Gravikord

The gravikord is a modern, 24 string, electric double bridge-harp invented by Robert Grawi in 1986, which is closely related to both the West African kora and the kalimba. It was designed to employ a separated double tonal array structure making it possible to easily play cross-rhythms in a polyrhythmic musical style in a modern electro-acoustic instrument. There is a similar instrument, also developed by Grawi, the gravi-kora, which is tuned identically to a traditional 21 string African kora.

Description

The gravikord is a new instrument developed on the basis of the West African kora. It is made of welded stainless steel tubing, with 24 nylon strings but no resonating gourd or skin. The bridge is made from a machined synthetic material with an integral piezo-electric sensor. Two handles located in elevation near the middle of the bridge allow holding the instrument. The bridge is curved to follow the arc of a strum from the hands which hold the shortened raised handles directly in the palms. A metal crossbar at the top of the bridge functions as a mechanical tone control and bridge stabilizer. The instrument connects to an amplifier like an electric guitar.

The playing technique is similar to that of the kora: the player plucks the strings with the thumb and index finger of each hand. Because each hand can play "with" or "against" each other, simple techniques can produce music of great rhythmic complexity. The tuning of the gravikord is not the same as a traditional Kora, and playing techniques are not directly compatible.

African roots

Because of the deep cultural significance of cross-rhythms to Sub-Saharan African music, several instruments have evolved there which are constructed in such a way as to more easily generate cross-rhythms. These instruments organize the notes in a uniquely divided alternate array – not in the straight linear bass to treble structure that is so common to many western instruments such as the piano, harp, marimba, etc.... Instruments such as the West African kora, and Doussn'gouni, part of the harp-lute family of instruments, and thumb piano type instruments such as the kalimba and mbira also have this separated double tonal array structure.

On these instruments one hand of the musician is not primarily in the bass nor the other primarily in the treble, but both hands can play freely across the entire tonal range of the instrument. Also the fingers of each hand can play separate independent rhythmic patterns and these can easily cross over each other from treble to bass and back, either smoothly or with varying amounts of syncopation. This can all be done within the same tight tonal range, without the left and right hand fingers ever physically encountering each other. These simple rhythms will interact musically to produce complex cross rhythms including repeating on beat/off beat pattern shifts that would be very difficult to create by any other means. This characteristically African structure allows often simple playing techniques to combine with each other and produce polyrhythmic music of great beauty and complexity.

History

Created by Robert Grawi to satisfy the need for an instrument easier to play polyrhythms on than the guitar, its design evolved over several years. During 1973 - 74 the first model made was acoustic having a bamboo and fiberglass basket resonator with animal skin head and large bamboo neck. Although taking inspiration from the West African kora, these first gravikords already differed from the kora by having the tuning mechanisms removed from the neck and placed at the base, and an extensively re-designed bridge which also featured a kalimba incorporated into it that could be played simultaneously with the strings. Its tuning also differed from the kora as it had 25 strings that were tuned symmetrically using a variation of the Hugh Tracey kalimba tuning system as a basis that he thought would be more open to western musicians. Several one of a kind prototypes were also created during this period using wood, aluminum, and other materials, also having different features including stereo output and variable pitch.[1]

As noted in the book Gravikords, Whirlies and Pyrophones by Bart Hopkin – "The design quickly evolved to a more distinctive form. In today's Gravikord the body is made entirely of welded stainless steel tubing, lightweight but strong. There is no resonator; the tones of the twenty-four strings are amplified by means of a piezo-electric pickup in the bridge...The design is thoroughly ergonomic, made for natural and comfortable playing in a sitting or standing position." [2]

Interest in the instrument was shown by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, which included it in the show "Enduring Rhythms" (New York City, October 3, 1996 - August 3, 1997). In an article about this exhibit from The New York Times, Rita Reif writes "Some of the most innovative instruments in the show come from the 20th century when African rhythms became part of jazz, rock, pop, and Latin American dance music as well as gospel and even classical music. The show stoppers include a Gravikord, an electronically amplified stringed instrument that sounds like an earthy harp. In their shapes and sounds, Mr. Moore (curator of the show) said, these instruments also represent a kind of continuity in 'the layered rhythms, the mixed timbres, and all that movement which is so African.'"[3]

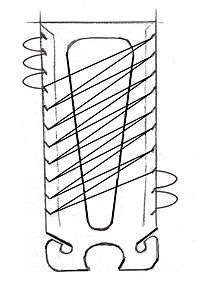

The notability of the instrument was also featured in an article by Tom Mulhern in Guitar Player Magazine –"Even though the Gravikord has a high-tech, modern-sculpture look, it actually has its roots in the African kora, a double strung harp... polyrhythmic music, plus the sound of the Japanese koto, African kalimba (thumb piano) and the African kora...he (Grawi) began experimenting with bamboo double-strung harps that would allow him to perform separate melodies or accompaniments with each hand. Influences range from jazz, Dixieland, to Balinese gamelan and American folk music." This article also includes a technical description of the instrument as well as a patent drawing of the Gravikord.[4]

In an article by Elvis Costello in Vanity Fair he places the recording Gravikords, Whirlies and Pryophones in a list of the finest 500 albums of all time that should be in any audiophile's collection.[5]

Tuning

The gravikord is tuned to a diatonic scale. Its standard scale is in the key of G major/E minor. It has 24 strings, 12 strings on each side, and is structured like an extended Hugh Tracey kalimba, an already westernized African Instrument. The range of notes on both sides are the same and tuning is strictly in an alternate arrangement (except for the lowest bass note), so that the playing is equivalent between the left and right hands. This is reflected in the way the holes are drilled in the neck and the choice of string lengths and weights. A constant finger picking pattern will produce a constant musical pattern throughout the instruments range.

