Fagus sylvatica

| Fagus sylvatica European beech | |

|---|---|

| |

| European beech foliage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Fagaceae |

| Genus: | Fagus |

| Species: | F. sylvatica |

| Binomial name | |

| Fagus sylvatica L. | |

| |

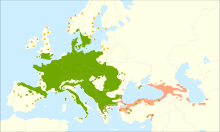

| Distribution map | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Fagus sylvatica, the European beech or common beech, is a deciduous tree belonging to the beech family Fagaceae.

Description

Fagus sylvatica is a large tree, capable of reaching heights of up to 50 m (160 ft) tall[2] and 3 m (9.8 ft) trunk diameter, though more typically 25–35 m (82–115 ft) tall and up to 1.5 m (4.9 ft) trunk diameter. A 10-year-old sapling will stand about 4 m (13 ft) tall. It has a typical lifespan of 150–200 years, though sometimes up to 300 years. In cultivated forest stands trees are normally harvested at 80–120 years of age.[3] 30 years are needed to attain full maturity (as compared to 40 for American beech). Like most trees, its form depends on the location: in forest areas, F. sylvatica grows to over 30 m (100 ft), with branches being high up on the trunk. In open locations, it will become much shorter (typically 15–24 m (50–80 ft)) and more massive.

The leaves are alternate, simple, and entire or with a slightly crenate margin, 5–10 cm long and 3–7 cm broad, with 6–7 veins on each side of the leaf (7–10 veins in Fagus orientalis). When crenate, there is one point at each vein tip, never any points between the veins. The buds are long and slender, 15–30 mm (0.59–1.18 in) long and 2–3 mm (0.079–0.118 in) thick, but thicker (to 4–5 mm (0.16–0.20 in)) where the buds include flower buds.

The leaves of beech are often not abscissed in the autumn and instead remain on the tree until the spring. This process is called marcescence. This particularly occurs when trees are saplings or when plants are clipped as a hedge (making beech hedges attractive screens, even in winter), but it also often continues to occur on the lower branches when the tree is mature.

Small quantities of seeds may be produced around 10 years of age, but not a heavy crop until the tree is at least 30 years old. F. sylvatica male flowers are borne in the small catkins which are a hallmark of the Fagales order (beeches, chestnuts, oaks, walnuts, hickories, birches, and hornbeams). The female flowers produce beechnuts, small triangular nuts 15–20 millimetres (0.59–0.79 in) long and 7–10 mm (0.28–0.39 in) wide at the base; there are two nuts in each cupule, maturing in the autumn 5–6 months after pollination. Flower and seed production is particularly abundant in years following a hot, sunny and dry summer, though rarely for two years in a row.

Distribution and habitat

The natural range extends from southern Sweden to northern Sicily,[4] west to France, southern England, northern Portugal, central Spain, and east to northwest Turkey, where it intergrades with the oriental beech (Fagus orientalis), which replaces it further east. In the Balkans, it shows some hybridisation with oriental beech; these hybrid trees are named Fagus × taurica. In the southern part of its range around the Mediterranean, it grows only in mountain forests, at 600–1,800 m (1,969–5,906 ft) altitude.

Although often regarded as native in southern England, recent evidence suggests that F. sylvatica did not arrive in England until about 4000 BCE, or 2,000 years after the English Channel formed after the ice ages; it could have been an early introduction by Stone age man, who used the nuts for food.[5] The beech is classified as a native in the south of England and as a non-native in the north where it is often removed from 'native' woods.[6] Localised pollen records have been recorded in the North of England from the Iron Age by Sir Harry Godwin. Changing climatic conditions may put beech populations in southern England under increased stress and while it may not be possible to maintain the current levels of beech in some sites it is thought that conditions for beech in north-west England will remain favourable or even improve. It is often planted in Britain. Similarly, the nature of Norwegian beech populations is subject to debate. If native, they would represent the northern range of the species. However, molecular genetic analyses support the hypothesis that these populations represent intentional introduction from Denmark before and during the Viking Age.[7] However, the beech in Vestfold and at Seim north of Bergen in Norway is now spreading naturally and regarded as native.[8]

