Ground loop (electricity)

In an electrical system, a ground loop or earth loop is an equipment and wiring configuration in which there are multiple paths for electricity to flow to ground. The multiple paths form a loop which can pick up stray current through electromagnetic induction which results in unwanted current in a conductor connecting two points that are supposed to be at the same electric potential, often, but are actually at different potentials.

Ground loops are a major cause of noise, hum, and interference in audio, video, and computer systems. They do not in themselves create an electric shock hazard; however, the inappropriate connections that cause a ground loop often result in poor electrical bonding, which is explicitly required by safety regulations in certain circumstances. In any case the voltage difference between the ground terminals of each item of equipment is small. A severe risk of electric shock occurs when equipment grounds are improperly removed in an attempt to cure the problems thought to be caused by ground loops.

|

Ground loop 50 Hz sound

Ground loop at 50 Hz captured with audio equipment. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Description

A ground loop is the result of careless or inappropriate design or interconnection of electrical equipment that results in there being multiple paths to ground where this is not required, so a complete loop is formed. In the simplest case, two items of equipment, A and B, both intended to be grounded for safety reasons, are each connected to a power source (wall socket etc) by a 3 conductor cable and plug, containing a protective ground conductor, usually green/yellow, in accordance with normal safety regulations and practice. This only becomes a problem when one or more signal cables are then connected between A and B, to pass data or audio signals from one to the other. The shield (screen) of the data cable is typically connected to the grounded equipment chassis of both A and B. There is now a ground loop.

The ground loop will be carrying some current at the local supply frequency, typically 50 Hz or 60 Hz, due to electromagnetic induction from current-carrying conductors nearby. There is an AC magnetic field everywhere in developed areas; however, its magnitude and direction depend strongly on the local environment and arrangement of current-carrying wiring. This influences the current induced in the ground loop, which is also dependent on the area enclosed by the ground loop and its orientation. The impedance of the loop, basically just its resistance at low frequencies, also influences the induced current that will flow. It is important to realise that for a ground loop to cause problems, there must be a local magnetic field produced by power frequency or other systems. It is the combination of radiated field and receptive ground loop that causes problems, and the situation can be improved by attention to either one, or both of these. In effect, the ground loop is the secondary of a very loosely coupled transformer, the primary being the summation of all current carrying conductors nearby. Transformer action limits the induced voltage in the loop, and the weak coupling limits the maximum current that will flow, even if the loop resistance is very low. The maximum induced energy is normally quite small, and except in situations very close to a radiating loop carrying high current, there is no prospect of inducing sufficient energy to cause a hazard to humans.

Some places where high fields may exist, with the potential for hazards to arise in a ground loop close by, are close to AC electrified railways with simple return through the rails, where the overhead wiring may be carrying several hundred amps at 50 or 60 Hz (the voltage is not important), or close to a power distribution network carrying high currents with widely spaced wires. Again, the voltage is not relevant. Inside a building, the wiring may include radiating loops, e.g. careless layout may result in the live feed to a lighting circuit, via the switch, take a different route than the neutral (return) conductor, creating a radiating loop, but this will not be able to couple sufficient energy to create a hazard.

It has been alleged that a significant cause of current in the ground loop is voltage drop along the equipment protective ground conductors. This is rarely significant, because safety regulations place strict limits on ground leakage current, and ground conductor impedance. For modest sized pieces of equipment such as most audio equipment the ground leakage will be typically less than 2 mA, and the protective ground impedance less than 1 ohm, so this effect will only cause a few milliamps of current to flow in the loop. The current arising due to magnetic induction is liable to be at least one or two orders of magnitude greater.

If A and B are simple electrical apparatus, the signals between them being of a simple nature, such as 24V DC to control relays, this ground loop is harmless and merely reinforces the grounding system, such that, if for example, B develops a fault causing its metalwork to become live, in addition to its own protective ground conductor there is an additional path to ground via A, so the momentary rise in potential before the fuse or circuit breaker operates to remove power will be reduced somewhat, improving safety.

However, if A and B are electronic apparatus such as parts of an audio system, or a computer system, the signal(s), typically in the region of millivolts to a few volts, passing between them will be vulnerable to corruption.

