Fiber laser

A fiber laser or fibre laser is a laser in which the active gain medium is an optical fiber doped with rare-earth elements such as erbium, ytterbium, neodymium, dysprosium, praseodymium, thulium and holmium. They are related to doped fiber amplifiers, which provide light amplification without lasing. Fiber nonlinearities, such as stimulated Raman scattering or four-wave mixing can also provide gain and thus serve as gain media for a fiber laser.

Advantages and applications

The advantages of fiber lasers over other types include:

- Light is already coupled into a flexible fiber: The fact that the light is already in a fiber allows it to be easily delivered to a movable focusing element. This is important for laser cutting, welding, and folding of metals and polymers.

- High output power: Fiber lasers can have active regions several kilometers long, and so can provide very high optical gain. They can support kilowatt levels of continuous output power because of the fiber's high surface area to volume ratio, which allows efficient cooling.

- High optical quality: The fiber's waveguiding properties reduce or eliminate thermal distortion of the optical path, typically producing a diffraction-limited, high-quality optical beam.

- Compact size: Fiber lasers are compact compared to rod or gas lasers of comparable power, because the fiber can be bent and coiled to save space.

- Reliability: Fiber lasers exhibit high temperature and vibrational stability, extended lifetime, and maintenance-free turnkey operation.

- High peak power and nanosecond pulses enable effective marking and engraving.

- The additional power and better beam quality provide cleaner cut edges and faster cutting speeds.

- Lower cost of ownership.

- Fiber lasers are now being used to make high-performance surface-acoustic wave (SAW) devices. These lasers raise throughput and lower cost of ownership in comparison to older solid-state laser technology.[1]

Fiber laser can also refer to the machine tool that includes the fiber resonator.

Applications of fiber lasers include material processing (marking, engraving, cutting), telecommunications, spectroscopy, medicine, and directed energy weapons.[2]

Design and manufacture

Unlike most other types of lasers, the laser cavity in fiber lasers is constructed monolithically by fusion splicing different types of fiber; fiber Bragg gratings replace conventional dielectric mirrors to provide optical feedback. Another type is the single longitudinal mode operation of ultra narrow distributed feedback lasers (DFB) where a phase-shifted Bragg grating overlaps the gain medium. Fiber lasers are pumped by semiconductor laser diodes or by other fiber lasers. Q-switched pulsed fiber lasers offer a compact, electrically efficient alternative to Nd:YAG technology.[1]

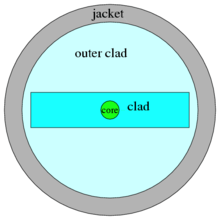

Double-clad fibers

Many high-power fiber lasers are based on double-clad fiber. The gain medium forms the core of the fiber, which is surrounded by two layers of cladding. The lasing mode propagates in the core, while a multimode pump beam propagates in the inner cladding layer. The outer cladding keeps this pump light confined. This arrangement allows the core to be pumped with a much higher-power beam than could otherwise be made to propagate in it, and allows the conversion of pump light with relatively low brightness into a much higher-brightness signal. As a result, fiber lasers and amplifiers are occasionally referred to as "brightness converters." There is an important question about the shape of the double-clad fiber; a fiber with circular symmetry seems to be the worst possible design.[3][4][5][6][7][8] The design should allow the core to be small enough to support only a few (or even one) modes. It should provide sufficient cladding to confine the core and optical pump section over a relatively short piece of the fiber.

Power scaling

Recent developments in fiber laser technology have led to a rapid and large rise in achieved diffraction-limited beam powers from diode-pumped solid-state lasers. Due to the introduction of large mode area (LMA) fibers as well as continuing advances in high power and high brightness diodes, continuous-wave single-transverse-mode powers from Yb-doped fiber lasers have increased from 100 W in 2001 to >20 kW. Commercial single-mode lasers have reached 10 kW in CW power.[9] In 2014 a combined beam fiber laser demonstrated power of 30 kW.[10]

Mode locking

Passive mode locking

Nonlinear polarization rotation

When linearly polarized light is incident to a piece of weakly birefringent fiber, the polarization of the light will generally become elliptically polarized in the fiber. The orientation and ellipticity of the final light polarization is fully determined by the fiber length and its birefringence. However, if the intensity of the light is strong, the non-linear optical Kerr effect in the fiber must be considered, which introduces extra changes to the light polarization. As the polarization change introduced by the optical Kerr effect depends on the light intensity, if a polarizer is put behind the fiber, the light intensity transmission through the polarizer will become light intensity dependent. Through appropriately selecting the orientation of the polarizer or the length of the fiber, an artificial saturable absorber effect with ultra-fast response could then be achieved in such a system, where light of higher intensity experiences less absorption loss on the polarizer. The NPR technique makes use of this artificial saturable absorption to achieve the passive mode locking in a fiber laser. Once a mode-locked pulse is formed, the non-linearity of the fiber further shapes the pulse into an optical soliton and consequently the ultrashort soliton operation is obtained in the laser. Soliton operation is almost a generic feature of the fiber lasers mode-locked by this technique and has been intensively investigated.