Though not demanding of its soil type, the European beech has several significant requirements: a humid atmosphere (precipitation well distributed throughout the year and frequent fogs) and well-drained soil (it cannot handle excessive stagnant water). It prefers moderately fertile ground, calcified or lightly acidic, therefore it is found more often on the side of a hill than at the bottom of a clayey basin. It tolerates rigorous winter cold, but is sensitive to spring frost. In Norway's oceanic climate planted trees grow well as far north as Trondheim. In Sweden, beech trees do not grow as far north as in Norway.[9]

A beech forest is very dark and few species of plant are able to survive there, where the sun barely reaches the ground. Young beeches prefer some shade and may grow poorly in full sunlight. In a clear-cut forest a European beech will germinate and then die of excessive dryness. Under oaks with sparse leaf cover it will quickly surpass them in height and, due to the beech's dense foliage, the oaks will die from lack of sunlight.

Ecology

The root system is shallow, even superficial, with large roots spreading out in all directions. European beech forms ectomycorrhizas with a range of fungi including members of the genera Amanita, Boletus, Cantharellus, Hebeloma and Lactarius; these fungi are important in enhancing uptake of water and nutrients from the soil.

In the woodlands of southern Britain, beech is dominant over oak and elm south of a line from about north Suffolk across to Cardigan. Oak are the dominant forest trees north of this line. One of the most beautiful European beech forests called Sonian Forest (Forêt de Soignes/Zoniënwoud) is found in the southeast of Brussels, Belgium. Beech is a dominant tree species in France and constitutes about 10% of French forests. The largest virgin forests made of beech trees are Uholka-Shyrokyi Luh (8,800 ha (22,000 acres)) in Ukraine[10] and Izvoarele Nerei (5,012 ha (12,380 acres) in one forest body) in Semenic-Cheile Carașului National Park, Romania. These habitats are home of Europe's largest predators (the brown bear, the grey wolf and the lynx).[11][12][13] Many trees are older than 350 years in Izvoarele Nerei[14] and even 500 years in Uholka-Shyrokyi Luh.[10]

Spring leaf budding by the European beech is triggered by a combination of day length and temperature. Bud break each year is from the middle of April to the beginning of May, often with remarkable precision (within a few days). It is more precise in the north of its range than the south, and at 600 m (2,000 ft) than at sea level.[15]

The European beech invests significantly in summer and autumn for the following spring. Conditions in summer, particularly good rainfall, determine the number of leaves included in the buds. In autumn, the tree builds the reserves that will sustain it into spring. Given good conditions, a bud can produce a shoot with up to ten or more leaves. The terminal bud emits a hormonal substance in the spring that halts the development of additional buds. This tendency, though very strong at the beginning of their existence, becomes weaker in older trees.

It is only after the budding that root growth of the year begins. The first roots to appear are very thin (with a diameter of less than 0.5 mm). Later, after a wave of above ground growth, thicker roots grow in a steady fashion.

Cultivation

European beech is a very popular ornamental tree in parks and large gardens in temperate regions of the world. In North America, they are preferred for this purpose over the native F. grandifolia, which despite its tolerance of warmer climates, is slower growing, taking an average of 10 years longer to attain maturity. The town of Brookline, Massachusetts has one of the largest, if not the largest, grove of European Beech Trees in the United States. The 2.5 acre public park, called 'The Longwood Mall', was planted sometime before 1850 qualifying it as the oldest stand of European beeches in the United States.[16] It is frequently kept clipped to make attractive hedges. Since the early 19th century there have been numerous cultivars of European beech made by horticultural selection, often repeatedly; they include:

- copper beech or purple beech (Fagus sylvatica Purpurea Group) - leaves purple, in many selections turning deep spinach green by mid-summer. In the United States Charles Sprague Sargent noted the earliest appearance in a nurseryman's catalogue in 1820, but in 1859 "the finest copper beech in America... more than fifty feet high" was noted in the grounds of Thomas Ash, Esq., Throggs Neck, New York;[17] it must have been more than forty years old at the time.

