Evacuation of civilians from the Channel Islands in 1940

The occupants of the Channel Islands became involved in European events of 1938–39 only as distant and worried listeners to the radio and readers of newspapers. The declaration of War by Britain on 3 September 1939 increased the concern, however life in the islands continued much as normal. By spring 1940 the islands were advertising themselves as holiday destinations.

On 10 May 1940, Belgium and the Netherlands were invaded. Little did the islanders imagine their homes would be under German occupation for five years, before liberation on 9 May 1945.

Time was limited for anyone to evacuate, even so 25,000 people went to England, roughly 17,000 from Guernsey,[1] 6,000 from Jersey and 2,000 from Alderney in the ten days before the German troops landed at the end of June 1940. Most civilians who were evacuated went to England.

Volunteers and early evacuees

The National Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939 passed on 3 September 1939 enforced full conscription on all males between 18 and 41, however it only applied to the United Kingdom and had no effect in the independent Channel Islands. A number of men, especially those who had served in the Royal Guernsey Militia or the Royal Militia of the Island of Jersey as well as men who had been in the Officers' Training Corps at Victoria College, Jersey and Elizabeth College, Guernsey travelled to England, volunteered and were swiftly taken into the armed services. The Jersey militia men leaving as an organised unit.[2]:217

By mid May 1940 the news was not good, Germans were fighting in France and individuals as well as whole families were making plans and taking the ferry to England. Even so, holidaymakers were still coming to the islands. By the beginning of June, the evacuation of Dunkirk was the main topic of conversation, resulting in more people considering leaving the Channel Islands.

Not knowing that on 15 June the British Army commanders had decided the Channel Islands were not defensible, the islanders were surprised to see the resident army units quickly depart on ships, with all of their equipment, the islands were being abandoned.[3]:50 The "Channel Islands had been demilitarised and declared... 'an open town'...",[4] without telling anyone, until after the islands had been bombed on 28 June, as the British government did not want to invite the Germans to take the islands.

June 1940 evacuees

School children

On 19 June the Guernsey local paper published announcements that plans were well in hand to evacuate all the children from the island, telling parents to go to their schools that evening to register and to prepare to send the children away the next day.[5]:1 Some schools asking that the child and their suitcase be brought so it could be checked.[6] Teachers were told they were expected to travel with their children bringing assistants to help, mothers volunteered.

Some schools decided to relocate in total whereas others had their children scattered amongst local schools all over England, Scotland and Wales. 5,000 schoolchildren evacuated and 1,000 stayed with 12 teachers.[7]:193

In Jersey there was no instruction to schools, people could decide themselves if they, or their children, should evacuate. Only 1,000 evacuated with 67 teachers, many travelling with their parents, the remaining 4,500 would remain for the occupation with 140 teachers.[7]:193

Other evacuees

Mothers with children below school age were authorised to go on the first ships, as were men of military age.[5]:41

In Jersey, where the school children were on two weeks holiday to help with the potato harvest, everyone who wished to leave was asked to register, queues quickly appeared, with 23,000 eventually registering.[8]:81 The civil service could not cope and scared of potential riots with desperate people trying to get on ships, announcements that it was best to stay in the island resulted in only about 1,000 Jersey children being evacuated with their parents and 67 teachers.

As soon as the majority of the first wave had departed, ships were made available for anyone else who wished to depart, however with the fear of ships being mobbed, riots amongst travellers and in the empty towns, with looting of empty houses and shops, as had happened in France on the Channel coast, the authorities pushed the message that 'staying was best', with posters saying “Don’t be yellow, stay at home”,[9]:12 (the "patriot" responsible for this poster fled to England).[10]:33 This led to confusion and disorder, especially in Jersey where the authorities did not think it necessary to evacuate children, therefore it was safe for adults to stay.

The reasons why people stayed or evacuated were personal, ranging from fear of the unknown to noble thoughts of continuing the fight with England. Only a few people were put under pressure to either evacuate or stay, often due to their important jobs.

The island authorities assumed that all locals who particularly feared a German occupation would leave the islands, such as people of the Jewish faith. Some certainly did, however it came as a surprise to find out later that others had decided not to leave or who were barred from entering the United Kingdom, because they were "aliens", resulted in around 20 people the Germans would define as "Jewish" becoming trapped in the islands.

Houses, cars and businesses were abandoned by those evacuating. Some locked their front doors, some did not, reasoning that someone would break the door to get in anyway. Some gave away pets, others just released them, many put them down. Some gave away furniture and belongings, some gave it to someone for safe storage,[5]:40 others simply walked away, leaving dirty dishes in the sink and food on the table. The withdrawal of cash from banks was limited to £20 per person. People could take just one suitcase.

