Gravitational constant

The gravitational constant (also known as "universal gravitational constant", or as "Newton's constant"), denoted by the letter G, is an empirical physical constant involved in the calculation of gravitational effects in Sir Isaac Newton's law of universal gravitation and in Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity. Its value is approximately 6.674×10−11 N⋅m2/kg2.[1]

Law of gravitation

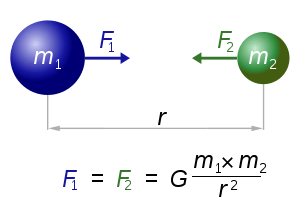

According to Newton's law of universal gravitation, the attractive force (F) between two bodies is directly proportional to the product of their masses (m1 and m2), and inversely proportional to the square of the distance, r, (inverse-square law) between them:

- .

The constant of proportionality, G, is the gravitational constant. Colloquially, the gravitational constant is also called "Big G", for disambiguation with "small g" (g), which is the local gravitational field of Earth (equivalent to the free-fall acceleration).[2] The two quantities are related by (where is the mass of the Earth and is the Earth radius).

In the general theory of relativity, the Einstein field equations,[3][4]

- ,

Newton's constant appears in the proportionality between spacetime curvature and energy. The scaled gravitational constant (depending on the choice of definition of the stress-energy tensor also normalized as ) is also known as Einstein's constant.[5]

Value and dimensions

The gravitational constant is a physical constant that is difficult to measure with high accuracy.[6] This is because the gravitational force is extremely weak compared with other fundamental forces.[7]

In SI units, the 2014 CODATA-recommended value of the gravitational constant (with standard uncertainty in parentheses) is:[1][8]

This corresponds to a relative standard uncertainty of 4.7×10−5.

The dimensions assigned to the gravitational constant are force times length squared divided by mass squared; this is equivalent to length cubed, divided by mass and by time squared:

In SI base units, this amounts to meters cubed per kilogram per second squared:

- .

In cgs, G can be written as:

Natural units

The gravitational constant is taken as the basis of the Planck units: it is equal to the cube of the Planck length divided by the product of the Planck mass and the square of Planck time:

In other words, in Planck units, G has the numerical value of 1.

Thus, in Planck units, and other natural units taking G as their basis, the gravitational constant cannot be measured as it is set to its value by definition. Depending on the choice of units, variation in a physical constant in one system of units shows up as variation of another constant in another system of units; only variation in dimensionless physical constants is preserved independently of the choice of units; in the case of the gravitational constant, such a dimensionless value is the gravitational coupling constant,

- ,

a measure for the gravitational attraction between a pair of electrons, proportional to the square of the electron rest mass.

Orbital mechanics

In astrophysics, it is convenient to measure distances in parsecs (pc), velocities in kilometers per second (km/s) and masses in solar units M⊙. In these units, the gravitational constant is:

In orbital mechanics, the period P of an object in circular orbit around a spherical object obeys

where V is the volume inside the radius of the orbit. It follows that

This way of expressing G shows the relationship between the average density of a planet and the period of a satellite orbiting just above its surface.

For elliptical orbits, applying Kepler's 3rd law, expressed in units characteristic of Earth's orbit:

- ,

where distance is measured in astronomical units (AU), time in years, and mass in solar masses (M⊙).

History of measurement

The gravitational constant appears in Newton's law of universal gravitation, but it was not measured until seventy-one years after Newton's death by Henry Cavendish with his Cavendish experiment, performed in 1798 (Philosophical Transactions 1798). Cavendish measured G implicitly, using a torsion balance invented by the geologist Rev. John Michell. He used a horizontal torsion beam with lead balls whose inertia (in relation to the torsion constant) he could tell by timing the beam's oscillation. Their faint attraction to other balls placed alongside the beam was detectable by the deflection it caused. Cavendish's aim was not actually to measure the gravitational constant, but rather to measure Earth's density relative to water, through the precise knowledge of the gravitational interaction. In modern units, the density that Cavendish calculated implied a value for G of 6.754×10−11 m3 kg−1 s−2.[9]

The accuracy of the measured value of G has increased only modestly since the original Cavendish experiment. G is quite difficult to measure, because gravity is much weaker than other fundamental forces, and an experimental apparatus cannot be separated from the gravitational influence of other bodies. Furthermore, gravity has no established relation to other fundamental forces, so it does not appear possible to calculate it indirectly from other constants that can be measured more accurately, as is done in some other areas of physics. Published values of G have varied rather broadly, and some recent measurements of high precision are, in fact, mutually exclusive.[6][10] This led to the 2010 CODATA value by NIST having 20% increased uncertainty than in 2006.[11] For the 2014 update, CODATA reduced the uncertainty to less than half the 2010 value.