Ground loops in low frequency audio and instrumentation systems

If, for example, a domestic HiFi system has a grounded turntable and a grounded preamplifier connected by a thin screened cable (or cables, in a stereo system) using phono connectors, the cross-section of copper in the cable screen(s) is likely to be less than that of the protective ground conductors for the turntable and the preamplifier. So, when a current is induced in the loop, there will be a voltage drop along the signal ground return. This is directly additive to the wanted signal, and will result in objectionable hum. For instance, if a current i of 1mA at the local power frequency is induced in the ground loop, and the resistance R of the screen of the signal cable is 100 milliohms, the voltage drop will be = 100 microvolts. This is a significant fraction of the output voltage of a moving coil pickup cartridge, and a truly objectionable hum will result.

In practice this case usually does not happen because the pickup cartridge, an inductive voltage source, need have no connection to the turntable metalwork, and so the signal ground is isolated from the chassis or protective ground at that end of the link. Therefore there is no current loop, and no hum problem due directly to the grounding arrangements.

In a more complex situation, such as sound reinforcement systems, public address systems, music instrument amplifiers, recording studio and broadcast studio equipment , there are many signal sources in items of AC powered equipment, feeding many inputs on other items of equipment. Careless interconnection is virtually guaranteed to result in hum problems. Ignorant or inexperienced people have on many occasions attempted to cure these problems by removing the protective ground conductor on some items of equipment, to disrupt ground loops. This has resulted in many fatal accidents, when some item of equipment has an insulation failure, the only path to ground is via an audio interconnection, and someone unplugs this, exposing themselves to anything up to the full supply voltage. The practice of "lifting" protective grounds is rightly illegal in countries which have proper electrical safety regulations, and in some cases can result in criminal prosecution.

Therefore solving "hum" problems must be done in the signal interconnections, and this is done in two main ways, which may be combined.

- Isolation

Isolation is the quickest, quietest and most foolproof method of solving "hum" problems. The signal is isolated by a small transformer, such that the source and destination equipment each retain their own protective ground connections, but there is no through connection from one to the other in the signal path. By transformer isolating all unbalanced connections, we can connect unbalanced connections with balanced connections and thus fixing the "hum" problem. In analog applications such as audio the physical limitations of the transformers cause some signal degradation, by limiting the bandwidth and adding some distortion.

- Balanced interconnection

This turns the spurious noise due to ground loop current into Common-mode interference while the signal is differential, enabling them to be separated at destination, by circuits having a high common-mode rejection ratio. Each signal output has a counterpart in anti-phase, so there are two signal lines, often called hot and cold, carrying equal and opposite voltages, and each input is differential, responding to the difference in potential between the hot and cold wires, not their individual voltages with respect to ground. There are special semiconductor output drivers and line receivers to enable this system to be implemented with a small number of components. These generally give better overall performance than transformers, and probably cost less, but are still relatively expensive because the silicon "chips" necessarily contain a number of very precisely matched resistors. This level of matching, to obtain high common mode rejection ratio, is not realistically obtainable with discrete component designs.

With the increasing trend towards digital processing and transmission of audio signals, the full range of isolation by small pulse transformers, optocouplers or fibre optics become more useful. Standard protocols such as S/PDIF, AES3 or TOSLINK are available in relatively inexpensive equipment and allow full isolation, so ground loops need not arise, especially when connecting between audio systems and computers.

In instrumentation systems, the use of differential inputs with high common mode rejection ratio, to minimise the effects of induced AC signals on the parameter to be measured, is widespread. It may also be possible to introduce narrow notch filters at the power frequency and its lower harmonics; however, this can not be done in audio systems due to the objectionable audible effects on the wanted signal.

Ground loops in analog video systems

In analog video, mains hum can be seen as hum bars (bands of slightly different brightness) scrolling vertically up the screen. These are frequently seen with video projectors where the display device has its case grounded via a 3-prong plug, and the other components have a floating ground connected to the CATV coax. In this situation the video cable is grounded at the projector end to the home electrical system, and at the other end to the cable TV's ground, inducing a current through the cable which distorts the picture. This problem can not be solved by a simple isolating transformer in the video feed, as the video signal has a net DC component, which varies. The isolation must be put in the CATV RF feed instead. The internal design of the CATV box should have provided for this.

