Fritz Haarmann

| Fritz Haarmann | |

|---|---|

|

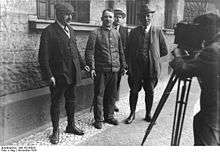

Mug shot of Fritz Haarmann, taken after his arrest in June 1924 | |

| Born |

Friedrich Heinrich Karl Haarmann 25 October 1879 Hanover, German Empire |

| Died |

15 April 1925 (aged 45) Hanover, Weimar Republic |

| Cause of death | Decapitation by guillotine |

| Other names |

The Butcher of Hanover The Wolf Man The Vampire of Hanover |

| Criminal charge | 27 murders |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Conviction(s) | 24 murders |

| Killings | |

| Victims | 24-27+ |

Span of killings | 25 September 1918–14 June 1924 |

| Country | Germany |

| State(s) | Province of Hanover, Prussia |

Date apprehended | 22 June 1924 |

Friedrich Heinrich Karl "Fritz" Haarmann (25 October 1879 – 15 April 1925) was a German serial killer, known as the Butcher of Hanover and the Vampire of Hanover, who committed the sexual assault, murder, mutilation and dismemberment of a minimum of 24 boys and young men between 1918 and 1924 in Hanover, Germany.

Described by the judge at his trial as being "forever degraded as a citizen," Haarmann was found guilty of 24 of the 27 murders for which he was tried and sentenced to death by beheading in December 1924.[1] He was subsequently executed in April 1925.

Haarmann became known as the Butcher of Hanover (German: Der Schlächter von Hannover) due to the extensive mutilation and dismemberment committed upon his victims' bodies and by such titles as the Vampire of Hanover (der Vampir von Hannover) and the Wolf Man (Wolfsmensch) because of his preferred murder method of biting into or through his victims' throats.

Early life

Childhood

Friedrich Heinrich Karl "Fritz" Haarmann was born in Hanover on 25 October 1879, the sixth and youngest child born to Johanna (née Claudius) and Ollie Haarmann.[2] Haarmann's father had little time for his children, whereas his mother spoiled her youngest child.[3]

Reportedly, Haarmann's father had married his mother (who was seven years his senior) on account of her wealth. Haarmann Sr. was known to be an argumentative, short-tempered individual who conducted several affairs throughout the duration of his marriage. From his early childhood, Fritz developed a bitter hatred and rivalry towards his father, which would continue until his father's death in 1921.

Fritz was a quiet child, with few friends his own age or gender and who seldom socialized with any children other than his siblings outside of school. From an early age, Haarmann's behavior was noticeably effeminate: he was known to shun boys' activities and instead play with his sisters' dolls[4] and dress in their clothes. He also developed a passion for both needlework and cookery.

In 1886, Haarmann began his schooling, where he was noted by teachers to be a spoiled and mollycoddled child who was prone to daydreaming. Although his behavior at school was noted to be exemplary, his academic performance was below average and on two occasions, Haarmann had to repeat a school year. On one occasion when he was approximately eight years old,[5] Haarmann was molested by one of his teachers, although he would never discuss this incident in detail.

Despite his effeminate traits, Haarmann grew into a trim, physically strong youth. With his parents' consent, he finished his schooling in 1894. Upon leaving school, he briefly obtained employment as an apprentice locksmith before opting, at age 15, to enroll in a military academy in the town of Breisach.[3] His military training began on 4 April 1895.

Adolescence and first offenses

Haarmann initially adapted to military life, and performed well as a trainee soldier; however, after five months of military service, he began to suffer periodic lapses of consciousness which would be diagnosed as being "equivalent to epilepsy" in October 1895. The following month, Haarmann discharged himself from the military and returned to Hanover, where he briefly worked in his father's cigar factory.

At the age of 16, Haarmann committed his first known sexual offenses; all of which involved young boys whom he would lure to secluded areas—typically cellars—before proceeding to sexually abuse them. He was first arrested for offenses of this nature in July 1896. Following further offenses of this nature, the Division for Criminal Matters opted to place Haarmann in a mental institution in the city of Hildesheim. Although briefly transferred to a Hanover hospital for psychiatric evaluation, he would be certified as "incurably deranged,"[6] and unfit to stand trial by a psychologist named Gurt Schmalfuss. Schmalfuss ordered Haarmann to be confined at the mental institution indefinitely. Haarmann was returned to the mental institution on 28 May 1897.

Seven months later, Haarmann escaped the mental institution. With apparent assistance from his mother, Haarmann fled to Zürich, Switzerland, where he worked for 16 months before he returned to Hanover in April 1899. Early the following year, Haarmann became engaged to a woman named Erna Loewert,[7] who soon became pregnant with his child. (Haarmann's fiancée would later arrange for her first pregnancy to be aborted.) In October 1900, Haarmann received notification to perform his compulsory military service.

Military service

On 12 October 1900, Haarmann was deployed to the Alsatian city of Colmar to serve in the Number 10 Rifle Battalion. Throughout his service, Haarmann earned a reputation amongst his superiors as an exemplary soldier and excellent marksman, and he would later describe his period of service with this battalion as being the happiest of his entire life. After collapsing while on exercise with his battalion in October 1901, Haarmann began to suffer dizzy spells, and was subsequently hospitalized for over 4 months. He was later deemed "unsuitable for [military] service and work" and was dismissed from military service in July 1902.

Discharged from the military under medical terms, Haarmann was awarded a full military pension (which he would continue to receive until his 1924 arrest for murder).[3] Upon his military discharge, Haarmann returned to live with his fiancée in Hanover, briefly working in the small business his father had established, before unsuccessfully filing a maintenance lawsuit against his father, citing that he was unable to work due to the ailments noted by the military. His father successfully contested Haarmann's suit, and the charges would be dropped. The following year, a violent fight between father and son resulted in Haarmann's father himself unsuccessfully initiating legal proceedings against his son, citing verbal death threats and blackmail as justification to have his son returned to a mental institution. These charges would themselves be dropped due to a lack of corroborating evidence. Nonetheless, Haarmann was ordered to undertake a psychiatric examination in May 1903. This examination was conducted by a Dr. Andrae, who concluded that, although morally inferior, Haarmann was not mentally unstable.

With financial assistance from his father, Haarmann and his fiancée opened a fishmongery. Haarmann himself briefly attempted to work as an insurance salesman, before being officially classified as disabled and unable to work[8] by the military in 1904. As a result, his monthly military pension was increased. The same year, his fiancée—pregnant with his child—terminated their engagement. According to Haarmann, this ultimatum had occurred when he had accused his fiancée of conducting an affair. As the fishmongery had been registered in her name,[8] Erna Haarmann simply ordered her husband to leave the premises.

Criminal career

For the next decade, Haarmann primarily lived as a petty thief, burglar and con artist. Although he did occasionally obtain legitimate employment, he invariably stole from his employers or their customers. Beginning in 1905, he served several short prison sentences for offenses such as larceny, embezzlement and assault. On one occasion when working legitimately as an invoice clerk, Haarmann became acquainted with a female employee with whom he would later claim to have robbed several tombstones and graves between 1905 and 1913 (he was never charged with these offenses).[9] Nonetheless, Haarmann spent the majority of the years between 1905 and 1912 in jail.

