United States Disciplinary Barracks

| |

| Location | Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°22′42″N 94°56′07″W / 39.37833°N 94.93528°W[1] |

| Status | Operational |

| Security class | Minimum-maximum security, Level III (Maximum Security) |

| Capacity | 515 |

| Population | 440 |

| Opened | 1874, rebuilt in 2002 |

| Managed by | United States Army Corrections Command |

The United States Disciplinary Barracks (or USDB, popularly known as Leavenworth, or the DB) is a military correctional facility[2] located on Fort Leavenworth, a United States Army post in Kansas.

It is one of three major prisons built on Fort Leavenworth property, the others being the federal United States Penitentiary, Leavenworth, four miles (6 km) to the south, and the military Midwest Joint Regional Correctional Facility, which opened on 5 October 2010.[3]

It reports to the United States Army Corrections Command and its commandant usually holds the rank of colonel.

The USDB is the U.S. military's only maximum-security facility that houses male service members convicted at court-martial for violations of the Uniform Code of Military Justice. Only enlisted prisoners with sentences over ten years, commissioned officers, and prisoners convicted of offenses related to national security are confined to the USDB. Enlisted prisoners with sentences under ten years are confined in smaller facilities, such as the nearby Midwest Joint Regional Correctional Facility or the Naval Consolidated Brig at Chesapeake, Virginia. Corrections personnel at the facility are Army Corrections Specialists (MOS 31E) trained at the U.S. Army Military Police school located at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, as well as Marine and Air Force corrections personnel.

Female prisoners are typically incarcerated in the Naval Consolidated Brig, Miramar.[4]

First facility

Originally known as the United States Military Prison, the USDB was established by Act of Congress in 1874. Prisoners were used for the bulk of the construction, which began in 1875 and was completed in 1921. The facility was able to house up to 1,500 prisoners. From 1895 until 1903, prisoners from the USDB were used to construct the nearby United States Penitentiary, Leavenworth[5] until around 400 federal prisoners were moved there to complete the work.

Although work on the two prisons continued at about the same time and they share the same design of a central dome-topped building, the two prisons reflect dramatically different prison concepts.

The original USDB followed the Pennsylvania plan modeling on a layout of the Eastern State Penitentiary where cell blocks radiated out from a central structure. Individual cells were relatively isolated. In contrast, the civilian prison is modeled on the Auburn Correctional Facility in New York reflected a newer concept where prisoners were housed in a large rectangular building where there was a certain amount of communal living.[6]

The original USDB was Fort Leavenworth's biggest and tallest building sitting on top of a hill at the corner of McPherson Avenue and Scott Avenue overlooking the Missouri River. The largest buildings of the original barracks ("The Castle") were torn down in 2004. The old domed building was nicknamed "Little Top" in contrast to the domed federal prison 2 1⁄2 miles (4.0 km) south which was nicknamed the "Big Top".[7] The walls and ten of the buildings in the original location remaining—including Pope Hall—have been converted or are in the process of being converted to other uses at the Fort. The prison's original commandant's house still remains.[8]

The original prison was 12 acres (4.9 ha). The walls were from 16 to 41 feet (4.9 to 12.5 m) high.[9]

In 2002, Gail Dillon of Airman magazine said:

"A visitor would immediately notice the medieval ambiance of this institution – the well-worn native stone and brick walls constructed by long-forgotten inmates when 'hard labor' meant exactly that – have witnessed thousands of inmates' prayers, curses, and pleas over the past 128 years" and that entering the facility was "like stepping back in time or suddenly being part of a kitschy movie set about a prison bust."[10]

Current facility

A new state-of-the-art, 515-bed, USDB became operational in September 2002, replacing the old stone wall and brick castle. It was also moved to a new location on Fort Leavenworth.