Ground loop issues with television coaxial cable can affect any connected audio devices such as a receiver. Even if all of the audio and video equipment in, for example, a home theatre system is plugged into the same power outlet, and thus all share the same ground, the coaxial cable entering the TV is sometimes grounded by the cable company to a different point than that of the house's electrical ground creating a ground loop, and causing undesirable mains hum in the system's speakers. Again, this problem is due entirely to incorrect design of the equipment.

Ground loops in digital and RF systems

In digital systems, which commonly transmit data serially (RS232, RS485, USB, Firewire, DVI, HDMI etc) the signal voltage is often much larger than induced power frequency AC on the connecting cable screens, but different problems arise. Of those protocols listed, only RS232 is single-ended with ground return, but it is a large signal, typically + and - 12V, all the others being differential. Simplistically, the big problem with the differential protocols is that with slightly mismatched capacitance from the hot and cold wires to ground, or slightly mismatched hot and cold voltage swings or edge timing, the currents in the hot and cold wires will be unequal, and also a voltage will be coupled onto the signal screen, which will cause a circulating current at signal frequency and its harmonics, extending up to possibly many GHz. The difference in signal current magnitudes between the hot and cold conductors will try to flow from, for example, item A's protective ground conductor back to a common ground in the building, and back along item B's protective ground conductor. This may involve a large loop area and cause significant radiation, violating EMC regulations and causing interference to other equipment.

As a result of the Reciprocity Theorem the same loop will act as a receiver of high frequency noise and this will be coupled back into the signal circuits, with the potential to cause serious signal corruption and data loss. On a video link, for example, this may cause visible noise on the display device or complete non-operation. In a data application. such as between a computer and its network storage, this may cause very serious data loss.

The "cure" for these problems is different to that for low frequency and audio ground loop problems. For example, in the case of Ethernet 10BASE-T, 100BASE-TX and 1000BASE-T, where the data streams are Manchester encoded to avoid any DC content, the ground loop(s) which would occur in most installations are avoided by using signal isolating transformers, often incorporated into the body of the fixed RJ45 jack.

Many of the other protocols break the ground loop at data baud rate frequency by fitting small ferrite cores around the connecting cables near each end, and/or just inside the equipment boundary. These form a common-mode choke which inhibit unbalanced current flow, without affecting the differential signal. This technique is equally valid for coaxial interconnects, and many camcorders have ferrite cores fitted to some of their auxiliary cables such as DC charging and external audio input, to break the high frequency current flow if the user inadvertently creates a ground loop when connecting external equipment.

RF cabling, usually coaxial, is also often equipped with a ferrite core, often a fairly large toroid, through which the cable can be wound perhaps 10 times to add a useful amount of common mode inductance.

Where no power need be transmitted, only digital data, the use of fiber optics can remove many ground loop problems, and sometimes safety problems too, but there are practical limitations. However, optical isolators or optocouplers are frequently used to provide ground loop isolation, and often safety isolation and the prevention of fault propagation.

Internal ground loops in equipment

Typically these are caused by incompetent design. Where there is mixed signal technology on a printed circuit board, e.g. analogue, digital and possibly RF, it is usually necessary for a highly skilled engineer to specify the layout of where the grounds are to be interconnected. Typically the digital section will have its own ground plane to obtain the necessary low inductance grounding and avoid ground bounce which can cause severe digital malfunction. But digital ground current must not pass through the analog grounding system, where voltage drop due to the finite ground impedance would cause noise to be injected into the analogue circuits. Phase lock loop circuits are particularly vulnerable because the VCO loop filter circuit is working with sub-microvolt signals when the loop is locked, and any disturbance will cause frequency jitter and possible loss of lock.

Generally the analog and digital parts of the circuit are in separate areas of the PCB, with their own ground planes, and these are tied together at a carefully chosen star point. Where analog to digital converters (ADCs) are in use, the star point may have to be at or very close to the ground terminals of the ADC(s).

Differential signal transmission, optical or transformer isolation, or fibre optic links, are also used in PCBs in extreme cases.

