George Moore (novelist)

| George Moore | |

|---|---|

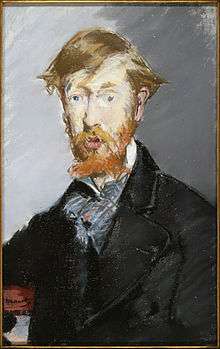

Portrait by Édouard Manet, 1879 | |

| Born |

George Augustus Moore 24 February 1852 Moore Hall, County Mayo, Ireland |

| Died |

21 January 1933 (aged 80) London, England |

| Resting place | Castle Island, County Mayo, Ireland |

| Occupation | short-story writer, poet, art critic, memoirist and dramatist |

| Language | English |

| Alma mater | National Art Training School |

| Period | 1878–1933 |

| Literary movement | Celtic Revival |

| Notable works | Confessions of a Young Man, Esther Waters |

| Relatives |

John Moore (granduncle) Maurice George Moore |

George Augustus Moore (24 February 1852 – 21 January 1933) was an Irish novelist, short-story writer, poet, art critic, memoirist and dramatist. Moore came from a Roman Catholic landed family who lived at Moore Hall in Carra, County Mayo.[1] He originally wanted to be a painter, and studied art in Paris during the 1870s. There, he befriended many of the leading French artists and writers of the day.

As a naturalistic writer, he was amongst the first English-language authors to absorb the lessons of the French realists, and was particularly influenced by the works of Émile Zola.[2] His writings influenced James Joyce, according to the literary critic and biographer Richard Ellmann,[3] and, although Moore's work is sometimes seen as outside the mainstream of both Irish and British literature, he is as often regarded as the first great modern Irish novelist.

Life

Family origins

George Moore's family had lived in Moore Hall, near Lough Carra, County Mayo for almost a century.[4] The house was built by his paternal great-grandfather—also called George Moore—who had made his fortune as a wine merchant in Alicante.[5] The novelist's grandfather was a friend of Maria Edgeworth, and author of An Historical Memoir of the French Revolution.[6] His great-uncle, John Moore, was president of the short-lived Republic of Connacht[7] during the Irish Rebellion of 1798. The novelist's father, George Henry Moore, sold his stable and hunting interests during the Great Irish Famine, and from 1847–1857, served as an Independent Member of Parliament (MP) for Mayo in the British House of Commons.[8] George Henry was renowned as a fair landlord, fought to uphold the rights of tenants,[9] and was a founder of the Catholic Defence Association. His estate consisted of 5000 ha (50 km²) in Mayo, with a further 40 ha in County Roscommon.

Early life

George Moore was born in Moore Hall in 1852. As a child, Moore enjoyed the novels of Walter Scott, which his father read to him.[10] He spent a good deal of time outdoors with his brother, Maurice George Moore, and also became friendly with the young Willie and Oscar Wilde, who spent their summer holidays at nearby Moytura. Oscar was to later quip of Moore: "He conducts his education in public".[11]

His father had again turned his attention to horse breeding and in 1861 brought his champion horse, Croagh Patrick, to England for a successful racing season, together with his wife and nine-year-old son. For a while George was left at Cliff's stables until his father decided to send George to his alma mater facilitated by his winnings. Moore's formal education started at St. Mary's College, Oscott, a Catholic boarding school near Birmingham where he was the youngest of 150 boys. He spent all of 1864 at home, having contracted a lung infection brought about by a breakdown in his health. His academic performance was poor while he was hungry and unhappy. In January 1865, he returned to St. Mary's College with his brother Maurice, where he refused to study as instructed and spent time reading novels and poems.[12] That December the principal, Spencer Northcote, wrote a report that: "he hardly knew what to say about George." By the summer of 1867 he was expelled, for (in his own words) 'idleness and general worthlessness', and returned to Mayo. His father once remarked, about George and his brother Maurice: "I fear those two redheaded boys are stupid", an observation which proved untrue for all four boys.[13]

