Farah Pahlavi

| Farah Pahlavi | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empress of Iran | |||||

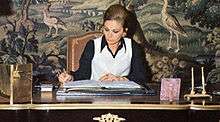

The Empress in 1973 | |||||

| Shahbanu of Iran | |||||

| Tenure | 26 October 1967 – 11 February 1979 | ||||

| Coronation | 26 October 1967 | ||||

| Queen consort of Iran | |||||

| Tenure | 21 December 1959 – 26 October 1967 | ||||

| Born |

14 October 1938 Tehran,[1] Iran | ||||

| Spouse | Mohammad Reza Pahlavi | ||||

| Issue |

Reza, Crown Prince of Iran Princess Farahnaz of Iran Prince Ali-Reza of Iran Princess Leila of Iran | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Pahlavi | ||||

| Father | Sohrab Diba | ||||

| Mother | Farideh Ghotbi | ||||

| Religion | Shia Islam | ||||

| Signature |

| ||||

| Styles of Empress Farah of Iran | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | Her Imperial Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Imperial Majesty |

| Alternative style | Ma'am |

Farah Pahlavi (Persian: فرح پهلوی; born Farah Diba; 14 October 1938) is the widow of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the former Shahbanu (Empress) of Iran.

Childhood

Farah Diba was born on 14 October 1938 in the Iranian capital Tehran, to an upper-class family.[2][3][4] Born as Farah Diba, she was the only child of Captain Sohrab Diba (1899–1948) and his wife, Farideh Ghotbi (1920–2000). Pahlavi's father's family is of Iranian Azerbaijani origin.[3][4] In her memoir, the former Shahbanu writes that her father's family were natives of Iranian Azerbaijan while her mother's family were from Lahijan on the Iranian coast of the Caspian Sea.[5]

Through her father, Farah came from a relatively affluent background. In the late 19th century her grandfather had been an accomplished diplomat, serving as the Iranian Ambassador to the Romanov Court in Moscow, Russia. Her own father was an officer in the Imperial Iranian Armed Forces and a graduate of the prestigious French Military Academy at St. Cyr.

Farah enjoyed an extremely close bond with her father and his unexpected death in 1948 deeply affected her.[5] This situation furthermore left the young family in a difficult financial state. In these reduced circumstances, they were forced to move from their large family villa in northern Tehran into a shared apartment with one of Farideh Ghotbi's brothers.

Education and engagement

The young Farah Diba began her education at Tehran's Italian School, then moved to the French Jeanne d'Arc School until to age of sixteen and later to the Lycée Razi.[6] She was an accomplished athlete in her youth and became captain of her school's basketball team. Upon finishing her studies at the Lycée Razi, she pursued an interest in architecture at the École Spéciale d'Architecture in Paris, where she was a student of Albert Besson.

Many Iranian students who were studying abroad at this time were dependent on State sponsorship. Therefore, when the Shah, as head of state, made official visits to foreign countries, he frequently met with a selection of local Iranian students. It was during such a meeting in 1959 at the Iranian Embassy in Paris that Farah Diba was first presented to Mohammed Reza Pahlavi.

After returning to Tehran in the summer of 1959, the Shah and Farah Diba began a carefully choreographed courtship, orchestrated in part by the Shah's daughter Princess Shahnaz. The couple announced their engagement on 23 November 1959.

Marriage and family

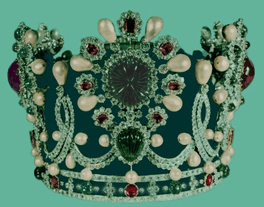

Farah Diba married Shah Mohammed Reza on 20 December 1959, aged 21. The young Queen of Iran (as she was styled at the time) was the object of much curiosity and her wedding received worldwide press attention. Her gown was by Yves Saint Laurent, then a designer at the house of Dior,[7] and she wore the newly commissioned Noor-ol-Ain Diamond tiara.

