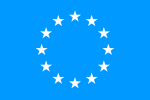

Flag of Europe

| |

| Proportion | 2:3 |

|---|---|

| Adopted |

8 December 1955[1] (CoE) 29 June 1985[2] (EEC) |

| Design | A circle of 12 5-pointed gold (yellow) stars on an azure (blue) field. |

| Designed by | Arsène Heitz, Paul M. G. Lévy |

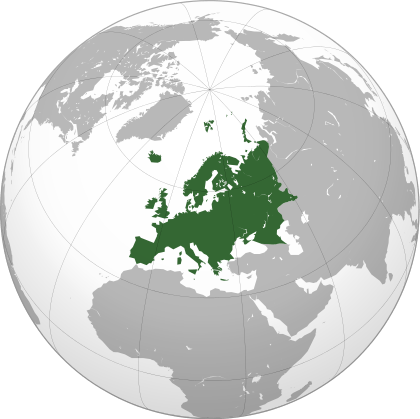

The Flag of Europe, or European Flag is the flag of Europe. It consists of a circle of 12 golden (yellow) stars on an azure background. It is an official symbol of two separate organizations — the Council of Europe (CoE) and the European Union (EU) — both of which term it the "Flag of Europe" or the "European Flag". It was first adopted in 1955 by the Council of Europe to represent the European continent as a whole. Due to the subsequent emergence of the EU, the flag is sometimes colloquially known as the "flag of the European Union", but this term is not official.[3]

The flag was designed in 1955, and officially launched later that year by the Council of Europe as a symbol for the whole of Europe.[4] The Council of Europe urged it to be adopted by other European organisations, and in 1985 the European Economic Community (EEC) adopted it as its own flag (having had no flag of its own before) at the initiative of the European Parliament.

The flag is not mentioned in the EU's treaties, its incorporation being dropped along with the European Constitution, but it is formally adopted in law. The Council of Europe has a distinctive "Council of Europe Logo" to uniquely identify the organisation, which employs a lower-case "e" in the centre. The logo is not meant to be a substitute for the flag, which the Council flies in front of and in its headquarters, annexes and field office premises.

Since its adoption by the European Union, it has become broadly associated with the supranational organisation due to its high profile and heavy usage of the emblem. However, the flag is sometimes use in its wider denotation, for example representing Europe in sporting events and as a pro-democracy banner.[5][6] It has partly inspired other flags, such as those of other European organisations and those of sovereign states where the EU has been heavily involved (such as Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina).

History

Creation

The search for a symbol began in 1950 when a committee was set up in order to look into the question of a European flag. There were numerous proposals but a clear theme for stars and circles emerged.[7] Count Richard Nikolaus von Coudenhove-Kalergi proposed that they adopt the flag of his International Paneuropean Union, which was a blue field, with a red cross inside an orange circle at the centre, which he had himself recently adopted for the European Parliamentary Union.[8] Due to the cross symbolism, this was rejected by Turkey (a member of the Council of Europe since 1949).[9] Kalergi then suggested adding a crescent to the cross design, to overcome the Muslim objections.[10] Another organisation's flag was the European Movement, which had a large green E on a white background.[11][12] A further design was one based on the Olympic rings: eight silver rings on a blue background. It was rejected due to the rings' similarity with "dial", "chain" and "zeros". One proposal had a large yellow star on a blue background, but it was rejected due to its similarity with the so-called Burnet flag and the flag of the Belgian Congo.[9]

The Consultative Assembly narrowed their choice to two designs. One was by Salvador de Madariaga, the founder of the College of Europe, who suggested a constellation of stars on a blue background[13] (positioned according to capital cities, with a large star for Strasbourg, the seat of the Council). He had circulated his flag round many European capitals and the concept had found favour.[14] The second was a variant by Arsène Heitz,[13] who worked for the Council's postal service and had submitted dozens of designs;[15] the design of his that was accepted by the Assembly was similar to Salvador de Madariaga's, but rather than a constellation, the stars were arranged in a circle.[13] In 1987, Heitz claimed that his inspiration had been the crown of twelve stars of the Woman of the Apocalypse, often found in Marian iconography (see below).[16]