Semiconductor saturable absorber mirrors (SESAMs)

Semiconductor saturable absorbers were used for laser mode-locking as early as 1974 when p-type germanium is used to mode lock a CO2 laser which generated pulses ~500 ps . Modern SESAMs are III-V semiconductor single quantum well (SQW) or multiple quantum wells grown on semiconductor distributed Bragg reflectors (DBRs). They were initially used in a Resonant Pulse Modelocking (RPM) scheme as starting mechanisms for Ti:Sapphire lasers which employed KLM as a fast saturable absorber . RPM is another coupled-cavity mode-locking technique. Different from APM lasers which employ non-resonant Kerr-type phase nonlinearity for pulse shortening, RPM employs the amplitude nonlinearity provided by the resonant band filling effects of semiconductors. SESAMs were soon developed into intracavity saturable absorber devices because of more inherent simplicity with this structure. Since then, the use of SESAMs has enabled the pulse durations, average powers, pulse energies and repetition rates of ultrafast solid-state lasers to be improved by several orders of magnitude. Average power of 60 W and repetition rate up to 160 GHz were obtained. By using SESAM-assisted KLM, sub-6 fs pulses directly from a Ti: Sapphire oscillator was achieved. A major advantage SESAMs have over other saturable absorber techniques is that absorber parameters can be easily controlled over a wide range of values. For example, saturation fluence can be controlled by varying the reflectivity of the top reflector while modulation depth and recovery time can be tailored by changing the low temperature growing conditions for the absorber layers . This freedom of design has further extended the application of SESAMs into modelocking of fiber lasers where a relatively high modulation depth is needed to ensure self-starting and operation stability. Fiber lasers working at ~ 1 µm and 1.5 µm were successfully demonstrated.[11][12][13][14][15][16]

Graphene saturable absorbers

Graphene is a one-atom-thick planar sheet of sp2-bonded carbon atoms that are densely packed in a honeycomb crystal lattice. Optical absorption from graphene can become saturated when the input optical intensity is above a threshold value. This nonlinear optical behavior is termed saturable absorption and the threshold value is called the saturation fluency. Graphene can be saturated readily under strong excitation over the visible to near-infrared region, due to the universal optical absorption and zero band gap.[17] This has relevance for the mode locking of fiber lasers, where wideband tunability may be obtained using graphene as the saturable absorber.[18] Due to this special property, graphene has wide application in ultrafast photonics.[19][20][21] Furthermore, comparing with the SWCNTs, as graphene has a 2D structure it should have much smaller non-saturable loss and much higher damage threshold. Self-started mode locking and stable soliton pulse emission with high energy have been achieved with a graphene saturable absorber in an erbium-doped fiber laser.[22][23][24] Atomic layer graphene possesses wavelength-insensitive ultrafast saturable absorption, which can be exploited as a “full-band” mode locker. With an erbium-doped dissipative soliton fiber laser mode locked with few layer graphene, it has been experimentally shown that dissipative solitons with continuous wavelength tuning as large as 30 nm (1570–1600 nm) can be obtained.[25]

Active mode locking

Active mode-locking is normally achieved by modulating the loss (or gain) of the laser cavity at a repetition rate equivalent to the cavity frequency, or a harmonic thereof. In practice, the modulator can be acousto-optic or electro-optic modulator, Mach-Zehnder integrated-optic modulators, or a semiconductor electro-absorption modulator (EAM). The principle of active mode-locking with a sinusoidal modulation. In this situation, optical pulses will form in such a way as to minimize the loss from the modulator. The peak of the pulse would automatically adjust in phase to be at the point of minimum loss from the modulator. Because of the slow variation of sinusoidal modulation, it is not very straightforward for generating ultrashort optical pulses (< 1ps) using this method.