London and Paris

In 1868, Moore's father was again elected MP for Mayo and the family moved to London the following year. Here, Moore senior tried, unsuccessfully, to have his son follow a career in the military though, prior to this, he attended the School of Art in the South Kensington Museum where his achievements were no better. He was freed from any burden of education when his father died in 1870.[13] Moore, though still a minor, inherited the family estate that was valued at £3,596. He handed it over to his brother Maurice to manage and in 1873, on attaining his majority, moved to Paris to study art. It took him several attempts to find an artist who would accept him as a pupil. Monsieur Jullian, who had previously been a shepherd and circus masked man, took him on for 40 francs a month.[14] At Académie Jullian he met Lewis Weldon Hawkins who became Moore's flat-mate and whose trait, as a failed artist, show up in Moore's own characters.[13] He met many of the key artists and writers of the time, including Pissarro, Degas, Renoir, Monet, Daudet, Mallarmé, Turgenev and, above all, Zola, who was to prove an influential figure in Moore's subsequent development as a writer.

While still in Paris his first book, a collection of lyric poems called The Flowers of Passion, was self-published in 1877. The poems were derivative, maliciously reviewed by the critics who were offended by some of the depravities in store for moralistic readers and was withdrawn by Moore.[15][16] He was forced to return to Ireland in 1880 to raise £3,000 to pay debts incurred on the family estate due to his tenants refusing to pay their rent and the drop in agricultural prices.[16] During his time back in Mayo, he gained a reputation as a fair landlord, continuing the family tradition of not evicting tenants and refusing to carry firearms when travelling round the estate. While in Ireland, he decided to abandon art and move to London to become a professional writer. There he published his second poetry collection, Pagan Poems, in 1881. These early poems reflect his interest in French symbolism and are now almost entirely neglected. In 1886 Moore published Confessions of a Young Man, a lively and energetic memoir about his 20s spent in Paris and London among bohemian artists.[17] It contains a substantial amount of literary criticism for which it has received a fair amount of praise,[17][18] for instance The Modern Library chose it in 1917 to be included in the series as "one of the most significant documents of the passionate revolt of English literature against the Victorian tradition."[18]

Controversy in England

Moore as caricatured by Walter Sickert in Vanity Fair, January 1897

During the 1880s, Moore began work on a series of novels in a realist style. His first novel, A Modern Lover (1883) was a three-volume work, as preferred by the circulating libraries, and deals with the art scene of the 1870s and 1880s in which many characters are identifiably real.[19] The circulating libraries in England banned the book because of its explicit portrayal of the amorous pursuits of its hero. At this time the British circulating libraries, such as Mudie's Select Library, controlled the market for fiction and the public, who paid fees to borrow their books, expected them to guarantee the morality of the novels available.[20] His next book, a novel in the realist style, A Mummers Wife (1885) was also regarded as unsuitable by Mudie's and W H Smith refused to stock it on their news-stalls. Despite this, during its first year of publication the book was in its fourteenth edition mainly due to the publicity stirred up by its opponents.[21] The French newspaper Le Voltaire published it in serial form as La Femme du cabotin in July–October 1886.[22] His next novel A Drama in Muslin was banned by Mudie's and Smith's. In response Moore declared war on the circulating libraries by publishing two provocative pamphlets; Literature at Nurse and Circulating Morals. In these, he complained that the libraries profit from salacious popular fiction while refusing to stock serious literary fiction.

