim Ismail of mixed Chinese, Danish, English and Malay descent is the incumbent Sultan of Johor.

French-Malaysian actor and director Pierre Andre

French-Malaysian actor and director Pierre Andre

Myanmar

Philippines

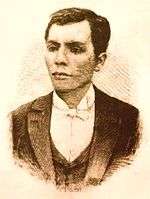

President Manuel L. Quezon

President Manuel L. Quezon

.png)

Eurasians are collectively called Mestizos in the Philippines. The vast majority are descendants of Spanish, Latino and American settlers who intermarried with people of indigenous Filipino and/or Chinese descent. Aside from the more common Spanish, Latino and American mestizos, there are also Eurasians in the Philippines who have ancestries from various European countries or Australia. Significant intermarriage between Filipinos and European Americans has occurred since the United States colonial period up to the present day, as the US had numerous people stationed there at military bases.

Most Eurasians of Spanish or Latino descent own business conglomerates in the real estate, agriculture, and utilities sector, whereas Eurasians of White American descent are largely in the entertainment industry as actors and actresses.

The actual number of Eurasians in the Philippines cannot be ascertained due to lack of surveys, although Spanish censuses record that as much as one third of the inhabitants of the island of Luzon possess varying degrees of Spanish or Latino admixture.

As opposed to the policies of other colonial powers such as the British or the Dutch, the Spanish colonies were devoid of any anti-miscegenation laws. Moreover, the Catholic Church not only never banned interracial marriage, but it even encouraged it. The fluid nature of racial integration in the Philippines during the Spanish colonial period was recorded by many travelers and public figures at the time, who were favorably impressed by the lack of racial discrimination, as compared to the situation in other European colonies.

Among them was Sir John Bowring, Governor General of British Hong Kong and a well-seasoned traveler who had written several books about the different cultures in Asia, who described the situation as "admirable" during a visit to the Philippines in the 1870s.

The lines separating entire classes and races, appeared to me less marked than in the Oriental colonies. I have seen on the same table, Spaniards, Mestizos (Chinos cristianos) and Indios, priests and military. There is no doubt that having one Religion forms great bonding. And more so to the eyes of one that has been observing the repulsion and differences due to race in many parts of Asia. And from one (like myself) who knows that race is the great divider of society, the admirable contrast and exception to racial discrimination so markedly presented by the people of the Philippines is indeed admirable.[40]

Another foreign witness was English engineer, Frederic H. Sawyer, who had spent most of his life in different parts of Asia and lived in Luzon for fourteen years. His impression was that as far as racial integration and harmony was concerned, the situation in the Philippines was not equaled by any other colonial power:

"... Spaniards and natives lived together in great harmony, and do not know where I could find a colony in which Europeans mixes as much socially with the natives.

Not in Java, where a native of position must dismount to salute the humblest Dutchman.

Not in British India, where the Englishwoman has now made the gulf between British and native into a bottomless pit."[41]

In the present times, Filipino mestizos do not socially separate themselves from other Filipinos, making them the only Eurasians to do so. As of today European genes is spread throughout the country in great but specifically unknown scale, together with Chinese Genes and with Indian, Arabic, African, Japanese and Korean genes, that evolved modern Filipinos in a distinctive Austronesian path. In a research done by Dr. Michael Purugganan, NYU Dean of Science in 2013, he concluded that Filipinos today are the conclusion of an Austronesian's evolutionary result of almost 500 years of European(Hispanic/British/Americans) settling with the Natives and other migrant Asians in the Islands.

Singapore

Thailand

Vietnam

In the last official census in French Indochina in 1946, there were 45,000 Europeans in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. One-fifth were Eurasian.[21]

Much of the business conducted with foreign men in Southeast Asia was done by the local women, who served engaged in both sexual and mercantile intercourse with foreign male traders. A Portuguese and Malay speaking Vietnamese woman who lived in Macao for an extensive period of time was the person who interpreted for the first diplomatic meeting between Cochin-China and a Dutch delegation, she served as an interpreter for three decades in the Cochin-China court with an old woman who had been married to three husbands, one Vietnamese and two Portuguese.[42][43][44] The cosmopolitan exchange was facilitated by the marriage of Vietnamese women to Portuguese merchants. Those Vietnamese woman were married to Portuguese men and lived in Macao which was how they became fluent in Malay and Portuguese.[45]

Alexander Hamilton said that "The Tonquiners used to be very desirous of having a brood of Europeans in their country, for which reason the greatest nobles thought it no shame or disgrace to marry their daughters to English and Dutch seamen, for the time they were to stay in Tonquin, and often presented their sons-in-law pretty handsomely at their departure, especially if they left their wives with child; but adultery was dangerous to the husband, for they are well versed in the art of poisoning."[46]

East Asia

China

Hong Kong

In 19th century Hong Kong, Eurasian or "half-caste" children were often stigmatised as symbols of 'moral degradation' and 'racial impurity' by both European and Chinese communities.[47] According to Chiu:

To the European community, such children were the ‘tangible evidence of moral irregularity’, while to the Chinese community they embodied the shame and ‘evil’ of their marginalised mothers. Stewart has commented that, ‘The word "barbarian" on the lip of a Greek contained but an iota of the contempt which the Chinese entertain for such persons’.[47]

In the 1890s Ernst Johann Eitel, a German missionary, controversially claimed that most "half-caste" people in Hong Kong were descended exclusively from Europeans having relationships with outcast groups such as the Tanka people. Carl Smith's study in the 1960s on "protected women" (the kept mistresses of foreigners) to an extent supports Eitel's theory. The Tanka were marginalised in Chinese society which consisted of the majority Puntis (Cantonese-speaking people). Custom precluded their intermarriage with the Cantonese and Hakka-speaking populations and they had limited opportunities of settlement on land. Consequently, the Tanka did not experience the same social pressures when dealing with Europeans. Eitel's theory, however, was criticised by Henry J. Lethbridge writing in the 1970s as a "myth" propagated by xenophobic Cantonese to account for the establishment of the Hong Kong Eurasian community.[48][49][50][51]

Elizabeth Wheeler Andrew (1845–1917) and Katharine Caroline Bushnell (1856–1946) wrote extensively about the position of women in the British Empire. Published in 1907, Heathen Slaves and Christian Rulers, which examined the exploitation of Chinese women in Hong Kong under colonial rule, discussed the Tanka inhabitants of Hong Kong and their position in the prostitution industry, catering towards foreign sailors. The Tanka did not marry with the Chinese, being descendants of the natives, they were restricted to the waterways. They supplied their women as prostitutes to British sailors and assisted the British in their military actions around Hong Kong.[52] The Tanka in Hong Kong were considered as "outcasts".[53] Tanka women were ostracized from the Cantonese community, and were nicknamed "salt water girls" (ham shui mui) for their services as prostitutes to foreigners in Hong Kong.[54][55]

Notable examples of Eurasian people from Hong Kong include Nancy Kwan, once a Hollywood sex symbol, born to a Cantonese father and English and Scottish mother, Bruce Lee, the martial artist icon born to a Cantonese father and a Eurasian mother, and Macao-born actress Isabella Leong, born to a Portuguese-English father and a Chinese mother. The Jewish Dutch man Charles Maurice Bosman[56] was the father of the brothers Sir Robert Hotung and Ho Fook who was the grandfather of Stanley Ho. The number of people who identified as "Mixed with one Chinese parent" according to the 2001 Hong Kong Census was 16,587, which had risen to 24,649 in 2011.[7]