The new barracks opened at a cost of $67.8 million and is about a mile north of the original barracks. It is on 51 acres (210,000 m2) on the site of the former USDB Farm Colony and is enclosed by two separate 14-foot (4.3 m) high fences. There are three housing units each of which can accommodate up to 142 prisoners. The units described as "pods" are two-tiered triangular shaped domiciles.[11] The cells in the new facility have solid doors and a window. There are no bars. The new facility is said to be much quieter than the old one and is preferred by inmates.[12] Colonel Colleen L. McGuire, the first female commandant of the USDB, said in 2002 that the new facility is "much more efficient in design and layout – much brighter and lighter."[13]

The new prison reflects current prison design of smaller low-rise separate buildings where prisoners can be more easily isolated from the general population.[6]

In 2009, the Barracks along with the Standish Maximum Correctional Facility in Michigan were being considered for relocation of 220 prisoners from the Guantanamo Bay detention camp. Kansas officials including both U.S. Senators objected to the transfer; Pat Roberts stated that the transfer would require 2,000 privately owned acres around the fort to be acquired for the use of eminent domain to establish a stand-off zone because the prison is on the perimeter of the fort.[14]

Accreditation

The USDB has continuously been accredited from the American Correctional Association (ACA) since 1988. In 2012 the facility received a 100% rating and the accolades of the rating team. Three independent evaluators visited the prison facilities to check on more than 500 standards, including mental health services, safety issues and other aspects of the facility related to humane treatment of inmates. The USDB received a top rating in all of the standards despite having a portion of its staffing deployed to Iraq to oversee detention operations there.[15]

Staffing

The USDB is currently staffed by members of the 15th Military Police Brigade. Many soldiers have a designated military occupational specialty 31E, corrections specialists. They are under Army Corrections Command, which was activated in Washington, D.C. in 2007 under the Provost Marshal General.[16]

Demographics

As of 1988 the prison had 1,450 prisoners, including 21 women. The prison population at the time included 42 officers, with one of them being a lieutenant colonel.[17] Since then all female prisoners have been moved to NAVCONBRIG Miramar.

Cemetery

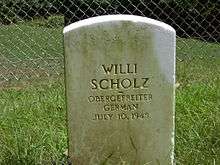

Deceased prisoners who are not claimed by their family members are buried near the original USDB. There were 300 graves dating from between approximately 1894 and 1957, 56 of which are unmarked and 14 more that belong to German prisoners of war executed for the murder of fellow POWs. Before the war with Germany ended, it was feared that American and British prisoners who had killed collaborators in their prison camps would be executed as well. That fear ended when Germany surrendered in May 1945. The executions at Fort Leavenworth were carried out in three groups: Five on 10 July, two on 14 July and seven on 25 August, all in 1945.[18]

Capital punishment

The USDB houses the U.S. military's male death row inmates. Since 1945, there have been 21 executions at the USDB, including fourteen German prisoners of war executed in 1945 for murder.[19] The last execution by the U.S. Military was the hanging of Army PFC John A. Bennett, on 13 April 1961, for the rape and attempted murder of an 11-year-old Austrian girl.[20] Bennett's execution took place four years after it was approved by President Dwight D. Eisenhower and then his successor President John F. Kennedy. Bennett applied to Kennedy for a Stay of Execution after an appeal to him from the Austrian victim and her parents for the African American soldier. This was promptly denied by the White House.[21] All executions at the USDB thus far have been by hanging, but lethal injection has been specified as the military's current mode of execution. As of 29 August 2013, there are six inmates on death row at the USDB, the most recent addition being Nidal Hasan, sentenced to death on 28 August 2013. Andrew P. Witt is currently the only Air Force member on the USDB death row.[22]

The execution of Army PVT Ronald A. Gray, who has been on military death row since 1988, was approved by President George W. Bush on 28 July 2008. Gray was convicted of the rape, two murders and an attempted murder of three women, two of them Army soldiers and the third a civilian taxi driver whose body was found on the post at Fort Bragg.[23] On 26 November 2008, a federal judge granted Gray a stay of execution to allow time for further appeals.[24]

Within the prison, Death Row is located in an isolated corridor away from other inmates.[25]