For stable operation, the cavity length must precisely match the period of the modulation signal or some integer multiple of it. The most powerful technique to solve this is regenerative mode locking i.e. a part of the output signal of the mode-locked laser is detected; the beatnote at the round-trip frequency is filtered out from the detector, and sent to an amplifier, which drives the loss modulator in the laser cavity. This procedure enforces synchronism if the cavity length undergoes fluctuations due to acoustic vibrations or thermal expansion. By using this method, highly stable mode-locked lasers have been achieved. The major advantage of active mode-locking is that it allows synchronized operation of the mode-locked laser to an external radio frequency (RF) source. This is very useful for optical fiber communication where synchronization is normally required between optical signal and electronic control signal. Also active mode-locked fiber can provide much higher repetition rate than passive mode-locking. Currently, fiber lasers and semiconductor diode lasers are the two most important types of lasers where active mode-locking are applied.

Dark soliton fiber lasers

In the non-mode locking regime,the first dark soliton fiber laser has been successfully achieved in an all-normal dispersion erbium-doped fiber laser with a polarizer in cavity. Experimentally finding that apart from the bright pulse emission, under appropriate conditions the fiber laser could also emit single or multiple dark pulses. Based on numerical simulations we interpret the dark pulse formation in the laser as a result of dark soliton shaping.[26]

Multiwavelength fiber lasers

Recently,multiwavelength dissipative soliton in an all normal dispersion fiber laser passively mode-locked with a SESAM has been generated. It is found that depending on the cavity birefringence, stable single-, dual- and triple-wavelength dissipative soliton can be formed in the laser. Its generation mechanism can be traced back to the nature of dissipative soliton.[15]

Fiber disk lasers

Another type of fiber laser is the fiber disk laser. In such lasers, the pump is not confined within the cladding of the fiber, but instead pump light is delivered across the core multiple times because the core is coiled on itself like a rope. This configuration is suitable for power scaling in which many pump sources are used around the periphery of the coil.[27][28][29][30] Fiber disk lasers have exceptional protection against back reflection compared to traditional fiber lasers. Fiber disk lasers can be used for welding and cutting applications requiring more than 1000 watts of power.

See also

References

- 1 2 Patel, A.; Lincoln, B.; Stone, D. (April 1, 2013). "Specialty Fiber: Fiber lasers lower cost of making SAW's". Laser Focus World. 49 (4): 59. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ↑ Popov, S. (2009). "7: Fiber laser overview and medical applications". In Duarte, F. J. Tunable Laser Applications (2nd ed.). New York: CRC.

- ↑ S. Bedo; W. Luthy; H. P. Weber (1993). "The effective absorption coefficient in double-clad fibers". Optics Communications. 99 (5–6): 331–335. Bibcode:1993OptCo..99..331B. doi:10.1016/0030-4018(93)90338-6.

- ↑ A. Liu; K. Ueda (1996). "The absorption characteristics of circular, offset, and rectangular double-clad fibers". Optics Communications. 132 (5–6): 511–518. Bibcode:1996OptCo.132..511A. doi:10.1016/0030-4018(96)00368-9.

- ↑ Kouznetsov, D.; Moloney, J.V. (2003). "Efficiency of pump absorption in double-clad fiber amplifiers. 2: Broken circular symmetry". JOSAB. 39 (6): 1259–1263. Bibcode:2002JOSAB..19.1259K. doi:10.1364/JOSAB.19.001259.

- ↑ Kouznetsov, D.; Moloney, J.V. (2003). "Efficiency of pump absorption in double-clad fiber amplifiers.3:Calculation of modes". JOSAB. 19 (6): 1304–1309. Bibcode:2002JOSAB..19.1304K. doi:10.1364/JOSAB.19.001304.

- ↑ Leproux, P.; S. Fevrier; V. Doya; P. Roy; D. Pagnoux (2003). "Modeling and optimization of double-clad fiber amplifiers using chaotic propagation of pump". Optical Fiber Technology. 7 (4): 324–339. Bibcode:2001OptFT...7..324L. doi:10.1006/ofte.2001.0361.

- ↑ D.Kouznetsov; J.Moloney (2004). "Boundary behaviour of modes of a Dirichlet Laplacian". Journal of Modern Optics. 51 (13): 1362–3044. Bibcode:2004JMOp...51.1955K. doi:10.1080/09500340408232504.

- ↑ "IPG Photonics offers world's first 10 kW single-mode production laser". June 17, 2009. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ↑ "Many lasers become one in Lockheed Martin's 30 kW fiber laser". Gizmag.com. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ↑ H. Zhang et al, “Induced solitons formed by cross polarization coupling in a birefringent cavity fiber laser”, Opt. Lett., 33, 2317–2319.(2008).