Moore's publisher Henry Vizetelly began to issue unabridged mass-market translations of French realist novels that endangered the moral and commercial influence of the circulating libraries around this time. In 1888, the circulating libraries fought back by encouraging the House of Commons to implement laws to stop "the rapid spread of demoralising literature in this country". However, Vizetelly was brought to court by the National Vigilance Association (NVA) for "obscene libel". The charge arose due to the publication of the English translation of Zola's La Terre. A second case was brought the following year in order to force implementation of the original judgement and to remove all of Zola's works. This led to the 70-year-old publisher becoming involved in the literary cause.[23] Throughout Moore stayed loyal to Zola's publisher, and on 22 September 1888, about a month before the trial, wrote a letter that appeared in the St. James Gazette. In it Moore suggested that it was improper for Vizetelly's fate to be determined by a jury of twelve tradesmen, explaining that it would be preferable to be judged by three novelists. Moore pointed out that the NVA could make the same claims against such books as Madame Bovary and Gautier's Mademoiselle de Maupin, as their morals are equivalent to Zola's, though their literary merits might differ.[24]

Because of his willingness to tackle such issues as prostitution, extramarital sex and lesbianism, Moore's novels were initially met with disapproval. However, as the public's taste for realist fiction grew, this subsided. Moore began to find success as an art critic with the publication of books such as Impressions and Opinions (1891) and Modern Painting (1893)—which was the first significant attempt to introduce the Impressionists to an English audience. By this time Moore was first able to live from the proceeds of his literary work.

Other realist novels by Moore from this period include A Drama in Muslin (1886), a satiric story of the marriage trade in Anglo-Irish society that hints at same-sex relationships among the unmarried daughters of the gentry, and Esther Waters (1894), the story of an unmarried housemaid who becomes pregnant and is abandoned by her footman lover. Both of these books have remained almost constantly in print since their first publication. His 1887 novel A Mere Accident is an attempt to merge his symbolist and realist influences. He also published a collection of short stories: Celibates (1895).

Dublin and the Celtic Revival

In 1901, Moore returned to Ireland to live in Dublin at the suggestion of his cousin and friend, Edward Martyn. Martyn had been involved in Ireland's cultural and dramatic movements for some years, and was working with Lady Gregory and William Butler Yeats to establish the Irish Literary Theatre. Moore soon became deeply involved in this project and in the broader Irish Literary Revival. He had already written a play, The Strike at Arlingford (1893), which was produced by the Independent Theatre. The play was the result of a challenge between Moore and George Robert Sims over Moore's criticism of all contemporary playwrights in Impressions and Opinions. Moore won the one hundred pound bet made by Sims for a stall to witness an "unconventional" play by Moore, though Moore insisted the word "unconventional" be excised.[25]

The Irish Literary Theatre staged his satirical comedy The Bending of the Bough (1900), adapted from Martyn's The Tale of a Town, originally rejected by the theatre but unselfishly given to Moore for revision, and Martyn's Maeve. Staged by the company who would later become the Abbey Theatre, The Bending of the Bough was a historically important play and introduced realism into Irish literature. Lady Gregory wrote that it: "hits impartially all round".[26] The play was satire on Irish political life, and as it was unexpectedly nationalist, was considered the first to deal with a vital question that had appeared in Irish life.[26] Diarmuid and Grania, a poetic play in prose co-written with Yeats in 1901, was also staged by the theatre,[27] with incidental music by Elgar.[28] After this production Moore took up pamphleteering on behalf of the Abbey, and parted company with the dramatic movement.[26]

Moore published two books of prose fiction set in Ireland around this time; a second book of short stories, The Untilled Field (1903) and a novel, The Lake (1905). The Untilled Field deal with themes of clerical interference in the daily lives of the Irish peasantry, and of the issue of emigration. The stories were originally written for translation into Irish, in order to serve as models for other writers working in the language. Three of the translations were published in the New Ireland Review, but publication was then paused due to a perceived anti-clerical sentiment. In 1902 the entire collection was translated by Tadhg Ó Donnchadha and Pádraig Ó Súilleabháin, and published in a parallel-text edition by the Gaelic League as An-tÚr-Ghort. Moore later revised the texts for the English edition. These stories were influenced by Turgenev's A Sportsman's Sketches, a book recommended to Moore by W. K. Magee, a sub-librarian of the National Library of Ireland, and had earlier suggested that Moore "was best suited to become Ireland's Turgenev".[29] The tales are recognised by some as representing the birth of the Irish short story as a literary genre.[3]