After the pomp and celebrations associated with the Imperial wedding, the success of this union became contingent upon the Queen’s ability to produce a male heir. Although he had been married twice before, the Shah’s previous marriages had given him only a daughter who, under agnatic primogeniture, could not inherit the throne. The pressure for the young Queen was acute. The Shah himself was deeply anxious to have a male heir as were the members of his government.[8] Furthermore, it was known that the dissolution of the Shah's previous marriage to Queen Soraya had been due to her infertility.[9]

The couple had four children:

- Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi of Iran (born 31 October 1960)

- Princess Farahnaz Pahlavi of Iran (born 12 March 1963)

- Prince Ali Reza Pahlavi of Iran (28 April 1966 – 4 January 2011)

- Princess Leila Pahlavi of Iran (27 March 1970 – 10 June 2001)

As Queen and Empress

_of_Iran_on_the_Steps_Leading_to_the_Truman_Balcony..._-_NARA_-_186813.tif.jpg)

The exact role the new Queen would play, if any, in public or government affairs, was uncertain. Within the Imperial Household, her public function was secondary to the far more pressing matter of assuring the succession. However, after the birth of the Crown Prince, the new Queen was free to devote more of her time to other activities and official pursuits.

Like many other Royal consorts, the young Queen initially limited herself to a ceremonial role. She spent much of her time attending the openings of various education and health-care institutions without venturing too deeply into controversial issues. However, as time progressed, this position changed. The Queen became much more actively involved in government affairs where it concerned issues and causes that interested her. She used her proximity and influence with her husband, the Shah, to secure funding and focus attention on causes, particularly in the areas of women's rights and cultural development.

Eventually, the Queen came to preside over a staff of 40 who handled various requests for assistance on a range of issues. She became one of the most highly visible figures in the Imperial Government and the patron of 24 educational, health and cultural organizations. Her humanitarian role earned her immense popularity for a time, particularly in the early 1970s.[10] During this period, she travelled a great deal within Iran, visiting some of the more remote parts of the country and meeting with the local citizens.

Her significance was exemplified by her part in the 1967 Coronation Ceremonies, where she was crowned as the first shahbanu (empress) of modern Iran. It was again confirmed when the Shah named her as the official regent should he die or be incapacitated before the Crown Prince's 21st birthday. The naming of a woman as regent was highly unusual for a Middle Eastern or Muslim monarchy.[10]

Contributions to art and culture

|

From the beginning of her reign, the Empress took an active interest in promoting culture and the arts in Iran. Through her patronage, numerous organizations were created and fostered to further her ambition of bringing historical and contemporary Iranian Art to prominence both inside Iran and in the Western world.

In addition to her own efforts, the Empress sought to achieve this goal with the assistance of various foundations and advisers. Her ministry encouraged many forms of artistic expression, including traditional Iranian arts (such as weaving, singing, and poetry recital) as well as Western theatre. Her most recognized endeavour supporting the performing arts was her patronage of the Shiraz Arts Festival. This occasionally controversial event was held annually from 1967 until 1977 and featured live performances by both Iranian and Western artists.[11]

The majority of her time, however, went into the creation of museums and the building of their collections.

Ancient art

Historically a culturally rich country, the Iran of the 1960s had little to show for it. Many of the great artistic treasures produced during its 2,500-year history had found their way into the hands of foreign museums and private collections. It became one of the Empress's principal goals to procure for Iran an appropriate collection of its own historic artifacts. To that end, she secured from her husband's government permission and funds to "buy back" a wide selection of Iranian artifacts from foreign and domestic collections. This was achieved with the help of the brothers Houshang and Mehdi Mahboubian, the most prominent Iranian antiquities dealers of the era, who advised the Empress from 1972 to 1978.[12] With these artifacts she founded several national museums (many of which still survive to this day) and began an Iranian version of the National Trust.[13]

Museums and cultural centres created under her guidance include the Negarestan Cultural Center, the Reza Abbasi Museum, the Khorramabad Museum with its valuable collection of Lorestān bronzes, the National Carpet Gallery and the Abgineh Museum for ceramics and glass works.[14]

Contemporary art

Aside from building a collection of historic Iranian artifacts, the Empress also expressed interest in acquiring contemporary Western and Iranian art. To this end, she put her significant patronage behind the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. The fruits of her work in founding and expanding that institution are perhaps the Empress' most enduring cultural legacy to the people of Iran.