The Lieutenant Governor of Jersey and Lieutenant Governor of Guernsey left their islands on board ships on 21 June 1940, the day France surrendered.

Ships

Ships urgently needed to evacuate soldiers from France in Operation Ariel, were diverted to help civilians in the Channel Islands. Marshal Philippe Pétain requested an armistice on 17 June and on 19 June nearby Cherbourg was captured by German forces.

25 ships took people from Guernsey on 21 June alone,[8]:82 ships like the SS Viking, built 1905, served as HMS Vindex until 1918. Requisitioned in 1939 as a troopship, she transported 1,800 schoolchildren from Guernsey to Weymouth.[5]:47 Eighteen ships sailed on 21 June from Jersey including the SS Shepperton Ferry carrying military stores and 400 evacuees. Evacuation ships stopped on 23 June,[8]:82 when ships sailed for England empty.[11]:139 The regular cargo boats and ferries were asked to resume normal service and six evacuation ships were sent to Alderney where previous ships had docked and left almost empty of passengers. 90% of all Channel Island evacuees were taken to Weymouth Harbour, Dorset.[11]:140

Several ships including the Southern Railway SS Isle of Sark, the normal cross channel ferry, were docked in St Peter Port harbour on 28 June when the Luftwaffe arrived and six Heinkel He 111 bombers attacked Guernsey. Lewis machine guns on the ships opened fire, to no visible effect. The bomb damage was mainly to the harbour where lorries loaded with tomatoes for export were lined up, 34 people died.[12] A similar attack occurred in Jersey where nine died. That night the Isle of Sark sailed for England with 647 refugees, she was the last ship to sail, its Captain, Hervy H. Golding being awarded an OBE for his actions that day.[13]

The fact that Guernsey was loading ships with tomatoes rather than people indicates the lack of panic; ships from Guernsey and Jersey designated to carry evacuees were sometimes packed, but others did not sail to their full capacity.[8]:80–81 No hospital ship had arrived to take the elderly and sick away.[8]:84 Several ships, including the Guernsey lifeboat,[14] were machine gunned by German aircraft however with enemy aircraft and submarines operating in the Channel, it was lucky that no evacuation ship was sunk.

Aircraft

R.A.F. units moved from Dinard in France to Jersey on 15 June, No. 17 Squadron RAF and No. 501 Squadron RAF flying sorties until 19 June, in support of the evacuation from Cherbourg, when the aircraft flew to England and the ground support units were evacuated on the SS Train Ferry No. 1.[11]:137 Other military planes were using the Islands, on 17 June 1940, a de Havilland Dragon Rapide DH.89 plane arrived in Jersey from Bordeaux evacuating Général de brigade Charles de Gaulle from France.[15] He stayed for lunch whilst waiting for the plane to be refuelled, before flying on to London.[16]

319 people evacuated the islands on five civilian de Havilland Express DH-86 aircraft, between 16 and 19 June, landing in Exeter.[8]

Evacuees in the UK

Schools

Upon arrival in England, the Guernsey school children were met with mountains of jam sandwiches, bread and butter and tea,[8]:82 before being given a medical and put on crowded blacked out trains, machines most island children had never seen before,[17] to be transported north. 5,000 Guernsey children with their teachers and 500 mothers who became teaching assistants.

- Elizabeth College, Guernsey sent initially to Oldham, moved on to Great Hucklow in Derbyshire

- Intermediate School for Boys merged with Oldham Hulme Grammar School

- Intermediate School for Girls went to Rochdale

- Ladies' College went to Denbigh in Wales

- Forest and St Martin's Schools set up in Cheadle Hulme in Cheshire

- Other primary schools managed to keep pupils together and established themselves in several small communities.[18]

Most Alderney and Jersey school children were scattered, attending different local schools, except Victoria College, Jersey pupils who congregated at Bedford School[18]

In the years to come, children leaving school at the normal age of 14 went into occupations including war industries and would join the Home Guard, 17 year old girls could join the ATS or WLA.[1]

Families

Some reception centres run by The Salvation Army and WVS helpers were surprised to discover that Channel Islanders could speak English, having arranged for translators to be available, islanders answering questions put to them in French with their own local Patois which the translators could not understand.[1] Some ignorant people asked if they had sailed across the Mediterranean and why were they not wearing grass skirts.[19]:143

Stockport had received at least 1,500 refugees and would years later erect a blue plaque to commemorate the event,[1] others went to Bury, Oldham, Wigan, Halifax, Manchester, Glasgow and many other towns.

