Free Soil Party

Free Soil Party | |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1848 |

| Dissolved | 1854 |

| Merger of | Liberty Party, Barnburner Democrats, Conscience Whigs |

| Merged into | Republican Party |

| Ideology | Anti-slavery expansion |

| International affiliation | None |

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived political party in the United States active in the 1848 and 1852 presidential elections, and in some state elections. Founded in Buffalo, New York, it was a third party and a single-issue party that largely appealed to and drew its greatest strength from New York State. The party leadership consisted of anti-slavery former members of the Whig Party and the Democratic Party. Its main purpose was to oppose the expansion of slavery into the western territories, arguing that free men on free soil comprised a morally and economically superior system to slavery. It opposed slavery in the new territories (agreeing with the Wilmot Proviso) and sometimes worked to remove existing laws that discriminated against freed African Americans in states such as Ohio. It nominated Martin Van Buren for the presidency in 1848 and John P. Hale for the presidency in 1852.

The party membership was largely absorbed by the Republican Party between 1854 and 1856, by way of the Anti-Nebraska movement.

Positions

Free Soil candidates ran on a platform that declared: "...we inscribe on our banner, 'Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor and Free Men,' and under it we will fight on and fight ever, until a triumphant victory shall reward our exertions." The party also called for a tariff for revenue only (i.e. import taxes sufficient to meet federal government expenses without creating protectionist trade barriers), and for a homestead act. The Free Soil Party's main support came from areas of Ohio, upstate New York and western Massachusetts, although other northern states also had representatives. The party contended that slavery undermined the dignity of labor and inhibited social mobility, and was therefore fundamentally undemocratic. Viewing slavery as an economically inefficient, obsolete institution, Free Soilers believed that slavery should be contained, and that if contained it would ultimately disappear.

History

In 1848 the New York State Democratic convention did not endorse the Wilmot Proviso, an act that would have banned slavery in any territory conquered by the United States in the Mexican War. Almost half the members, known as "Barnburners", walked out after denouncing the national platform. Lewis Cass, the Democratic Party's 1848 presidential nominee, supported popular sovereignty (local control) for determining the status of slavery in the U.S. territories. This stance repulsed the New York State Democrats and encouraged them to join with anti-slavery Conscience Whigs and the majority of the Liberty Party to form the Free Soil Party, which was formalized in the summer of 1848 at conventions in Utica and Buffalo. The Free Soilers nominated former Democratic President Martin Van Buren for president, along with Charles Francis Adams for vice president, at Lafayette Square in Buffalo, then known as Court House Park.[1] The main party leaders were Salmon P. Chase of Ohio and John P. Hale of New Hampshire. The Free Soil candidates won 10% of the popular vote in 1848 but no electoral votes, in part because the nomination of Van Buren discouraged many anti-slavery Whigs from supporting them.

The party distanced itself from abolitionism and avoided the moral problems implicit in slavery. Members emphasized instead the threat slavery would pose to free white labor and northern businessmen in the new western territories. Although abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison derided the party philosophy as "white manism,"[2] the approach appealed to many moderate opponents of slavery. The 1848 platform pledged to promote limited internal improvements, work for a homestead law, work towards paying off the public debt, and introduce a moderate tariff for revenue only.

The Compromise of 1850 temporarily neutralized the issue of slavery and undercut the party's no-compromise position. Most Barnburners returned to the Democratic Party while most of the Conscience Whigs returned to the Whig Party. This resulted in the Free Soil Party becoming dominated by ardent anti-slavery leaders.

The party ran John P. Hale in the 1852 presidential election, but its share of the popular vote shrank to less than 5%. However two years later, after enormous outrage over the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854, the remains of the Free Soil Party helped form the Republican Party.[3]

Legacy

The Free Soil Party sent two Senators and fourteen Representatives to the thirty-first Congress, which convened from March 4, 1849 to March 3, 1851. Since there were party members on the floor of Congress, they could carry far more weight in the government and in the debates that took place. The Free Soil Party presidential nominee in 1848, Martin Van Buren, received 291,616 votes against Zachary Taylor of the Whigs and Lewis Cass of the Democrats, but Van Buren received no electoral votes. The party's "spoiler effect" in 1848 may have helped Taylor into office in a narrowly contested election.

The strength of the party, however, was its representation in Congress. The sixteen elected officials had influence far beyond their numerical strength. The party's most important legacy was as a route for anti-slavery Democrats to join the new Republican coalition.