In late 1913, Haarmann was arrested for burglary. A search of his home revealed a hoard of stolen property linking him to several other burglaries. Despite protesting his innocence, Haarmann was charged with and convicted of a series of burglaries and frauds. He was sentenced to five years' imprisonment for these offenses.

Due to compulsory conscription resulting from World War I, Germany saw a shortage of available domestic manpower. In the final years of his prison sentence, Haarmann was permitted to work throughout the day in the grounds of various manor houses near the town of Rendsburg,[10] with instructions to return to prison each evening. Upon his release from prison in April 1918, Haarmann initially moved to Berlin, before opting to return to Hanover, where he briefly lived with his sister before renting a single room apartment in August 1918.

According to Haarmann, he was struck by the poverty of the German nation as a result of the loss the nation had suffered in World War I. Through his initial efforts to both trade and purchase stolen property at Hanover Central Station, Haarmann established several criminal contacts with whom he could trade in contraband property, and he immediately reverted to the criminal life he had lived before his 1913 arrest.

Police informant

As a result of the poverty the nation was enduring in the years immediately following World War I, many basic commodities became increasingly scarce and expensive to purchase, fueling an increase in crimes such as theft, assault and murder in addition to a significant increase in black market trading. Due to the peace treaty signed in 1919, Germany had no army, was forbidden to participate in the arms trade, and its police forces—badly paid and overstretched—had limited resources at their disposal. In this environment, police were welcoming of assistance and information from the public.[11]

Despite police knowledge that Haarmann was both a known criminal and a known homosexual[12] (then illegal and punishable by imprisonment in Germany), Haarmann gradually began to establish a relationship with Hanover police as an informer, largely as a means of redirecting the attention of the police from himself in his own criminal activities, and to facilitate his access to young males. By 1919, he is known to have regularly patrolled Hanover station,[13] and to have provided police with information relating to Hanover's extensive criminal network. With the cooperation of several police officials, Haarmann devised a ruse whereby he would offer to fence or store stolen property at his premises, then pass this information to police, who would then raid his property at agreed times and arrest these contacts.[14] To remove any suspicion as to his treachery reaching the criminal fraternity, Haarmann himself would be arrested in these raids. Moreover, on numerous occasions, he is known to have performed citizen's arrests upon commuters for offenses such as travelling on forged documents. As a result of these activities, police began to rely on Haarmann as a reliable source of information regarding various criminal activities in the city, and he was allowed to patrol Hanover station largely at will.

Murders

Between 1918 and 1924, Haarmann is known to have committed at least 24 murders, although he is suspected of murdering a minimum of 27. All of Haarmann's victims were males between the ages of 10 and 22, the majority of whom were in their mid- to late-teens. The victims would be lured back to one of three addresses in which Haarmann is known to have resided throughout the years he is known to have killed upon the promise of assistance, accommodation, work, or under the pretense of arrest. At Haarmann's apartment, the victim would typically be given food and drink before Haarmann bit into his Adam's apple, often as he was strangled.[15] In many instances, this act would cause the victim to die of asphyxiation, although on several occasions, Haarmann would bite completely through his victims' Adams apple and trachea.[16] (Haarmann would refer to the act of biting through his victims' neck as being his "love bite".)[17]

All of Haarmann's victims were dismembered before their bodies were discarded, usually in the Leine River, although the dismembered body of his first known victim had simply been buried,[18] and the body of his last victim had been thrown into a lake located at the entrance to the Herrenhausen Gardens.

The personal possessions of Haarmann's victims would typically be retained for the personal use of Haarmann or his lover, Hans Grans, or be sold on the black market through criminal contacts both men had established at Hanover Central Station, although the personal possessions of some victims were sold to legitimate retailers. In several instances, both Haarmann and Grans are known to have given possessions belonging to various victims to acquaintances as gifts.[19]

Following Haarmann's arrest, rumors would circulate that the flesh of his victims had been consumed by Haarmann himself or sold upon the black market as pork or horse meat.[20] Although no physical evidence was ever produced to confirm these theories, Haarmann was known to be an active trader in contraband meat,[21] which was invariably boneless, diced and often sold as mince.[22] To the various individuals who questioned where he had acquired the meat, Haarmann would explain he had purchased the product from a butcher named "Karl," although investigators would later note that the stories Haarmann told his acquaintances regarding the origins of this individual varied.

First known victim

Haarmann's first known victim was a 17-year-old runaway named Friedel Rothe. When Rothe disappeared on 27 September 1918, his friends told police he was last seen with Haarmann, who at the time of this first known murder resided in a single room apartment at 27 Cellerstraße. Under pressure from Rothe's family, police raided Haarmann's apartment in October 1918, where they found their informer in the company of a semi-naked 13-year-old boy.[23] He was charged with both the sexual assault and battery[24] of a minor, and sentenced to nine months' imprisonment. (Haarmann would later state to detectives that at the time they had searched his apartment, the head of Friedel Rothe, wrapped in newspaper, had been stowed behind his stove.)[25]

Haarmann avoided serving his sentence throughout 1919. That October, he met an 18-year-old youth named Hans Grans, who had run away from his home in Berlin following an argument with his father on 1 October. Grans had slept rough in and around Hanover station for approximately two weeks before he encountered Haarmann as he (Grans) sold old clothes at Hanover station.[16]

Acquaintance with Hans Grans

In his subsequent confessions to police, Grans stated that, although his sexual orientation was heterosexual, he himself initiated contact with Haarmann, with the intention of selling his body, having heard through acquaintances he had established in Hanover of Haarmann's homosexuality.[26] Haarmann himself stated following his arrest that he viewed Grans as being "like a son" to him, adding that he "pulled him [Grans] out of the ditch and tried to make sure he didn't go to the dogs."[27]

Shortly after their initial acquaintance, Haarmann invited the youth to move into his apartment, and Grans would subsequently become Haarmann's lover and criminal accomplice.[28] According to Haarmann, although he was smitten with Grans,[27] he gradually became aware the youth manipulated and, occasionally, mocked him. On several occasions throughout the years Grans resided with Haarmann, the youth would be temporarily evicted following heated arguments in which he ridiculed or rebuffed Haarmann's threats or accusations against him, only for Haarmann to shortly thereafter plead with the youth to return to live with him. Despite the manipulation Haarmann endured at the hands of his accomplice, he later claimed to tolerate the capitulation as he craved Grans' companionship and affection,[29] adding: "I had to have someone I meant everything to."[30]

Haarmann served the nine-month prison sentence imposed in 1918 for sexual assault and battery between March and December 1920. Upon his release, he again regained the trust of the police and again became an informer. Haarmann initially resided in a hotel, before he and Grans lodged with a middle-class family.[31]

Through criminal contacts, Haarmann became aware of a vacant ground floor apartment located at 8 Neue Straße.[32] The apartment was located in a densely populated, old house located alongside the Leine River. Haarmann secured a letting agreement with the landlady, ostensibly to use the property for storage purposes. He and Grans moved into 8 Neue Straße on 1 July 1921.