In 1903, following a disagreement with his brother Maurice over the religious upbringing of his nephews, Moore declared himself to be Protestant. His conversion was announced in a letter to the Irish Times newspaper.[30] Moore remained in Dublin until 1911. In 1914, he published a gossipy, three-volume memoir of his time there under the collective title Hail and Farewell, which entertained its readers but infuriated former friends. Moore himself said of these memoirs, "Dublin is now divided into two sets; one half is afraid it will be in the book, and the other is afraid that it won't".[31]

In his later years he was increasingly friendless, having quarreled bitterly with Yeats and Osborn Bergin, among others: Oliver St. John Gogarty said: "It was impossible to be a friend of his, because he was incapable of gratitude".[32]

Later life

Moore returned to London in 1911, where, with the exception of frequent trips to France, he was to spend much of the rest of his life. In 1913, he traveled to Jerusalem to research for his next novel, The Brook Kerith (1916). The book saw Moore once again embroiled in controversy, as it was based on the supposition that a non-divine Christ did not die on the cross but instead was nursed back to health.[3] Other books from this period include a further collection of short-stories called A Storyteller's Holiday (1918), a collection of essays called Conversations in Ebury Street (1924) and a play, The Making of an Immortal (1927). Moore also spent considerable time revising and preparing his earlier writings for new editions.[3]

Partly due to Maurice's pro-treaty activity, Moore Hall was burnt by anti-treaty forces in 1923, during the final months of the Irish Civil War.[33] Moore eventually received compensation of £7,000 from the government of the Irish Free State. By this time George and Maurice had become estranged, mainly because of an unflattering portrait of the latter which appeared in Hail and Farewell. Tension also arose as a result of religious differences: Maurice frequently made donations to the Roman Catholic Church from estate funds.[34] Moore later sold a large part of the estate to the Irish Land Commission for £25,000.

Moore was friendly with many members of the expatriate artistic communities in London and Paris, and had a long-lasting relationship with Maud, Lady Cunard. Moore took a special interest in the education of Maud's daughter, the well-known publisher and art patron, Nancy Cunard.[35] It has been suggested that Moore, rather than Maud's husband, Sir Bache Cunard, was Nancy's father,[36] but this is not generally credited by historians, and it is not certain that Moore's relationship with Nancy's mother was ever more than platonic.[37] Moore was believed by some to be impotent and was described as "one who told but didn't kiss".[38] Moore's last novel, Aphroditis in Aulis, was published in 1930.[3]

He died at his home at Ebury Street in the London district of Belgravia in early 1933, leaving a fortune of £70,000. He was cremated in London at a service attended by Ramsay MacDonald among others. An urn containing his ashes was interred on Castle Island in Lough Carra in view of the ruins of Moore Hall.[3]

Works

- Flowers of Passion London: Provost & Company, 1878

- Martin Luther: A Tragedy in Five Acts London: Remington & Company, 1879

- Pagan Poems London: Newman & Company, 1881

- A Modern Lover London: Tinsley Brothers, 1883

- A Mummer's Wife London: Vizetelly & Company, 1885

- Literature at Nurse London: Vizetelly & Company, 1885

- A Drama in Muslin London: Vizetelly & Company, 1886

- A Mere Accident London: Vizetelly & Company, 1887

- Parnell and His Island London; Swan Sonnenshein Lowrey & Company, 1887

- Confessions of a Young Man Swan Sonnenshein Lowrey & Company, 1888

- Spring Days London: Vizetelly & Company, 1888

- Mike Fletcher London: Ward & Downey, 1889

- Impressions and Opinions London; David Nutt, 1891

- Vain Fortune London: Henry & Company, 1891

- Modern Painting London: Walter Scott, 1893

- The Strike at Arlingford London: Walter Scott, 1893

- Esther Waters London: Walter Scott, 1894

- Celibates London: Walter Scott, 1895

- Evelyn Innes London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1898

- The Bending of the Bough London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1900

