Everything which is not forbidden is allowed

"Everything which is not forbidden is allowed" is a constitutional principle of English law—an essential freedom of the ordinary citizen or subject. The converse principle—"everything which is not allowed is forbidden"—used to apply to public authorities, whose actions were limited to the powers explicitly granted to them by law.[1] The restrictions on local authorities were lifted by the Localism Act 2011 which granted a "general power of competence" to local authorities.

Totalitarian principle

In The Once and Future King, author T. H. White proposed the opposite as the rule of totalitarianism: "Everything which is not forbidden is compulsory."[2] This quote has been suggested as a principle of physics[3] and has been used to describe totalitarian societies such as North Korea.[4]

National traditions

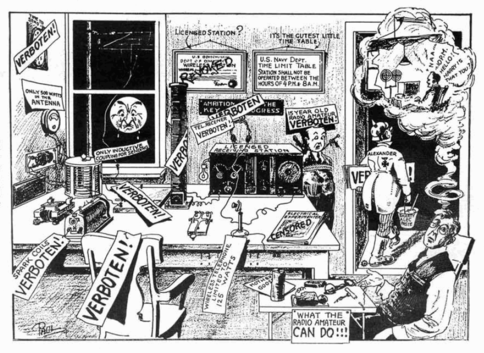

The jocular saying is that, in England, "everything which is not forbidden is allowed", while, in Germany, the opposite applies, so "everything which is not allowed is forbidden". This may be extended to France—"everything is allowed even if it is forbidden"[5]—and Russia where "everything is forbidden, even that which is expressly allowed".[6] While in North Korea it is said that "everything that is not forbidden is compulsory"[4]

The saying about the Germans is at least partially true. In discussion amongst German scholars of German Law an argument often found is that a juristic construction is not applicable since the law doesn't state its existence – even if the law doesn't explicitly state that the construction does not exist. An example for this is the Nebenbesitz (indirect possession of a right by more than one person), which is denied by German courts with the argument that §868 of the Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, which defines indirect possession, doesn't say there could be two people possessing.

It should be noted that, in some languages (notably Scandinavian ones), the distinction between "must not" and "don't have to" is largely left for context to indicate (for example, Norwegian uses "må ikke" for both). This is however not the case in Swedish where "must not" is written "får inte" and "don't have to" is written "måste inte". This may well have implications for how different cultures perceive (and their legal traditions handle) the distinction between them, and between their opposites—"not forbidden" and "obligatory".

See also

References

- ↑ Gordon Slynn Slynn of Hadley, Mads Tønnesson Andenæs, Duncan Fairgrieve (2000), Judicial review in international perspective, Kluwer Law International, p. 256, ISBN 978-90-411-1378-8

- ↑ T. H. White, The Sword in the Stone (book 1 of The Once and Future King), Collins (1938)

- ↑ Stephen Weinberg, "Einstein's Mistakes," in Donald Goldsmith and Marcia Bartusiak (eds.), E: His Life, His Thought and His Influence on Our Culture, Sterling Publishing (2006) p. 312.

- 1 2 Mangaldeep, Nandi triumph, retrieved 29 July 2013

- ↑ Melanie Hawthorne; Sylvie Saillet (2003), A Practical Guide to French Business, ISBN 978-0-595-26462-9

- ↑ Kishor Bhagwati (2007), Managing safety, p. 37, ISBN 978-3-527-31583-3