Macau

The early Macanese ethnic group was formed from Portuguese men with Malay, Japanese, Indian women.[57] The Portuguese encouraged Chinese migration to Macau, and most Macanese in Macau were formed from between Portuguese and Chinese. In 1810, the total population of Macau was about 4033, of which 1172 were white men, 1830 were white women, 425 male slaves, and 606 female slaves. In 1830, the population increased to 4480 and the breakdown was 1,202 white men, 2149 white women, 350 male slaves and 779 female slaves. There is reason to speculate that large numbers of white women were involved in some forms of prostitution which would probably explain the abnormality in the ratio between men and women among the white population.[58] Majority of the early Chinese-Portuguese intermarriages were between Portuguese men and women of Tanka origin, who were considered the lowest class of people in China and had relations with Portuguese settlers and sailors, or low class Chinese women.[59][60] Western men like the Portuguese were refused by high class Chinese women, who did not marry foreigners.[61] while a minority were Cantonese men and Portuguese women. Macanese men and women also married with the Portuguese and Chinese, as a result some Macanese became indistinguishable from the Chinese or Portuguese population. Because the majority of the population who migrated to Macau were Cantonese, Macau became a culturally Cantonese-speaking society, other ethnic groups became fluent in Cantonese. Most Macanese had paternal Portuguese heritage until 1974.[59] It was in 1980s that Macanese and Portuguese women began to marry men who defined themselves ethnically as Chinese,[62] which resulted in many Macanese with Cantonese paternal ancestry. Many Chinese became Macanese simply by converting to Catholicism, and had no ancestry from the Portuguese, having assimilated into the Macanese people since they were rejected by non Christian Chinese.[63]

After the handover of Macau to China in 1999 many Macanese migrated to other countries. Of the Portuguese and Macanese women who stayed in Macau married with local Cantonese men, resulting in more Macanese with Cantonese paternal heritage. There are between 25,000-46,000 Macanese; 5,000-8,000 of whom live in Macau, while most live in Latin America (most particularly Brazil), America, and Portugal. Unlike the Macanese of Macau who are strictly of Chinese and Portuguese heritage, many Macanese living abroad are not entirely of Portuguese and Chinese ancestry; many Macanese men and women intermarried with the local population of America and Latin America etc. and have only partial Macanese heritage.

Japan

Amerasian Japanese in Okinawa and Japan are mostly the result of European American soldiers and Japanese women. Including, an estimated Japanese 50,000 women who migrated from Japan to the United States during 1946-1965, as war brides of most white American soldiers.[64] Many Latin Americans in Japan (known in their own cultures as dekasegi) are mixed, including Brazilians of Portuguese, Italian, German, Spaniard, Polish and Ukrainian descent. In Mexico and Argentina, for example, those mixed between nikkei and non-nikkei are called mestizos de japonés, while in Brazil both mestiço de japonês and ainoko, ainoco or even hafu are common terms.

South Korea

U.S. military personnel married 6423 Korean women as war brides during and immediately after the Korean War. The average number of Korean women marrying US military personnel each year was about 1500 per year in the 1960s and 2300 per year in the 1970s.[65] Since the beginning of the Korean War in 1950, nearly 100,000 Korean women have immigrated to the United States as the wives of American soldiers. Based on extensive oral interviews and archival research, Beyond the Shadow of the Camptowns tells the stories of these women, from their presumed association with U.S. military camptowns and prostitution to their struggles within the intercultural families they create in the United States.[66]

Taiwan

During the Siege of Fort Zeelandia in which Chinese Ming loyalist forces commanded by Koxinga besieged and defeated the Dutch East India Company and conquered Taiwan, the Chinese took Dutch women and children prisoner. Koxinga took Hambroek's teenage daughter as a concubine,[67][68][69] and Dutch women were sold to Chinese soldiers to become their wives. In 1684 some of these Dutch wives were still captives of the Chinese.[70]

Some Dutch physical looks like auburn and red hair among people in regions of south Taiwan are a consequence of this episode of Dutch women becoming concubines to the Chinese commanders.[71]

During the 1950-1970s there were numerous US servicemen stationed in Taiwan in various capacities. Some US Vietnam servicemen stayed for R&R and fathered children. Recent years there are many Americans and other nationalities many men married into Taiwanese cultural. In recent years with Taiwan and Central American commerce there are Taiwanese bring back American brides further adding newer blood into Taiwan's population.

South Asia

Bangladesh

There are about 97,000 Anglo Indians in Bangladesh. 55% of them are Christians.[72]

Burma

India

The first use of the term 'Anglo-Indian' was to describe all British people living in India, regardless of whether they had Indian ancestors or not. This usage changed to describe people who were of the very specific lineage descending from the British on the male side and women from the Indian side.[73] People of mixed British and Indian descent were previously referred to as simply 'Eurasians'.[10]

During the British East India Company's rule in India in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, it was initially fairly common for British officers and soldiers to take local Indian wives and have Eurasian children. Many European women were barred from being with native men. Even so, there were still many Indian sepoy men who took European wives. Interracial marriages between European men and Indian women were very common during early colonial times. The scholar Michael Fisher estimates that one in three European men during the company rule p had Indian wives. The Europeans (mostly Portuguese, Dutch, French, German, Irish, Scottish, and English) were stationed in India in their youth, and looked for relationships with local women.[74][75] The most famous of such interracial liaisons was between the Hyderabadi noblewoman Khair-un-Nissa and the Scottish resident James Achilles Kirkpatrick. In addition to intermarriage, inter-ethnic prostitution in India existed. Generally, Muslim women did not marry European men because the men were not of the Islamic faith. By the mid-nineteenth century, there were around 40,000 British soldiers but fewer than 2000 British officials present in India.[76] As British women began arriving to India in large numbers around the early-to-mid-nineteenth century, mostly as family members of British officers and soldiers, intermarriage with Indians became less frequent among the British in India. After the events of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, such intermarriage was considered undesirable by both cultures.[77] The colonial government passed several anti-miscegenation laws.[78][79] As a result, Eurasians became more marginal to both the British and Indian populations in India.

Over generations, Anglo-Indians intermarried with other Anglo-Indians to form a community that developed a culture of its own. They created distinctive Anglo-Indian, dress, speech and religion. They established a school system focused on English language and culture, and formed social clubs and associations to run functions, such as regular dances, at holidays such as Christmas and Easter.[73] Over time, the British colonial government recruited Anglo-Indians into the Customs and Excise, Post and Telegraphs, Forestry Department, the Railways and teaching professions, but they were employed in many other fields as well. A number of factors fostered a strong sense of community among Anglo-Indians. Their English-language school system, their Anglocentric culture, and their Christian beliefs helped bind them together.[80] Today, an estimated 300,000-1 million Anglo-Indians live in India.[81]

Sri Lanka

Due to prolonged colonial contact with Portugal, the Netherlands and Britain, Sri Lanka has had a long history of intermarriage between locals and colonists. Originally these people were known as Mestiços, literally "mixed people" in Portuguese; today they are collectively classified as Burghers. The Sri Lankan Civil War prompted numerous Burghers to flee the island. Most of them settled in Europe, the Americas, Australia and New Zealand.

Portuguese Burghers are usually descended from a Sri Lankan mother and a Portuguese father, or a Sri Lankan mother of Portuguese descent and a Sri Lankan father (the former is more common).[82] This configuration is also the case with the Dutch Burghers. When the Portuguese arrived on the island in 1505, they were accompanied by African slaves. Kaffirs are a mix of African, Portuguese colonist and Sri Lankan. The free mixing between the various groups of people was encouraged by the colonials. Soon the Mestiços or the "Mixed People" began speaking a creole known as the Ceylonese-Portuguese Creole. It was based on Portuguese, Sinhalese and Tamil.