Subsequent murders

Haarmann's subsequent victims largely consisted of young male commuters, runaways and, occasionally, male prostitutes, whom he would typically encounter in or around Hanover's central railway station. The second murder Haarmann is known to have committed occurred on 12 February 1923. The victim was a 17-year-old pianist named Fritz Franke, whom Haarmann had encountered at Hanover Central Station and invited to his Neue Straße residence, where he had introduced the youth to Hans Grans and two female acquaintances (one of whom was Grans' female lover).[33] According to Grans' lover, that evening, Grans had whispered in her ear: "Hey! He's going to be trampled on today."[34] The following day, both these acquaintances returned to Haarmann's apartment, where they were informed by Haarmann that Franke had travelled to Hamburg.

Speculation remains as to Grans' knowledge of Haarmann's intentions towards Franke when he made this comment to the two female acquaintances. According to Haarmann, following this murder, Grans had arrived unannounced at his apartment, where he had observed Franke's nude body lying upon Haarmann's bed. Grans had simply looked at him and asked, "When shall I come back again?"[35]

Five weeks after the murder of Franke, on 20 March, Haarmann encountered a 17-year-old named Wilhelm Schulze at Hanover station.[19] Schulze had been travelling to work when he encountered Haarmann. No human remains identified as belonging to Schulze were ever found, although most of his clothing had been in the possession of Haarmann's landlady, Elisabeth Engel, at the time of his arrest. Two more victims are known to have been murdered at 8 Neue Straße before Haarmann vacated the apartment in June: 16-year-old Roland Huch, who disappeared on 23 May after informing a close friend he intended to run away from home and join the Marines; and 19-year-old Hans Sonnenfeld, who disappeared on or about 31 May and whose distinctive yellow overcoat Haarmann is known to have worn after the youth's murder.

On 9 June 1923, Haarmann moved into a single-room attic apartment at 2 Rote Reihe. Two weeks after moving into this address, on 25 June, a 13-year-old boy named Ernst Ehrenberg—the son of Haarmann's neighbor—disappeared while running an errand for his father. His school cap and braces would be found in Haarmann's apartment following his arrest.[36] Two months later, on 24 August, an 18-year-old office clerk named Heinrich Struß was reported missing by his aunt (with whom he lived). Many of Struß's belongings would also be found in Haarmann's apartment. Struß's murder would be followed one month later by the murder of a 17-year-old named Paul Bronischewski, who disappeared en route to the city of Bochum, having worked with his uncle in Saxony-Anhalt throughout the summer. Subsequent police enquiries suggested Bronischewski had likely alighted the train at Hanover, whereupon he had encountered Fritz Haarmann. Bronischewski's jacket, knapsack, trousers and towel would all be found in the possession of Haarmann following his arrest.

Haarmann is next known to have killed on or about 30 September 1923. The victim was 17-year-old Richard Gräf, who last informed his family he had met an individual at Hanover station who "knows of a good job for me." Two weeks later, on 12 October, a 16-year-old Gehrden youth named Wilhelm Erdner failed to return home from work. Subsequent enquiries by Erdner's parents revealed the youth had become acquainted with a Detective Fritz Honnerbrock (a pseudonym used by Haarmann) shortly before his disappearance. Both Haarmann and Grans subsequently sold Erdner's bicycle on 20 October. Within a week of having sold this bicycle, Haarmann had killed two further victims: 15-year-old Hermann Wolf, who disappeared from Hanover station on 24 October, and 13-year-old Heinz Brinkmann, who was seen by a witness standing in the entrance to Hanover station at 11 p.m. on 27 October, having missed his train home to the town of Clausthal. (Haarmann would deny having killed Hermann Wolf at his trial, and was acquitted of this murder.)

On 10 November 1923, a 17-year-old apprentice carpenter from the city of Düsseldorf named Adolf Hannappel disappeared from Hanover station. He was seen by several witnesses sitting upon a trunk in the waiting room. These witnesses also positively identified Hans Grans—in the company of Haarmann—pointing towards the youth, who shortly thereafter was observed walking towards a cafe in the company of these two men. One month later, on 6 December, 19-year-old Adolf Hennies disappeared. He had been seeking employment at the time of his disappearance. None of the human remains recovered were identified as belonging to Hennies, whom Haarmann specifically admitted to dismembering, but denied killing. In subsequent court testimony vehemently disputed by Grans, Haarmann claimed he had returned home to find Hennies's body—missing his signature "love bite"—lying naked on his bed, with Grans and another criminal acquaintance named Hugo Wittkowski stating the youth was, "One of yours." (Neither Haarmann nor Grans were convicted of Hennies's murder due to conflicting testimony.)

1924

The first victim killed by Haarmann in 1924 was 17-year-old Ernst Spiecker, who disappeared on 5 January. Although subsequent trial testimony from a friend of Spiecker would indicate Haarmann had become acquainted with this youth before his murder, Haarmann stated he would simply have to "assume" this youth was one of his victims due to all his personal possessions being found in his or Grans' possession following his arrest.[37] Ten days later, Haarmann killed a 20-year-old named Heinrich Koch, whom he is also believed to have been acquainted with prior to the youth's murder. The following month, Haarmann is known to have killed two further victims: 19-year-old Willi Senger, who disappeared from the suburb of Linden-Limmer on 2 February, having informed his sister he was to travel with a friend; and 16-year-old Hermann Speichert, who was last seen by his sister on 8 February.

Haarmann is not known to have killed again until on or about 1 April, when he is believed to have killed an acquaintance named Hermann Bock. Although cleared of this murder at his trial, Haarmann was in possession of Bock's clothing when arrested, and he is known to have given the youth's suitcase to his landlady; moreover, Haarmann is known to have actively dissuaded several of Bock's acquaintances from reporting the youth missing. One week later, on 8 April, 16-year-old Alfred Hogrefe disappeared from Hanover station, having run away from home in the town of Lehrte on 2 April. Hogrefe's murder would be followed 9 days later by that of a 16-year-old apprentice named Wilhelm Apel, whom Haarmann encountered on his "patrols" of the Hanover-Leinhausen station.

On 26 April, 18-year-old Robert Witzel disappeared after borrowing 50 Pfennigs from his mother, explaining he intended to visit a travelling circus.[38] Enquiries by the youth's parents revealed their son had accompanied an "official from the railway station" to the circus. Haarmann himself would later state he had killed Witzel the same evening and, having dismembered the youth's body, had thrown the remains into the Leine River.

Two weeks after the murder of Witzel, Haarmann killed a 14-year-old named Heinz Martin, who was last seen by his mother on 9 May and who is believed to have been abducted at Hanover station. All his clothing was later found in Haarmann's apartment. Less than three weeks later, on 26 May, a 17-year-old travelling salesman from the town of Kassel named Fritz Wittig, whom Haarmann would later state he had killed upon the insistence of Grans as he had worn a "good new suit" Grans coveted,[39] was dismembered and discarded in the Leine River. The same day Wittig is believed to have been killed, Haarmann killed his youngest known victim, 10-year-old Friedrich Abeling, who disappeared while truanting from school. His murder would be followed less than two weeks later by that of 16-year-old Friedrich Koch, who was approached by Haarmann on 5 June as he walked to college. Two acquaintances of Koch would later testify at Haarmann's trial that, as they walked with Koch to college, Haarmann had approached Koch and tapped the youth on the boot with his walking stick and stated: "Well, boy, don't you recognize me?"[40]

Haarmann killed his final victim, 17-year-old Erich de Vries, on 14 June. De Vries had encountered Haarmann at Hanover station. His dismembered body would later be found in a lake located near the entrance to the Herrenhausen Gardens. Haarmann would confess that it had taken him four separate trips to carry de Vries's dismembered remains—carried in the bag which had belonged to Friedrich Koch—to the location he had disposed of them.[41]

Discoveries

On 17 May 1924,[42] two children playing near the Leine River discovered a human skull. Determined to be that of a young male aged between 18 and 20 and bearing evidence of knife wounds, police were skeptical as to whether a murder had been committed or whether the skull had either been discarded in this location by grave robbers, or placed there in a tasteless prank by medical students. Furthermore, police theorized the skull may have been discarded in the river at Alfeld, which had recently experienced an outbreak of typhoid.[42] Two weeks later, on 29 May, a second skull was found behind a mill race located close to the scene of the earlier discovery. This skull was also identified as having been that of a young male aged between 18 and 20. Shortly thereafter, two boys playing in a field close to the village of Döhren discovered a sack containing numerous human bones.