Mitigating the effects of ground loops in audio systems

- Supply the entire system from one wall socket, if its power rating is sufficient. Distribute the power to various bits of equipment in a tree structure. Commonly there will be "front" equipment such as powered foldback speakers on stage and "back" equipment such as the mixing desk and effects rack, connected by an audio multicore cable or snake. Route the power cable to the "front" area close to the snake, to minimise loop area. It will not couple noise into the snake directly, as the snake will contain screened balanced pairs.

- Make sure that every signal path is truly balanced. Not possible with "insert" connections between mixer and effects rack, which are invariably single ended, so keep the cables short and think about reinforcing the ground path between equipments by connecting a heavy copper braid between effects rack and mixer.

- Ensure that there are no spurious ground loops, possibly intermittent, on microphone cables. Usually this means ensuring that the shell of XLR connectors is isolated from pin 1 (screen ground), in case they touch other similar cables or spurious grounds, but a better way is fitting an overall insulating sleeve over the connector body, if this can be done without obstructing the unlocking button.

- If absolutely necessary, insert isolating transformers in problematic signal lines.

- Research other options on the web, but on no account even think about lifting any protective grounds.

History

The causes of ground loops have been thoroughly understood for more than half a century, and yet they are still a very common problem where multiple components are interconnected with cables. The underlying reason for this is an unavoidable conflict between the two different functions of a grounding system: reducing electronic noise and preventing electric shock. From a noise perspective it is preferable to have "single-point grounding", with the system connected to the building ground wire at only one point. National electrical codes, however, often require all AC-powered components to have third-wire grounds; from a safety standpoint it is preferable to have each AC component grounded. However, the multiple ground connections cause ground loops when the components are interconnected by signal cables, as shown below.

How it works

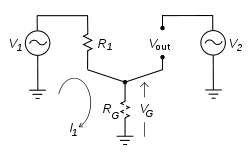

The circuit diagram, right, illustrates a simple ground loop. Two circuits share a common wire connecting them to ground, which has a resistance of . Ideally, the ground conductor would have no resistance (), so the voltage drop across it, , should be zero, keeping the point at which the circuits connect at a constant ground potential, isolating them from each other. In that case, the output of circuit 2 is simply .

However, if , it and will together form a voltage divider. As a result, if a current, , is flowing through from circuit 1, a voltage drop , across will occur and the ground connection of both circuits will no longer be at the actual ground potential. This voltage across the ground conductor will be applied to circuit 2 and added to the output:

Thus the two circuits are no longer isolated from each other and circuit 1 can introduce interference into the output of circuit 2. If circuit 2 is an audio system and circuit 1 has large AC currents flowing in it, the interference may be heard as a 50 or 60 Hz hum in the speakers. Also, both circuits will have voltage on their grounded parts that may be exposed to contact, possibly presenting a shock hazard. This is true even if circuit 2 is turned off.

Although they occur most often in the ground conductors of electrical equipment, ground loops can occur wherever two or more circuits share a common conductor or current path, if enough current is flowing to cause a significant voltage drop along the conductor.

Common ground loops

A common type of ground loop is due to faulty interconnections between electronic components, such as laboratory or recording studio equipment, or home component audio, video, and computer systems. This creates inadvertent closed loops in the ground wiring circuit, which can allow stray 50/60 Hz AC current to flow through the ground conductors of signal cables.[1][2][3][4] The voltage drops in the ground system caused by these currents are added to the signal path, introducing noise and hum into the output. The loops can include the building's utility wiring ground system when more than one component is grounded through the "third wire" in their power cords.

Ground currents on signal cables

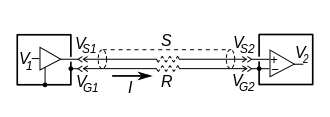

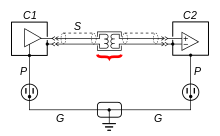

Fig. 1 shows a signal cable S linking two electronic components, including the typical line driver and receiver amplifiers (triangles).[3] The cable has a ground or shield conductor which is connected to the chassis ground of each component. The driver amplifier in component 1 (left) applies signal V1 between the signal and ground conductors of the cable. At the destination end (right), the signal and ground conductors are connected to a differential amplifier. This produces the signal input to component 2 by subtracting the shield voltage from the signal voltage to eliminate common-mode noise picked up by the cable