The Burgher population numbers 40,000 in Sri Lanka and thousands more worldwide, concentrated mostly in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Phenotypically Burghers can have skin ranging from light to darker, depending on their ancestors, even within the same family. Burghers with dark to light brown skin usually are of Portuguese Burghers or Kaffir ancestry; they may also have European facial features common to the Mediterranean basin (see Mediterraneans). They have a distinct look compared to native Sri Lankans. Most light-skinned Burghers are of Dutch or British descent. Most Burghers are Roman Catholic in religion.

The long and rich colonial past of Sri Lanka left lasting impressions on the cultures and the languages of the island. Both Sinhalaese and Sri Lankan (Ceylonese) Tamil contain numerous words from Portuguese, Dutch and English.

Like certain other Asian countries -Japan, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore and the Philippines- Eurasians/Burghers have also been sought after by advertisers and modelling agencies in Sri Lanka. Their mixed look combining both Western and Sri Lankan features makes them attractive to advertisers who see them as a representation of an "exotic Sri Lankan/Sinhalese". Predictions within the advertising industry in Sri Lanka estimate that more than 50% of advertising models in Sri Lanka are Burghers/Eurasians.[83]

Europe

Colonization of Europe has led to the rise of Eurasian communities in Europe, most prominently in the Netherlands, Spain, and United Kingdom, where significant numbers of Indonesian, Filipino, and Indo-Pakistani Eurasians live. Turkish Empire spanned large parts of Europe and gave rise to populations with mixed ancestry in their former territories. The Red Army's march to Europe resulted in large scale atrocities against German women that most likely resulted in subsequent population of Germany having large minority with mixed ethnicity.[84]

Netherlands

Dutch Eurasians of part Indonesian descent, also called Indos or Indo-Europeans, have largely assimilated in the Netherlands [85] arriving in the Netherlands following the end of World War II until 1965, their diaspora a result of Indonesia gaining its independence from Dutch colonial rule. Statistics show high inter marriage rates with native Dutch (50-80%). With over 500,000 persons, they are the largest ethnic minority in the Netherlands. So-called Indo rockers such as the Tielman Brothers introduced their blend of rock and roll music to Dutch audiences, whereas others gained fame as singers and TV presenters, such as Rob de Nijs and Sandra Reemer. There are also famous Indo soccer players such as Giovanni van Bronckhorst and Robin van Persie. Well-known politicians, such as Christian democrat Hans van den Broek and politician Geert Wilders, are also of Indo descent.

Spain

Spanish Eurasians, called Mestizos, most of whom are of partial Filipino ancestry, make up a small but important minority in Spain. Numbering about 115,000, they consist of early migrants to Spain after the loss of the Philippines to the United States in 1898.

Well known Spanish Eurasians include actress and socialite Isabel Preysler and her son Enrique Iglesias, as well as former Prime Minister Marcelo Azcarraga Palmero.

Spain a large population of mixed ethnicity due to colonization by Islamic armies from Asia.

United Kingdom

Interracial marriage was fairly common in Britain since the seventeenth century, when the British East India Company began bringing over thousands of Indian scholars, lascars and workers (mostly Bengali and/or Muslim) to Britain. Most married and cohabited with local white British women and girls, due to the absence of Indian women in Britain at the time. This later became an issue, as a magistrate of the London Tower Hamlets area in 1817 expressed disgust at how the local British women and girls in the area were marrying and cohabiting with foreign South Asian lascars. Nevertheless, there were no legal restrictions against 'mixed' marriages in Britain, unlike the restrictions in India.[86][87][88] This led to "mixed race" Eurasian (Anglo-Indian) children in Britain, which challenged the British elite efforts to "define them using simple dichotomies of British versus Indian, ruler versus ruled." By the mid-nineteenth century, there were more than 40,000 Indian seamen, diplomats, scholars, soldiers, officials, tourists, businessmen and students arriving in Britain,[74] and by the time World War I began, there were 51,616 Indian lascar seamen residing in Britain.[89] In addition, the British officers and soldiers who had Indian wives and Eurasian children in British India often brought them to Britain in the nineteenth century.[90]

Following World War I, there were more women than men in Britain,[91] and there were increasing numbers of seamen arriving from abroad, mostly from the Indian subcontinent, in addition to smaller numbers from Yemen, Malaysia and China. This led to increased intermarriage and cohabitation with local white females. Some residents grew concerned about miscegenation and there were several race riots at the time.[92] In the 1920s to 1940s, several writers raised concerns about an increasing 'mixed-breed' population, born mainly from Muslim Asian (mostly South Asian in addition to Arab and Malaysian) fathers and local white mothers, occasionally out of wedlock. They denounced white girls who mixed with Muslim Asian men as 'shameless' and called for a ban on the breeding of 'half-caste' children. Such attempts at imposing anti-miscegenation laws were unsuccessful.[93] As South Asian women began arriving in Britain in large numbers from the 1970s, mostly as family members, intermarriage rates have decreased in the British Asian community, although the size of the community has increased. As of 2006, there are 246,400 'British Mixed-Race' people of European and South Asian descent. There is also a small Eurasian community in Liverpool. The first Chinese settlers were mainly Cantonese from south China some were also from Shanghai. The figures of Chinese for 1921 are 2157 men and 262 women. Many Chinese men married British women while others remained single, possibly supporting a wife and family back home in China. During World War II (1939-1945) another wave of Chinese seamen from Shanghai and of Cantonese origin married British women. Records show that about some 300 of these men had married British women and supported families.[94]

North America

Cuba

There were almost no women among the nearly entirely male Chinese coolie population that migrated to Cuba.[95][96] In Cuba some Indian (Native American), mulatto, black, and white women engaged in carnal relations or marriages with Chinese men, with marriages of mulatto, black, and white woman being reported by the Cuba Commission Report.[97]

120,000 Cantonese 'coolies' (all males) entered Cuba under contract for 80 years. Most of these men did not marry, but Hung Hui (1975:80) cites there was a frequency of sexual activity between black women and these Asian immigrants. According to Osberg (1965:69) the free Chinese practice of buying slave women and then freeing them expressly for marriage was utilized at length. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Chinese men (Cantonese) engaged in sexual activity with black Cuban women, and from such relations many children were born. (For a British Caribbean model of Chinese cultural retention through procreation with black women, see Patterson, 322-31).[98]

In the 1920s an additional 30,000 Cantonese and small groups of Japanese also arrived; both immigrations were exclusively male, and there was rapid intermarriage with white, black, and mulato populations.[99][100] CIA World Factbook. Cuba. 2008. May 15, 2008. claimed 114,240 Chinese-Cuban coolies with only 300 pure Chinese.[101]

In the study of genetic origin, admixture, and asymmetry in maternal and paternal human lineages in Cuba. Thirty-five Y-chromosome SNPs were typed in the 132 male individuals of the Cuban sample. The study does not include any people with some Chinese ancestry. All the samples were white Cubans and black Cubans. Two out of 132 male sample belong to East Asian Haplogroup O2 which is found in significant frequencies among Cantonese people is found in 1.5% of Cuban population.[102]

Costa Rica

The Chinese originated from the Cantonese male migrants. Pure Chinese make up only 1% of the Costa Rican population but according to Jacqueline M. Newman close to 10% of Costa Ricans are of Chinese descent or married to a Chinese.[103] Most Chinese immigrants since then have been Cantonese, but in the last decades of the twentieth century, a number of immigrants have also come from Taiwan. Many men came alone to work and married Costa Rican women and speak Cantonese. However the majority of the descendants of the first Chinese immigrants no longer speak Cantonese and feel themselves to be Costa Ricans.[104] They married Tican women (who are a blend of Europeans, Caztizos, Mestizos, Indian, black).[105] A Tican is also a white person with a small portion of nonwhite blood like caztizos. The census In 1989 shows about 98% of Costa Ricans were either white, castizos, mestizos, with 80% being white or caztizos.

