Frequency mixer

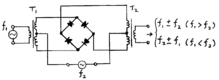

In electronics, a mixer, or frequency mixer, is a nonlinear electrical circuit that creates new frequencies from two signals applied to it. In its most common application, two signals at frequencies f1 and f2 are applied to a mixer, and it produces new signals at the sum f1 + f2 and difference f1 − f2 of the original frequencies, called heterodynes. Other frequency components may also be produced in a practical frequency mixer.

Mixers are widely used to shift signals from one frequency range to another, a process known as heterodyning, for convenience in transmission or further signal processing. For example, a key component of a superheterodyne receiver is a mixer used to move received signals to a common intermediate frequency. Frequency mixers are also used to modulate a carrier signal in radio transmitters.

Types

The essential characteristic of a mixer is that it produces a component in its output which is the product of the two input signals. A device that has a non-linear (e.g. exponential) characteristic can act as a mixer. Passive mixers use one or more diodes and rely on the non-linear relation between voltage and current to provide the multiplying element. In a passive mixer, the desired output signal is always of lower power than the input signals.

Active mixers use an amplifying device (such as a transistor or vacuum tube) to increase the strength of the product signal. Active mixers improve isolation between the ports, but may have higher noise and more power consumption. An active mixer can be less tolerant of overload.

Mixers may be built of discrete components, may be part of integrated circuits, or can be delivered as hybrid modules.

Mixers may also be classified by their topology:

- An unbalanced mixer, in addition to producing a product signal, allows both input signals to pass through and appear as components in the output.

- A single balanced mixer is arranged with one of its inputs applied to a balanced (differential) circuit so that either the local oscillator (LO) or signal input (RF) is suppressed at the output, but not both.

- A double balanced mixer has both its inputs applied to differential circuits, so that neither of the input signals and only the product signal appears at the output.[1] Double balanced mixers are more complex and require higher drive levels than unbalanced and single balanced designs.

Selection of a mixer type is a trade off for a particular application.

Mixer circuits are characterized by their properties such as conversion gain (or loss), and noise figure.[2]

Nonlinear electronic components that are used as mixers include diodes, transistors biased near cutoff, and at lower frequencies, analog multipliers. Ferromagnetic-core inductors driven into saturation have also been used. In nonlinear optics, crystals with nonlinear characteristics are used to mix two frequencies of laser light to create optical heterodynes.

Diode

A diode can be used to create a simple unbalanced mixer. This type of mixer produces the original frequencies as well as their sum and their difference. The significant property of the diode here is its non-linearity (or non-Ohmic behavior), which means its response (current) is not proportional to its input (voltage). The diode therefore does not reproduce the frequencies of its driving voltage in the current through it, which allows the desired frequency manipulation. The current I through an ideal diode as a function of the voltage V across it is given by

where what is important is that V appears in e's exponent. The exponential can be expanded as

and can be approximated for small x (that is, small voltages) by the first few terms of that series:

Suppose that the sum of the two input signals is applied to a diode, and that an output voltage is generated that is proportional to the current through the diode (perhaps by providing the voltage that is present across a resistor in series with the diode). Then, disregarding the constants in the diode equation, the output voltage will have the form

The first term on the right is the original two signals, as expected, followed by the square of the sum, which can be rewritten as , where the multiplied signal is obvious. The ellipsis represents all the higher powers of the sum which we assume to be negligible for small signals.

Suppose that two input sinusoids of different frequencies are fed into the diode, such that and . The signal becomes:

Expanding the square term yields:

Ignoring all terms except for the term and utilizing the prosthaphaeresis (product to sum) identity,

yields,

demonstrating how new frequencies are created from the mixer.

Switching

Another form of mixer operates by switching, with the smaller input signal being passed inverted or non inverted according to the phase of the local oscillator (LO). This would be typical of the normal operating mode of a packaged double balanced mixer, with the local oscillator drive considerably higher than the signal amplitude.

The aim of a switching mixer is to achieve linear operation over the signal level by means of hard switching driven by the local oscillator. Mathematically the switching mixer is not much different from a multiplying mixer, just because instead of the LO sine wave term we would use the signum function. In the frequency domain the switching mixer operation leads to the usual sum and difference frequencies, but also to further terms e.g. ±3fLO, ±5fLO, etc. The advantage of a switching mixer is that it can achieve (with the same effort) a lower noise figure (NF) and larger conversion gain. This is because the switching diodes or transistors act either like a small resistor (switch closed) or large resistor (switch open), and in both cases only a minimal noise is added. From the circuit perspective, many multiplying mixers can be used as switching mixers, just by increasing the LO amplitude. So RF engineers simply talk about mixers and mean switching mixers.

The mixer circuit can be used not only to shift the frequency of an input signal as in a receiver, but also as a product detector, modulator, phase detector or frequency multiplier.[3] For example, a communications receiver might contain two mixer stages for conversion of the input signal to an intermediate frequency and another mixer employed as a detector for demodulation of the signal.

See also

- Frequency multiplier

- Subharmonic mixer

- Product detector

- Pentagrid converter

- Beam deflection tube

- Ring modulation

- Gilbert cell

- Optical heterodyne detection

- Intermodulation

- Third-order intercept point

- Rusty bolt effect

References

- ↑ Poole, Ian. "Double balanced mixer tutorial". Adrio Communications. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ D.S. Evans, G. R. Jessop, VHF-UHF Manual Third Edition, Radio Society of Great Britain, 1976, page 4-12

- ↑ Paul Horowitz, Winfred Hill The Art of Electronics Second Edition, Cambridge University Press 1989, pp. 885–887.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Radio electronic diagrams. |

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document "Federal Standard 1037C".

This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document "Federal Standard 1037C".