Some mothers travelling with children whose husbands either stayed in the islands or had joined the armed services initially found attempts were tried to take their children away as it was considered they could not possibly look after them with their husbands away.[19]:143

Women whose husbands were still in the islands were told they were not allowed to rent accommodation, so found they had to match up with a woman whose husband was in the armed services and share a house.[20] Not being able to live on the public assistance monies, one mother would look after the children whilst another mother went out to work, sometimes both worked, one doing a night shift and the other a day shift.[20]

Some houses were not good, previously condemned, damp or bug ridden. Others used empty shops as nothing else was available.[1] If children or families had relatives in the UK, they tended to drift, with their single suitcase of belongings to them, to seek assistance. Some evacuees had brought an elderly relative with them.[21] Islanders were not shy in volunteering for Air Raid Precautions (ARP), Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS), Home Guard or Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) duties in their spare time.

People in the North of England generally rallied to help the evacuees. They were very generous, helping with clothes and shoes, arranging picnics, providing free tickets to cinemas and football matches, lending furniture and donating money for Christmas presents for children.[1]

Safety

Just because thousands had managed to cross the English Channel safely did not mean they would have a safe war. Children from Manchester had recently been evacuated to Canada, as that city was not considered safe, they were replaced by Channel Island children.[1]

Those that joined the armed forces were subject to the usual war risks, those that worked in the UK, whether in war industries or elsewhere were, just like the children, subject to the risk of bombing.[5]:15

Some of the Channel Island children, like some of the 1,500,000 British children[5]:ii that were evacuated from cities in 1939, would suffer mistreatment and abuse, physical, mental and sexual.[22]

There are stories of extorting child labour, stealing the rations of the children, beatings, etc but thankfully they were in the minority and most were rescued by inspectors.[20] For a few, being fostered was a better life than they had had at home.

The psychological damage changed many evacuees, especially children and especially those deprived of their parents, teachers, siblings and friends for five years. Some put up with, even though they hated the experience, most of the children had nobody to talk to about problems and abuse.[23]:275–6 It was not unusual to blame evacuee children if there was vandalism or something went missing. Most were content and more than a few children formed long lasting friendships with loving caring families that looked after them.

Contact and communications

Unlike British refugees, it was not possible to write letters to people at home, or to receive them. Their homes now being occupied by the enemy.

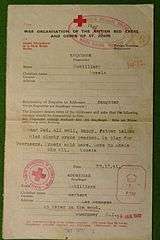

Red Cross messages

Everyone who left the islands left behind friends and relatives. With the islands under German occupation communications were severed. In 1941 the International Red Cross message system, which was designed primarily for use by captured soldiers was, following negotiations, allowed to include civilians in the Channel Islands. In May 1941, the first 7,000 arrived in England.[24]

Limited initially to 10 words per letter, this was later changed to 25, the standard for POWs. The rules changed over the years, at one point islanders were not permitted to write to relatives, but could write to friends. The number of messages one could send were limited. Replies were on the back of the original message. Messages may take months, a few arrived in weeks. All messages routed via the International Red Cross headquarters in Geneva, who dealt with 24 million messages during the war. The islands dealt with around 1 million. Each message sent cost 6d.[25]

To islanders, this tiny link was a saviour, slow and limited, it kept vital contacts and reduced fear of the unknown however not all messages were good; they included notices like "Baby Mary died last December". One family who had two boys in England received a message saying "Your son died in England".[20] Messages ceased shortly after 6 June 1944, when the islands were cut off and isolated.

Societies

The Jersey Society, which had been founded in London in 1896 and acted as a link for Jersey evacuees during the war. The society accumulated over 1,000 books published during the war to restock the libraries in the islands, after the war.[26]

Over 90 local "Channel Island Societies" were established in England, with weekly meetings and arranged social events including card games and dances.[21] Welfare committees were established to help islanders. This allowed the evacuees to maintain contact, talk about their news, gain mutual support and allow children to play together.[1] Islanders serving in the forces would attend meetings when possible.[21]

The Guernsey Society was formed in 1943 to represent the interests of the island to the British Government during the German Occupation, and to establish a network for Guernsey evacuees in the United Kingdom.