If a current I (return signal current + ground loop current due to established ground loop by connection of grounded chassis of both components with cable shield) is flowing through the ground conductor, the resistance R of the conductor will create a voltage drop along the cable ground of IR, so the destination end of the ground conductor will be at a different potential than the source end

Since the differential amplifier has high impedance, little current flows in the signal wire, therefore there is no voltage drop across it: The ground voltage appears to be in series with the signal voltage V1 and adds to it

If I is an AC current this can result in noise added to the signal path in component 2. In effect the ground current "tricks" the component into thinking it is in the signal path.

Sources of ground current

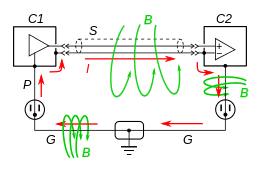

The diagrams at right show a typical ground loop caused by a signal cable S connecting two grounded electronic components C1 and C2. The loop consists of the signal cable's ground conductor, which is connected through the components' metal chassis to the ground wires P in their "three wire" power cords, which are plugged into outlet grounds which are connected through the building's utility ground wire system G.

Such loops in the ground path can cause currents in signal cable grounds by two main mechanisms:

- Ground loop currents can be induced by stray AC magnetic fields[3][5] (B, green) The ground loop constitutes a conductive wire loop which may have a large area of several square meters. It acts like a short circuited single-turn "transformer winding"; any AC magnetic flux passing through the loop, from nearby transformers, electric motors, or just adjacent power wiring, will induce currents in the loop by induction. Since its resistance is very low, often less than 1 ohm, the induced currents can be large.

- Another source of ground loop currents is current leaking from the "hot" side of the power line into the ground system.[1][6] In addition to resistive leakage, current can also be induced through low impedance capacitive or inductive coupling. The ground potential at different outlets may differ by as much as 10 to 20 volts[2] due to voltage drops from these currents. Fig. 2 shows leakage current from an appliance such as an electric motor A flowing through the building's ground system G to the neutral wire at the utility ground bonding point at the service panel. The ground loop between components C1 and C2 creates a second parallel path for the current.[6] The current divides, with some passing through component C1, the signal cable S ground conductor, C2 and back through the outlet into the ground system G. The AC voltage drop across the cable's ground conductor from this current introduces hum or interference into component C2.[6]

Solutions

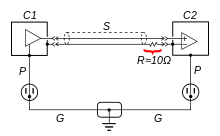

The solution to ground loop noise is to break the ground loop, or otherwise prevent the current from flowing. The diagrams show several solutions which have been used

- Group the cables involved in the ground loop into a bundle or "snake".[1] The ground loop still exists, but the two sides of the loop are close together, so stray magnetic fields induce equal currents in both sides, which cancel out.

- Create a break in the signal cable shield conductor.[3] (but signal still can find return path from C2 chassis through G to C1. However, as there is no return current on cable shield, characteristic impedance of cable can be changed) The break should be at the load end. This is often called "ground lifting". It is the simplest solution; it leaves the ground currents to flow through the other arm of the loop. Some modern components have "ground lifting switches" at inputs, which disconnect the ground. One problem with this solution is if the other ground path to the component is removed, it will leave the component ungrounded, "floating". Stray leakage currents will cause a very loud hum in the output, possibly damaging speakers.

- Put a small resistor of about 10Ω in the cable shield conductor, at the load end.[3] This is large enough to reduce magnetic field induced currents, but small enough to keep the component grounded if the other ground path is removed, preventing the loud hum mentioned above.

- Use a ground loop isolation transformer in the cable.[2][3] This is considered the best solution, as it breaks the DC connection between components while passing the differential signal on the line. Even if one or both components are ungrounded (floating), no noise will be introduced. The better isolation transformers have grounded shields between the two sets of windings. Optoisolators can perform the same task for digital lines.

- In circuits producing high frequency noise such as computer components, ferrite bead chokes are placed around cables just before the termination to the next appliance (e.g., the computer). These present a high impedance only at high frequency, so they will effectively stop radio frequency and digital noise, but will have little effect on 50/60 Hz noise.

