Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States of America |

|---|

|

|

Preamble and Articles of the Constitution |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

|

| Unratified Amendments |

| History |

| Full text of the Constitution and Amendments |

|

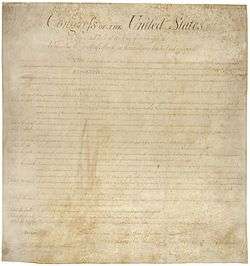

The Tenth Amendment (Amendment X) to the United States Constitution, which is part of the Bill of Rights, was ratified on December 15, 1791.[1] It expresses the principle of federalism, which strictly supports the entire plan of the original Constitution for the United States of America, by stating that the federal government possesses only those powers delegated to it by the United States Constitution. All remaining powers are reserved for the states or the people.

The amendment was proposed by Congress in 1789 during its first term following the Constitutional Convention and ratification of the Constitution. It was considered by many members as a prerequisite of such ratification[2] particularly to satisfy demands by the Anti-Federalism movement that opposed the creation of a stronger U.S. federal government.

In drafting this amendment, its framers had two purposes in mind: first, as a necessary rule of construction; and second, as a reaffirmation of the nature of the federal system of freedom.[3][4]

Text

The full text of the amendment reads as follows:

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.[5]

Drafting and adoption

The Tenth Amendment is similar to an earlier provision of the Articles of Confederation: "Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled."[6] After the Constitution was ratified, South Carolina Representative Thomas Tudor Tucker and Massachusetts Representative Elbridge Gerry separately proposed similar amendments limiting the federal government to powers "expressly" delegated, which would have denied implied powers.[7] James Madison opposed the amendments, stating that "it was impossible to confine a Government to the exercise of express powers; there must necessarily be admitted powers by implication, unless the Constitution descended to recount every minutia."[7] The word "expressly" ultimately did not appear in the Tenth Amendment as ratified, and therefore the Tenth Amendment did not reject the powers implied by the Necessary and Proper Clause.[8]

When he introduced the Tenth Amendment in Congress, James Madison explained that many states were eager to ratify this amendment, despite critics who deemed the amendment superfluous or unnecessary:

I find, from looking into the amendments proposed by the State conventions, that several are particularly anxious that it should be declared in the Constitution, that the powers not therein delegated should be reserved to the several States. Perhaps words which may define this more precisely than the whole of the instrument now does, may be considered as superfluous. I admit they may be deemed unnecessary: but there can be no harm in making such a declaration, if gentlemen will allow that the fact is as stated. I am sure I understand it so, and do therefore propose it.[9]

The states decided to ratify the Tenth Amendment, and thus declined to signal that there are unenumerated powers in addition to unenumerated rights.[10][11] The amendment rendered unambiguous what had previously been at most a mere suggestion or implication.

The phrase "..., or to the people." was appended in handwriting by the clerk of the Senate as the Bill of Rights circulated between the two Houses of Congress.[12][13]

Judicial interpretation

The Tenth Amendment, which makes explicit the idea that the federal government is limited to only the powers granted in the Constitution, has been declared to be a truism by the Supreme Court. In United States v. Sprague (1931) the Supreme Court asserted that the amendment "added nothing to the [Constitution] as originally ratified."

States and local governments have occasionally attempted to assert exemption from various federal regulations, especially in the areas of labor and environmental controls, using the Tenth Amendment as a basis for their claim. An often-repeated quote, from United States v. Darby Lumber, 312 U.S. 100, 124 (1941), reads as follows:

The amendment states but a truism that all is retained which has not been surrendered. There is nothing in the history of its adoption to suggest that it was more than declaratory of the relationship between the national and state governments as it had been established by the Constitution before the amendment or that its purpose was other than to allay fears that the new national government might seek to exercise powers not granted, and that the states might not be able to exercise fully their reserved powers.