Using funds allocated from the Government, the Empress took advantage of a somewhat depressed art market of the 1970s to purchase several important works of Western art. Under her guidance, the Museum acquired nearly 150 works by such artists as Pablo Picasso, Claude Monet, George Grosz, Andy Warhol, Jackson Pollock, and Roy Lichtenstein. Today, the collection of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art is widely considered to be one of the most significant outside Europe and the United States. It is somewhat remarkable then, according to Parviz Tanavoli, a modern Iranian sculptor and a former Cultural Adviser to the Empress, that the impressive collection was amassed for "tens, not hundreds, of millions of dollars".[13] Today, the value of these holdings are conservatively estimated to be near US$2.8 billion.[15]

The collection created a conundrum for the anti-western Islamic Republic which took power after the fall of the Pahlavi Dynasty in 1979. Although politically the fundamentalist government rejected Western influence in Iran, the Western art collection amassed by the Empress was retained, most likely due to its enormous value. It was, nevertheless, not publicly displayed and spent nearly two decades in storage in the vaults of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. This caused much speculation as to the fate of the artwork which was only put to rest after a large portion of the collection was briefly seen again in an exhibition that took place in Tehran during September 2005.[15]

The Iranian Revolution

In Iran by early 1978, a number of factors contributed to the internal dissatisfaction with the Imperial Government becoming more pronounced.

Discontent within the country continued to escalate and later in the year led to demonstrations against the monarchy.[16] The Shahbanu could not help but be aware of the disturbances and records in her memoirs that during this time "there was an increasingly palpable sense of unease". Under these circumstances most of the Shahbanu's official activities were cancelled due to concerns for her safety.[8]

As the year came to a close, the political situation deteriorated further. Riots and unrest grew more frequent, culminating in January 1979. The government enacted martial law in most major Iranian cities and the country was on the verge of an open revolution.

It was at this time, in response to the violent protests, that Mohammad Reza and Farah decided to leave the country. They both departed Iran via aircraft on 16 January 1979.

After leaving Iran

The question of where the Shah and Shahbanu would go after leaving Iran was the subject of some debate, even between the monarch and his advisers.[17] During his reign, Mohammad Reza had maintained close relations with Egyptian President Anwar El Sadat and Farah had developed a close friendship with the President's wife, Jehan Al Sadat. The Egyptian President extended an invitation to the Imperial Couple for asylum in Egypt which they accepted.

Due to the political situation unfolding in Iran, many governments, including those which had been on friendly terms with the Iranian Monarchy prior to the revolution, saw the Shah's presence within their borders as a liability. Although a callous reversal, this was not entirely unfounded as the Revolutionary Government in Iran had ordered the arrest (and later death) of both the Shah and the Shahbanu. The new Iranian Government would go on to vehemently demand their extradition a number of times but the extent to which it would act in pressuring foreign powers for the deposed monarch's return (and presumably that of the Empress) was at that time unknown. Regardless, the predicament was complex.[18]

The Imperial couple were far from unaware of this complexity and cognizant of the potential danger which their presence carried to their host. In response, the Imperial Couple left Egypt, beginning a fourteen-month long search for permanent asylum and a journey which took them through many different countries. After Egypt, they traveled to Morocco, where they were briefly the guests of King Hassan II.

After leaving Morocco, the Shah and Empress were granted temporary refuge in the Bahamas and given use of a small beach property located on Paradise Island. Ironically, Empress Farah recalls the time spent at this pleasantly named location as some of the "darkest days in her life".[8] After their Bahamian visas expired and were not renewed, they made an appeal to Mexico, which was granted, and rented a villa in Cuernavaca near Mexico City.