Throughout the playing range the notes of a scale rise strictly alternately and symmetrically, always right, left, right, left, etc. making all the intervals of adjacent strings on each side of the bridge in major or minor thirds. Directly opposite strings are consecutive notes in a scale. Octaves switch sides and are always in a constant spacing. Like on the kora, the player tunes the instrument before playing in the scale he wants.

Gravikord general diatonic tuning:

Left: Sol1, Fa2, La2, Do3, Mi3, Sol3, Ti3, Re4, Fa4, La4, Do5, Mi5.

Right: Do2, Mi2, Sol2, Ti2, Re3, Fa3, La3, Do4, Mi4, Sol4, Ti4, Re5.

Tuning in G major / E minor:

Left Hand: D, C, E, G, B, D, F#, A, C, E, G, B.

Right: G, B, D, F#, A, (middle)C, E, G, B, D, F#, A.

The gravi-kora

Although the gravikord is closely related to the African kora, the musical knowledge of griots and traditional kora players does not directly transfer to gravikord playing. The notes are not where they expect them to be and the bridge and hand playing positions are also different. For these musicians the gravi-kora was developed by Robert Grawi.

The gravi-kora is set up tonally just like traditional koras. It has 21 strings, 11 on left hand, and 10 on right hand side. The instrument is held by hooking the smallest fingers around the long handles which are positioned below the straight sided bridge. The hand placement is above these handles which enables easy string muting while playing with the hand pads. But the range of notes is not the same on both sides of the bridge. The left side is shifted more to the bass register starting with a cluster of the four lowest notes together. The right side is skewed more to the treble, ending with a cluster of the three highest notes on the right side. This is reflected in the way the holes for the strings are drilled in the neck, and the length and weight of strings used. This results in a unique asymmetric layout of tones where most of the strings directly opposite each other in the middle section of the bridge are tuned in octaves except for the bass cluster in the left hand and the treble cluster in the right. This is a standard popular kora tuning.

Gravi-kora general diatonic tuning:

Left: Fa1, Do2, Re2, Mi2, Sol2, Ti2, Re3, Fa3, La3, Do4, Mi4.

Right: Fa2, La2, Do3, Mi3, Sol3, Ti3, Re4, Fa4, Sol4, La4.

Tuning in F major / D minor:

Left Hand: F, C, D, E, G, Bb, D, F, A, C, E.

Right: F, A, (middle)C, E , G, Bb, D, F, G, A.

Although to the casual observer these two instruments look very much alike, the playing experience and the advanced techniques developed by the musicians dedicated to each are very different.

Chromatic playing

Although both instruments are tuned normally to a diatonic scale, on slower pieces, accidentals can be created by sharping individual notes. This is accomplished by pushing and tensioning the section of the string behind the bridge with one finger while playing the string normally. This is similar to a technique used in Japanese koto playing. For faster chromatic pieces a pedal called a pitch shifter can be used to make the instrument fully chromatic. The pedal can be set to momentarily jump shift the entire instrument's tuning one-half step up or down, or it can be set on continuous pitch shift change which enables playing the instrument in dobro, slide guitar, or pedal steel guitar styles.

Effects

Since the instruments produce no conflicting acoustic sound, the gravikord and the gravi-kora can be easily played with all kinds of guitar effects: vibrato, delay, distortion, reverb units, wah-wah pedals, or pitch shifters that allow chromatic playing.

Musical notation

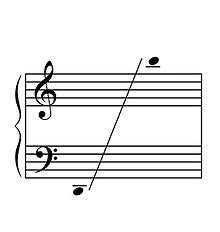

Gravikord

Music for the gravikord can be written in the normal grand staff method using the G clef and F clef.

Also people who do not know music theory can play standard music scores. The gravikord has a property that simplifies the reading of musical notation and the transposition of music written in other key signatures for playing on the instrument. It can be done directly from the music using a mental method. Because of its double structure and symmetric tuning system, all the notes on one side of the bridge correspond to the lines of the musical staff and all the notes on the other side correspond to the staff spaces. So, whatever key the music is written in, determine where the root note is of the scale. The method is then to mentally let this be the position of the instruments root note "G" for example. If the written note is on a staff line, let that staff line represent the "G" string on the gravikord and all the other strings on that side of the bridge will correspond spatially and sequentially to the other staff lines, all the notes on the opposite side of the bridge will correspond spatially and sequentially to the staff spaces. If the written musical root lies in a space then the opposite is true. Now the staff itself accurately represents spatially the strings and the notes on the gravikord and one can read the music as if it were written in a tablature designed for the gravikord. The position of the written notes on the staff directly indicate which string to play on the instrument.

