Fort William Henry

Coordinates: 43°25′13″N 73°42′40″W / 43.42028°N 73.71111°W

| Fort William Henry | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Fort |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Great Britain, New France |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1755 |

| In use | 1755–1757 |

| Battles/wars | French and Indian War |

Fort William Henry was a British fort at the southern end of Lake George in the province of New York. It is best known as the site of notorious atrocities committed by the Huron tribes against the surrendered British and provincial troops following a successful French siege in 1757, an event portrayed in James Fenimore Cooper's novel, The Last of the Mohicans, first published in January 1826.

The fort's construction was ordered by Sir William Johnson in September 1755, during the French and Indian War, as a staging ground for attacks against the French fort at Crown Point called Fort St. Frédéric. It was part of a chain of British and French forts along the important inland waterway from New York City to Montreal, and occupied a key forward location on the frontier between New York and New France. It was named for both Prince William, the Duke of Cumberland, the younger son of King George II, and Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester, a grandson of King George II and a younger brother of the future King George III.[1]

Following the 1757 siege, the French destroyed the fort and withdrew. While other forts were built nearby in later years, the site of Fort William Henry lay abandoned. In the 19th century, it was a destination for tourists. In the 1950s interest in the history of the site revived, and a replica of the fort was constructed. It is now operated as a living museum and a popular tourist attraction in the village of Lake George.

Construction

In 1755, Sir William Johnson, British Indian Supervisor of the Northeast, established a military camp at the southern end of Lake George, with the objective of launching an attack on Fort St. Frédéric, a French fort at Crown Point on Lake Champlain. The French commander, Baron Dieskau, decided to launch a preemptive attack on Johnson's support base at Fort Edward on the Hudson River. Their movements precipitated the somewhat inconclusive Battle of Lake George on September 8, 1755, part of which was fought on the ground of Johnson's Lake George camp. Following the battle, Johnson decided to construct a fortification near the site, while the French began construction of Fort Carillon near the northern end of the lake.

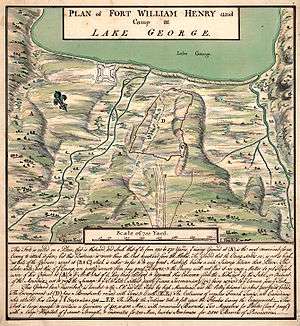

Design and construction of the new fortification was overseen by British military engineer William Eyre of the 44th Foot. Fort William Henry was an irregular square fortification with bastions on the corners, in a design that was intended to repel Indian attacks, but not necessarily withstand attack from an enemy armed with artillery. Its walls were 30 feet (9.1 m) thick, with log facings around an earthen filling. Inside the fort were wooden barracks two stories high, built around the parade ground. Its magazine was in the northeast bastion, and its hospital was located in the southeast bastion. The fort was surrounded on three sides by a dry moat, with the fourth side sloping down to the lake. The only access to the fort was by a bridge across the moat.[2] The fort could house 400 to 500 men; additional troops were quartered in an entrenched camp 750 yards (690 m) southeast of the fort, near the site of the 1755 Battle of Lake George.[3]

Occupation

The fort was ready for occupancy, if not fully complete, on November 13, 1755. Eyre served as its first commander, with a garrison consisting of companies from his 44th, as well as several companies of Rogers' Rangers.[4]

In the spring of 1757, command of the fort was turned over to George Monro, with a garrison principally drawn from the 35th Foot and the 60th (Royal American) Foot.[5] By June the garrison had swollen to about 1,600 men with the arrival of provincial militia companies from Connecticut and New Jersey. Because the fort was too small to quarter this many troops, many of them were stationed in Johnson's old camp to the southwest of the fort. When word arrived in late July that the French had mobilized to attack the fort, another 1,000 regulars and militia arrived, swelling Monro's force to about 2,300 effective troops.[6] Johnson's camp, where many were quartered, was quickly protected by the digging of trenches. Conditions in both the fort and the camp were not good, and many men were ill, including some with smallpox.

Siege

The French force of General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm arrived on August 3, and established camps to the south and west of the fort. Following heavy bombardment and siege operations that progressively neared the fort's walls, the garrison was forced to surrender on August 8th when it became apparent that General Daniel Webb, the commander at Fort Edward, was not sending any relief.[7] French forces totaled some 8,000, consisting of 3,000 regulars, 3,000 militia and nearly 2,000 Native Americans from various tribes.[6]

Massacre

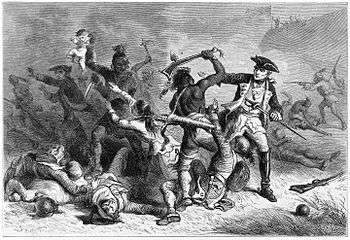

What happened next has been described in historical and popular treatments as a massacre. While horrific actions took place, the number of people killed and wounded appears to have been relatively modest; historian Ian Steele claims that it is unlikely that more than 200 people (about 7.5% of the captured population) were killed or wounded.[8]