The Consultative Assembly favoured Heitz's design. However, the flag the Assembly chose had fifteen stars, reflecting the number of states of the Council of Europe. The Consultative Assembly chose this flag and recommended the Council of Europe to adopt it.[17] The Committee of Ministers (the Council's main decision making body) agreed with the Assembly that the flag should be a circle of stars, but the number was a source of contention.[7] The number twelve was chosen, and Paul M. G. Lévy drew up the exact design of the new flag as it is today.[7] The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe approved it on 25 October 1955. Adopted on 8 December 1955, the flag was unveiled at the Château de la Muette in Paris on 13 December 1955.[2][13]

- Unsuccessful entries

The original flag of the Paneuropean Union

The original flag of the Paneuropean Union

The original flag of the European Movement

The original flag of the European Movement

European Communities

Following Expo 58 in Brussels, the flag caught on and the Council of Europe lobbied for other European organisations to adopt the flag as a sign of European unity.[13] The European Parliament took the initiative in seeking a flag to be adopted by the European Communities. Shortly after the first direct elections in 1979 a draft resolution was put forward on the issue. The resolution proposed that the Communities' flag should be that of the Council of Europe[2] and it was adopted by the Parliament on 11 April 1983.[13]

The June 1984 European Council (the Communities' leaders) summit in Fontainebleau stressed the importance of promoting a European image and identity to citizens and the world. The following year, meeting in Milan, the 28–29 June European Council approved a proposal from the Committee on a People’s Europe (Adonnino Committee) in favour of the flag and adopted it. Following the permission of the Council of Europe,[2] the Communities began to use it from 1986, with it being raised outside the Berlaymont building (the seat of the European Commission) for the first time on 29 May 1986.[18] The European Union, which was established by the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 to replace the EC and encompass its functions, also adopted the flag. Since then the use of the flag has been controlled jointly by the Council of Europe and the European Union.[2]

Previous flags

Prior to development of political institutions, flags representing Europe were limited to unification movements. The most popular were the European Movement's large green 'E' on a white background, and the "Pan European flag" (see "Creation" below).[13] With the development of institutions, aside from the Council of Europe, came other emblems and flags. None were intended to represent wider Europe and have since been replaced by the current flag of Europe.

The first major organisation to adopt one was the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), which merged into the European Communities. The ECSC was created in 1952 and the flag of the ECSC was unveiled in 1958 Expo in Brussels.[19]

The flag had two stripes, blue at the top, black at the bottom with six gold (silver after 1973) stars, three on each stripe. Blue was for steel, black for coal and the stars were the six member-states. The stars increased with the members until 1986 when they were fixed at twelve. When the ECSC treaty expired in 2002, the flag was lowered outside the European Commission in Brussels and replaced with the European flag.[19][20][21]

The European Parliament also used its own flag from 1973, but never formally adopted it. It fell out of use with the adoption of the twelve star flag by the Parliament in 1983. The flag followed the yellow and blue colour scheme however instead of twelve stars there were the letters EP and PE (initials of the European Parliament in the six community languages at the time) surrounded by a wreath.[22]

Barcode flag

In 2002, Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas and his architecture firm Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) designed a new flag in response to Commission President Romano Prodi's request to find ways of rebranding the Union in a way that represents Europe's "diversity and unity". The proposed new design was dubbed the "barcode", as it displays the colours of every European flag (of the then 15 members) as vertical stripes. As well as the barcode comparison, it had been compared unfavourably to wallpaper, a TV test card, and deckchair fabric. Unlike the current flag, it would change to reflect the member states.[23]

It was never officially adopted by the EU or any organisation; however, it was used as the logo of the Austrian EU Presidency in 2006. It had been updated with the colours of the 10 members who had joined since the proposal, and was designed by Koolhaas's firm. Its described aim is "to portray Europe as the common effort of different nations, with each retaining its own unique cultural identity".[24] There were initially some complaints, as the stripes of the flag of Estonia were displayed incorrectly.