- Sister Theresa London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1901

- The Untilled Field London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1903

- The Lake London: William Heinemann, 1905

- Memoirs of My Dead Life London: William Heinemann, 1906

- The Apostle: A Drama in Three Acts Dublin: Maunsel & Company, 1911

- Hail and Farewell London: William Heinemann, 1911, 1912, 1914

- The Apostle: A Drama in Three Acts Dublin: Maunsel & Company, 1911

- Elizabeth Cooper Dublin: Maunsel & Company, 1913

- Muslin London: William Heinemann, 1915

- The Brook Kerith: A Syrian Story London: T. Warner Laurie, 1916

- Lewis Seymour and Some Women New York: Brentano's, 1917

- A Story-Teller's Holiday London: Cumann Sean-eolais na hÉireann (privately printed), 1918. This work contains the story later re-published in the collection Celibate Lives, 1927, as the short story "The Singular Life of Albert Nobbs" which was made into a 2011 movie, Albert Nobbs, starring Glenn Close.

- Avowals London: Cumann Sean-eolais na hÉireann (privately printed), 1919

- The Coming of Gabrielle London: Cumann Sean-eolais na hÉireann (privately printed), 1920

- Heloise and Abelard London: Cumann Sean-eolais na hÉireann (privately printed), 1921

- In Single Strictness London: William Heinemann, 1922

- Conversations in Ebury Street London: William Heinemann, 1924

- Pure Poetry: An Anthology London: Nonesuch Press, 1924

- The Pastoral Loves of Daphnis and Chloe London: William Heinemann, 1924

- Daphnis and Chloe, Peronnik the Fool New York: Boni & Liveright, 1924

- Ulick and Soracha London: Nonesuch Press, 1926

- Celibate Lives London: William Heinemann, 1927 (This collection and his previous work A Story-Teller's Holiday both include the short story "The Singular Life of Albert Nobbs" which was made into a movie, with Glenn Close.)

- The Making of an Immortal New York: Bowling Green Press, 1927

- The Passing of the Essenes: A Drama in Three Acts London: William Heinemann, 1930

- Aphrodite in Aulis New York: Fountain Press, 1930

- A Communication to My Friends London: Nonesuch Press, 1933

- Diarmuid and Grania: A Play in Three Acts Co-written with W.B. Yeats, Edited by Anthony Farrow, Chicago: De Paul, 1974

Letters

- Moore Versus Harris Detroit: privately printed, 1921

- Letters to Dujardin New York: Crosby Gaige, 1929

- Letters of George Moore Bournemouth: Sydenham, 1942

- Letters to Lady Cunard Ed. Rupert Hart-Davis. London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1957

- George Moore in Transition Ed. Helmut E. Gerber, Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1968

Notes

- ↑ Moore Hall

- ↑ Moran, Maureen, (2006), Victorian Literature And Culture p. 145. ISBN 0-8264-8883-8

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gilcher, Edwin (September 2004; online edn, May 2006) "Moore, George Augustus (1852–1933)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35089, retrieved 2008-01-07 (Subscription required)

- ↑ Frazier (2000), p. 11

- ↑ Coyne, Kevin. "The Moores of Moorehal". Mayo Ireland Ltd. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ↑ Bowen, Elizabeth (1950). Collected Impressions. Longmans Green, p. 163. ISBN 0-404-20033-8

- ↑ Frazier (2000), pp. 1–5.

- ↑ Jeffares (1965), p. 7.