The Shah's illness

After leaving Egypt the Shah’s health began a rapid decline due to a long-term battle with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The seriousness of that illness brought the now exiled Imperial couple briefly to the United States in search of medical treatment. The couple’s presence in the United States further inflamed the already tense relations between Washington and the revolutionaries in Tehran. The Shah's stay in the US, although for genuine medical purposes, became the tipping point for renewed hostilities between the two nations. These events ultimately led to the attack and takeover of the American Embassy in Tehran in what became known as the Iran hostage crisis.

Under these difficult circumstances, the Shah and Empress were not given permission to remain in the United States. Shortly after receiving basic medical attention, the couple again departed for Latin America, although this time the destination was Contadora Island in Panama.

By now, both the Shah and Empress viewed the Carter Administration with some antipathy in response to a lack of support and were initially pleased to leave. That attitude, however soured as speculation arose that the Panamanian Government was seeking to arrest the Shah in preparation for extradition to Iran.[19] Under these conditions the Shah and Empress again made an appeal to President Anwar El Sadat to return to Egypt (for her part Empress Farah writes that this plea was made through a conversation between herself and Jehan Al Sadat). Their request was granted and they returned to Egypt in March 1980, where they remained until the Shah’s death four months later on 27 July 1980.

Life in exile

After the Shah's death, the exiled Shahbanu remained in Egypt for nearly two years. President Sadat gave her and her family use of Koubbeh Palace in Cairo. A few months after President Sadat’s assassination in October 1981, the Shabanu and her family left Egypt. President Ronald Reagan informed her that she was welcome in the United States.[20]

She first settled in Williamstown, Massachusetts, but later bought a home in Greenwich, Connecticut. After the death of her daughter Princess Leila in 2001, she purchased a smaller home in Potomac, Maryland, near Washington, D.C., to be closer to her son and grandchildren. Farah now divides her time between Washington, D.C, and Paris. She also makes an annual July pilgrimage to the late Shah's mausoleum at Cairo's al-Rifa'i Mosque.

Farah supports charities, including the Annual Alzheimer Gala IFRAD (International Fund Raising for Alzheimer Disease) held in Paris.[21]

Farah Pahlavi continues to appear at certain international royal events, such as the 2004 wedding of Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark, the 2010 wedding of Prince Nikolaos of Greece and Denmark, the 2011 wedding of Albert II, Prince of Monaco and the 2016 wedding of Crown Prince Leka II of Albania.

Grandchildren

Farah Pahlavi currently has three grandchildren (granddaughters) through her son Reza Pahlavi and his wife Yasmine.

- Noor Pahlavi (born 3 April 1992)

- Iman Pahlavi (born 12 September 1993)

- Farah Pahlavi (born 17 January 2004)

Farah Pahlavi also has one granddaughter through her late son Alireza Pahlavi and his companion Raha Didevar.[22]

- Iryana Leila (born 26 July 2011)

Memoir

In 2003, Farah Pahlavi wrote a book about her marriage to Mohammad Reza entitled An Enduring Love: My Life with the Shah. The publication of the former Empress's memoirs attracted international interest. It was a best-seller in Europe, with excerpts appearing in news magazines and the author appearing on talk shows and in other media outlets. However, opinion about the book, which Publishers Weekly called "a candid, straightforward account" and the Washington Post called "engrossing", was mixed.