Recent events

In April 2004, the flag was flown in space for the first time by European Space Agency astronaut André Kuipers while on board the International Space Station.[25]

Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, Lithuania, Luxemburg, Hungary, Malta, Austria, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia and the Slovak Republic declare that the flag with a circle of twelve golden stars on a blue background, the anthem based on the ‘Ode to Joy’ from the Ninth Symphony by Ludwig van Beethoven, the motto ‘United in diversity’, the euro as the currency of the European Union and Europe Day on 9 May will for them continue as symbols to express the sense of community of the people in the European Union and their allegiance to it.

Final Act, Official Journal of the European Union, 2007 C 306–2[26]

The flag was to have been given a formal status in the proposed European Constitution. However, since the ratification of that failed, the leaders removed the state-like elements such as the flag from the replacement Treaty of Lisbon. The European Parliament however had supported the inclusion of symbols, and in response backed a proposal to use the symbols, such as the flag more often in the Parliament. Jo Leinen MEP suggesting that the Parliament should again take the avant-garde in their use.[27] Later, in September 2008, Parliament's Committee on Constitutional Affairs proposed a formal change in the institution's rules of procedure to make better use of the symbols. Specifically, the flag would be present in all meeting rooms (not just the hemicycle) and at all official events.[28] The proposal was passed on 8 October 2008 by 503 votes to 96 (15 abstentions).[29]

Additionally, a declaration by sixteen Member States on the symbols, including the flag, was included in the final act of the Treaty of Lisbon stating that the flag, the anthem, the motto and the currency and Europe Day "will for them continue as symbols to express the sense of community of the people in the European Union and their allegiance to it."[26]

Usage

Council of Europe

.jpg)

The flag was originally designed by the Council of Europe,[2] and as such the CoE holds the copyright for the flag. However, the Council of Europe agreed that the European Communities could use the flag and it had promoted its use by other regional organisations since it was created. The Council of Europe now shares responsibility with the European Commission for ensuring that use of the symbol respects the dignity of the flag—taking measures to prevent misuse of it.[2]

Besides using the flag, the Council also uses a defaced version of the flag as its emblem: it is the existing design with a stylised, green "e" over the stars.[2]

European Union

The flag symbolises the EU as a whole.[30] All EU institutions, bodies and agencies have their own logo or emblem, albeit often inspired by the flag's design and colours.[31] As part of the EU's usage, the flag appears on the euro banknotes.[32] Euro coins also display the twelve stars of the flag on both the national and common sides[33] and the flag is sometimes used as an indication of the currency or the eurozone (a collective name for those countries that use the Euro). The flag appears also on many driving licences and vehicle registration plates issued in the Union.[34]

Protocol

It is mandatory for the flag to be used in every official speech made by the President of the European Council and it is often used at official meetings between the leaders of an EU state and a non-EU state (the national flag and European flag appearing together).[34] While normally the national flag takes precedence over the European flag in the national context, meetings between EU leaders sometimes differ. For example, the Italian flag code expressly replaces the Italian flag for the European flag in precedence when dignitaries from other EU countries visit – for example the EU flag would be in the middle of a group of three flags rather than the Italian flag.[35]

The flag is usually flown by the government of the country holding the rotating presidency Council of Ministers, though in 2009 the Czech President Václav Klaus, a eurosceptic, refused to fly the flag from his castle. In response, Greenpeace projected an image of the flag onto the castle and attempted to fly the flag from the building themselves.[36]

Some members also have their own rules regarding the use of the flag alongside their national flag on domestic occasions, for example the obligatory use alongside national flags outside police stations or local government buildings. As an example according to the Italian laws it is mandatory for most public offices and buildings to hoist the European Flag alongside the Italian national Flag (Law 22/2000 and Presidential Decree 121/2000). Outside official use, the flag may not be used for aims incompatible with European values.[34]

In national usage, national protocol usually demands the national flag takes precedence over the European flag (which is usually displayed to the right of the national flag from the observer's perspective). On occasions where the European flag is flown alongside all national flags (for example, at a European Council meeting), the national flags are placed in alphabetical order (according to their name in the main language of that state) with the European flag either at the head, or the far right, of the order of flags.[37][38]