- ↑ Frazier (2000), pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Jernigan, Jay. "The Forgotten Serial Version of George Moore's Esther Waters". Nineteenth-Century Fiction, Vol. 23, No. 1, June, 1968. pp. 99-103.

- ↑ Schwab, Arnold T. Review of "George Moore: A Reconsideration", by Brown, Malcolm. Nineteenth-Century Fiction, Vol. 10, No. 4, March, 1956. pp. 310-314.

- ↑ Frazier (2002), pp. 14–16.

- 1 2 3 Farrow (1978), pp. 11-14.

- ↑ Frazier (2000), pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Farrow (1978), p. 22.

- 1 2 Jeffares (1965), pp. 8–9.

- 1 2 Arnold Bennett. Fame and fiction. G. Richards, 1901. Page 236+

- 1 2 Quote by Floyd Dell in "Introduction" to Confessions of a Young Man by George Moore. The Modern Library, 1917.

- ↑ Farrow (1978), p. 31.

- ↑ Frazier (2000), pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Peck (1898), pp. 90–95.

- ↑ Pierse, Mary (2006). George Moore: Artistic Visions and Literary Worlds. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Press. p. 56. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ↑ Sloan (2003), pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Frazier (2000), pp. 173–174.

- ↑ Morris, Lloyd R. (1917), p. 113.

- 1 2 3 Morris (1917), pp. 114–115.

- ↑ Morris (1917), p. 92.

- ↑ Moore, Jerrold N. Edward Elgar: a creative life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984, p. 178. ISBN 0-19-315447-1

- ↑ Frazier (2000), pp. 306, 326.

- ↑ Frazier (2000), p. 331.

- ↑ Galbraith (27 June 1908). "LITERARY LONDON'S CURRENT GOSSIP; George Moore's Book of Criticisms of Irish Affairs -- Literary Women and the Suffrage". New York Times. Retrieved 1 January 2008.

- ↑ Gogarty, Oliver St John. As I was going down Sackville Street, Penguin, 1954 pg. 262

- ↑ Frazier (2000), p. 434.

- ↑ Frazier (2000), pp. 331, 360–363, 382–389.

- ↑ "Nancy Cunard, 1896-1965: Biographical Sketch". Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin. 30 June 1990. Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ↑ "George Moore: Life". Princess Grace Irish Library (Monaco). Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ↑ Marcus, Jane. "Cunard, Nancy Clara (1896–1965)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, September 2010; accessed 16 March 2011. (subscription required)

- ↑ Lyttelton, Letters of 23 February 1956 and 4 December 1958

Sources

- Farrow, Anthony (1978). George Moore. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-6685-5.

- Frazier, Adrian (2000). George Moore, 1852–1933. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08245-2.

- Hone, Joseph (1936). The Life of George Moore. London: Victor Gollancz.

- Igoe (1994). A Literary Guide to Dublin. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-69120-9.

- Jeffares, A. Norman (1965). George Moore. London: The British Council & National Book League.

- Lacey, Brian (2008). Queer Creatures: A History of Homosexuality in Ireland. Dublin: Wordwell Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-905569-23-6.

- Lyttelton, George; Rupert Hart-Davis (1978). The Lyttelton Hart-Davis Letters, Vol 1 (1955-6 letters). London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-3478-X.

- Lyttelton, George; Rupert Hart-Davis (1981). The Lyttelton Hart-Davis Letters, Vol 3 (1958 letters). London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-3770-3.

- Morris, Lloyd R. (1917). The Celtic Dawn: A Survey of the Renascence in Ireland 1889–1916. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- Peck, Harry Thurston (1898). The Personal Equation. New York & London: Harper & Brothers Publishers.

- Sloan, John (2003). Oscar Wilde. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-284064-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to George Moore. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: George Augustus Moore |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: George Moore (novelist) |

- Works by George Moore at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about George Moore at Internet Archive

- Works by George Moore at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Brook Kerith by George Moore, 1916

- George Moore at the Princess Grace Irish Library (archived link)