In the January 2007 issue of Science, Fixler et al. described a new measurement of the gravitational constant by atom interferometry, reporting a value of G = 6.693(34)×10−11 m3 kg−1 s−2.[12] An improved cold atom measurement by Rosi et al. was published in 2014 of G = 6.67191(99)×10−11 m3 kg−1 s−2.[13]

A controversial 2015 study of some previous measurements of G, by Anderson et al., suggested that most of the mutually exclusive values can be explained by a periodic variation.[14] The variation was measured as having a period of 5.9 years, similar to that observed in length of day (LOD) measurements, hinting at a common physical cause which is not necessarily a variation in G. A response was produced by some of the original authors of the G measurements used in Anderson et al.[15] This response notes that Anderson et al. not only omitted measurements, they also used the time of publication not the time the experiments were performed. A plot with estimated time of measurement from contacting original authors seriously degrades the length of day correlation. Also taking the data collected over a decade by Karagioz and Izmailov shows no correlation with length of day measurements.[15][16] As such the variations in G most likely arise from systematic measurement errors which have not properly been accounted for.

Under the assumption that the physics of type Ia supernovae are universal, analysis of observations of 580 type Ia supernovae has shown that the gravitational constant has varied by less than one part in ten billion per year over the last nine billion years.[17]

The GM product

The quantity GM—the product of the gravitational constant and the mass of a given astronomical body such as the Sun or Earth—is known as the standard gravitational parameter and is denoted μ. Depending on the body concerned, it may also be called the geocentric or heliocentric gravitational constant, among other names.

This quantity gives a convenient simplification of various gravity-related formulas. Also, for celestial bodies such as Earth and the Sun, the value of the product GM is known much more accurately than each factor independently. Indeed, the limited accuracy available for G limits the accuracy of determination of such masses in the first place.

For Earth, using M⊕ as the symbol for the mass of Earth, we have

For Sun, we have

Calculations in celestial mechanics can also be carried out using the unit of solar mass rather than the standard SI unit kilogram. In this case we use the Gaussian gravitational constant k, where

and

- A is the astronomical unit;

- D is the mean solar day;

- S is the solar mass.

If instead of mean solar day we use the sidereal year as our time unit, the value of ks is very close to 2π (k = 6.28315).

The standard gravitational parameter GM appears as above in Newton's law of universal gravitation, as well as in formulas for the deflection of light caused by gravitational lensing, in Kepler's laws of planetary motion, and in the formula for escape velocity.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Mohr, Peter J.; Newell, David B.; Taylor, Barry N. (2015-07-21). "CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants: 2014". arXiv:1507.07956

[physics.atom-ph].

[physics.atom-ph]. - ↑ Gundlach, Jens H.; Merkowitz, Stephen M. (2002-12-23). "University of Washington Big G Measurement". Astrophysics Science Division. Goddard Space Flight Center.

Since Cavendish first measured Newton's Gravitational constant 200 years ago, "Big G" remains one of the most elusive constants in physics

. Fundamentals of Physics 8th ed., Halliday/Resnick/Walker, ISBN 978-0-470-04618-0 p. 336. - ↑ Grøn, Øyvind; Hervik, Sigbjorn (2007). Einstein's General Theory of Relativity: With Modern Applications in Cosmology (illustrated ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-387-69200-5. Extract of page 180

- ↑ Einstein, Albert (1916). "The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity". Annalen der Physik. 354 (7): 769. Bibcode:1916AnP...354..769E. doi:10.1002/andp.19163540702. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-06.

- ↑ Ronald Adler; Maurice Bazin; Menahem Schiffer (1975). Introduction to General Relativity (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-000423-4. p. 345.

- 1 2 George T. Gillies (1997), "The Newtonian gravitational constant: recent measurements and related studies", Reports on Progress in Physics, 60 (2): 151–225, Bibcode:1997RPPh...60..151G, doi:10.1088/0034-4885/60/2/001. A lengthy, detailed review. See Figure 1 and Table 2 in particular.