Extraordinary flying of the flag is common on the EU's flag day, known as Europe Day, which is celebrated annually on 9 May.[39][40][41] On Europe Day 2008, the flag was flown for the first time above the German Reichstag.[42]

Military and naval use

In addition to the flags use by the government and people, the flag is also used in EU military operations;[43] however, it is not used as a civil ensign. In 2003, a member of the European Parliament tabled a proposal in a temporary committee of the European Parliament that national civil ensigns be defaced with the European flag. This proposal was rejected by Parliament in 2004, and hence the European flag is not used as a European civil ensign.[44]

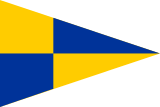

Despite not having a civil ensign, the EU's Fishery Inspection teams display a blue and yellow pennant. The pennant is flown by inspection vessels in EU waters. The flag is triangular and quartered blue and yellow and was adopted according to EEC Regulation #1382/87 on 20 May 1978.[45] There are no other variants or alternative flags used by the EU (in contrast to countries which have presidential, naval and military variants).

Ukraine

The flag became a symbol of European integration of Ukraine in the 2010s, particularly after Euromaidan. Ukraine is not a part of the EU but is a member of the Council of Europe. The flag is used by the Cabinet of Ukraine, Prime Minister of Ukraine, and MFA UA during official meetings.[46]

Wider use

The flag has been used to represent Europe in its wider sense. The Council of Europe covers all but three European countries, thereby representing much of Europe.[2]

In particular, the flag has become a banner for pro-Europeanism outside the Union, for example in Georgia, where the flag is on most government buildings since the coming to power of Mikhail Saakashvili,[47] who used it during his inauguration,[48] stating: "[the European] flag is Georgia’s flag as well, as far as it embodies our civilisation, our culture, the essence of our history and perspective, and our vision for the future of Georgia."[49] It was later used in 2008 by pro-western Serbian voters ahead of an election.[50]

It is also used as a pro-democracy emblem in countries such as Belarus, where it has been used on protest marches alongside the banned former national flag and flags of opposition movements.[5][51] The flag was used widely in a 2007 European March in Minsk as protesters rallied in support of democracy and accession to the EU.[52] Similarly, the flag was flown during the 2013 Euromaidan pro-democracy and pro-EU protests in Ukraine.

The flag, or features of it, are often used in the logos of organisations of companies which stress a pan-European element, for example European lobbyist groups or transnational shipping companies.

The flag is also used in certain sports arrangements where a unified Team Europe is represented as in the Ryder Cup and the Mosconi Cup.

Following the 2004 Summer Olympics, President Romano Prodi pointed out that the combined medal total of the European Union was far greater than that of any other country and called for EU athletes to fly the European flag at the following games alongside their own as a sign of solidarity (which did not happen).[53]

The design of the European flag was displayed on the Eiffel Tower in Paris to celebrate the French presidency of the EU Council in the second half of 2008.

Design

.svg.png)

The flag is rectangular with 2:3 proportions: its fly (width) is one and a half times the length of its hoist (height). Twelve gold (or yellow) stars are centred in a circle (the radius of which is a third of the length of the hoist) upon a blue background. All the stars are upright (one point straight up), have five points and are spaced equally according to the hour positions on the face of a clock. The diameter of each star is equal to one-ninth of the height of the hoist.[54][55]

The heraldic description given by the EU is: "On an azure field a circle of twelve golden mullets, their points not touching."[56] The Council of Europe gives the flag a symbolic description in the following terms;

Against the blue sky of the Western world, the stars represent the peoples of Europe in a circle, a symbol of unity. Their number shall be invariably set at twelve, the symbol of completeness and perfection.— Council of Europe. Paris, 7–9 December 1955[57]

Colours

| PMS | RGB approx. | Hexadecimal | CMYK [%] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| red | green | blue | process cyan | process magenta | process yellow | process black | |||

| Blue | Navy | 0 | 51 | 153 | 003399 | 100 | 67 | 0 | 40 |

| Gold | Gold | 255 | 204 | 0 | FFCC00 | 0 | 20 | 100 | 0 |

The base colour of the flag is a dark blue (reflex blue, a mix of cyan and magenta), while the golden stars are portrayed in Yellow. The colours are regulated according to the Pantone colouring system (see table for specifications).

