Hieronymus Fabricius

| Hieronymus Fabricius | |

|---|---|

|

Girolamo Fabrizi d' Acquapendente | |

| Born |

May 20, 1537 Acquapendente |

| Died |

May 21, 1619 (aged 82) Padua |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Fields | Anatomy |

| Doctoral advisor | Gabriele Falloppio |

| Doctoral students |

William Harvey Adriaan van den Spieghel Johannes Heurnius Jan Jesenius Salomon Alberti |

Hieronymus Fabricius or Girolamo Fabrizio, known also by his full Latin and Italian names, Fabricus ab Aquapendente or Girolamo Fabrizi d'Acquapendente, (1537–1619) was a pioneering anatomist and surgeon known in medical science as "The Father of Embryology."

Life and accomplishments

Born in Acquapendente, Latium, Fabricius studied at the University of Padua, receiving a Doctor of Medicine degree in 1559 under the guidance of Gabriele Falloppio. He was a private teacher of anatomy in Padua, 1562–1565,[1] and in 1565, became professor of surgery and anatomy at the university, succeeding Falloppio.[2][3]

In 1594 he revolutionized the teaching of anatomy when he designed the first permanent theater for public anatomical dissections.[2] Julius Casserius (1552–1616) of Piacenza was among Fabricius' students.[4] William Harvey (1578–1657) and Adriaan van den Spiegel (1578–1625) also studied under Fabricius, beginning around 1598. Julius Casserius would later succeed Fabricius as Professor of Anatomy at the University of Padua in 1604, and Adriaan van den Spiegel succeeded Casserius in that position in 1615.[4]

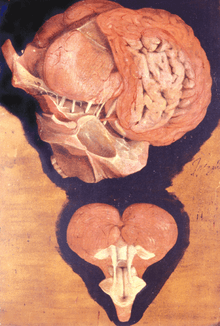

By dissecting animals, Fabricius investigated the formation of the fetus, the structure of the esophagus, stomach and intestines, and the peculiarities of the eye, the ear, and the larynx. He was the first to describe the membranous folds that he called "valves" in the interior of veins. These valves are now understood to prevent retrograde flow of blood within the veins, thus facilitating antegrade flow of blood towards the heart, though Fabricius did not understand their role at that time.

In his Tabulae Pictae, first published in 1600, Fabricius described the cerebral fissure separating the temporal lobe from the frontal lobe.[5] However, Fabricius' discovery was not recognized until recently. Instead, Danish anatomist Caspar Bartholin credits Franciscus Sylvius with the discovery, and Bartholin's son Thomas named it the Sylvian fissure in the 1641 edition of the textbook Institutiones anatomicae.[6]

The Bursa of Fabricius (the site of hematopoiesis in birds) is named after Fabricius. A manuscript entitled De Formatione Ovi et Pulli, found among his lecture notes after his death, was published in 1621. It contains the first description of the bursa.[7]

Fabricius contributed much to the field of surgery. Though he never actually performed a tracheotomy, his writings include descriptions of the surgical technique. He favored using a vertical incision and was the first to introduce the idea of a tracheostomy tube. This was a straight, short cannula that incorporated wings to prevent the tube from disappearing into the trachea. He recommended the operation only as a last resort, to be used in cases of airway obstruction by foreign bodies or secretions. Fabricius' description of the tracheotomy procedure is similar to that used today.

Julius Casserius published his own writings regarding technique and equipment for tracheotomy.[4] Casserius recommended using a curved silver tube with several holes in it. Marco Aurelio Severino (1580–1656), a skilful surgeon and anatomist, performed at least one tracheotomy during a diphtheria epidemic in Naples in 1610, using the vertical incision technique recommended by Fabricius.[8]

Books

- Pentateuchos chirurgicum (1592).

- De Visione, Voce, Auditu. Venedig, Belzetta. 1600.

- De formato foetu. 1600.

- De Venarum Ostiolis. 1603

- De brutorum loquela (1603)

- De locutione et ejus instrumentis tractatus. 1603.