- A technique used in recording studios is to interconnect all the metal chassis with heavy conductors like copper strip, then connect to the building ground wire system at one point; this is referred to as "single-point grounding". However, many components are grounded through their 3-wire power cords, resulting in multipoint grounds.

A hazardous technique used by less knowledgeable people is to break the "third wire" ground conductor P in one of the component's power cords, by removing the ground pin on the plug, or using a "cheater" ground adapter. This should NEVER be done, as it can create an electric shock hazard by leaving one of the components ungrounded.[2][3]

Balanced lines

A more comprehensive solution is to use equipment that employs balanced signal lines. Ground noise can only get into the signal path in an unbalanced line, in which the ground or shield conductor serves as one side of the signal path. In a balanced cable, the signal is sent as a differential signal along a pair of wires, neither of which are connected to ground. Any noise from the ground system induced in the signal lines is a common-mode signal, identical in both wires. Since the line receiver at the destination end only responds to differential signals, a difference in voltage between the two lines, the common-mode noise is cancelled out. Thus these systems are very immune to electrical noise, including ground noise. Professional and scientific equipment often uses balanced cabling.

In circuit design

Ground and ground loops are also important in circuit design. In many circuits, large currents may exist through the ground plane, leading to voltage differences of the ground reference in different parts of the circuit, leading to hum and other problems. Several techniques should be used to avoid ground loops, and otherwise, guarantee good grounding:

- The external shield, and the shields of all connectors, should be connected.

- If the power supply design is non-isolated, this external chassis ground should be connected to the ground plane of the PCB at only one point; this avoids large current through the ground plane of the PCB.

- If the design is an isolated power supply, this external ground should be connected to the ground plane of the PCB via a high voltage capacitor, such as 2200 pF at 2 kV.

- If the connectors are mounted on the PCB, the outer perimeter of the PCB should contain a strip of copper connecting to the shields of the connectors. There should be a break in copper between this strip, and the main ground plane of the circuit. The two should be connected at only one point. This way, if there is a large current between connector shields, it will not pass through the ground plane of the circuit.

- A star topology should be used for ground distribution, avoiding loops.

- High-power devices should be placed closest to the power supply, while low-power devices can be placed farther from it.

- Signals, wherever possible, should be differential.

- Isolated power supplies require careful checking for parasitic, component, or internal PCB power plane capacitance that can allow AC present on input power or connectors to pass into the ground plane, or to any other internal signal. The AC might find a path back to its source via an I/O signal. While it can never be eliminated, it should be minimized as much as possible. The acceptable amount is implied by the design.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Vijayaraghavan, G.; Mark Brown; Malcolm Barnes (December 30, 2008). "8.11 Avoidance of earth loop". Electrical noise and mitigation - Part 3: Shielding and grounding (cont.), and filtering harmonics. EDN Network, UBM Tech. Retrieved March 24, 2014. External link in

|publisher=(help) - 1 2 3 4 Whitlock, Bill (2005). "Understanding, finding, and eliminating ground loops in audio and video systems" (PDF). Seminar Template. Jensen Transformers, Inc. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Robinson, Larry (2012). "About Ground Loops". MidiMagic. Larry Robinson personal website. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ Ballou, Glen (2008). Handbook for Sound Engineers (4 ed.). Taylor and Francis. pp. 1194–1196. ISBN 1136122532.

- ↑ Vijayaraghavan, G.; Mark Brown; Malcolm Barnes (December 30, 2008). "8.8.3 Magnetic or inductive coupling". Electrical noise and mitigation - Part 3: Shielding and grounding (cont.), and filtering harmonics. EDN Network, UBM Tech. Retrieved March 24, 2014. External link in

|publisher=(help) - 1 2 3 This type is often called "common impedance coupling", Ballou 2008 Handbook for Sound Engineers, 4th Ed., p. 1198-1200

External links

- Sound System Interconnection — from Rane Corporation

- Grounding and Shielding Audio Devices — from Rane Corporation

- Signal Purity — from Sound & Video Contractor

- Information technology in combination with medical devices Risks and solutions for electrical safety

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document "Federal Standard 1037C".

This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document "Federal Standard 1037C".