Notable inmates

Current notable inmates

Death row

- Hasan Akbar[25] – Killed two officers and wounded 14 others while deployed to Camp Pennsylvania, Kuwait on the eve of the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

- Nidal Hasan – Killed 12 soldiers (including one who was pregnant) and one civilian, and wounded more than 30 others during the 2009 Fort Hood shooting.[26]

Non-death row

- Robert Bales – Killed 16 Afghan civilians (including nine children) and wounded six others in Afghanistan during the Kandahar massacre. Bales agreed to a plea deal during his court-martial in order to avoid the death penalty and is currently serving a life sentence.[27]

- Chelsea Manning[28] – Unlawfully downloaded and disseminated thousands of classified documents and several classified videos to the website WikiLeaks while known as Bradley Manning. Manning was sentenced to 35 years of confinement.[29]

Former notable inmates

- Jonathan Wells – Author who wrote Icons of Evolution. Previously drafted into the Army for two years during the Vietnam War, he publicly refused to report for Reserve duty while attending college at the University of California, Berkeley. Wells was sentenced to 18 months of confinement.[30]

- William Calley – Convicted for his part in the My Lai Massacre.[31] Originally given a life sentence, President Richard Nixon ordered the Army to transfer him from Fort Leavenworth to house arrest in Fort Benning one day after he was sentenced.

- Charles Graner – Convicted of prisoner abuse in connection with the 2003–2004 Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse scandal. Graner was sentenced to ten years of confinement and was released on parole after serving six and a half years of his sentence.[32]

Incidents

- 1918 – Joseph and Michael Hofer, two Christian pacifists who were drafted to serve in World War I, died at Fort Leavenworth after refusing to enlist or wear uniforms. They were held in solitary confinement, beaten, and starved to death.[33]

- 17 August 1988 – Inmate David Newman escaped after hiding in Pope Hall while on Wood Shop Detail. He assembled a ladder, kicked out a window and climbed over the wall between Towers 3 and 4. He was captured four days later in Kansas City. Following the escape, bars were placed on the windows of all buildings within the complex and interior chain link with razor wire top guard was placed between the buildings and the exterior stone walls.[34]

- 12 May 1995 – 300 inmates refused lockdown in the old prison. The uprising was put down by 150 correction officers.[35]

- 12 August 2010 – Two inmates overpowered a correction officer in the Special Housing Unit. They then were joined by 11 others. A special tactics unit took control of the Special Housing Unit and freed the guard. Several inmates and one rescuer sustained non-life-threatening injuries in the incident. This was the first such incident in the new prison.[35]

In popular culture

- From Here to Eternity is the 1951 James Jones novel and 1953 film. First Sergeant Milton Warden tells Mrs. Karen Holmes, wife of his commanding officer Captain Dana Holmes, "He (Warden) risks twenty years in Leavenworth, for his affair with her."

- The Last Castle is a 2001 drama film directed by Rod Lurie, starring Robert Redford and James Gandolfini, which portrays a struggle between inmates and the warden of the United States Disciplinary Barracks.

- xXx: State of the Union is a 2005 action film, directed by Lee Tamahori, starring Ice Cube, Willem Dafoe and Samuel L. Jackson.

- Attack 1956 WWII film with Jack Palance, Col. Bartlett Lee Marvin threatens cowardly Capt. Cooney Eddie Albert if he abandons his company's position under attack, stating "I'll hound you right into Leavenworth."

- The Escape the 2014 David Baldacci fictional novel. The experienced military investigator John Puller is asked to help find his older brother, who was convicted of national security crimes and mysteriously escaped from USDB.

In Lee Child's novel Persuader, several villains are noted as former inmates of Fort Leavenworth

Gallery

View of the USDB – Note date above double doors – 1877.

View of the USDB – Note date above double doors – 1877. Headstone of a German prisoner.

Headstone of a German prisoner. Prison cell.

Prison cell.