A large number of designs[13] were proposed for the flag before the current flag was agreed. The rejected proposals are preserved in the Council of Europe Archives. One of these consists of a design of white stars on a light blue field, as a gesture to the peace and internationalism of the United Nations.[9] An official website makes a reference to blue and gold being the original colours of Count Richard Nikolaus von Coudenhove-Kalergi, who proposed a Pan European Union in 1923, and was an active proponent of the early Community.[19][58]

Number of stars

The number of stars on the flag is fixed at 12, and is not related to the number of member states of the EU (although the EU did have 12 member states from 1986 to 1994). This is because it originally was the flag of the Council of Europe.[30] In 1953, the Council of Europe had 15 members; it was proposed that the future flag should have one star for each member, and would not change based on future members. West Germany objected to this as one of the members was the disputed area of Saarland, and to have its own star would imply sovereignty for the region.[14] Twelve was eventually adopted as a number with no political connotations and as a symbol of unity.[30] In his 2006 book Boris Johnson drew attention to the Emperor Necklace which depicts twelve Caesars, and looks 'uncannily like the euro flag'.[59] While 12 is the correct number of stars, sometimes flags or emblems can be found that incorrectly show 15 (as of the rejected proposal) or 25 (as suggested by some after the expansion of the EU to 25 member states in 2004).[60][61] However, the flag also remains that of the Council of Europe, which now has 47 member states.

Derivative designs

The design of the European flag has been used in a variation, such as that of the Council of Europe mentioned above, and also to a greater extent such as the flag of the Western European Union (WEU; now defunct), which uses the same colours and the stars but has a number of stars based on membership and in a semicircle rather than a circle. It is also defaced with the initials of the former Western European Union in two languages.[62]

The flag of Bosnia and Herzegovina does not have such a strong connection as the WEU flag, but was partly inspired by the European involvement in, and aspirations of, Bosnia and Herzegovina. It uses the same blue and yellow colours and the stars, although of a different number and colour, are a direct reference to those of the European flag.[63]

Likewise, the Republic of Kosovo uses blue, yellow and stars in its flag in reference to the European flag, symbolising its European ambitions (membership of the European Union). Kosovo has, like Bosnia and Herzegovina, seen heavy European involvement in its affairs, with the European Union assuming a supervisory role after its declared independence in 2008.[64][65]

The flag of the Brussels-Capital Region consists of a yellow iris with a white outline upon a blue background. Its colours are based on the colours of the Flag of Europe, because Brussels is considered the unofficial capital of the EU.

The national flag of Cape Verde also shows similarity to the flag of the European Union. The flag is made of a circular formation of ten yellow stars on a dark blue background and a band of white and red. The stars represent the main islands of the nation (a chain of islands off the coast of West Africa). The blue represents the ocean and the sky. The band of white and red represents the road toward the construction of the nation, and the colours stand for peace (white) and effort (red). The flag was adopted on 22 September 1992.

Other labels take reference to the European flag such as the EU organic food label that uses the twelve stars but reorders them into the shape of a leaf on a green background. The original logo of the European Broadcasting Union used the twelve stars on a blue background adding ray beams to connect the countries.

Marian interpretation

In 1987, following the adoption of the flag by the EEC, Arsène Heitz (1908–89), one of the designers who had submitted proposals for the flag's design, suggested a religious inspiration for it. He claimed that the circle of stars was based on the iconographic tradition of showing the Blessed Virgin Mary as the Woman of the Apocalypse, wearing a "crown of twelve stars".[66][68] The French satirical magazine Le Canard enchaîné reacted to Heitz's statement with an article entitled L’Europe violée par la Sainte Vierge ("Europe Raped by the Blessed Virgin") in the 20 December 1989 edition. Heitz also made a connection to the date of the flag's adoption, 8 December 1955, coinciding with the Catholic Feast of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Paul M. G. Lévy, then Director of Information at the Council of Europe responsible for designing the flag, in a 1989 statement maintained that he had not been aware of any religious connotations.[69]