- ↑ For example, the gravitational force between an electron and proton one meter apart is approximately 10−67 N, whereas the electromagnetic force between the same two particles is approximately 10−28 N. The electromagnetic force in this example is some 39 orders of magnitude (i.e. 1039) greater than the force of gravity—roughly the same ratio as the mass of the Sun to a microgram.

- ↑ "Newtonian constant of gravitation G". CODATA, NIST.

- ↑ Brush, Stephen G.; Holton, Gerald James (2001), Physics, the human adventure: from Copernicus to Einstein and beyond, New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, p. 137, ISBN 0-8135-2908-5

- ↑ Peter J. Mohr; Barry N. Taylor (January 2005), "CODATA recommended values of the fundamental physical constants: 2002" (PDF), Reviews of Modern Physics, 77 (1): 1–107, Bibcode:2005RvMP...77....1M, doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.77.1, retrieved 2006-07-01. Section Q (pp. 42–47) describes the mutually inconsistent measurement experiments from which the CODATA value for G was derived.

- ↑ "CODATA recommended values of the fundamental physical constants: 2010" (PDF). Rev Mod Phys. 84: 1527–1605. 13 November 2012. arXiv:1203.5425

. Bibcode:2012RvMP...84.1527M. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.84.1527.

. Bibcode:2012RvMP...84.1527M. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.84.1527. - ↑ J. B. Fixler; G. T. Foster; J. M. McGuirk; M. A. Kasevich (2007-01-05), "Atom Interferometer Measurement of the Newtonian Constant of Gravity", Science, 315 (5808): 74–77, Bibcode:2007Sci...315...74F, doi:10.1126/science.1135459, PMID 17204644

- ↑ Schlamminger, Stephan (18 June 2014). "Fundamental constants: A cool way to measure big G". Nature. 510: 478–480. Bibcode:2014Natur.510..478S. doi:10.1038/nature13507.

- ↑ J.D. Anderson; G. Schubert; V. Trimble; M.R. Feldman (April 2015), "Measurements of Newton's gravitational constant and the length of day" (PDF), EPL, 110: 10002, arXiv:1504.06604

, Bibcode:2015EL....11010002A, doi:10.1209/0295-5075/110/10002

, Bibcode:2015EL....11010002A, doi:10.1209/0295-5075/110/10002 - 1 2 Schlamminger, S.; Gundlach, J. H.; Newman, R. D. (2015). "Recent measurements of the gravitational constant as a function of time". Physical Review D. 91 (12). arXiv:1505.01774

. Bibcode:2015PhRvD..91l1101S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.91.121101. ISSN 1550-7998.

. Bibcode:2015PhRvD..91l1101S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.91.121101. ISSN 1550-7998. - ↑ Karagioz, O. V.; Izmailov, V. P. (1996). "Measurement of the gravitational constant with a torsion balance". Measurement Techniques. 39 (10): 979–987. doi:10.1007/BF02377461. ISSN 0543-1972.

- ↑ J. Mould; S. A. Uddin (2014-04-10), "Constraining a Possible Variation of G with Type Ia Supernovae", Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia, 31: e015, arXiv:1402.1534

, Bibcode:2014PASA...31...15M, doi:10.1017/pasa.2014.9

, Bibcode:2014PASA...31...15M, doi:10.1017/pasa.2014.9 - ↑ Ries, J.C.; Eanes, R.J.; Shum, C.K.; Watkins, M.M. (20 March 1992). "Progress in the determination of the gravitational coefficient of the Earth". Geophysical Research Letters. 19 (6): 529–531. Bibcode:1992GeoRL..19..529R. doi:10.1029/92GL00259. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

References

- E. Myles Standish. "Report of the IAU WGAS Sub-group on Numerical Standards". In Highlights of Astronomy, I. Appenzeller, ed. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1995. (Complete report available online: PostScript; PDF. Tables from the report also available: Astrodynamic Constants and Parameters)

- Jens H. Gundlach; Stephen M. Merkowitz (2000), "Measurement of Newton's Constant Using a Torsion Balance with Angular Acceleration Feedback", Physical Review Letters, 85 (14): 2869–2872, arXiv:gr-qc/0006043

, Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.2869G, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.2869, PMID 11005956

, Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.2869G, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.2869, PMID 11005956

External links

- Newtonian constant of gravitation G at the National Institute of Standards and Technology References on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty

- The Controversy over Newton's Gravitational Constant — additional commentary on measurement problems