Mexico

A marriage between a Chinese man and a white Mexican woman was recorded in "Current anthropological literature, Volumes 1-2", published in 1912, titled "Note on two children born to a Chinese and a Mexican white"- "Note sur deux enfants nes d'un chinois et d une mexicaine de race blanche. (Ibid., 122-125, portr.) Treats briefly of Chen Tean (of Hong Kong), his wife, Inez Mancha (a white Mexican), married in 1907, and their children, a boy (b. April 14, 1908) and a girl (b. Sept. 24, 1909). The boy is of marked Chinese type, the girl much more European. No Mongolian spots were noticed at birth. Both children were born with red cheeks. Neither has ever been sick. The boy began to walk at ten months, the girl a little after a year."[106][107][108][109][110]

Mexican women and Chinese men initiated free unions with each other as recorded by the Chihuahua and Sonora census records, a number Chinese men and their Mexican wives and children came to China to live there while a big amount of Chinese-Mexican families were entirely expelled from northern Mexico to China, during the early 1930s 500 Chinese-Mexican families, numbering around 2,000 people in total came to China, with a large amount of them settling in Portuguese Macau and forming their own ghetto there since they were drawn to the Catholic and Iberian culture of Macau.[111] A lot of couples ended up divorcing in China due to a huge variety of factors which caused stress like culture, economic, and familial with the men leaving Macau with hundreds of Mexican women and mixed children alone. Mexican women in Macau rearing their mixed Chinese children wanted to return to Mexico saying "Even if we have to scrape bittersweet potatoes in the sierra, we want Mexico." and Mexico under President Lázaro Cardenas allowed over 400 Mexican women and their children to come back in 1937-1938 after the women petitioned, after World War II, some Chinese Mexican families also came back and after a petition by mixed race Chinese-Mexicans who had been deported from Mexico and raised in Macau led another campaign to allow them to return home in 1960.[112] Children which were born to Mexican women and sired by Chinese men were counted as ethnic Chinese by Mexican census takers since they were not considered Mexicans by the general public and viewed as Chinese.[113] The Mexican ideology of mestizaje portrayed the quintessential Mexican identity as being made from a mix of indigenous native and Spanish white, with Mexico being portrayed by racial ideologues as being made out of a south populated by indigenous natives, a central part populated by mixed white-native Mestizos, and a north populated by white Spanish creoles, Sonora was where these white Spanish creoles lived, and the marriage of Chinese with Mexicans was portrayed as particularly threatening to the white identity of Sonora and to the concept of mixed mestizaje identity of indigenous natives and Spanish since the Chinese-Mexican mixed children did not fit into this identity.[114]

The anti-Chinese campaigns resulted in an exodus of Chinese leaving northern Mexican states like Sonora, Sinaloa, Coahuila, Chihuahua and Mexicali, with the Chinese and their families being stripped of the property they took with them as they were forced across the Mexican border into America, where they would be sent back to China, Dr. David Trembly MacDougal said "many of these departing Chinese have married Mexican women, some of whom with their children accompany them into exile.", and after "a lifetime of skillful and honest work" they were driven into poverty by the loss of their property.[115]

Mexico's international image was being damaged by the anti-Chinese expulsion campaign and while attempts were made to reign in anti-Chinese measures by the Mexican federal government, using the war between Japan and China as a reason to stop deporting Chinese, Mexican states continued in the anti-Chinese campaign to drive Chinese out of states like Sinora and Sinaloa with citizenship being stripped from Mexican women who were married to Chinese men, labeled as "race traitors" and from the United States, Sinaloa, and Sonora, both Mexican women, their Chinese husbands and their mixed children were expelled to China [116]

There was a more widespread general anti-foreign sentiment sweeping through Mexico which was against Arabs, eastern Europeans, and Jews, in addition to Chinese, with the anti-Chinese movement being part of this bigger campaign, a Mexican anti-foreign pamphlet exhorted Mexicans to "not spend one penny on the Chinese, Russians, Poles, Czechoslovacs, Lithuanians, Greeks, Jews, Sirio-Lebanese, etc." a poster advocated "boycott sabotage, and expulsion from the country of all foreigners in general, considered as pernicious and undesirable." and warned against Chinese men marrying Mexican women, saying "WHATEVER IT COSTS, MEXICAN WOMAN! Do not fall asleep, help your racial brothers boycott the undesirable foreigners, who steal the bread from our children."[117]

Many Chinese migrated into Sinaloa and into cities such as Mazatlán up to the 1920s where they engaged in business and married Mexican women, this led to the expulsion of Chinese in the 1930s and Sinaloa passed laws expelling the Chinese in 1933, leading to the break up of mixed Chinese Mexican families and Mexican women to be deported to China with their Chinese husbands.[118]

After several hundred Chinese men and their mixed families of Mexican wives and Mexican Chinese children were expelled from Mexico into the United States, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) took charge of these people, took their testimonies and labelled them as refugees before sending them to China, the U.S. immigration employees also included under the category "Chinese refugees from Mexico", the Mexican women and mixed Chinese Mexican children who accompanied the Chinese men and sent them all to China instead of sending the mixed children and Mexican women to Mexico in spite of it having been cheaper, since at this era of history laws and convention regarding citizenship held that women were controlled by their husbands and when they married foreign men, women had their citizenship stripped from them so the women were dealt with by their husbands' standing and conditions so while Chinese men had their testimonies collected, the Mexican women were not interviewed by U.S. immigration officials, and the Mexican women and the mixed Chinese Mexican families were sent to China, even Mexican women who were not officially married but were engaged in relationships with Chinese men. Sinaloa and Sonora saw most of their Chinese population and mixed Chinese Mexican families deported due to the virulent anti-Chinese movement.[119]

The anti-Chinese sentiment in Mexico was spurred on by the onset of the Great Depression, Chinese started to come to Mexico in the late 19th century and the majority of them were in trade and owners of businesses when the Maderistas came into power, marrying Mexican women and siring mixed race children with them which resulted in a law banning Chinese-Mexican marriages in 1923 in Sonora and another law forcing Chinese into ghettos two years after, and in Sinaloa, Sonora, and Chihuahua, the Chinese were driven out in the early 1930s with northern Mexico seeing 11,000 Chinese expelled in total.[120]

The maternal grandfather of Mexican singer Ana Gabriel was a Chinese man named Yang Quing Yong Chizon who adopted the name Roberto in Mexico.

United States

According to the United States Census Bureau, concerning multi-racial families in 1990:[121]

In the United States, census data indicate that the number of children in interracial families grew from less than one half million in 1970 to about two million in 1990. In 1990, for interracial families with one white American partner, the other parent...was Asian American for 45 percent...