In an interview given 26 February 1998, Lévy denied not only awareness of the "Marian" connection, but also denied that the final design of a circle of twelve stars was Heitz's. To the question "Who really designed the flag?" Lévy replied:

- "I did, and I calculated the proportions to be used for the geometric design. Arsène Heitz, who was an employee in the mail service, put in all sorts of proposals, including the 15-star design. But he submitted too many designs. He wanted to do the European currencies with 15 stars in the corner. He wanted to do national flags incorporating the Council of Europe flag."[68]

Carlo Curti Gialdino (2005) has reconstructed the design process to the effect that Heitz's proposal contained varying numbers of stars, from which the version with twelve stars was chosen by the Committee of Ministers meeting at Deputy level in January 1955 as one out of two remaining candidate designs.[68]

Lévy's 1998 interview apparently gave rise to a new variant of the "Marian" anecdote. An article published in Die Welt in August 1998 alleged that it was Lévy himself who was inspired to introduce a "Marian" element as he walked past a statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary.[70]

An article posted in La Raison in February 2000 further connected the donation of a stained glass window for Strasbourg Cathedral by the Council of Europe on 21 October 1956. This window, a work by Parisian master Max Ingrand, shows a blessing Madonna underneath a circle of 12 stars on dark blue ground.[71] The overall design of the Madonna is inspired by the banner of the cathedral's Congrégation Mariale des Hommes, and the twelve stars are found on the statue venerated by this congregation inside the cathedral (twelve is also the number of members of the congregation's council).[72]

Similar flags

See also

- Circle of stars

- Federalist flag

- Flag of the European Coal and Steel Community

- Flag of the Western European Union

- Symbols of Europe

- Flag of the African Union

References

- ↑ Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe (8 December 1955), Resolution (55) 32 of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, CVCE, retrieved 25 June 2014

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Council of Europe's Emblems, Council of Europe, archived from the original on 7 August 2007, retrieved 16 August 2007

- ↑ European Union, The European flag, Retrieved: 25 May 2016

- ↑ The European flag, Council of Europe. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- 1 2 Mite (20 October 2004), Belarus: Scores Arrested, Opposition Leader Hospitalized After Minsk Protests, rferl.org, retrieved 5 August 2007

- ↑ Romania slams Moldova's sanctions

- 1 2 3 Account by Paul M. G. Lévy, a Belgian Holocaust survivor on the creation of the European flag, CVCE, retrieved 25 June 2014

- ↑ Letter to the secretary general of the Council of Europe from Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi, Council of Europe (French)

- 1 2 3 Council of Europe fahnenversand.de

- ↑ Letter from Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi regarding a Muslim modification to the Pan-Europa flag design, Council of Europe (French)

- ↑ European Movement crwflags.com

- ↑ Proposals for the European flag Archived 15 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine. crwflags.com

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 CVCE (ed.), The European flag: questions and answers, retrieved 25 June 2014

- 1 2 Murphy, Sean (25 January 2006), Memorandum on the Role of Irish Chief Herald Slevin in the Design of the European Flag, Centre for Irish Genealogical and Historical Studies, archived from the original on 5 December 2008, retrieved 2 February 2009

- ↑ Lettre d’Arsène Heitz à Filippo Caracciolo (Strasbourg, 5 janvier 1952), CVCE, retrieved 25 June 2014

- ↑ "Real politics, at last". The Economist. 2004-10-28. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ↑ Recommendation 56(1) of the Consultative Assembly on the choice of an emblem for the Council of Europe (25 September 1953), CVCE, retrieved 25 June 2014

- ↑ Raising of the European flag in front of the Berlaymont (Brussels, 29 May 1986), CVCE, retrieved 25 June 2014

- 1 2 3 The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), Flags of the World, 28 October 2004, retrieved 4 August 2007

- ↑ The ECSC flag 1986–2002, CVCE

- ↑ The ECSC flag 1978, CVCE

- ↑ European Parliament, Flags of the World, 28 October 2004, retrieved 4 August 2007