Lapel badges were produced to help islanders recognise other evacuees.[21]

20 Upper Grosvenor Street was the contact address for Islanders in London, it provided a legal bureau and held records of where 30,000 Channel Islanders could be found. A room called Le Coin became a home from home for anyone passing through the capital wanting to meet other Islanders.[27]:33

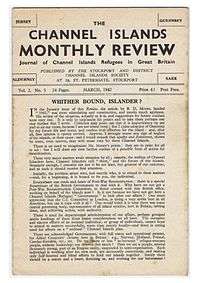

Monthly Review

The Stockport and District Society was founded in January 1941 when 250 prospective members attended the first meeting. They decided to publish the Channel Island Monthly Review, despite a ban on new periodicals since August 1940 due to paper shortages. The first edition, a four page sheet appeared in May 1941, it quickly became popular amongst the thousands of Channel Island people living in the UK. The review was threatened with closure in May 1942 after questions in Parliament.[28]

It did not close and each month the 20-24 page Review was published with up to 5,000 copies a month posted out to subscribers, including service people, all over the world.[1]

The Review included a collection of articles and poetry relevant to Channel Island people and included personal comments received from Red Cross messages that may affect other islanders, such as births marriages and deaths, as well as greeting messages.

Following the Deportations from the German-occupied Channel Islands in September 1942 the December edition of the Review published lists of the deportees and their contact details so Red Cross messages could be sent to them.

Support

The Methodist church tried to keep track of their island members in England, introduce them to English Methodists and to provide them with advice, some money, winter clothing and employment.[29]:172-182

Many Channel Islanders had emigrated to Canada over the years and these got together to help their homeland evacuees, collecting money and sending crates of clothing and shoes.[30]

A "Foster Parent Plan for Children Affected by War" originally created in 1937 to help children in the Spanish Civil War, with Americans adopting a child and providing money for education and clothing. Participants included film stars. Eleanor Roosevelt adopted three children in 1942, one, Paulette, was a Guernsey evacuee, who referred to her as "Auntie Eleanor who lived in the White House".[31]

The BBC recorded island children singing for a Christmas 1942 radio broadcast.[32] The BBC also produced a film of the evacuees showing a rally on 19 June 1943 in the Belle Vue Stadium in Manchester that was attended by 6,000 islanders.[21]

The British Government had opened up an evacuation account for each of the Bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey, to which certain costs could be charged, such as the cost of the evacuation ships, rail travel, the education costs of children. There were concerns over helping Channel Island private schools with their costs as British private schools received no help when evacuated from cities.[18]

Service and death

From the people who had left the Channel Islands in 1939-40 and been evacuated in 1940, over 10,000 islanders served with Allied forces.[33]:294

| Island | Population in 1931 |

Serving in armed forces |

Percentage serving |

Died whilst serving |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50,500 | 5,978 | 11.8% | 516 | |

| 40,600 | 4,011 | 9.8% | 252 | |

| 1,500 | 204 | 13.6% | 25 | |

| 600 | 27 | 4.5% | 1 | |

| Channel Islands | 93,200 | 10,220 | 10.9% | 794 |

| 44,937,000 | 3,500,000 | 7.3% | 383,700 |

A higher percentage of serving people from the islands had died per head of pre-war population than in the UK.

Of those who had stayed in the islands, a higher percentage of civilians died in the islands per head of pre-war population than in the UK.

Return

People began to return in July and August 1945, with some children taking their northern accents with them.[1]

Children, who had not seen their parents for five years often did not recognise them,[1] the adults who had stayed in the islands looked old, tired, thin and wore old clothes. A few children never adjusted to the return, the trauma of separation was too great.[20]

For UK foster parents, the trauma of having the children they had looked after and grown to love taken away could be just as bad.[20] Some children and families kept contact and many hold fond memories and grateful thanks to the people of the north who showed so much kindness.[1] The Mayor of Bolton had threatened the islands with another invasion after liberation, as so many Lancashire holidaymakers would want to see the islands they had heard so much about.[21]

Not all returned, families that had owned no property in the islands had found jobs and houses and some youngsters had found employment and love in their evacuation towns, there was no strong reason to return.[19]:146 Some that did return found the men they had left in the islands had formed a relationship with another woman. No doubt the reverse applied with women finding a new partner. Women, now used to working found no jobs available in the islands apart from scrubbing floors.[19]:147

Many adults returned at the same time as the school children however some who had volunteered for the armed services, were demobbed in 1946. The meetings of families could be equally traumatic, wives and husbands meeting again for the first time in five years, finding they had lived very different lives that were hard to talk about. Those who had been away getting the rejoinder that it was tougher in the islands.[19]:148 Alderney residents were not allowed to return to their island until December 1945.

The UK Government hoping they would be repaid their debt after the war, however the islands ended the war with a debt of £9,000,000,[34]:108 roughly the total value of every house in the Channel Islands, part of this liability being the evacuation accounts. A generous gift from the UK government of £3,300,000 was used to recompense islanders who had suffered losses and in addition, the cost of maintaining the evacuees, estimated at £1,000,000 was written off by the government.[35]:214

See also

- German occupation of the Channel Islands

- Living with the enemy in the German-occupied Channel Islands

- Deportations from the German-occupied Channel Islands

- Resistance in the German-occupied Channel Islands

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "The Experiences of Guernsey Evacuees in Northern England, 1940 – 1945".