The terms of surrender were that the British and their camp followers would be allowed to withdraw, under French escort, to Fort Edward, with the full honours of war, on condition that they refrain from participation in the war for 18 months. They were allowed to keep their muskets but no ammunition, and a single symbolic cannon. In addition, British authorities were to release French prisoners within three months.[9]

Montcalm, before agreeing to these terms, attempted to make sure that his Indian allies understood them, and that the chiefs would undertake to restrain their men. The British garrison was then evacuated from the fort to the entrenched camp, while Monro was quartered in the French camp. The Indians then entered the fort and plundered it, butchering some of the wounded and sick that the British had left behind.[9] The French guards posted around the entrenched camp were somewhat unsuccessful at keeping the Indians out of that area, and it took significant effort to prevent plunder and scalping in that camp. Montcalm and Monro initially planned to march the prisoners south the following morning, but after seeing the Indian bloodlust, decided to attempt the march that night. When the Indians became aware that the camp was getting ready to move, a large number of them massed around the camp, causing the leaders to call off the idea.[9]

The next morning, even before the British column began to form up for the march to Fort Edward, the Indians renewed attacks on the largely defenceless British. At 5 am, Indians entered huts in the fort housing wounded British who were supposed to be under the care of French doctors, and killed and scalped them.[10] Monro complained that the terms of capitulation had in essence been violated already, but his contingent was forced to surrender some of its baggage in order to even be able to begin the march. As they marched off, they were harassed by the swarming Indians, who snatched at them, grabbing for weapons and clothing, and pulling away with force those that resisted their actions, including many of the women, children, and black servants.[10] As the last of the men left the encampment, a war whoop sounded, and warriors seized a number of men at the rear of the column.[10]

While Montcalm and other French officers tried to stop these attacks, others did not, and explicitly refused further protection to the British. At this point, the column dissolved, as some prisoners tried to escape the Indian onslaught, while others actively tried to defend themselves. Massachusetts Colonel Joseph Frye reported that he was stripped of much of his clothing and repeatedly threatened. He fled into the woods, and did not reach Fort Edward until August 12, three days later.[11]

Estimates of the numbers captured, wounded or killed varied widely. Ian Steele has compiled estimates ranging from 200 to 1,500.[12] His detailed reconstruction of the action and its aftermath indicates that the final tally of missing and dead ranges from 69 to 184, at most 7.5% of the 2,308 who surrendered.[8]

Atrocities described in accounts of the massacre include the killing and scalping of sick and wounded individuals, and the digging up graves to take additional trophies from those who died of wounds or disease during the siege. As a result, many Indians who participated in the action may have contracted smallpox, which they carried back to their communities.[13] Nester makes no such claim in his book. Neither does Steele.

After the battle, the French systematically destroyed the fort before returning to Fort Carillon.[14]

Reconstruction

After the French won the battle, the French destroyed the fort. It lay abandoned for 200 years. Reconstruction of a replica of the fort took place in the 1950s.

In 1992 a replica of Fort William Henry was constructed on Lake James (a large reservoir in the mountains of Western North Carolina that straddles the border between Burke and McDowell counties) to serve as a filming site for the Daniel Day-Lewis movie, The Last of the Mohicans.

References

- Notes

- ↑ For information on the name of the fort, see Anderson, p. 123

- ↑ Starbuck, p. 6

- ↑ Starbuck, p. 7

- ↑ Starbuck, p. 8

- ↑ Nester, p. 55

- 1 2 Nester, p. 56

- ↑ The siege is recounted in e.g. Nester, pp. 56–59

- 1 2 Steele, p. 144

- 1 2 3 Nester, p. 59

- 1 2 3 Nester, p. 60

- ↑ Dodge, p. 92

- ↑ Nester, p. 62

- ↑ Nester, p. 61

- ↑ Nester, p. 64

- Sources

- Anderson, Fred (2000). Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754 to 1766. New York: Vintage Books.

- Brooks, Victor (1999). The Boston Campaign. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing. ISBN 1-58097-007-9. OCLC 42581510.

- Chidsey, Donald Barr (1966). The Siege of Boston. Boston, MA: Crown. OCLC 890813.

- Dodge, Edward J (1998). Relief is greatly wanted: the battle of Fort William Henry. Heritage Books. ISBN 978-0-7884-0932-5.

- Nester, William R (2000). The first global war: Britain, France, and the fate of North America, 1756–1775. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-96771-0.

- Starbuck, David (2002). Massacre at Fort William Henry. UPNE. ISBN 978-1-58465-166-6.

- Steele, Ian K (1990). Betrayals: Fort William Henry & the 'Massacre'. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505893-3.

External links

- An Account of the Two Attacks on Fort William Henry 1757

- Fort William Henry massacre

- Fort William Henry Museum

- Lake George Historical Association

- History of the 35th Foot