- Tractatus anatomicus triplex quorum primus de oculo, visus organo. Secundus de aure, auditus organo. Tertius de laringe, vociis organo admirandam tradit historiam, actiones, utilitates magno labore ac studio (1613).

- De musculi artificio: de ossium articolationibus (1614).

- De respiratione et eius instrumentis, libri duo (1615).

- De tumoribus (1615)

- De gula, ventriculo, intestinis tractatus (1618).

- De motu locali animalium secundum totum, nempe de gressu in genere (1618).

- De totius animalis integumentis (1618)

- De formatione Ovi et Pulli (posthum 1621, aber vor De formato foetu entstanden)[9]

- Opera chirurgica. Quorum pars prior pentatheucum chirurgicum, posterior operationes chirurgicas continet ... Accesserunt Instrumentorum, quae partim autori, partim alii recens invenere, accurata delineatio. Item, De abusu cucurbitularum in febribus putridis dissertatio, e Musaeo ejusdem (posthum 1623).

- Tractatus De respiratione & eius instrumentis. Ventriculo intestinis, & gula. Motu locali animalium, secundum totum. Musculi artificio, & ossium dearticulationibus (posthum 1625).

See also

.jpg)

References

- ↑ http://galileo.rice.edu/Catalog/NewFiles/fabrici.html

- 1 2 Sean B. Smith; Veronica Macchi; Anna Parenti; Raffaele De Caro (2004). "Hieronymous Fabricius Ab Acquapendente (1533–1619)". Clinical Anatomy. 17 (7): 540–543. doi:10.1002/ca.20022. PMID 15376290.

- ↑ http://www.cartage.org.lb/en/themes/biographies/MainBiographies/F/Fabricius/1.html

- 1 2 3 Julius Casserius (Giulio Casserio) and Daniel Bucretius (1632). Tabulae anatomicae LXXIIX … Daniel Bucretius … XX. que deerant supplevit & omnium explicationes addidit (in Latin). Francofurti: Impensis & coelo Matthaei Meriani. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ Collice M, Collice R, Riva A (2008). "Who discovered the sylvian fissure?". Neurosurgery. 63 (4): 623–628. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000327693.86093.3F. PMID 18981875.

- ↑ Caspar Bartholini (1641). Thomas Bartholin, ed. Institutiones anatomicae, novis recentiorum opinionibus and observationibus quarum innumerae hactenus editae non sunt, figurisque auctae ab auctoris filio Thoma Bartholino (in Latin). Lugdunum Batavorum: Apud Franciscum Hackium.

- ↑ Adelman HB (1967). The Embryological Treatises of Hieronymus Fabricius of Aquapendente: The Formation of the Egg and of the Chick (De Formatione Ovi et Pulli), The Formed Fetus (De Formato Foetu). 1. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 147–191. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ Armytage WHG (1960). "Giambattista Della Porta and the segreti". British Medical Journal. 1 (5179): 1129–1130. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5179.1129. PMC 1966956

.

. - ↑ Hilary Gilson in: The Embryo Project Encyclopedia

Further reading

- Smith, Sean B. (2006). "From Ars to Scientia: the revolution of anatomic illustration". Clinical Anatomy. 19 (4): 382–8. doi:10.1002/ca.20307. PMID 16570293.

- Antonello, A.; Bonfante, L.; Bordin, V.; Calò, L.; Favaro, S.; Rippa-Bonati, M.; D'Angelo, A. (1997). "The Bursa of Hieronymus Fabrici d'Acquapendente: Past and Present of an Anatomical Structure". American Journal of Nephrology. 17 (3-4): 248–51. doi:10.1159/000169109. PMID 9189242.

- Glick, Bruce (1991). "Historical perspective: the bursa of Fabricius and its influence on B-cell development, past and present". Veterinary immunology and immunopathology. 30 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1016/0165-2427(91)90003-U. PMID 1781155.

- Brandt, L; Goerig, M (1986). "Die Geschichte der Tracheotomie. I" [The history of tracheotomy. I]. Der Anaesthesist. 35 (5): 279–83. PMID 3526969.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Girolamo Fabrici. |

- "Some places and memories of Hieronymus Fabricius". The History of Medicine Topographical Database (HIMETOP). n.d.