Two more skulls would be found on 13 June: one upon the banks of the Leine River; another located close to a mill in west Hanover. Each of the skulls had been removed from the vertebrae with a sharp instrument. One skull had belonged to a male in his late-teens, whereas the other had belonged to a boy estimated to have been aged between 11 and 13 years old. In addition, one of these skulls also bore evidence of having been scalped.

For more than a year prior to these discoveries, rumors had circulated amongst the population of Hanover regarding the fate of the sheer number of children and teenagers who had been reported missing in the city; the discoveries sparked fresh rumors regarding missing and murdered children. In addition, various newspapers responded to these discoveries and the resulting rumors by harking to the disproportionate number of young people who had been reported missing in Hanover between 1918 and 1924. (In 1923 alone, almost 600 teenage boys and young men had been reported missing in Hanover.)[2]

On 8 June, several hundred Hanover residents converged close to the Leine River and searched both the banks of the river and the surrounding areas, discovering a number of human bones, which were handed to the police. In response to these latest discoveries, police decided to drag the entire section of the river which ran through the center of the city. In doing so, they discovered more than 500 further human bones and sections of bodies—many bearing knife striations—which were later confirmed by a court doctor as having belonged to at least 22 separate human individuals. Approximately half of the remains had been in the river for some time, whereas other bones and body parts had been discarded in the river more recently. Many of the recent and aged discoveries bore evidence of having been dissected—particularly at the joints. Over 30 percent of the remains were judged to have belonged to young males aged between 15 and 20.

Suspicion for the discoveries quickly fell upon Fritz Haarmann, who was known to both the police and the criminal investigation department as a homosexual who had amassed 15 previous convictions dating from 1896 for various offenses including child molestation and the sexual assault and battery of a minor.[24] Moreover, Haarmann had been connected to the 1918 disappearances of Friedel Rothe and a 14-year-old named Hermann Koch (who had disappeared weeks prior to Rothe). Haarmann was placed under surveillance. Being a trusted police informant, Haarmann was known to frequent Hanover Central Station. As he was well-known to many officers from Hanover, two young policemen were drafted from Berlin to pose as undercover officers and discreetly observe his movements. The surveillance of Haarmann began on 18 June 1924.

Arrest

On the night of 22 June, Haarmann was observed by the two undercover officers prowling Hanover's central station. He was soon observed arguing with a 15-year-old boy named Karl Fromm, then to approach police and insist they arrest the youth on the charge of travelling upon forged documents. Upon his arrest, Fromm informed police he had been living with Haarmann for four days, and that he had been repeatedly raped by his accuser, sometimes as a knife had been held to his throat. Haarmann was arrested the following morning and charged with sexual assault.

Following his arrest. Haarmann's attic apartment at No. 2 Rote Reihe was searched. Haarmann had lived in this single room apartment since June 1923. The flooring, walls and bedding within the apartment were found to be extensively bloodstained.[43] Haarmann initially attempted to explain this fact as a by-product of his illegal trading in contraband meat. Various acquaintances and former neighbors of Haarmann were also extensively questioned as to his activities. Many fellow tenants and neighbors of the various addresses in which Haarmann lived since 1920 commented to detectives about the number of teenage boys they had observed visiting his various addresses. Moreover, some had seen him leaving his property with concealed sacks, bags or baskets—invariably in the late evening or early morning hours.[44] Two former tenants informed police that, in the spring of 1924, they had discreetly followed Haarmann from his apartment and observed him discarding a sack into the Leine River.

The clothes and personal possessions found at Haarmann's apartment and in the possession of his acquaintances were suspected as being the property of missing youths: all were confiscated and put on display at Hanover Police Station, with the parents of missing teenage boys from across Germany invited to look at the items. As successive days passed, an increasing number of items of clothing and personal possessions belonging to missing youths were identified by family members as having belonged to their sons and brothers. Haarmann did initially attempt to dismiss these successive revelations as being circumstantial in nature by explaining he had acquired many of these items through his business of trading in used clothing, with other items being left at his apartment by youths with whom he had engaged in sexual activity.

The turning point came when, on 29 June, clothes, boots and keys found stowed at Haarmann's apartment were identified as belonging to a missing 18-year-old named Robert Witzel. A skull which had been found in a garden on 20 May[38] (which had not initially been connected with later skeletal discoveries) had been identified as that of the missing youth. A friend of Witzel identified a police officer seen in the company of the youth the day prior to his disappearance as Fritz Haarmann. Confronted with this evidence, Haarmann briefly attempted to bluster his way out of these latest and most damning pieces of evidence. When Robert Witzel's jacket was found in the possession of his landlady and he was confronted with various witnesses' testimony as to his destroying identification marks upon the clothing, Haarmann broke down and had to be supported by his sister.

Confession

Faced with this latest evidence, and upon the urging of his sister,[45] Haarmann confessed to raping, killing and dismembering many young men in what he initially described as a "rabid sexual passion"[45] between 1918 and 1924. According to Haarmann, he had never actually intended to murder any of his victims, but would be seized by an irresistible urge to bite into or through their Adam's apple—often as he manually strangled them—in the throes of ecstasy, before typically collapsing atop the victim's body. Only one victim had escaped from Haarmann's apartment after he had attempted to bite into his Adam's apple, although this individual is not known to have reported the attack to police.[46]

All of his victims' bodies had been disposed of via dismemberment shortly after their murder, and Haarmann was insistent that he had found the act of dismemberment extremely unpleasant; he had, he stated, been ill for eight days after his first murder.[47] Nonetheless, Haarmann was insistent that his passion at the moment of murder was invariably "stronger than the horror of the cutting and the chopping" which would inevitably follow, and would typically take up to two days to complete.[48]

To fortify himself to dismember his victims' bodies, Haarmann would pour himself a cup of strong black coffee, then place the body of his victim upon the floor of this apartment and cover the face with cloth, before first removing the intestines, which he would place inside a bucket. A towel would then be repeatedly placed inside the abdominal cavity to soak the collecting blood. He would then make three cuts between the victim's ribs and shoulders, then "take hold of the ribs and push until the bones around the shoulders broke."[15] The victim's heart, lungs and kidneys would then be removed, diced, and placed in the same bucket which held the intestines before the legs and arms would be severed from the body. Haarmann would then begin paring the flesh from the limbs and torso. This surplus flesh would be disposed of in the toilet or, usually, in the nearby river.