- fern-leaf beech (Fagus sylvatica Heterophylla Group) - leaves deeply serrated to thread-like

- dwarf beech (Fagus sylvatica Tortuosa Group) - distinctive twisted trunk and branches

- weeping beech (Fagus sylvatica Pendula Group) - branches pendulous

- Dawyck beech (Fagus sylvatica 'Dawyck') - fastigiate growth

- golden beech (Fagus sylvatica 'Zlatia') - leaves golden in spring

The following cultivars have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit:-

Image gallery

'Pendula', Harlow Carr.

'Pendula', Harlow Carr. The famous Upside-down Tree, Hyde Park, London, an example of F. sylvatica 'pendula'.

The famous Upside-down Tree, Hyde Park, London, an example of F. sylvatica 'pendula'.- Beech planted on a march dyke (boundary hedge) in Scotland.

- Leaves of var. heterophylla 'Aspleniifolia', Belfast Botanic Garden

Old stand of beech prepared for regenera-tion (note the young undergrowth) in the Sonian Forest.

Old stand of beech prepared for regenera-tion (note the young undergrowth) in the Sonian Forest. Fagus sylvatica wood - MHNT

Fagus sylvatica wood - MHNT Fagus sylvatica - MHNT

Fagus sylvatica - MHNT

Timber

The wood of the European beech is used in the manufacture of numerous objects and implements. Its fine and short grain makes it an easy wood to work with, easy to soak, dye,varnish and glue. Steaming makes the wood even easier to machine. It has an excellent finish and is resistant to compression and splitting. Milling is sometimes difficult due to cracking and it is stiff when flexed. The density of the wood is 720 kg per cubic meter.[25] It is particularly well suited for minor carpentry, particularly furniture. From chairs to parquetry (flooring) and staircases, the European beech can do almost anything other than heavy structural support, so long as it is not left outdoors. Its hardness make it ideal for making wooden mallets and workbench tops. The wood rots easily if it is not protected by a tar based on a distillate of its own bark (as used in railway sleepers).[26][27] It is better for paper pulp than many other broadleaved trees though is only sometimes used for this, the high cellulose content can also be spun into modal, which is used as a textile akin to cotton. The code for its use in Europe is fasy (from FAgus SYlvatica). Common beech is also considered one of the best firewoods for fireplaces.[28]

Other uses

Primary Product AM 01, a smoke flavouring, is produced from Fagus sylvatica L.[29]

The nuts are an important food for birds, rodents and in the past also humans. Slightly toxic to humans if eaten in large quantities due to the tannins and alkaloids they contain, the nuts were nonetheless pressed to obtain an oil in 19th century England that was used for cooking and in lamps. They were also ground to make flour, which could be eaten after the tannins were leached out by soaking.[30][31][32]

Pathogens

Biscogniauxia nummularia (beech tarcrust) is an ascomycete primary pathogen of beech trees, causing strip-canker and wood rot. It can be found at all times of year and is not edible.[33]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "The Plant List".

- ↑ "Tall Trees".

- ↑ Wühlisch, G. (2008). "European beech - Fagus sylvatica" (PDF). EUFORGEN Technical guidelines for genetic conservation and use.

- ↑ Brullo, S.; Guarino, R.; Minissale, P.; Siracusa, G.; Spampinato, G. (1999). "Syntaxonomical analysis of the beech forests from Sicily". Annali di botanica. La Sapienza. 57: 121–132. ISSN 2239-3129. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ↑ Harris, E. (2002). Goodbye to Beech? Farewell to Fagus? Quarterly Journal of Forestry 96 (2): 97.