According to James P. Allen and Eugene Turner from California State University, Northridge, by some calculations, the largest part-European bi-racial population is European/Native American and Alaskan Native, at 7,015,017; followed by European/African at 737,492; then European/Asian at 727,197; and finally European/Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander at 125,628.[122]

The U.S. Census has categorized Eurasian responses in the "Some other race" section as belonging to the Asian category.[123] The Eurasian responses the US Census officially recognizes are Indo-European, Amerasian, and Eurasian.[123] Starting with the 2000 Census, people have been allowed to mark more than one "race" on the U.S. census, and many have identified as both Asian and European. Defining Eurasians as those who were marked as both "white" and "Asian" in the census, there were 868,395 Eurasians in the United States in 2000 and 1,623,234 in 2010.[4]

Accusations of support for miscegenation were commonly made by slavery defenders against abolitionists before the US Civil War. After the War, similar charges were used by white segregationists against advocates of equal rights for African Americans. They were said to be secretly plotting the destruction of the white race through miscegenation. In the 1950s, segregationists alleged a Communist plot funded by the Soviet Union with that goal. In 1957, segregationists cite the anti-semitic hoax A Racial Program for the Twentieth Century as evidence for these claims.

From the nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, the Chinese who migrated to the United States were almost entirely of Cantonese origin. Anti-miscegenation laws in many states prohibited Chinese men from marrying white women.[124] In the mid-1850s, 70 to 150 Chinese were living in New York City, and 11 of them married Irish women. In 1906 the New York Times (August 6) reported that 300 white women (Irish American) were married to Chinese men in New York, with many more cohabited. In 1900, based on Liang research, of the 120,000 men in more than 20 Chinese communities in the United States, he estimated that one out of every 20 Chinese men (Cantonese) was married to white women.[125] In the 1960s census showed 3500 Chinese men married to white women and 2900 Chinese women married to white men.[126]

Twenty-five percent of married Asian American women have Caucasian spouses, but 45% of cohabitating Asian American women are with Caucasian American men. Of cohabiting Asian men, slightly over 37% of Asian men have white female partners and over 10% married to white women.[127] Asian American women and Asian American men live with a white partner, 40% and 27%, respectively (Le, 2006b). In 2008, of new marriages including an Asian man, 80% were to an Asian spouse and 14% to a white spouse; of new marriages involving an Asian woman, 61% were to an Asian spouse and 31% to a white spouse.[128]

Hawaii

The majority of early Hawaiian Chinese were Cantonese-speaking migrants from Guangdong, with a small number of Hakka speakers. If all people with Chinese ancestry in Hawaii (including the Sino-Hawaiians) are included, they form about one-third of Hawaii's entire population. Many thousands of them married women of Hawaiian, Hawaiian/European and European origin. A large percentage of the Chinese men married Hawaiian and Hawaiian European women. While a minority married white women in Hawaii were with Portuguese women. The 12,592 Asiatic Hawaiians enumerated in 1930 were the result of Chinese men intermarrying with Hawaiian and part Hawaiian European. Most Asiatic Hawaiians men also married Hawaiians and European women (and vice versa). On the census some Chinese with little native blood would be classified as Chinese not an Asiatic Hawaiians due to dilution of native blood. Intermarriage started to decline in the 1920s.[129][130][131] Portuguese and other Caucasian women married Chinese men.[132][133] These unions between Chinese men and Portuguese women resulted in children of mixed Chinese Portuguese parentage, called Chinese-Portuguese. For two years to June 30, 1933, 38 of these children were born, they were classified as pure Chinese because their fathers were Chinese.[134] A large amount of mingling took place between Chinese and Portuguese, Chinese men married Portuguese, Spanish, Hawaiian, Caucasian-Hawaiian, etc.[135][136][137][138] Only one Chinese man was recorded marrying an American woman.[139][140] Chinese men in Hawaii also married Puerto Rican, Portuguese, Japanese, Greek, and half-white women.[141][142]

Oceania

Australia

Most of the early Australian Chinese population consisted of Cantonese-speaking migrants from Guangzhou and Taishan as well as some from Fujian. They migrated to Australia during the gold rush period of the 1850s. Marriage records show that between the 1850s and the start of the twentieth century, there were about 2000 legal marriages between white women and migrant Chinese men in Australia's eastern colonies, probably with similar numbers involved in de facto relationships of various kinds.[143]

A Chinese man Sun San Lung and his son by his white European Australian wife Lizzie in Castlemaine returned to China in 1887 for a trip after marrying a second white wife after Lizzie died, but they were blocked from coming back to Melbourne, Australia. Chinese men were found living with 73 opium addicted Australian white women when Quong Tart surveyed the goldfields for opium addicts, and a lot of homeless women abused by husbands and prostitutes ran away and married Chinese men in Sydney after taking refuge in Chinese opium dens in gambling houses, Reverend Francis Hopkins said that 'A Chinaman's Anglo-Saxon wife is almost his God, a European's is his slave. This is the reason why so many girls transfer their affections to the almond-eyed Celestials.' when giving the reason why these women married Chinese men.[144] After the gold mining ended some Chinese remained in Australia and started families, one youthful Englishwoman married a Chinese in 1870 in Bendigo and the Golden Dragon Museum is run by his great-grandson Russell Jack.[145]

The Australian sniper Billy Sing was the son of a Chinese father and an English mother.[146][147][148][149] His parents were John Sing (c. 1842–1921), a drover from Shanghai, China, and Mary Ann Sing (née Pugh; c. 1857–unknown), a nurse from Kingswinford, Staffordshire, England.[150][151]

The rate of intermarriage declined as stories of the viciousness of Chinese men towards white women spread, mixed with increasing opposition to intermarriage. Rallies against Chinese men taking white women as wives became widespread as many white Australian men saw the intermarriage and cohabitation of Chinese men with white women as a threat to the white race. In late 1878, there were 181 marriages between women of European descent and Chinese men as well as 171 such couples cohabiting without matrimony, resulting in the birth of 586 children of Sino-European descent.[152] Such a rate of intermarriage between Chinese Australians and white Australians was to continue until the 1930s.

South America

Argentina

Today, there are an estimated of 180,000 Asian-Argentines, with 120,000 of Chinese descent,[153] 32,000 of Japanese descent, 25,000 of Korean descent.[154]

Brazil

Common estimates generally include about 25–35% of Japanese Brazilians as multiracial, being generally over 50–60% among the yonsei, or fourth-generation outside Japan. In Brazil, home to the largest Japanese community overseas, miscegenation is celebrated, and it promoted racial integration and mixing over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, nevertheless as a way of dealing with and assimilating its non-white population, submitted to white elites, with no dangers of uprisings that would put its status quo in risk. While culture shock was strong for the first and second generations of Japanese Brazilians, and the living conditions in the fazendas (plantation farms) after the slavery crisis were sometimes worse than in Asia, Brazil stimulated immigration as means of substitution for the lost workforce, and any qualms about the non-whiteness of the Japanese were quickly forgotten. After Japan became one of the world's most developed and rich nations, the Japanese in Brazil and their culture as well gained an image of progress, instead of the old bad perception of a people which would not be assimilated or integrated as its culture and race were deemed as diametrically opposed to the Brazilian ones.

In the censuses, self-reported amarelos (literally "yellows" i.e. Mongolics, people racially Asian) include about 2,100,000 people, or around 1% of the Brazilian population. A greater number of persons may have Japanese and less commonly Chinese and Korean ancestry, but identify as white (Brazilian society has no one drop rule), pardo (i.e. brown-skinned multiracial or assimilated Amerindian, pardo stands for a Brazilian darker than white and lighter than black, but not necessarily implying a white-black admixture) or Afro-Brazilian. When it comes to religion, self-reported Asian Brazilians are only less Irreligious than whites, and a little more Catholic than Amerindians. They are the least group when it comes to traditional churches of Christianity, and also the least group in percent of Protestants, and Evangelicals or Pentecostals as well. Asian Brazilians have the highest income per capita according to the 2010 census.