Elaine Sciolino, the The New York Times's Paris bureau chief, gave the book a less than flattering review, describing it as "well translated" but "full of anger and bitterness".[23] But National Review's Reza Bayegan, an Iranian writer, praised the memoir as "abound[ing] with affection and sympathy for her countrymen."[24]

Documentaries and theater play

In 2009 the Persian-Swedish director Nahid Persson Sarvestani released a feature length documentary about Farah Pahlavi's life, entitled The Queen and I. The film was screened in various International film festivals such as IDFA and Sundance.[25] In 2012 the Dutch director Kees Roorda made a theater play inspired by the life of Farah Pahlavi in exile. In the play Liz Snoijink acted as Farah Diba.[26]

Honours

National dynastic honours

.svg.png) House of Pahlavi:

House of Pahlavi:

- Knight Grand Cordon of the Order of the Light of the Aryans[27][28][29][30]

- Grand Mistress and Dame Grand Cordon of the Order of the Pleiades, 1st Class[27][31][32][33]

- Recipient of the Persepolis Medal[27]

- Recipient of the Commemorative Medal of the 2,500 year Celebration of the Persian Empire[27]

- Recipient of the Emperor Reza Shah I Centennial Medal

Foreign honours

-

Argentina: Grand Cross of the Order of the Liberator General San Martin[27]

Argentina: Grand Cross of the Order of the Liberator General San Martin[27] -

Austria: Grand Cross of the Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria, Grand Star[34][35]

Austria: Grand Cross of the Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria, Grand Star[34][35] -

.svg.png) Belgium: Dame Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold[36][37]

Belgium: Dame Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold[36][37] -

Brazil: Grand Cross of the Order of the Southern Cross[27]

Brazil: Grand Cross of the Order of the Southern Cross[27] -

Brunei: Dame Grand Cross of the Royal Family Order of the Crown of Brunei[38]

Brunei: Dame Grand Cross of the Royal Family Order of the Crown of Brunei[38] -

Czech Republic: Grand Cross of the Order of the White Lion[39]

Czech Republic: Grand Cross of the Order of the White Lion[39] -

Denmark: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Elephant[27]

Denmark: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Elephant[27] -

.svg.png) Ethiopian Imperial Family: Dame Grand Cordon with Collar of the Order of the Queen of Sheba[40][41]

Ethiopian Imperial Family: Dame Grand Cordon with Collar of the Order of the Queen of Sheba[40][41] -

France: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour[42][43]

France: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour[42][43] -

Germany: Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, Special Class[44]

Germany: Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, Special Class[44] -

Italy: Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic[45]

Italy: Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic[45] -

Japan: Paulownia Dame Grand Cordon of the Order of the Precious Crown[27]

Japan: Paulownia Dame Grand Cordon of the Order of the Precious Crown[27] -

Jordan: Dame Grand Cordon of the Supreme Order of the Renaissance[46][47]

Jordan: Dame Grand Cordon of the Supreme Order of the Renaissance[46][47] -

Malaysia: Honorary Recipient of the Order of the Crown of the Realm[48][49]

Malaysia: Honorary Recipient of the Order of the Crown of the Realm[48][49] -

Mexico: Grand Cross of the Order of the Aztec Eagle, Special Class[50]

Mexico: Grand Cross of the Order of the Aztec Eagle, Special Class[50] -

Morocco: Dame of the Order of Muhammad, 1st Class[51]

Morocco: Dame of the Order of Muhammad, 1st Class[51] -

Netherlands: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion[52][53]

Netherlands: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion[52][53] -

Netherlands: Recipient of the Silver Wedding Anniversary Medal of Queen Juliana and Prince Bernhard[54]

Netherlands: Recipient of the Silver Wedding Anniversary Medal of Queen Juliana and Prince Bernhard[54] -

Norway: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of St. Olav[27][55]

Norway: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of St. Olav[27][55] -

Poland: Knight of the Order of the Smile[56]

Poland: Knight of the Order of the Smile[56] -

Spain: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic[57][58]

Spain: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic[57][58] -

Sweden: Member Grand Cross of the Order of the Seraphim[27]

Sweden: Member Grand Cross of the Order of the Seraphim[27] -

Thailand: Dame Grand Cordon with Chain of the Order of the Royal House of Chakri[59][60][61][62]

Thailand: Dame Grand Cordon with Chain of the Order of the Royal House of Chakri[59][60][61][62] -

Tunisia: Grand Cross of the Order of Independence[63]