The final section of the victims' bodies to be dismembered was invariably the head. After severing the head from the torso, Haarmann would use a small kitchen knife to strip all flesh from the skull, which he would then wrap in rags and place face downwards upon a pile of straw and bludgeon with an axe until the skull splintered, enabling him to access the brain. This he would also place in a bucket, which he would pour, alongside the "chopped up bones" in the Leine River.[21]

Haarmann was insistent that none of the skulls found in the Leine River had belonged to his victims, and that the forensic identification of the skull of Robert Witzel was mistaken, as he had almost invariably smashed his victims' skulls to pieces. The exceptions being those of his earliest victims—killed several years prior to his arrest—and that of his last victim, Erich de Vries.[18] Although insistent that none of his murders had been premeditated, investigators discovered much circumstantial evidence suggesting that several murders had been planned hours or days in advance, and that Haarmann had both concocted explanations for his victims' disappearances and dissuaded acquaintances of his victims from filing missing persons' reports with Hanover police.[49] Investigators also noted that Haarmann would only confess to murders for which there existed evidence against him; on one occasion, Haarmann had stated: "There are some [victims] you don't know about, but it's not those you think."

When asked how many victims he had killed, Haarmann claimed, "Somewhere between 50 and 70." The police, however, could only connect Haarmann with the disappearance of 27 youths, and he was charged with 27 murders—some of which he claimed had been committed upon the insistence of Hans Grans, who was charged with being an accessory to murder on 15 July.[50] (In his initial confession to police, Haarmann stated that although Grans knew of many of his murders, and had personally urged him to kill two of the victims in order that he could obtain their clothing and personal possessions, Grans was otherwise not involved in the murder of the victims.)

On 16 August 1924, Haarmann underwent a psychological examination at a Göttingen medical school; on 25 September, he was judged competent to stand trial and returned to Hanover to await trial.

Trial

The trial of Fritz Haarmann and Hans Grans began on 4 December 1924. Haarmann was charged with the murder of 27 boys and young men who had disappeared between September 1918 and June that year. In 14 of these cases, Haarmann acknowledged his guilt,[48] although he claimed to be uncertain of the identification of the remaining 13 victims upon the list of charges. Grans pleaded not guilty to charges of being an accessory to murder in several of the murders.[51] The trial was conducted behind closed doors,[29] and all permitted to enter the courtroom were thoroughly searched.

The trial was one of the first major modern media events in Germany, and received extensive international press coverage as the "most revolting [case] in German criminal history."[39] Varying sensational headlines—in which Haarmann was variously referred to by such titles as the "Butcher of Hanover," the "The Vampire of Hanover," and the "Wolf Man"—continuously appeared in the press.

Due to the carnal and graphic nature of the murders, no members of the public were permitted inside the courtroom in the opening days of the trial, as each murder was discussed in detail.[52] Although adamant the ultimate reason he killed was a "mystery" to him,[29] and that he was unable to remember the names or faces of most of his victims, Haarmann—who insisted upon conducting his own defense—readily confessed to having killed many of the victims for whose murder he was tried and to retaining and selling many of their possessions, although he denied having sold any body parts as meat. Haarmann's denial that he had consumed or sold human flesh would be supported by a medical expert, who testified on 6 December that none of the meat found in Haarmann's apartment following his arrest was human.[39]

When asked to identify photographs of his victims, Haarmann became taciturn and dismissive as he typically claimed to be unable to recognize any of his victims' photographs; however, in instances where he claimed to be unable to recognize his victims' faces but the victims' clothing had been found in his possession, he would simply shrug and make comments to the effect of, "I probably killed him."[52] For example, when asked to identify a photograph of victim Alfred Hogrefe, Haarmann stated: "I certainly assume I killed Hogrefe, but I don't remember his face."[53]

Numerous exhibits were introduced into evidence in the opening days of the trial, including 285 bones and skulls determined as belonging to young men under 20 years of age[54] which had been retrieved from the Leine River, the bucket into which he had stored and transported human remains, and the extensively bloodstained camp bed upon which he had killed many of the victims at his Rote Reihe address.[39] As had been the case when earlier asked whether he could recognize the photographs of any of his victims, Haarmann's demeanour became dismissive upon the introduction of these exhibits; he denied any of the skulls introduced into evidence had belonged to his victims, stating he had "mashed" the skulls of his victims, and had thrown only one undamaged skull into the river.[55]

Several acquaintances and criminal associates of Haarmann testified for the prosecution, including former neighbors who testified to having purchased brawn or mince from Haarmann, whom they noted regularly left his apartment with packages of meat, but rarely arrived with them. Haarmann's landlady, Elisabeth Engel, testified that Haarmann would regularly pour chopped pieces of meat into boiling water and would strain fat from meat he (Haarmann) claimed was pork. This fat would invariably be poured into bottles. On one occasion in April 1924,[20] Haarmann's landlady and her family became ill after eating sausages in skins Haarmann had claimed were sheep's intestines. Another neighbor testified to the alarming number of youths whom he had seen entering Haarmann's Neue Straße apartment, but whom he seldom observed leaving the address. This neighbor had assumed Haarmann was selling youths to the Foreign Legion;[22] another neighbor testified to having observed Haarmann throw a sack of bones into the Leine River. Two female acquaintances of Hans Grans also testified how, on one occasion in 1923, they had discovered what they believed to be a human mouth boiling in a soup kettle in Haarmann's apartment;[56] these witnesses testified they had taken the item to Hanover police, who had simply replied the piece of flesh may be a pig's snout. (The origins of the contraband meat in which Haarmann had traded were never established.)

By the second week of the trial,[57] testimony had begun to focus upon the extent of police knowledge of the criminal activities Haarmann had engaged upon following his 1918 release from prison and issues relating to the trust bestowed upon him.[57] Until Haarmann had been arrested for sexual assault upon Karl Fromm and his apartment had been searched, the police had seemingly never seriously suspected that the individual responsible for the sharp increase in missing person cases relating to boys and young men filed in Hanover in 1923 and 1924, or the discovery of more than 500 human bones in and around the Leine River in May and June 1924, was actually an individual whom they had regarded as a trusted informant, despite the fact some of the victims were last seen in his company, and that he had amassed a lengthy criminal record for various criminal offenses including sexual assault and battery.[58]

The trial lasted barely two weeks, and saw a total of 190 witness called to testify.[48] These witnesses included the parents of the victims, who were asked to identify their sons' possessions. Also called to testify were police officers, psychiatrists and numerous acquaintances of both Haarmann and Grans. On 19 December 1924,[59] court reconvened to impose sentence upon both defendants. Judged sane and accountable for his actions, Haarmann was found guilty of 24 of the 27 murders and sentenced to death by beheading.[60] He was acquitted of three murders which he had denied committing. Upon hearing the sentence, Haarmann stood before the court and proclaimed, "I accept the verdict fully and freely."[61] Grans became hysterical upon hearing he had been found guilty of incitement to murder and sentenced to death by beheading in relation to the murder of victim Adolf Hannappel,[62] with an additional sentence of 12 years' imprisonment for being an accessory to murder in the case of victim Fritz Wittig.[63] Upon returning to his cell after hearing the verdict, Grans collapsed.[64]

In the case of Hannappel, several witnesses had testified to having seen Grans, in the company of Haarmann, pointing towards the youth. Haarmann claimed this was one of two murders committed upon the insistence of Grans and for this reason, Grans was sentenced to death. In the case of Wittig, police had found a handwritten note from Haarmann, dated the day of Wittig's disappearance and signed by both he and Grans, in which Grans had agreed to pay Haarmann 20 Goldmarks for the youth's suit. As the note indicated Grans' possible knowledge in the disappearance of Wittig, he was convicted of being an accomplice to Haarmann in this murder and sentenced to 12 years' imprisonment.