Peru

About 100,000 Cantonese coolies (almost all males) in 1849 to 1874 migrated to Peru and intermarried with Peruvian women of mestizo, European, Ameridian, European/mestizo, African and mulatto origin. Many Peruvian Chinese and Peruvian Japanese today are of Spanish, Italian, African and Ameridian. Estimates for Chinese-Peruvian is about 1.3-1.6 millions. Asian Peruvians are estimated to be 3% of the population, but one source places the number of citizens with some Chinese ancestry at 4.2 million, which equates to 15% of the country's total population. In Peru non-Chinese women married the mostly male Chinese coolies.[155]

There were almost no women among the nearly entirely male Chinese coolie population that migrated to Peru and Cuba.[156][157] Peruvian women were married to these Chinese male migrants.[158][159][160][161][162] African women particularly had mostly no intercourse with Chinese men during their labor as coolies, while Chinese had contact with Peruvian women in cities, there they formed relationships and sired mixed babies, these women originated from Andean and coastal areas and did not originally come from the cities, in the haciendas on the coast in rural areas, native young women of indígenas (native) and serranas (mountain) origin from the Andes mountains would come down to work, these Andean native women were favored as marital partners by Chinese men over Africans, with matchmakers arranging for communal marriages of Chinese men to indígenas and serranas young women.[163] There was a racist reaction by Peruvians to the marriages of Peruvian women and Chinese men.[164] When native Peruvian women (cholas et natives, Indias, indígenas) and Chinese men had mixed children, the children were called injerto and once these injertos emerged, Chinese men then sought out girls of injertas origins as marriage partners, children born to black mothers were not called injertos.[165] Low class Peurvians established sexual unions or marriages with the Chinese men and some black and Indian women "bred" with the Chinese according to Alfredo Sachettí, who claimed the mixing was causing the Chinese to suffer from "progressive degeneration", in Casa Grande highland Indian women and Chinese men participated in communal "mass marriages" with each other, arranged when highland women were brought by a Chinese matchmaker after receiving a down payment.[166][167] Many Peruvian women were married by Chinese.[168][169] Around the La Concepción market in Lima native Peruvian women cohabited with Chinese male businessmen and artisans.[170] A lot of Peruvian women married Chinese men and raised families with them due to the low number of Chinese women in Peru, one Peruvian woman named Maria Salas married a Chinese man named Manuel Cheon because she viewed Chinese men as more caring since her mother Juana Aldecoa Arrospide de Salas was beaten by her spouse who was Peruvian, and she turned out to be right.[171] There was a disparity between the mixed and the all Chinese couples, in one year a census counted that Chinese men sired 268 children with Peruvian women while all Chinese families sired 79 children.[172] Ecuadorian and Peruvian Chinese families settled in Hong Kong and Macau, in the beginning of the 20th century Peruvian women and their Chinese children who lived in China were allowed to repatriate from China to Peru but Ecuadorian origin families received no help from their government.[173]

In Peru and Cuba some Indian (Native American), mulatto, black, and white women engaged in carnal relations or marriages with Chinese men, with marriages of mulatto, black, and white woman being reported by the Cuba Commission Report and in Peru it was reported by the New York Times that Peruvian black and Indian (Native) women married Chinese men to their own advantage and to the disadvantage of the men since they dominated and "subjugated" the Chinese men despite the fact that the labor contract was annulled by the marriage, reversing the roles in marriage with the Peruvian woman holding marital power, ruling the family and making the Chinese men slavish, docile, "servile", "submissive" and "feminine" and commanding them around, reporting that "Now and then...he [the Chinese man] becomes enamored of the charms of some sombre-hued chola (Native Indian and mestiza woman) or samba (mixed black woman), and is converted and joins the Church, so that may enter the bonds of wedlock with the dusky señorita."[174] Chinese men were sought out as husbands and considered a "catch" by the "dusky damsels" (Peruvian women) because they were viewed as a "model husband, hard-working, affectionate, faithful and obedient" and "handy to have in the house", the Peruvian women became the "better half" instead of the "weaker vessel" and would command their Chinese husbands "around in fine style" instead of treating them equally, while the labor contract of the Chinese coolie would be nullified by the marriage, the Peruvian wife viewed the nullification merely as the previous "master" handing over authority over the Chinese man to her as she became his "mistress", keeping him in "servitude" to her, speedily ending any complaints and suppositions by the Chinese men that they would have any power in the marriage.[175]

References

- 1 2 http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-05.pdf[]

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-02-24. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ↑ http://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/publication/?DM=SLNL&PA=37325&D1=0&D2=a&D3=0&D4=0&D5=a&D6=l&HDR=G2,G3&STB=G1,G5,T,G4&VW=T

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". Factfinder2.census.gov. Retrieved 2014-01-02. Defining Eurasians as those who were marked as both "white" and "Asian", in the 2010 census there were 1,623,234 Eurasians in the United States.

- ↑ http://www.cbs.nl/NR/rdonlyres/482F9147-4512-4E9F-B8EF-BDD3E50607E9/0/2003k1b15p058art.pdf

- ↑ Jarnagin, Laura (2012). Portuguese and Luso-Asian Legacies in Southeast Asia, 1511-2011: Culture and identity in the Luso-Asian world, tenacities & plasticities. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 268. "Today, there are over twenty-nine thousand Eurasians living in Malaysia, the vast majority of whom are of Portuguese descent."

- 1 2 Hong Kong Government. "Ethnic Minorities by Ethnicity and Age Group, 2001, 2006 and 2011 (F401)". Retrieved 5 February 2014. 24,649 people identified as "Mixed with one Chinese parent", according to the 2011 Hong Kong Census.

- ↑ "Culture & identity take centre stage at Eurasian dialogue". Channel NewsAsia. XinMSN. 23 Feb 2013. Retrieved 24 Dec 2013. "There are close to 18,000 Eurasians in Singapore".

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=9yuGDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA123&lpg=PA123&dq=eurasians+in+MAcau&source=bl&ots=GvR8Msjk3X&sig=EEdmylsGzA5TXPbc8xgIJim4hyA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiUnIfZkdzNAhUGp5QKHeYmBXgQ6AEIXjAM#v=onepage&q=eurasians%20in%20MAcau&f=false

- 1 2 "Eurasian". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2009-01-13.

- ↑ Current Anthropology, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Feb., 1961), p. 64.

- ↑ González-Ruiz, Mercedes; Santos, Cristina; Jordana, Xavier; Simón, Marc; Lalueza-Fox, Carles; Gigli, Elena; Pilar Aluja, Maria; Malgosa, Assumpció (2012). "Tracing the Origin of the East-West Population Admixture in the Altai Region (Central Asia)". PLOS ONE. Public Library of Science. 7 (11): 1. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048904. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ↑ An Ancient Scytho-Siberian Pair with Asian Ties Archived October 15, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ SA Pletnev. "Google Translate" (PDF). p. 2.

- ↑ Bóna, István: "A Nagyrév-kultúra településeiről", 1991, p.30. In: Hyun Jin Kim, "The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe Archived August 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.", Cambridge University Press, p.187

- ↑ Lipták, Pál. Recherches anthropologiques sur les ossements avares des environs d'Üllö Archived April 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. (1955) - In: Acta archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, vol. 6 (1955), pp. 231-314

- ↑ "Acta archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae", Magyar Tudományos Akadémia, 1 Jan 1967, Page 86 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-05-07. Retrieved 2015-10-11.