Tunisia: Grand Cross of the Order of Independence[63] -

Yugoslavia: Grand Cross of the Order of the Yugoslav Star, Great Star[27]

Yugoslavia: Grand Cross of the Order of the Yugoslav Star, Great Star[27]

Awards

National

Foreign

-

Austria:[65]

Austria:[65] -

France: Honorary Citizen of Bruges-Capbis-Mifaget[66]

France: Honorary Citizen of Bruges-Capbis-Mifaget[66] -

France: Foreign Associate Academician of the Académie des Beaux-Arts[67]

France: Foreign Associate Academician of the Académie des Beaux-Arts[67] -

Germany: Steiger Award[68]

Germany: Steiger Award[68] -

Germany: Südwestfalen Charlie Award[69]

Germany: Südwestfalen Charlie Award[69] -

Israel: Tel Aviv University Peace Prize[70]

Israel: Tel Aviv University Peace Prize[70] -

United States: Honorary Degree of the American University[71]

United States: Honorary Degree of the American University[71] -

United States: National Museum of Women in the Arts Award for International Patronage[72]

United States: National Museum of Women in the Arts Award for International Patronage[72]

See also

References

- ↑ The life and times of the Shah. Books.google. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ↑ Afkhami, Gholam Reza. The life and times of the Shah (1 ed.). University of California Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-520-25328-5.

- 1 2 Shakibi, Zhand (2007). Revolutions and the Collapse of Monarchy: Human Agency and the Making of Revolution in France, Russia, and Iran. I.B. Tauris. p. 90. ISBN 1-84511-292-X.

- 1 2 Taheri, Amir. The Unknown Life of the Shah. Hutchinson, 1991. ISBN 0-09-174860-7; p. 160

- 1 2 Pahlavi, Farah. ‘An Enduring Love: My life with The Shah. A Memoir’ 2004

- ↑ "Empress Farah Pahlavi Official Site - سایت رسمی شهبانو فرح پهلوی". farahpahlavi.org.

- ↑ "The Royal Order of Sartorial Splendor: Wedding Wednesday: Empress Farah's Gown". orderofsplendor.blogspot.com.

- 1 2 3 Pahlavi, Farah. ‘An Enduring Love: My Life with The Shah. A Memoir’ 2004

- ↑ Queen of Iran Accepts Divorce As Sacrifice, The New York Times, 15 March 1958, p. 4.

- 1 2 "The World: Farah: The Working Empress". Time. 4 November 1974. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ Robert Gluck. "The Shiraz Arts Festival: Western Avant-Garde Arts in 1970s Iran". Mitpressjournals.org. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ Norman, Geraldine (13 December 1992). "Mysterious gifts from the East". The Independent. London. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- 1 2 de Bellaigue, Christopher (7 October 2005). "Lifting the veil". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ Pahlavi, Farah. "An Enduring Love: My Life with The Shah. A Memoir" 2004

- 1 2 "Iran: We Will Put American Art Treasures on Display". ABC News. 7 March 2008. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ↑ "1978: Iran's PM steps down amid riots". BBC News. 5 November 1978. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Answer to History, Stein & Day Pub, 1980

- ↑ "Shah's Dilemma". Time Magazine.

- ↑ "The Shah's Flight". Time Magazine.

- ↑ Pahlavi, Farah. "An Enduring Love: My life with Shah. A Memoir" 2004

- ↑ "Enduring Friendship: Alain Delon and Shahbanou Farah Pahlavi at annual Alzheimer Gala in Paris". Payvand. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ↑ "Announcement of Birth". Reza Pahlavi. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ Sciolino, Elaine (2 May 2004). "The Last Empress". The New York Times.

- ↑ Bayegan, Reza (13 May 2004). "The Shah & She". National Review.

- ↑ "The Queen and I". sundance.org.