- ↑ D.Y. Tang et al, “Observation of high-order polarization-locked vector solitons in a fiber laser”, Physical Review Letters, 101, 153904 (2008).

- ↑ "BATOP GmbH - Welcome". Batop.com. 2013-05-25. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ↑ H. Zhang et al, “Coherent energy exchange between components of a vector soliton in fiber lasers”, Optics Express, 16,12618–12623 (2008).

- 1 2 H. Zhang et al, “Multi-wavelength dissipative soliton operation of an erbium-doped fiber laser”, Optics Express, Vol. 17, Issue 2, pp.12692-12697

- ↑ L.M. Zhao et al, “Polarization rotation locking of vector solitons in a fiber ring laser”, Optics Express, 16,10053–10058 (2008).

- ↑ Z. Sun, T. Hasan, F. Torrisi, D. Popa, G. Privitera, F. Wang, F. Bonaccorso, D. M. Basko and A. C. Ferrari, ACS Nano,"Graphene Mode-Locked Ultrafast Laser" doi:10.1021/nn901703e

- ↑ Z. Sun, D. Popa, T. Hasan, F. Torrisi, F. Wang, E. Kelleher, J. Travers, V. Nicolosi and A. Ferrari, Nano Research,"A stable, wideband tunable, near transform-limited, graphene-mode-locked, ultrafast laser" doi:10.1007/s12274-010-0026-4

- ↑ Qiaoliang Bao, Han Zhang, Yu Wang, Zhenhua Ni, Yongli Yan, Ze Xiang Shen, Kian Ping Loh,and Ding Yuan Tang, Advanced Functional Materials,"Atomic layer graphene as saturable absorber for ultrafast pulsed lasers"

- ↑ H. Zhang; D. Y. Tang; L. M. Zhao; Q. L. Bao; K. P. Loh. "Large energy mode locking of an erbium-doped fiber laser with atomic layer graphene" (PDF). Optics Express. 17: P17630. arXiv:0909.5536

. Bibcode:2009OExpr..1717630Z. doi:10.1364/OE.17.017630.

. Bibcode:2009OExpr..1717630Z. doi:10.1364/OE.17.017630. - ↑ F. Bonaccorso, Z. Sun, T. Hasan and A. C. Ferrari, Nature Photonics,"Graphene photonics and optoelectronics" doi:10.1038/nphoton.2010.186

- ↑ Han Zhang; Qiaoliang Bao; Dingyuan Tang; Luming Zhao; Kianping Loh. "Large energy soliton erbium-doped fiber laser with a graphene-polymer composite mode locker" (PDF). Applied Physics Letters. 95: P141103. arXiv:0909.5540

. Bibcode:2009ApPhL..95n1103Z. doi:10.1063/1.3244206.

. Bibcode:2009ApPhL..95n1103Z. doi:10.1063/1.3244206. - ↑ Archived February 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Nanotechnology Spotlight Articles – Category , page 1". Nanowerk. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ↑ Zhang, H. et al., (2010). "Graphene mode locked, wavelength-tunable, dissipative soliton fiber laser" (PDF). Applied Physics Letters. 96 (11): 111112. arXiv:1003.0154

. Bibcode:2010ApPhL..96k1112Z. doi:10.1063/1.3367743.

. Bibcode:2010ApPhL..96k1112Z. doi:10.1063/1.3367743. - ↑ Han Zhang, Dingyuan Tang, Luming Zhao and Wu Xuan,“Dark pulse emission of a fiber laser" PHYSICAL REVIEW A 80, 045803 2009

- ↑ K. Ueda; A. Liu (1998). "Future of High-Power Fiber Lasers". Laser Physics. 8: 774–781.

- ↑ K. Ueda (1999). "Scaling physics of disk-type fiber lasers for kW output" (PDF). Lasers and Electro-Optics Society. 2: 788–789. doi:10.1109/leos.1999.811970.

- ↑ Ueda; Sekiguchi H.; Matsuoka Y.; Miyajima H.; H.Kan (1999). "Conceptual design of kW-class fiber-embedded disk and tube lasers". Lasers and Electro-Optics Society 1999 12th Annual Meeting. LEOS '99. IEEE. 2: 217–218. doi:10.1109/CLEOPR.1999.811381. ISBN 0-7803-5661-6.

- ↑ Hamamatsu Photonics K.K. Laser group (2006). "The Fiber Disk Laser explained". Nature Photonics. sample: 14–15. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2006.6.