- ↑ Down with EU stars, run up stripes, BBC News, 8 May 2002

- ↑ Austrian EU Presidency Logo, Dexigner

- ↑ Further steps towards a European space policy, European Space Agency, retrieved 11 February 2009

- 1 2 Official Journal of the European Union, 2007 C 306–2 , p. 267

- ↑ Beunderman, Mark (11 July 2007), MEPs defy member states on EU symbols, EU Observer, retrieved 12 July 2007

- ↑ EU Parliament set to use European flag, anthem, EU Business, 11 September 2008, archived from the original on 12 September 2008, retrieved 12 September 2008

- ↑ Kubosova, Lucia (9 October 2008), No prolonged mandate for Barroso, MEPs warn, EU Observer, retrieved 9 October 2008

- 1 2 3 The European Flag, Europa (web portal), retrieved 4 August 2007

- ↑ Emblems, Europa (web portal), retrieved 28 December 2007

- ↑ The euro, European Central Bank, archived from the original on 6 August 2007, retrieved 4 August 2007

- ↑ Euro coins, European Central Bank, archived from the original on 24 December 2007, retrieved 28 December 2007

- 1 2 3 European Union: Legal use of the flag, Flags of the World, 10 September 2005, archived from the original on 18 November 2009, retrieved 29 November 2009

- ↑ The Rules of Protocol regarding national holidays and the use of the Italian flag Archived 19 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Presidency of the Council of Ministers, Department of Protocol (Retrieved 5 October 2008)

- ↑ Greenpeace projects EU flag image on Prague Castle, Ceske Noviny, 7 January 2009, retrieved 21 January 2009

- ↑ An Bhratach Náisiúnta / The National Flag (RTF), Department of the Taoiseach, retrieved 28 December 2007

- ↑ A Guide to Flag Protocol in the United Kingdom (PDF), Flag Institute, retrieved 28 December 2007

- ↑ Rasmussen, Rina Valeur, Celebration of Europe Day 9 May 2007 in Denmark, Politeia, retrieved 4 August 2007

- ↑ Photo from Reuters Pictures, Reuters Images, on Daylife, 9 May 2008, retrieved 9 May 2008

- ↑ Rasmussen, Rina Valeur (9 May 2007), London Eye lights up in colours of the European flag, Europa (web portal), archived from the original on 19 August 2007, retrieved 4 August 2007

- ↑ Photo from Reuters Pictures, Reuters Images, on Daylife, 9 May 2008, retrieved 9 May 2008

- ↑ EUFOR Welcome Ceremony/Unfolding EU flag, NATO, archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2008, retrieved 14 April 2008

- ↑ Rejected proposal of a European civil ensign, Flags of the World, retrieved 14 April 2008

- ↑ European Union Fishery Inspection, Flags of the World, 3 February 2008, retrieved 15 July 2008

- ↑ http://www.kmu.gov.ua/control/en/photogallery/gallery?galleryId=247776574&

- ↑ Petersen, Alex (1 May 2007), Comment – Georgia: Brussels on its mind, EU Observer, retrieved 1 May 2007

- ↑ Saakashvili Sworn In as New President, Templeton Thorp, retrieved 4 August 2007

- ↑ Petersen, Alexandros (2 May 2007), Georgia: Brussels on its mind, Global Power Europe, retrieved 25 August 2007

- ↑ Photo from Reuters Pictures, Reuters Images, on Daylife, 9 May 2008, archived from the original on 25 June 2008, retrieved 9 May 2008

- ↑ Myers, Steven Lee; Chivers, C.J. (20 March 2006), "Election is landslide for leader of Belarus", International Herald Tribune, archived from the original on 15 May 2008, retrieved 9 July 2016

- ↑ Belarusians had European March in Mins, charter97.org, 14 October 2007, retrieved 25 November 2007

- ↑ Rachman, Gideon (22 September 2006), "The Ryder Cup and Euro-nationalism", Financial Times, retrieved 17 August 2008

- ↑ Graphical specifications for the European flag, Council of Europe, archived from the original on 16 June 2008, retrieved 26 July 2008

- ↑ Graphical specifications for the European Emblem, Communication department of the European Commission, retrieved 16 June 2011

- ↑ Graphical specifications for the European Emblem, European Commission, retrieved 4 August 2004

- ↑ Thirty-sixth meeting of the ministers' deputies: resolution (55) 32 (PDF), Council of Europe, 9 December 1955, retrieved 2 February 2008

- ↑ Do the Number of Stars on the European Flag Represent the Member States?, European Commission's delegation to Ukraine, retrieved 11 July 2008

- ↑ Johnson, Boris (2006). "2". The Dream of Rome. London: HarperPress. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-00-722441-8.