- ↑ "Farah Diba, World's Prettiest Woman: Premiere in Haarlem". iranian.com. 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "pahlavi3". Royalark.net. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Photographic image". Geourdu.co. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- ↑ "Photographic image" (JPG). 41.media.tumblr.com. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Photographic image" (JPG). Alexandrakinias.files.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- ↑ "Empress Farah Pahlavi of Iran". Getty Images. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑

- ↑ "Royal and Historic Jewelry - Page 4 - the Fashion Spot". Forums.thefashionspot.com. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Reply to a parliamentary question" (PDF) (in German). p. 193. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ↑ "Photographic image" (JPG). Farm2.staticflickr.com. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- ↑ "Photographic image" (JPG). Images.thetrumpet.com. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- ↑ "Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi of Iran". Getty Images. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑

- ↑ "Kolana Řádu Bílého lva aneb hlavy států v řetězech". Vyznamenani.net. 2010-06-25. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ Ismael. "Royal State Visits: Visita de Estado de Irán a Etiopía - 1968". Royalstatevisits.blogspot.com.es. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Photographic image" (JPG). 2.bp.blogpsot.com. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- ↑ "Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi of Iran". Getty Images. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "The Royal Watcher : Photo". Royalwatcher.tumblr.com. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Photographic image" (JPG). 41.media.tumblr.com. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "FARAH PAHLAVI S.M.I. decorato di Gran Cordone" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ↑ "Empress Farah Pahlavi of Iran". Getty Images. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Photographic image" (JPG). 40.media.tumblr.com. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Photographic image" (JPG). 36.media.tmblr.com. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- ↑ "Photographic image" (JPG). 40.media.tumblr.com. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ http://revistas.bancomext.gob.mx/rce/magazines/713/14/SEPTIEMBRE_1975_SUPLEMENTO.pdf

- ↑ "Casa Imperial de Irán: Visita de Estado a Marruecos - 1968". Casaimperialdeiran.blogspot.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Het geheugen van Nederland". Geheugenvannederland.nl. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Het geheugen van Nederland". Geheugenvannederland.nl. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Photographic image" (JPG). S-media.cache.oinimg.com. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- ↑ "Photographic image" (JPG). 40.media.tumblr.com. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ Beata (2008-09-12). "Where are our smiles from?: The Order of the Smile". Oursmiles-etwinning.blogspot.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "1lI. Otras disposicionel" (PDF). Boletín Oficial del Estado (in Spanish). 13 November 1969. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ↑ "Juan Carlos I". Getty Images. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Photographic image" (JPG). Pricescope.com. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- ↑ "Photographic image" (JPG). Theroyalforums.com. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Photographic image" (JPG). Theroyalforums.com. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Photographic image" (JPG). 40.media.tumblr.com. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Casa Imperial de Irán: Visita de Estado a Túnez - 1969". Casaimperialdeiran.blogspot.co.uk. 2012-08-31. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑

- ↑ Archived 26 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Farah Pahlavi Official Site". Farahpahlavi.org. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Farah Pahlavi Official Site". Farahpahlavi.org. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Farah Pahlavi Official Site". Farahpahlavi.org. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Farah Pahlavi Official Site" (PDF). Farahpahlavi.org. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Farah Pahlavi Official Site". Farahpahlavi.org. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Diaries of an Exiled Persian: American University's Honorary Doctorate for Queen Farah of Persia". Exiledpersian.blogspot.co.uk. 2015-01-03. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "Farah Pahlavi Official Site" (PDF). Farahpahlavi.org. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Farah Pahlavi. |

- Official website

- Biography Portal Shahbanu Farah Pahlavi (Persian)

- Farah Pahlavi, Iran's Ex-Empress, Receives the Anne Morrow Lindbergh Grace and Distinction Award 2005

- Shahram Razavi's online photo album "Imperial Iran of the Pahlavi Dynasty"

- A web site dedicated to Reza Shah Kabir (the great) including video clip and photos

| Iranian royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vacant Title last held by Sorayâ Esfandiyâri |

Queen consort of Iran 1959–1967 |

Became Empress |

| Preceded by Herself as Queen |

Empress consort of Iran 1967–1979 |

Monarchy abolished |