Forced participation or commandeering

The Supreme Court rarely declares laws unconstitutional for violating the Tenth Amendment. In the modern era, the Court has only done so where the federal government compels the states to enforce federal statutes. In 1992, in New York v. United States, 505 U.S. 144 (1992), for only the second time in 55 years, the Supreme Court invalidated a portion of a federal law for violating the Tenth Amendment. The case challenged a portion of the Low-Level Radioactive Waste Policy Amendments Act of 1985. The act provided three incentives for states to comply with statutory obligations to provide for the disposal of low-level radioactive waste. The first two incentives were monetary. The third, which was challenged in the case, obliged states to take title to any waste within their borders that was not disposed of prior to January 1, 1996, and made each state liable for all damages directly related to the waste. The Court, in a 6–3 decision, ruled that the imposition of that obligation on the states violated the Tenth Amendment. Justice Sandra Day O'Connor wrote that the federal government can encourage the states to adopt certain regulations through the spending power (e.g. by attaching conditions to the receipt of federal funds, see South Dakota v. Dole, 483 U.S. 203 (1987), or through the commerce power (by directly pre-empting state law). However, Congress cannot directly compel states to enforce federal regulations.

In 1998, the Court again ruled that the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act violated the Tenth Amendment (Printz v. United States, 521 U.S. 898 (1997). The act required state and local law enforcement officials to conduct background checks on people attempting to purchase handguns. Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the majority, applied New York v. United States to show that the law violated the Tenth Amendment. Since the act "forced participation of the State's executive in the actual administration of a federal program", it was unconstitutional.

In 2012, in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (132 S.Ct. 2566 (2011)), Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the Court, held that the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (commonly referred to as the ACA or Obamacare) improperly coerced the States to expand Medicaid. He classified the ACA's language as coercive because it effectively forced States to join the federal bureaucracy by conditioning the continued provision of Medicaid funds on States agreeing to materially alter Medicaid eligibility to include all individuals who fell below 133% of the poverty line.

Commerce clause

In modern times, the Commerce Clause has become one of the most frequently-used sources of Congress's power, and thus its interpretation is very important in determining the allowable scope of federal government.[14]

In the 20th century, complex economic challenges arising from the Great Depression triggered a reevaluation in both Congress and the Supreme Court of the use of Commerce Clause powers to maintain a strong national economy[15]

In Wickard v. Filburn (1942), in the context of World War II, the Court ruled that federal regulations of wheat production could constitutionally be applied to wheat grown for "home consumption" on a farm – that is, wheat grown to be fed to farm animals or otherwise consumed on the farm. The rationale was that a farmer's growing "his own wheat" can have a substantial cumulative effect on interstate commerce, because if all farmers were to exceed their production quotas, a significant amount of wheat would either not be sold on the market or would be bought from other producers. Hence, in the aggregate, if farmers were allowed to consume their own wheat, it would affect the interstate market in wheat.

In Garcia v. San Antonio Metropolitan Transit Authority (1985), the Court changed the analytic framework to be applied in Tenth Amendment cases. Prior to the Garcia decision, the determination of whether there was state immunity from federal regulation turned on whether the state activity was "traditional" for or "integral" to the state government. The Court noted that this analysis was "unsound in principle and unworkable in practice", and rejected it without providing a replacement. The Court's holding declined to set any formula to provide guidance in future cases. Instead, it simply held "...we need go no further than to state that we perceive nothing in the overtime and minimum-wage requirements of the FLSA ... that is destructive of state sovereignty or violative of any constitutional provision." It left to future courts how best to determine when a particular federal regulation may be "destructive of state sovereignty or violative of any constitutional provision."

In United States v. Lopez 514 U.S. 549 (1995), a federal law mandating a "gun-free zone" on and around public school campuses was struck down because, the Supreme Court ruled, there was no clause in the Constitution authorizing it. This was the first modern Supreme Court opinion to limit the government's power under the Commerce Clause. The opinion did not mention the Tenth Amendment, and the Court's 1985 Garcia opinion remains the controlling authority on that subject.