- ↑ History of Transylvania

- ↑

Bogacsi-Szabo, Erika; Kalmar, Tibor; Csanyi, Bernadett; Tomory, Gyongyver; Czibula, Agnes; Priskin, Katalin; Horvath, Ferenc; Downes, Christopher Stephen; Rasko, Istvan (October 2005). "Mitochondrial DNA of Ancient Cumanians: Culturally Asian Steppe Nomadic Immigrants with Substantially More Western Eurasian Mitochondrial DNA Lineages". Human Biology. Detroit, MI, USA: Wayne State University Press. 77 (5): 639–662. doi:10.1353/hub.2006.0007. ISSN 0018-7143. LCCN 31029123. OCLC 1752384. PMID 16596944. Retrieved 2014-03-01. (subscription required (help)).

Bogacsi-Szabo, Erika; Kalmar, Tibor; Csanyi, Bernadett; Tomory, Gyongyver; Czibula, Agnes; Priskin, Katalin; Horvath, Ferenc; Downes, Christopher Stephen; Rasko, Istvan (October 2005). "Mitochondrial DNA of Ancient Cumanians: Culturally Asian Steppe Nomadic Immigrants with Substantially More Western Eurasian Mitochondrial DNA Lineages". Human Biology. Detroit, MI, USA: Wayne State University Press. 77 (5): 639–662. doi:10.1353/hub.2006.0007. ISSN 0018-7143. LCCN 31029123. OCLC 1752384. PMID 16596944. Retrieved 2014-03-01. (subscription required (help)). - ↑ Meiqi Lee (2004). Being Eurasian: Memories Across Racial Divides (illustrated ed.). Hong Kong University Press. p. 2. ISBN 962-209-671-9. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

- 1 2 Thomas A. Bass. Vietnamerica: The War Comes Home. New York: Soho Press, 1996, p. 86

- ↑ The Royal House of Cambodia, Julio A. Jeldres, Monument Books, 2003, p. 69

- ↑ van Amersfoort, H. (1982). "Immigration and the formation of minority groups: the Dutch experience 1945-1975". Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Sjaardema, H. (1946). "One View on the Position of the Eurasian in Indonesian Society". The Journal of Asian Studies. 5: 172–175. doi:10.2307/2049742.

- ↑ Bosma, U. (2012). Post-colonial Immigrants and Identity Formations in the Netherlands. Amsterdam University Press. p. 198.

- 1 2 3 van Imhoff, E.; Beets, G. (2004). "A demographic history of the Indo-Dutch population, 1930–2001". Journal of Population Research. Springer. 21 (1): 47–49. doi:10.1007/bf03032210. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ Lai, Selena (2002). Understanding Indonesia in the 21st Century. Stanford University Institute for International Studies. p. 12.

- ↑ J. Errington, Linguistics in a Colonial World: A Story of Language, 2008, Wiley-Blackwell, p. 138

- ↑ The Colonial Review. Department of Education in Tropical Areas, University of London, Institute of Education. 1941. p. 72.

- ↑ Bosma, U.; Raben, R. (2008). Being "Dutch" in the Indies: a history of creolisation and empire, 1500–1920. University of Michigan, NUS Press. pp. 21,37,220. ISBN 9971-69-373-9. Indos–people of Dutch descent who stayed in the new republic Indonesia after it gained independence, or who emigrated to Indonesia after 1949–are called Dutch-Indonesians. Although the majority of the Indos are found in the lowest strata of European society, they do not represent a solid social or economic group."

- ↑ van der Veur, P. (1968). "The Eurasians of Indonesia: A Problem and Challenge in Colonial History". Journal of Southeast Asian History. 9: 191. doi:10.1017/s021778110000466x.

- ↑ Knight, G. (2012). "East of the Cape in 1832: The Old Indies World, Empire Families and "Colonial Women" in Nineteenth-century Java". Itinerario. 36: 22–48. doi:10.1017/s0165115312000356.

- ↑ Greenbaum-Kasson, E. (2011). "The long way home". The Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Betts, R. (2004). Decolonization. Psychology Press. p. 81.

- ↑ Yanowa, D.; van der Haar, M. (2012). "People out of place: allochthony and autochthony in the Netherlands' identity discourse—metaphors and categories in action". Journal of International Relations and Development. Palgrave Macmillan Journals. 16: 227–261. doi:10.1057/jird.2012.13. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- ↑ Pattynama, P. (2012). "Cultural memory and Indo-Dutch identity formations". The University of Amsterdam: 175–192.

- ↑ Asrianti, Tifa (10 January 2010). "Dutch Indonesians' search for home". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ↑ Laura Jarnagin (2012). Portuguese and Luso-Asian Legacies in Southeast Asia, 1511-2011: Culture and identity in the Luso-Asian world, tenacities & plasticities. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 268.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-02-14. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ↑ L. Hunt, Chester, "Sociology in the Philippine setting: A modular approach", p. 118, Phoenix Pub. House, 1954

- ↑ Frederic H. Sawyer, "The Inhabitants of the Philippines, p. 125, New York, 1900

- ↑ Reid, Anthony (1990). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680: The lands below the winds. Volume 1 of Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680 (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 165. ISBN 0-300-04750-9. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ MacLeod, Murdo J.; Rawski, Evelyn Sakakida, eds. (1998). European Intruders and Changes in Behaviour and Customs in Africa, America, and Asia Before 1800. Volume 30 of An Expanding World, the European Impact on World History, 1450–1800 , Vol 30 (illustrated, reprint ed.). Ashgate. p. 636. ISBN 0-86078-522-X. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Hughes, Sarah S.; Hughes, Brady, eds. (1995). Women in World History: Readings from prehistory to 1500. Volume 1 of Sources and studies in world history (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. p. 219. ISBN 1-56324-311-3. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Tingley, Nancy (2009). Asia Society. Museum, ed. Arts of Ancient Viet Nam: From River Plain to Open Sea. Andreas Reinecke, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (illustrated ed.). Asia Society. p. 249. ISBN 0-300-14696-5. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Hamilton, Alexander (1997). Smithies, Michael, ed. Alexander Hamilton: A Scottish Sea Captain in Southeast Asia, 1689–1723 (illustrated, reprint ed.). Silkworm Books. p. 205. ISBN 9747100452. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- 1 2 Patricia Pok‐kwan Chiu (November 2008). "'A position of usefulness': gendering history of girls' education in colonial Hong Kong (1850s–1890s)". History of Education: Journal of the History of Education Society. Routledge. 37 (6): 799.

- ↑ Meiqi Lee (2004). Being Eurasian: Memories Across Racial Divides (illustrated ed.). Hong Kong University Press. p. 262. ISBN 962-209-671-9. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

EJ Eitel, in the late 1890s, claims that the 'half-caste population in Hong Kong ' were from the earliest days of the settlement almost exclusively the offspring of liaisons between European men and women of outcaste ethnic groups such as Tanka (Europe in , 169). Lethbridge refutes the theory saying it was based on a 'myth' propagated by xenophobic Cantonese to account for the establishment of the Hong Kong Eurasian community. Carl Smith's study in late 1960s on the protected women seems, to some degree, support Eitel's theory. Smith says that the Tankas experienced certain restrictions within the traditional Chinese social structure. Custom precluded their intermarriage with the Cantonese and Hakka-speaking populations. The Tanka women did not have bound feet. Their opportunities for settlement on shore were limited. They were hence not as closely tied to Confucian ethics as other Chinese ethnic groups. Being a group marginal to the traditional Chinese society of the Puntis (Cantonese), they did not have the same social pressure in dealing with Europeans (CT Smith, Chung Chi Bulletin, 27). 'Living under the protection of a foreigner,' says Smith, 'could be a ladder to financial security, if not respectability, for some of the Tanka boat girls' (13 ).