Haarmann made no appeal against the verdict;[63] claiming his death would atone for his crimes[65] and stating that, were he at liberty, he would likely kill again. Grans did lodge an appeal against his sentence, although his appeal was rejected on 6 February 1925.[66]

| "Condemn me to death. I ask only for justice. I am not mad. Make it short; make it soon. Deliver me from this life, which is a torment. I will not petition for mercy, nor will I appeal. I want to pass just one more merry night in my cell, with coffee, cheese and cigars, after which I will curse my father and go to my execution as if it were a wedding."[67] |

| Fritz Haarmann addressing the court prior to his sentencing. December 1924. |

Execution

At 6 a.m. on the morning of 15 April 1925, Fritz Haarmann was beheaded by guillotine in the grounds of Hanover prison.[68] In accordance with German tradition, Haarmann was not informed of his execution date until the prior evening. Upon receipt of the news, he observed prayer with his pastor, before being granted his final wishes of an expensive cigar to smoke and Brazilian coffee to drink in his cell.[69]

No members of the press were permitted to witness the execution, and the event was seen by only a handful of witnesses.[69] According to published reports, although Haarmann was pale and nervous, he maintained a sense of bravado as he walked to the guillotine. The last words Haarmann spoke were: "I am guilty, gentlemen, but, hard though it may be, I want to die as a man."[70] Immediately prior to placing his head upon the execution apparatus, Haarmann added: "I repent, but I do not fear death."[71]

Aftermath

- Following Haarmann's execution, sections of his brain were removed for forensic analysis. An examination of slices of Haarmann's brain revealed traces of meningitis,[72] although no sections of Haarmann's brain were permanently preserved. Nonetheless, Haarmann's head was preserved in formaldehyde and remained in the possession of the Göttingen medical school from 1925 until 2014, when it was cremated.[73]

- The remains of Haarmann's victims were buried together in a communal grave in Stöckener Cemetery in February 1925. In April 1928, a large granite memorial in the form of a triptych, inscribed with the names and ages of the victims, was erected over the communal grave.[74]

- The discovery of a letter from Haarmann declaring Grans' innocence subsequently led to Grans receiving a second trial. This letter was dated 5 February 1925, and was addressed to the father of Hans Grans.[75] In this letter, Haarmann claimed that although he had been frustrated at having been seen as little more than a "meal ticket" by Grans, he (Grans) "had absolutely no idea that I killed". Furthermore, Haarmann claimed many of his accusations against Grans prior to his trial had been obtained under extreme duress, and that he had falsely accused Grans of instigating the murders of Hannappel and Witzel as a means of revenge. Haarmann claimed that his pastor would be informed as to the contents and the authenticity of the letter.

- Hans Grans was retried in January 1926. He was charged with aiding and abetting Haarmann in the murders of victims Adolf Hannappel and Fritz Wittig. Although Grans had stated in one address to the judge at his second trial that he expected to be acquitted,[76] on 19 January, he was found guilty of aiding and abetting Haarmann in both cases and sentenced to two concurrent 12-year sentences.

- After serving his 12-year sentence, Hans Grans continued to live in Hanover until his death in 1975.

- The case stirred much discussion in Germany regarding methods used in police investigation, the treatment of mentally ill offenders, and the validity of the death penalty.[77] However, the most heated topic of discussion in relation to the murders committed by Haarmann were issues relating to the subject of homosexuality, which was then illegal and punishable by imprisonment in Germany. The discovery of the murders subsequently stirred a wave of homophobia throughout Germany, with one historian noting: "It split the [gay rights] movement irreparably, fed every prejudice against homosexuality, and provided new fodder for conservative adversaries of legal sex reform."[78]

Victims

1918

- 27 September: Friedel Rothe, 17. Encountered Haarmann in a cafe, having run away from home. Haarmann claimed to have buried Rothe in Stöckener cemetery.

1923

- 12 February: Fritz Franke, 17. Franke was a pianist, originally from Berlin. He encountered Haarmann in the Hanover station waiting rooms. All Franke's personal possessions were given to Grans.

- 20 March: Wilhelm Schulze, 17. An apprentice writer who last informed his best friend he intended to run away from home. Schulze's clothing was found in the possession of Haarmann's landlady.

- 23 May: Roland Huch, 16. Huch vanished from Hanover station after running away from home. His clothing was traced to a lifeguard who testified at Haarmann's trial he had obtained them via Haarmann.

- c. 31 May: Hans Sonnenfeld, 19. A runaway from the suburb of Limmer who is known to have associated with acquaintances at Hanover station. Sonnenfeld's coat and tie were found at Haarmann's apartment.[79]

- 25 June: Ernst Ehrenberg, 13. The first known victim killed at Haarmann's Rote Reihe address. Ehrenberg was the son of Haarmann's own neighbor. He never returned home after running an errand for his parents.

- 24 August: Heinrich Struß, 18. A carpenter's son from the suburb of Egestorf. Struß was last seen at a Hanover cinema. Haarmann was in possession of the youth's violin case when arrested.

- 24 September: Paul Bronischewski, 17. Vanished as he travelled home to the city of Bochum after visiting his uncle in Groß Garz. He was offered work by Haarmann when he alighted the train at Hanover.

- c. 30 September: Richard Gräf, 17. Disappeared after telling his family a detective from Hanover had found him a job. Haarmann's landlady is known to have pawned Gräf's overcoat.[80]

- 12 October: Wilhelm Erdner, 16. A locksmith's son from the town of Gehrden. Erdner disappeared as he cycled to work. Haarmann is known to have sold Erdner's bicycle on 20 October.

- 24 October: Hermann Wolf, 15. Wolf was last seen by his brother in the vicinity of Hanover station; his belt buckle was later found in Haarmann's apartment,[81] although Haarmann would deny having killed Wolf at his trial. Haarmann was acquitted of this murder.

- 27 October: Heinz Brinkmann, 13. Vanished from Hanover station after missing his train home to Clausthal. A witness would later testify to having seen Haarmann and Grans conversing with Brinkmann in the waiting rooms at Hanover station.[82]

- 10 November: Adolf Hannappel, 17. One of the few murder victims whom Haarmann readily confessed to killing.[83] Hannappel was seen by several witnesses sitting in the waiting rooms at Hanover station; all of whom would later testify to having seen Haarmann approach Hannappel. Haarmann would himself claim to have committed this murder upon the urging of Hans Grans.

- 6 December: Adolf Hennies, 19. Hennies disappeared while looking for work in Hanover; his coat was found in the possession of Hans Grans. Haarmann would claim at his trial that, although he had dismembered Hennies's body, Grans and another acquaintance had been responsible for this murder.[17] Haarmann was acquitted of this murder.

1924

- 5 January: Ernst Spiecker, 17. Last seen by his mother on his way to appear as a witness at a trial. Grans was wearing Spiecker's shirt at the time of his arrest.