In August 1854 an alliance was brokered at Ottawa, Illinois between the Free Soil Party and the Whigs (in part based on the efforts of local newspaper publisher Jonathan F. Linton) that gave rise to the Republican Party.[4]

Free Soil Township, Michigan was named after the Free Soil party in 1848.[5]

Presidential candidates

| Year | Presidential candidate | Vice Presidential candidate | Won/Lost |

|---|---|---|---|

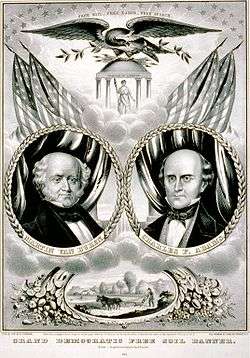

| 1848 | Martin Van Buren | Charles Francis Adams | Lost |

| 1852 | John P. Hale | George W. Julian | Lost |

Other noted Free Soilers

- Jonathan Blanchard, president of Knox College[6]

- Walter Booth, U.S. Congressman from Connecticut

- David C. Broderick, U.S. Senator from California

- William Cullen Bryant

- Salmon P. Chase, U.S. Senator from Ohio

- Oren B. Cheney, legislator from Maine, founder of Bates College

- Richard Henry Dana, Jr.

- Sidney Edgerton, U.S. Congressman from Ohio, Chief Justice of the Idaho Territorial Supreme Court and Territorial Governor of Montana

- John C. Frémont, U.S. Senator from California

- Leander F. Frisby, Wisconsin Attorney General

- Joshua Reed Giddings, U.S. Congressman from Ohio

- Francis Gillette, U.S. Senator from Connecticut

- James Harlan, U.S. Senator from Iowa

- Thomas Hoyne, future Mayor of Chicago[6]

- Horace Mann, U.S. Congressman from Massachusetts and educational reformer

- J. Young Scammon, Chicago pioneer and state Whig leader, who in 1848 ran on a "Free Soil plank" in the 4th Congressional District[7]

- William B. Ogden, former Mayor of Chicago and president of the Galena and Chicago Union Railroad[6]

- Charles Sumner, U.S. Senator from Massachusetts

- Walt Whitman, member of the Free Soil Committee for Brooklyn and editor of the Brooklyn Freeman, a Free Soil newspaper

- John Greenleaf Whittier

- Henry Wilson

- Asa Walker

- Victor Willard, Wisconsin State Senator, 17th District, 1849–50; and Wisconsin Constitutional Convention Delegate, 1846 (Dem.)[8]

- Willard Woodard, educator, publisher, Free Soil club co-founder and president

See also

- Second Party System

- Origins of the American Civil War

- Appeal of the Independent Democrats

- Anti-Nebraska movement

References

- ↑ "Old Court House". History of Buffalo. Chuck LaChiusa. Archived from the original on August 8, 2007. Retrieved March 8, 2008.

- ↑ Alcott, L.M.; Elbert, S. (1997). Louisa May Alcott on Race, Sex, and Slavery. Northeastern University Press. ISBN 9781555533076.

- ↑ Mayfield, John; Rehearsal for Republicanism: Free Soil and the Politics of Anti-Slavery; Port Washington. NY; Kennikat, 1980

- ↑ Taylor, William Alexander (1909). "Centennial history of Columbus and Franklin County, Ohio; Vol. 2". S. J. Clarke Publishing Co. pp. 161–162. Archived from the original on January 20, 2009.

- ↑ Boughner, Eliane Durnin (Jun 25, 1981). "Free Soil Gets History Write-up". Ludington Daily News. Ludington, MI. Retrieved Sep 13, 2016.

- 1 2 3 The Past and Present of Kane County, Illinois. Chicago, IL: William Le Baron, Jr. & Co. 1878. p. 258.

- ↑ Harris, Norman Dwight (1904). The History of Negro Servitude in Illinois. pp. 173–174. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ The Blue Book of the State of Wisconsin for 1879; Waukesha Democrat (newspaper), December 5, 1848; Watertown Chronicle, December 5, 1849

Further reading

- Frederick J. Blue, Salmon P. Chase: A Life in Politics (1987)

- Frederick J. Blue, The Free Soilers: Third Party Politics, 1848-54 (1973)

- Corey M. Brooks, Liberty Power: Antislavery Third Parties and the Transformation of American Politics (University of Chicago Press, 2016). 302 pp.

- Martin Duberman, Charles Francis Adams, 1807–1886 (1968)

- Jonathan Halperin Earle, Jacksonian Antislavery and the Politics of Free Soil, 1824–1854 (2004)

- Foner, Eric (1995) [Originally published 1970]. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509497-2.

- T. C. Smith, Liberty and Free Soil Parties in the Northwest (New York, 1897)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Free Soil Party. |

- Free Soil Banner - Indianapolis Marion County Public Library

- American Abolitionists and Antislavery Activists, comprehensive list of abolitionist and anti-slavery activists and organizations in the United States, including the Free Soil Party; website includes historic biographies and anti-slavery timelines, bibliographies, etc.

-

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Free-Soil Party". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "Free Soil Party". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Free-Soil Party, The". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

.svg.png)