.tiff.jpg)

Gravi-kora

Music for gravi-kora can be written in the normal grand staff method using the G clef and F clef.

However, gravi-kora scores can also be written on a single G clef, following the Keur Moussa system. This notation system was created for the kora by Brother Dominique Catta, a monk of the Keur Moussa Monastery (Senegal). The seven low notes that should be written on the F clef are replaced by Arabic or Roman numerals and written on the G clef. More than 200 scores already written for kora solo or kora and Western instruments can therefore be played on the gravi-kora.

Performers

Gravikord

Bob (Robert) Grawi has recorded several CDs, as a solo player and with the Gravikord Duo and the Gravikord Ensemble (The Gravikord Duo consists of Bob Grawi, gravikord and percussion, and Pip Klein, flute; The Gravikord Ensemble adds David Dachinger, bassoon): Making Waves, 1988, Take That Music; Rising Tide, 1991, Take That Music; Cherries & Stars, 1996, Take That Music. Peter Pringle of Canada has recorded an improvisation for gravikord & theremin.[6] Ziko Hart of Australia has recorded original solo music on the gravikord. The jazz guitarist Kazumi Watanabe of Japan has produced a broadcast Japanese TV video and is also a gravikord owner.

Gravi-kora

Foday Musa Suso featured an early version of the gravi-kora in recordings with Herbie Hancock,[7] and on Suso's CD New World Power.[8] The Gravi-kora was adopted by Daniel Berkman of San Francisco [9] and Jacques Burtin of Spain [10] who are well known musicians and who have also produced their own original recordings with the instrument.

Discography

- 1988 - Making Waves - Bob Grawi (Take That Music)

- 1990 - New World Power - Foday Musa Suso (Island Records)

- 1991 - Rising Tide - Bob Grawi (Take That Music)

- 1996 - Cherries & Stars - Bob Grawi (Take That Music)

- 1998 - Gravikords, Whirlies & Pyrophones - Bob Grawi and Multiple Artists (Ellipsis Arts)

- 2005 - Calabashmoon - Daniel Berkman (Magnatune)

- 2008 - Le Chant de la Foret - Jacques Burtin (Bayard Musique)

- 2009 - Heartstrings - Daniel Berkman (Magnatune)

- 2015 - Headlands - Daniel Berkman

- 2015 - From The Heart - Ziko Hart (Mad CDs)

Published articles

The Gravikord has received its own entry describing the instrument in detail in the latest published edition of the multi-volume "Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments" Second Edition, edited by Laurence Libin, on page 469.

Other articles describing or referencing the gravikord have appeared in the following publications: Curio Magazine,[11] Daily News,[12] Dirty Linen,[13] Experimental Musical Instruments,[1] Folk Harp Journal,[14] Gravikords Whirlies & Pyrophones,[2] Guitar Player Magazine,[4] Metropolitan Museum of Art,[15] New Sounds,[16] Science News,[17] Smithsonian Magazine,[18] The New York Times,[3][19] The Washington Post,[20] Vanity Fair,[5] among others.

See also

References

- 1 2 Experimental Musical Instruments, April 1988, Volume III, Number 6, pgs 4-7.

- 1 2 Gravikords Whirlies & Pyrophones, Bart Hopkin, CD/Book, Ellipsis Arts, 1996, pgs 82-83 (see: AllMusic review).

- 1 2 The New York Times, Sunday December 15, 1996, Pg h45.

- 1 2 Guitar Player, February 1988, pg 12.

- 1 2 Vanity Fair, November 2000, pg 176.

- ↑ Peter Pringle's Afrique Improvisation for Gravikord and Theremin, Synthtopia 2010. Video: .

- ↑ Village Life, Columbia, 1985 ; Jazz Africa, Polydor, 1987.

- ↑ New World Power, produced by Bill Laswell and Foday Musa Suso, Island Records, 1990.

- ↑ Calabash Moon, Magnatune, 2005 ; Heartstrings, Magnatune, 2009. Video (Daniel Berkman on Gravikord, 1998).

- ↑ Le Chant de la Forêt, Bayard Musique, 2008. Video (Gravi-kora improvisation by Jacques Burtin, 2010).

- ↑ Curio, Spring 1997, pg 64.

- ↑ Daily News, Sunday, April 17, 1988.

- ↑ Dirty Linen, Issue 44, February/March 1993.

- ↑ Folk Harp Journal, Spring 1995, Number 87, pgs 37-38.

- ↑ Metropolitan Museum of Art, Enduring Rhythms: African Musical Instruments in the Americas October 1996 through August 1997.

- ↑ New Sounds – A Listner's Guide to New Music, John Schaefer, Harper Collins, April 1987.

- ↑ Science News, Volume 129, No. 8, February 22, 1986.

- ↑ Smithsonian, April 1999, Pgs 108-109.

- ↑ The New York Times, by Jon Pareles, Friday, January 9, 1998.

- ↑ The Washington Post, Sunday, February 16, 1986.