- 15 January: Heinrich Koch, 20. Although Haarmann claimed to be unable to recognize a photo of Koch, the youth was known to be an acquaintance of his. Koch's clothing and personal possessions had been given to the son of Haarmann's landlady.

- 2 February: Willi Senger, 19. Senger had known Haarmann prior to his murder. Although Haarmann initially denied any involvement in the youth's disappearance, police established Haarmann had regularly worn Senger's coat after the youth had vanished.

- 8 February: Hermann Speichert, 16. An apprentice electrician from Linden-Limmer. Speichert's clothing is known to have been sold by the son of Haarmann's landlady; his geometry kit was given to Grans as a gift.

- c. 1 April: Hermann Bock, 22. Bock was a labourer from the town of Uelzen, who had known Haarmann since 1921. He was last seen by his friends walking towards Haarmann's apartment. Although Haarmann was wearing Bock's suit when arrested, he was acquitted of this murder.

- 8 April: Alfred Hogrefe, 16. Ran away from home on 2 April following a family argument. He was repeatedly seen in the company of Haarmann at Hanover station in the days prior to his murder. All of Hogrefe's clothes were traced to Haarmann, Grans, or Haarman's landlady.[84]

- 17 April: Wilhelm Apel, 16. Disappeared on his way to work; Apel was lured from the Hanover-Leinhausen station to Haarmann's apartment. Much of his clothing had been sold by Haarmann's landlady.

- 26 April: Robert Witzel, 18. Last seen visiting a travelling circus; Witzel's skull was found May 20. The remainder of his body had been thrown into the Leine River.

- 9 May: Heinrich Martin, 14. An apprentice locksmith from the city of Chemnitz. His leather marine cap, shirt and cardigan were all found in Haarmann's apartment. It is speculated that Martin disappeared from Hanover station while looking for work.[85]

- 26 May: Fritz Wittig, 17. A 17-year-old travelling salesman from the town of Kassel. According to Haarmann, he had not wanted to kill Wittig, but had been persuaded to "take the boy" by Grans, who coveted Wittig's suit.

- 26 May: Friedrich Abeling, 10. The youngest victim. Abeling disappeared while playing truant from school. His skull was found in the Leine River on 13 June.

- 5 June: Friedrich Koch, 16. Vanished on his way to college. Koch was last seen by two acquaintances in the company of Haarmann.[86]

- 14 June: Erich de Vries, 17. De Vries disappeared after informing his parents he intended to go for a swim in the Ohe River. Following his arrest, Haarmann led police to his dismembered skeletal remains, which he had discarded in a lake located at the entrance to the Herrenhausen Gardens.[18]

Footnotes

Haarmann was acquitted of three murders at his trial: those of Adolf Hennies, Hermann Wolf, and Hermann Bock. In each instance, strong circumstantial evidence existed attesting to his guilt.

In the case of Hermann Wolf, police established that prior to the youth's disappearance, he had informed his father he had conversed with a detective at Hanover station. Haarmann is known to have given many of Wolf's clothes to his landlady in the days immediately following his 44th birthday (shortly after Wolf was reported missing).[81] Moreover, the youth's distinctive belt buckle was found at Haarmann's Rote Reihe address. Haarmann only chose to deny this murder midway through his trial, following heated threats made against him by the father of the murdered youth.

Haarmann was acquitted of the murder of Adolf Hennies due to conflicting testimony regarding the circumstances as to whether he or Grans had actually murdered the youth. Although Haarmann admitted at his trial to having dismembering the Hennies's body, he claimed to have returned to his apartment and "found a dead body lying there," to which, he claimed, Grans had simply replied, "One of yours." Grans would deny this claim, and would state that he had bought Hennies's distinctive coat from Haarmann, who had warned him the coat was stolen. Due to this conflicting testimony, and the lack of an actual witness to the murder, neither Haarmann nor Grans were convicted of Hennies's murder.

In the case of Hermann Bock, several friends of Bock testified at Haarmann's trial that, prior to his arrest, they had been dissuaded from filing a missing person report upon the youth with police; these witnesses testified that Haarmann was insistent on filing the report himself (he had never done so). Other witnesses testified to having acquired various personal possessions belonging to the youth from Haarmann. In addition, a tailor testified at Haarmann's trial to having been asked by Haarmann to alter the suit. Haarmann repeatedly contradicted himself regarding his claims as to how he had acquired the youth's possessions. It is likely that Haarmann chose to deny this murder due to evidence suggesting the murder had been premeditated, as opposed to being committed in the throes of passion. He had known the youth for several years prior to his murder, and Bock was known to be heterosexual. Due to his denial of having committed this particular murder, Haarmann was acquitted.

Suspected victims

In September 1918,[24] Haarmann is believed to have killed a 14-year-old named Hermann Koch; a youth who disappeared just weeks prior to Friedel Rothe, his first confirmed victim. Haarmann is known to have kept company with Koch; he is also known to have written a letter to Koch's school providing an explanation for the youth's prolonged absence.[87] As had been the case in the disappearance of Friedel Rothe, police had searched Haarmann's Cellerstraße apartment in search of the youth, although no trace of Koch was found and charges against Haarmann in relation to the disappearance were dropped. Koch's father had petitioned in 1921 for Haarmann to be tried for his son's murder; however, his requests were officially rejected.[87]

Haarmann is also strongly suspected of the murder of Hans Keimes, a 17-year-old Hanover youth who was reported missing on 17 March 1922[87] and whose nude, bound body was found in a canal on 6 May. The cause of death was listed as strangulation, and the body bore no signs of mutilation. A distinctive handkerchief bearing Grans' name was found lodged in Keimes's throat.

Prior to the discovery of Keimes's body, Haarmann is known to have both visited the youth's parents offering to locate their son and to have immediately thereafter informed police that he believed Grans was responsible for Keimes's disappearance. (Hans Grans is known to have been in custody at the time of the disappearance of Keimes.)

Two weeks prior to the disappearance of Keimes, Haarmann had returned to his Neue Straße apartment, having served six months in a labour camp for several acts of theft he had committed in August 1921. Upon his return, Haarmann discovered that Grans had stolen much of his personal property and fraudulently obtained and spent his military pension while he had been incarcerated. This resulted in a violent argument between the two men, culminating in Haarmann evicting Grans. Shortly thereafter, Grans and a criminal acquaintance named Hugo Wittkowski had returned to and further ransacked the apartment. It is likely Haarmann committed this murder in an attempt to frame Grans in reprisal for the theft of his property and pension.

Haarmann was not tried for the murder of either Koch or Keimes. Officially, both cases remain unsolved.

The true tally of Haarmann's victims will never be known. Following his arrest, Haarmann made several imprecise statements regarding both the actual number of his victims he had killed, and when he had begun killing. Initially, Haarmann claimed to have killed "maybe 30, maybe 40"[88] victims. Later, he would claim the true number of victims he had killed was between 50 and 70. Investigators noted that he would only confess to murders for which sufficient evidence existed of his guilt. Of the 400 items of clothing found in Haarmann's apartment, only 100 were ever identified as having belonged to any of his known victims.