See also

- List of individuals executed by the United States military

- List of U.S. military prisons

- Penal military unit#United States

References

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: United States Disciplinary Barracks

- ↑ U.S.D.B Home - 15 December 2013

- ↑ Army Corrections Command stands up – Fort Leavenworth Lamp -19 October 2007

- ↑ Powers, Rod. "Inside a Military Prison. About.com. Retrieved on January 27, 2014. "dditionally, all female prisoners within DOD serve their time at NAVCONBRIG Miramar to better facilitate the rehabilitative process. "

- ↑ Named for Henry Leavenworth

- 1 2 The U.S. Federal Prison System by Mary F. (Francesca) Bosworth – Sage Publications, Inc; 1st edition (15 July 2002) ISBN 0-7619-2304-7

- ↑

- ↑ ACT_moves to new digs in old USDB – Fort Leavenworth Lamp – 9 July 2009

- ↑ Saga of Fort Leavenworth Castle, Donald Jay Olsen, page 10.

- ↑ Dillon, Gail (2002-10). "Crime and punishment: inside Fort Leavenworth's historic U.S. Disciplinary Barracks." Airman, November 2002. 1. Retrieved on 2010-03-06 from http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0IBP/is_11_46/ai_94206954/.

- ↑ Title: Part C – The United States Disciplinary Barracks

- ↑ "CJONLINE.com Article on the USDB".

- ↑ Dillon, Gail. "Crime and punishment: inside Fort Leavenwoth's historic U.S. Disciplinary Barracks." Airman. November 2002. 2. Retrieved on 6 March 2010.

- ↑ Gitmo detainees should not come to Leavenworth – Pat Roberts – Kansas City Star – 8 August 2009

- ↑ Fort Leavenworth Lamp newspaper article "JCRF, USDB attain 100 percent scores for accreditations" 15 March 2012 http://www.army.mil/article/75838/JRCF__USDB_attain_100_percent_scores_for_accreditations/

- ↑ http://www.aca.org/fileupload/177/ahaidar/Miller.pdf

- ↑ "Ft. Leavenworth's Military Inmates Get Grim Home Where Discipline Is Order of Day." Los Angeles Times. December 4, 1988. Retrieved on July 10, 2016.

- ↑ Fort Leavenworth Military Prison Cemetery from Interment.net

- ↑ List of U.S. Military Executions from the Death Penalty information Center

- ↑ Soldier dies on the gallows for attack on small child

- ↑ http://articles.latimes.com/1994-07-12/news/mn-14826_1_black-soldier

- ↑ The U.S. Military Death Penalty from the Death Penalty information Center

- ↑ Execution by Military Is Approved by President

- ↑ First Military Execution in 50 Years Delayed

- 1 2 Goldman, Russell. "Fort Hood Shooter Could Join 5 Others on Death Row." ABC News. 13 November 2009. 1. Retrieved on 21 October 2010.

- ↑ "Hasan arrives at U.S. Disciplinary Barracks"

- ↑ "Bales arrives at USDB"

- ↑ Londoño, Ernesto. "Convicted leaker Bradley Manning changes legal name to Chelsea Elizabeth Manning". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- ↑ Manning arrives at Fort Leavenworth prison ""

- ↑ Wells, Jonathan. The Politically Incorrect Guide to Darwinism and Intelligent Design. Regnery Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59698-013-6.

- ↑ http://www.strategypage.com/militaryforums/512-33690.aspx

- ↑ CNN Wire Staff. "Notorious Abu Ghraib guard released from prison." CNN. 6 August 2011. Retrieved on 6 August 2011.

- ↑ Hostetler, John Andrew. 'The Hutterites in North America'. Brooks/Cole, 2002.

- ↑ http://arba.army.pentagon.mil/documents/Vanguard%20Vol%203.pdf

- 1 2 http://www.military.com/news/article/mutinied-leavenworth-inmates-face-more-time.html Archived 15 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States Disciplinary Barracks. |

- U.S. Disciplinary Barracks Official Website