- ↑ Lempriére, Raoul. History of the Channel Islands. Robert Hale Ltd. ISBN 978-0709142522.

- ↑ Tabb, Peter. A peculiar occupation. Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7110-3113-5.

- ↑ Falla, Frank (1967). The Silent War. Burbridge. ISBN 0-450-02044-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Laine, Derek. Experiences of a world war II Guernsey evacuee in Cheshire. Betley local history (2009).

- ↑ Strappini, Richard (2004). St Martin, Guernsey, Channel Islands, a parish history from 1204. p. 124.

- 1 2 Lowe, Roy. Education and the Second World War: Studies in Schooling and Social Change. Routledge, 2012. ISBN 978-1-136-59015-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hamon, Simon. Channel Islands Invaded: The German Attack on the British Isles in 1940 Told Through Eye-Witness Accounts, Newspapers Reports, Parliamentary Debates, Memoirs and Diaries. Frontline Books, 2015. ISBN 978-1-4738-5160-3.

- ↑ Le Page, Martin. A Boy Messenger's War: Memories of Guernsey and Herm 1938-45. Arden Publications (1995). ISBN 978-0-9525438-0-0.

- ↑ Chapman, David. Chapel and Swastika: Methodism in the Channel Islands During the German Occupation 1940-1945. ELSP. ISBN 978-1906641085.

- 1 2 3 Channel Islands Occupation Review No 39. Channel Islands Occupation Society. 2011.

- ↑ "The Bombing of Guernsey Harbour 28th June 1940". BBC. 4 August 2014.

- ↑ "The story of an evacuation hero". BBC. 2 December 2009.

- ↑ "Report of Service on the 29th day of June 1940". RNLI.

- ↑ De Gaulle, Charles. The complete war memoirs of Charles de Gaulle. ISBN 0-7867-0546-9.

- ↑ Channel Islands Occupation Review No 39. Channel Islands Occupation Society. p. 55.

- ↑ Strappini, Richard (2004). St Martin, Guernsey, Channel Islands, a parish history from 1204. p. 125.

- 1 2 3 Gosden, Peter. Education in the Second World War: A Study in Policy and Administration. Routledge, 2013. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-1-134-53055-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Andrews, Maggie. The Home Front in Britain: Images, Myths and Forgotten Experiences Since 1914. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. ISBN 978-1-137-34899-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mawson, Gillian. Guernsey Evacuees: The Forgotten Evacuees of the Second World War. The History Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0-7524-9093-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The 'Evacuee Clubs' of Second World War Britain".

- ↑ "'We didn't know where we belonged': Former child evacuees of the Second World War recall their experiences". Daily Mail.

- ↑ Marten, James. Children and War: A Historical Anthology. NYU Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-8147-5667-6.

- ↑ Strappini, Richard (2004). St Martin, Guernsey, Channel Islands, a parish history from 1204. p. 147.

- ↑ "Delivering relief to the Channel Islands in the Second World War". Red Cross UK.

- ↑ "Our History". Guille Allez Public Library.

- ↑ Briggs, Asa. The Channel Islands: Occupation & Liberation, 1940-1945. Trafalgar Square Publishing. ISBN 978-0713478228.

- ↑ "Channel Island Monthly Review". Hansard vol 122 cc991-2. 12 May 1942.

- ↑ Chapman, David. Chapel and Swastika: Methodism in the Channel Islands During the German Occupation 1940-1945. ELSP. ISBN 978-1906641085.

- ↑ "Guernsey evacuees and kind Canadians during the Second World War".

- ↑ "Eleanor Roosevelt: Foster Parent for World War II Refugees". America comes alive.

- ↑ "One small suitcase - Part Five". BBC.

- ↑ Mière, Joe. Never to be forgotten. Channel Island Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9542669-8-1.

- ↑ King, Peter (1991). The Channel Islands War (First ed.). Robert Hale Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7090-4512-0.

- ↑ Ogier, Darryl. The Government and Law of Guernsey. States of Guernsey. ISBN 978-0-9549775-1-1.

Bibliography

- Laine, Derek, (2009), Experiences of a world war II Guernsey evacuee in Cheshire, Betley local history

- Lowe, Roy (2012), Education and the Second World War: Studies in Schooling and Social Change, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-59015-3

- Read, Brian A. (1995), No Cause for Panic – Channel Islands Refugees 1940–45, St Helier: Seaflower Books, ISBN 0-948578-69-6