Media

Film

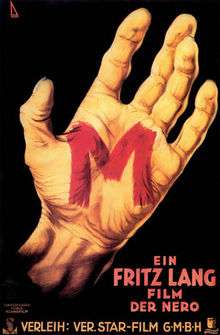

- The first film to draw inspiration from the Haarmann case, M, was released in 1931. Directed by Fritz Lang, M starred Peter Lorre as a fictional child killer named Hans Becker. In addition to drawing inspiration from the case of Fritz Haarmann, M was also inspired by the then-recent and notorious crimes of Peter Kürten and Carl Großmann.

- The film The Tenderness of the Wolves (Die Zärtlichkeit der Wölfe) was directly based upon Haarmann's crimes. This film was released in July 1973 and was directed by Ulli Lommel. The Tenderness of the Wolves was both written by and starred Kurt Raab, who cast himself as Fritz Haarmann.[89] German film director Rainer Werner Fassbinder produced the film and also appeared in a minor role as Haarmann's criminal accomplice, Hugo Wittkowski.

- The most recent film to be based upon Haarmann's murder spree, Der Totmacher (The Deathmaker), was released in 1995. This film starred Götz George as Haarmann. Der Totmacher focuses upon the written records of the psychiatric examinations of Haarmann conducted by Ernst Schultze; one of the main psychiatric experts who was to testify at Haarmann's 1924 trial. The plot of Der Totmacher centers around Haarmann's interrogation after his arrest, as he is being interviewed by a court psychiatrist.[90]

Books

- Cawthorne, Nigel; Tibbels, Geoffrey (1993) Killers: The Ruthless Exponents of Murder ISBN 0-7522-0850-0

- Lane, Brian; Gregg, Wilfred (1992) The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers ISBN 978-0-747-23731-0

- Lessing, Theodor (1925) Monsters of Weimar: Haarmann, the Story of a Werewolf ISBN 1-897743-10-6

- Wilson, Colin; Wilson, Damon (2006) The World's Most Evil Murderers: Real-Life Stories of Infamous Killers ISBN 978-1-405-48828-0

See also

References

- ↑ Reading Eagle. Dec. 19, 1924

- 1 2 Monsters of Weimar, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 Real Life Crimes, p. 2650, ISBN 1-85875-440-2.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 23.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 24.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 25.

- ↑ CrimeLibrary.com

- 1 2 Monsters of Weimar, p. 28.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, pp. 29-31.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 31.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 35.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 50.

- ↑ CrimeLibrary.com

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, pp. 50-51.

- 1 2 Monsters of Weimar, p. 80.

- 1 2 A Plague of Murder Chapter 3

- 1 2 Monsters of Weimar, p. 99.

- 1 2 3 Monsters of Weimar, p. 65.

- 1 2 Monsters of Weimar, p. 86.

- 1 2 Monsters of Weimar, p. 60.

- 1 2 Monsters of Weimar, p. 81.

- 1 2 Monsters of Weimar, p. 54.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 83.

- 1 2 3 Monsters of Weimar, p. 37.

- ↑ Real Life Crimes, p. 2652, ISBN 1-85875-440-2.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 41.

- 1 2 Monsters of Weimar, p. 42.

- ↑ trutv.com.

- 1 2 3 The Evening Independent Dec. 19, 1924

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 45.

- ↑ Real Life Crimes, p. 2651, ISBN 1-85875-440-2.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 47.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 84.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, pp. 83-84.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 85.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 89.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 103.

- 1 2 Monsters of Weimar, p. 113.

- 1 2 3 4 The Sunday Morning Star. Dec. 7, 1924

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 123.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 124.

- 1 2 Monsters of Weimar, p. 17.

- ↑ Real Life Crimes, p. 2653, ISBN 1-85875-440-2.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 56.

- 1 2 Monsters of Weimar, p. 64.

- ↑ The Milwaukee Journal Jan. 19, 1933

- ↑ Cannibal Serial Killers ISBN 1-5697-5902-2 p. 225

- 1 2 3 Ludlington Daily News Dec. 7, 1924

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 110.

- ↑ The Montreal Gazette Jul. 16, 1924

- ↑ Lewiston Daily Sun Dec. 6, 1924

- 1 2 The Pittsburg Press Dec. 6, 1924

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, pp. 108-109.

- ↑ St. Petersburg Times. Dec. 7, 1924

- ↑ The Encyclopaedia of Serial Killers ISBN 0-7472-3731-X p. 207

- ↑ Sunday Morning Star Dec. 7, 1924

- 1 2 Reading Eagle Dec. 14, 1924

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 19.

- ↑ Reading Eagle Dec. 19, 1924.

- ↑ Times Daily Dec. 19, 1924

- ↑ Times Daily Dec. 19, 1924.

- ↑

- 1 2 Monsters of Weimar, p. 129.

- ↑ The Sunday Morning Star Dec. 21, 1924

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 145.

- ↑ Reading Eagle Feb. 6, 1925

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Serial Killers ISBN 1-85648-328-2 p. 77

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 67–143.

- 1 2 Southeast Missourian Apr. 15, 1925

- ↑ Prescott Evening Courier Apr. 15, 1925

- ↑ "Execute Three Men In Europe: Fritz Haarmann, Lurer of Youths, Dies on the guillotine". The Florence Times. Hanover, Germany: Google News Archive Search. April 15, 1925. p. 4. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ↑ Gottinger-Tageblatt June. 1, 2012

- ↑ "Report: 'Butcher of Hannover's' head cremated after 89 years". AP News. 24 January 2015.

- ↑ Spiegel.de.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 143.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 152.

- ↑ Gilbert, Alexander. "Fritz Haarmann: The Butcher of Hannover". Crime Library. Retrieved 4 November 2007..

- ↑ Richard Plant, The Pink Triangle, New York, Henry Holt & Co., 1986, p. 45

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 87.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 92.

- 1 2 Monsters of Weimar, p. 94.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 95.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 97.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 107.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 114.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 122.

- 1 2 3 Monsters of Weimar, p. 101.

- ↑ Monsters of Weimar, p. 34.

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0070957/.

- ↑ http://www.cinereel.org/article1427.html.

Cited works and further reading

- Cawthorne, Nigel; Tibbels, Geoff (1993). Killers: The Ruthless Exponents of Murder. London: Boxtree Books. pp. 415–17. ISBN 0-7522-0850-0.

- Lane, Brian; Gregg, Wilfred (1995) [1992]. The Encyclopedia Of Serial Killers. New York City: Berkley Book. pp. 205–06. ISBN 978-0-425-15213-3.

- Lessing, Theodor (1993) [1925]. Monsters of Weimar: Haarmann, the Story of a Werewolf. London: Nemesis Books. pp. 11–156. ISBN 1-897743-10-6.

- Pozsár, Christine; Farin, Michael (2002) [1995]. Die Haarmann-Protokolle. Reinbek: Rowohlt Verlag. ISBN 3-936-29800-9.

- Tatar, Maria (1995). Lustmord. Sexual Murder in Weimar Germany. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-6910-1590-2.

- Wilson, Colin; Wilson, Damon. The World's Most Evil Murderers: Real-Life Stories of Infamous Killers. Bath: Paragon Publishing. pp. 17–20. ISBN 978-1-405-48828-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fritz Haarmann. |

- Fritz Haarmann at CrimeLibrary.com

- Contemporary newspaper account of Haarmann's execution

- Image depicting Haarmann's severed head, preserved at Göttingen medical school until its 2014 cremation