- ↑ Maria Jaschok, Suzanne Miers (1994). Maria Jaschok, Suzanne Miers, ed. Women and Chinese patriarchy: submission, servitude, and escape (illustrated ed.). Zed Books. p. 223. ISBN 1-85649-126-9. Retrieved 2011-11-01.

He states that they had a near- monopoly of the trade in girls and women, and that: The half-caste population in Hong Kong were, from the earliest days of the settlement of the Colony and down to the present day, almost exclusively the offspring of these Tan-ka people. But, like the Tan-ka people themselves, they are happily under the influence of a process of continuous re-absorption in the mass of Chinese residents of the Colony (1895 p. 169)

- ↑ Helen F. Siu (2011). Helen F. Siu, ed. Merchants' Daughters: Women, Commerce, and Regional Culture in South. Hong Kong University Press. p. 305. ISBN 988-8083-48-1. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

"The half-caste population of Hongkong were . . . almost exclusively the offspring of these Tan-ka women." EJ Eitel, Europe in , the History of Hongkong from the Beginning to the Year 1882 (Taipei: Chen-Wen Publishing Co., originally published in Hong Kong by Kelly and Walsh. 1895, 1968), 169.

- ↑ Henry J. Lethbridge (1978). Hong Kong, stability and change: a collection of essays. Oxford University Press. p. 75. Retrieved 2011-11-01.

The half-caste population in Hong Kong were, from the earliest days of the settlement of the Colony and down to the present day [1895], almost exclusively the off-spring of these Tan-ka people

- ↑ Elizabeth Wheeler Andrew, Katharine Caroline Bushnell (1907). Heathen Slaves and Christian Rulers. Echo Library. p. 11. ISBN 1-4068-0431-2.

- ↑ John Mark Carroll (2007). A concise history of Hong Kong. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 36. ISBN 0-7425-3422-7.

Most of the Chinese who came to Hong Kong in the early years were from the lower classes, such as laborers, artisans, Tanka outcasts, prostitutes, wanderers, and smugglers. That these people violated orders from authorities in Canton

- ↑ Henry J. Lethbridge (1978). Hong Kong, stability and change: a collection of essays. Oxford University Press. p. 75.

This exceptional class of Chinese residents here in Hong Kong consists principally of the women known in Hong Kong by the popular nickname " ham-shui- mui " (lit. salt water girls), applied to these members of the so-called Tan-ka or boat

- ↑ Peter Hodge (1980). Peter Hodge, ed. Community problems and social work in Southeast Asia: the Hong Kong and Singapore experience. Hong Kong University Press. p. 33. ISBN 962-209-022-2.

exceptional class of Chinese residents here in Hong Kong consists principally of the women known in Hong Kong by the popular nickname " ham-shui- mui " (lit. salt water girls), applied to these members of the so-called Tan-ka or boat

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-08-22. Retrieved 2016-08-09.

- ↑ "Macau, the imaginary city: culture and society, 1557 to the present". google.co.uk.

- ↑ macau - The Las Vegas of the East >>Inscrutable Chinese>>English>>北京仁和博苑中医药研究院 Archived March 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "9781157453604 - Alibris Marketplace". alibris.com.

- ↑ Between China and Europe: person, culture and emotion in Macao, By João de Pina-Cabral, page 164

- ↑ João de Pina-Cabral (2002). Between China and Europe: person, culture and emotion in Macao. Volume 74 of London School of Economics monographs on social anthropology (illustrated ed.). Berg. p. 165. ISBN 0-8264-5749-5. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

- ↑ Between China and Europe: person, culture and emotion in Macau, By João de Pina-Cabral, page 165 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-05-21. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

- ↑ João de Pina-Cabral (2002). Between China and Europe: person, culture and emotion in Macao. Volume 74 of London School of Economics monographs on social anthropology (illustrated ed.). Berg. p. 39. ISBN 0-8264-5749-5. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

- ↑ "Faculty Profile: Regional Campuses at Ohio University". ohio.edu.

- ↑ Eui-Young Yu and Earl H. Phillips, Korean women in transition: at home and abroad, Center for Korean-American and Korean Studies, California State University, Los Angeles, 1987, p. 185 ISBN 0-942831-00-4.

- ↑ "Japan PM: Moving US base impossible". cntv.cn.

- ↑ Moffett, Samuel H. (1998). A History of Christianity in Asia: 1500–1900. Bishop Henry McNeal Turner Studies in North American Black Religion Series. Volume 2 of A History of Christianity in Asia: 1500–1900. Volume 2 (2, illustrated, reprint ed.). Orbis Books. p. 222. ISBN 1-57075-450-0. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Moffett, Samuel H. (2005). A history of Christianity in Asia, Volume 2 (2 ed.). Orbis Books. p. 222. ISBN 1-57075-450-0. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Free China Review, Volume 11. W.Y. Tsao. 1961. p. 54. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Covell, Ralph R. (1998). Pentecost of the Hills in Taiwan: The Christian Faith Among the Original Inhabitants (illustrated ed.). Hope Publishing House. p. 96. ISBN 0-932727-90-5. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Manthorpe, Jonathan (2008). Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan (illustrated ed.). Macmillan. p. 77. ISBN 0-230-61424-8. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-11-29.

- 1 2 Stark, Herbert Alick. Hostages To India: OR The Life Story of the Anglo Indian Race. Third Edition. London: The Simon Wallenberg Press: Vol 2: Anglo Indian Heritage Books

- 1 2 Fisher, Michael H. (2007), "Excluding and Including "Natives of India": Early-Nineteenth-Century British-Indian Race Relations in Britain", Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 27 (2): 303–314 [304–5], doi:10.1215/1089201x-2007-007

- ↑ Fisher, Michael Herbert (2006), Counterflows to Colonialism: Indian Traveller and Settler in Britain 1600-1857, Orient Blackswan, pp. 111–9, 129–30, 140, 154–6, 160–8, ISBN 81-7824-154-4

- ↑ Fisher, Michael H. (2007), "Excluding and Including "Natives of India": Early-Nineteenth-Century British-Indian Race Relations in Britain", Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 27 (2): 303–314 [305], doi:10.1215/1089201x-2007-007

- ↑ Beckman, Karen Redrobe (2003), Vanishing Women: Magic, Film, and Feminism, Duke University Press, pp. 31–3, ISBN 0-8223-3074-1

- ↑ Kent, Eliza F. (2004), Converting Women, Oxford University Press US, pp. 85–6, ISBN 0-19-516507-1

- ↑ Kaul, Suvir (1996), "Essay: Colonial Figures and Postcolonial Reading", Diacritics, 26 (1): 74–89 [83–9], doi:10.1353/dia.1996.0005

- ↑ Maher, James, Reginald. (2007). These Are The Anglo Indians, London: Simon Wallenberg Press. (An Anglo Indian Heritage Book)

- ↑ Fisher, Michael H. (2007), "Excluding and Including "Natives of India": Early-Nineteenth-Century British-Indian Race Relations in Britain", Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 27 (2): 303–314 [305], doi:10.1215/1089201x-2007-007

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of the Sri Lankan Diaspora Archived September 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Buying and Believing: Sri Lankan Advertising and Consumers in a Transnational World Archived September 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.