- ↑ Sache, Ivan (17 July 2004). "Number of stars on the flag of the European Union". Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ↑ "European Economic Community Flag 2". Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ↑ Western European Union, Flags of the World, retrieved 11 February 2009

- ↑ Bosnia and Herzegovina – The 1998 Flag Change – Westendorp Commission – The Choice), Flags of the World, retrieved 11 February 2009

- ↑ "Kosovo's fiddly new flag", The Economist, 18 February 2008, retrieved 11 February 2009

- ↑ Kosovo's Flag Revealed, Balkan Insight, 17 February 2008, archived from the original on 18 June 2008, retrieved 11 February 2009

- 1 2 "The European Commission and religious values". The Economist. 28 October 2004. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- ↑ Large full version of the window, venez-chez-domi.fr, archived from the original on 27 February 2009, retrieved 28 January 2009

- 1 2 3 Carlo Curti Gialdino, I Simboli dell'Unione europea, Bandiera - Inno - Motto - Moneta - Giornata. Roma: Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato S.p.A., 2005. ISBN 88-240-2503-X, pp. 80–85. Gialdino is here cited after a translation of the Italian text published by the Centre Virtuel de la Connaissance sur l'Europe (cvce.eu): "Irrespective of the statements by Paul M. G. Levy and the recent reconstruction by Susan Hood, crediting Arsène Heitz with the original design still seems to me the soundest option. In particular, Arsène Heitz himself, in 1987, laid claim to his own role in designing the flag and to its religious inspiration when he said that 'the flag of Europe is the flag of Our Lady' [Magnificat magazine, 1987] "Secondly, it is worth noting the testimony of Father Pierre Caillon, who refers to a meeting with Arsène Heitz. Caillon tells of having met the former Council of Europe employee by chance in August 1987 at Lisieux in front of the Carmelite monastery. It was Heitz who stopped him and declared 'I was the one who designed the European flag. I suddenly had the idea of putting the 12 stars of the Miraculous Medal of the Rue du Bac on a blue field. My proposal was adopted unanimously on 8 December 1955, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. I am telling you this, Father, because you are wearing the little blue cross of the Blue Army of Our Lady of Fatima'"

- ↑ European Union: Myths on the flag, Flags of the World, 2002 [1995], retrieved 4 August 2007 "While Count Coudenhove-Kalergi in a personal statement maintained that three leading Catholics within the Council had subconsciously chosen the twelve stars on the model of Apocalypse 12:1, Paul M.G. Lévy, Press Officer of the Council from 1949 to 1966, explained in 1989 that there was no religious intention whatsoever associated with the choice of the circle of twelve stars." Peter Diem, 11 June 2002

- ↑ According to an Der Sternenkranz ist die Folge eines Gelübdes, Die Welt, 26 August 1998.

- ↑ L'origine chrétienne du drapeau européen (in French), atheisme.org, retrieved 21 January 2009

- ↑ Congrégation Mariale des Hommes (in French), Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Strasbourg, 4 February 2004, retrieved 24 January 2009

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Flag of the European Union. |

- Council of Europe on the flag

- EU's graphical specifications for the flag

- The symbols of the European Union : The flag of the Council Europe. Collection. Centre for European Studies - CVCE (Previously European NAvigator)

- Ceremony to mark the expiry of the ECSC Treaty (Brussels, 23 July 2002)), Video from The European Commission Audiovisual Library.

- CIA page

- European Union at Flags of the World

- Memorandum on design and designer of European flag

- World flag database

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)