- ↑ International foresters study Lake District's 'greener, friendlier forests' forestry.gov.uk

- ↑ Myking, T.; Yakovlev, I.; Ersland, G. A. (2011). "Nuclear genetic markers indicate Danish origin of the Norwegian beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) populations established in 500–1,000 AD". Tree Genetics & Genomes. 7 (3): 587–596. doi:10.1007/s11295-010-0358-y.

- ↑ Bøk - en kulturvekst? (Norwegian)

- ↑ Laurie, James; Balbi, Adriano (1842-01-01). System of Universal Geography: Founded on the Works of Malte-Brun and Balbi : Embracing a Historical Sketch of the Progress of Geographical Discovery ... A. and C. Black.

- 1 2 Commarmot, Brigitte; Brändli, Urs-Beat; Hamor, Fedir; Lavnyy, Vasyl (2013). Inventory of the Largest Primeval Beech Forest in Europe (PDF). Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research WSL.

- ↑ Romania & Moldova. Lonely Planet. 1998-01-01. ISBN 9780864423290.

- ↑ Romanescu, Gheorghe; Stoleriu, Cristian Constantin; Enea, Andrei (2013-05-23). Limnology of the Red Lake, Romania: An Interdisciplinary Study. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9789400767577.

- ↑ Apollonio, Marco; Andersen, Reidar; Putman, Rory (2010-02-04). European Ungulates and Their Management in the 21st Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521760614.

- ↑ "Parcul Naţional Semenic - Cheile Caraşului (in Romanian)".

- ↑ Efe, Recep (2014-03-17). Environment and Ecology in the Mediterranean Region II. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 9781443857734.

- ↑ http://www.brooklinema.gov/Facilities/Facility/Details/Longwood-Mall-109

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing and Henry Winthrop Sargent, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America 1859:150.

- ↑ "Fagus sylvatica AGM". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ↑ "Fagus sylvatica 'Dawyck' AGM". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ↑ "Fagus sylvatica 'Dawyck Gold' AGM". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ↑ "Fagus sylvatica 'Dawyck Purple' AGM". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ↑ "Fagus sylvatica 'Pendula' AGM". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ↑ "Fagus sylvatica (Atropurpurea Group) 'Riversii' AGM". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ↑ "Fagus sylvatica var heterophylla 'Aslpeniifolia' AGM". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ↑ Steamed Beech. Niche Timbers. Accessed 20-08-2009.

- ↑ Association, American Wood-Preservers' (1939-01-01). Railroad Tie Decay: Comprising The Decay of Ties in Storage, by C. J. Humphrey ... Defects in Cross Ties, Caused by Fungi, by C. Audrey Richards. American wood-preservers' association.

- ↑ Goltra, William Francis (1912-01-01). Some Facts about Treating Railroad Ties. Press of The J.B. Savage Company.

- ↑ "The burning properties of wood" (PDF). Scoutbase (Scout Information Centre). Scout Association. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ↑ European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Scientific Opinion on Safety of smoke flavour - Primary Product – AM 01 8 January 2010

- ↑ Fergus, Charles; Hansen, Amelia (2005-01-01). Trees of New England: A Natural History. Globe Pequot. ISBN 9780762737956.

- ↑ Fergus, Charles (2002-01-01). Trees of Pennsylvania and the Northeast. Stackpole Books. ISBN 9780811720922.

- ↑ Lyle, Susanna (2006-03-20). Fruit & nuts: a comprehensive guide to the cultivation, uses and health benefits of over 300 food-producing plants. Timber Press.

- ↑ Blanchette, Robert; Biggs, Alan (2013-11-11). Defense Mechanisms of Woody Plants Against Fungi. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783662016428.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to European Beeches. |

- Beech Tree Collection - Photographs By Louis K. Meisel, NY

- Images, location details, and measurements of remarkable beeches

- Den virtuella floran - Distribution

- EUFORGEN species page: Fagus sylvatica Information, distribution and related resources.