Most recently, the Commerce Clause was cited in the 2005 decision Gonzales v. Raich. In this case, a California woman sued the Drug Enforcement Administration after her medical cannabis crop was seized and destroyed by federal agents. Medical cannabis was explicitly made legal under California state law by Proposition 215; however, cannabis is prohibited at the federal level by the Controlled Substances Act. Even though the woman grew cannabis strictly for her own consumption and never sold any, the Supreme Court stated that growing one's own cannabis affects the interstate market of cannabis. The theory was that the cannabis could enter the stream of interstate commerce, even if it clearly wasn't grown for that purpose and that was unlikely ever to happen (the same reasoning as in the Wickard v. Filburn decision). It therefore ruled that this practice may be regulated by the federal government under the authority of the Commerce Clause.

Federal funding

The federal system limits the ability of the federal government to use state governments as an instrument of the national government, as held in Printz v. United States, 521 U.S. 898 (1997). However, where Congress or the Executive has the power to implement programs, or otherwise regulate, there are, arguably, certain incentives in the national government encouraging States to become the instruments of such national policy, rather than to implement the program directly. One incentive is that state implementation of national programs places implementation in the hands of local officials who are closer to local circumstances. Another incentive is that implementation of federal programs at the state level would in principle limit the growth of the national bureaucracy.

For this reason, Congress often seeks to exercise its powers by offering or encouraging States to implement national programs consistent with national minimum standards; a system known as cooperative federalism. One example of the exercise of this device was to condition allocation of federal funding where certain state laws do not conform to federal guidelines. For example, federal educational funds may not be accepted without implementation of special education programs in compliance with IDEA. Similarly, the nationwide state 55 mph (90 km/h) speed limit, .08 legal blood alcohol limit, and the nationwide state 21-year drinking age were imposed through this method; the states would lose highway funding if they refused to pass such laws (though the national speed limit has since been repealed). See e.g. South Dakota v. Dole, 483 U.S. 203 (1987).

See also

References

- ↑ "The Bill of Rights: A Transcription". United States National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ↑ National Archives. "Bill of Rights". Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ↑ Cooper, Charles. "Essay on the Tenth Amendment:Reserved Powers of the States". Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ↑ Justice Robert F. Utter (2010-07-18). ""Freedom and Diversity in a Federal System: Perspectives on State Constitutions and the Washington Declaration of Rights" by Justice Robert F. Utter". Digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ↑ United States Government Printing Office. "TENTH AMENDMENT – RESERVED POWERS – CONTENTS" (PDF). GPO.gov.

- ↑ "Articles of Confederation from Yale University". Yale Law School Avalon Project. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- 1 2 "House of Representatives, Amendments to the Constitution". University of Chicago. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- ↑ Epps, Garrett. "Constitutional Myth #7: The 10th Amendment Protects 'States' Rights'". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2013-06-26.

- ↑ "Bill of Rights Documents: Document 11: House of Representatives, Amendments to the Constitution". The Founders' Constitution. University of Chicago. 8 June; 21 July; 13, 18–19 August 1789. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ Gibson v. Matthews, 926 F.2d 532, 537 (6th Cir. 1991): "The ninth amendment was added to the Bill of Rights to ensure that the maxim expressio unius est exclusio alterius would not be used at a later time...."

- ↑ Calabresi, Steven; Prakash, Saikrishna (1994). "The President's Power to Execute the Laws". Yale Law Journal. 104.

The message of the Tenth Amendment is that expressio unius est exclusio alterius applies to lists of governmental powers.

- ↑ Rollins, Henry Lawrence. "Henry Speaks On His Consciousness-Expanding Trip to the Library of Congress With Ian MacKaye". Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- ↑ Draft of Bill of Rights, September 9, 1789, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, The Center for Legislative Archives, Senate Revisions to House-passed Amendments to the Constitution

- ↑ Epstein, Richard A. (2014). The Classical Liberal Constitution. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-674-72489-1.

- ↑ Epstein, Richard A. (2014). The Classical Liberal Constitution. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-674-72489-1.

External links

- CRS Annotated Constitution: Tenth Amendment, Cornell's Annotated Constitution

- Tenth Amendment Center works to preserve and protect Tenth Amendment freedoms through information and education. The center serves as a forum for the study and exploration of states’ rights issues, focusing primarily on the decentralization of federal government power.

- Lindner, Doug. Exploring Constitutional Conflicts - explores some of the issues and controversies that surround the US Constitution