GSM

GSM (Global System for Mobile Communications, originally Groupe SpécialMobile), is a standard developed by the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) to describe the protocols for second-generation (2G) digital cellular networks used by mobile phones, first deployed in Finland in July 1991.[2] As of 2014 it has become the de facto global standard for mobile communications – with over 90% market share, operating in over 219 countries and territories.[3]

2G networks developed as a replacement for first generation (1G) analog cellular networks, and the GSM standard originally described a digital, circuit-switched network optimized for full duplex voice telephony. This expanded over time to include data communications, first by circuit-switched transport, then by packet data transport via GPRS (General Packet Radio Services) and EDGE (Enhanced Data rates for GSM Evolution or EGPRS).

Subsequently, the 3GPP developed third-generation (3G) UMTS standards followed by fourth-generation (4G) LTE Advanced standards, which do not form part of the ETSI GSM standard.

"GSM" is a trademark owned by the GSM Association. It may also refer to the (initially) most common voice codec used, Full Rate.

History

In 1982 work began to develop a European standard for digital cellular voice telecommunications when the European Conference of Postal and Telecommunications Administrations (CEPT) set up the Groupe Spécial Mobile committee and later provided a permanent technical-support group based in Paris. Five years later, in 1987, 15 representatives from 13 European countries signed a memorandum of understanding in Copenhagen to develop and deploy a common cellular telephone system across Europe, and EU rules were passed to make GSM a mandatory standard.[4] The decision to develop a continental standard eventually resulted in a unified, open, standard-based network which was larger than that in the United States.[5][6][7][8]

In February 1987 Europe produced the very first agreed GSM Technical Specification. Ministers from the four big EU countries cemented their political support for GSM with the Bonn Declaration on Global Information Networks in May and the GSM MoU was tabled for signature in September. The MoU drew-in mobile operators from across Europe to pledge to invest in new GSM networks to an ambitious common date. It got GSM up-and-running fast.

In this short 38-week period the whole of Europe (countries and industries) had been brought behind GSM in a rare unity and speed guided by four public officials: Armin Silberhorn (Germany), Stephen Temple (UK), Philippe Dupuis (France), and Renzo Failli (Italy).[9] In 1989, the Groupe Spécial Mobile committee was transferred from CEPT to the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI).[6][7][7][8]

In parallel, France and Germany signed a joint development agreement in 1984 and were joined by Italy and the UK in 1986. In 1986 the European Commission proposed reserving the 900 MHz spectrum band for GSM. The former Finnish prime minister Harri Holkeri made the world's first GSM call on July 1, 1991, calling Kaarina Suonio (mayor of the city of Tampere) using a network built by Telenokia and Siemens and operated by Radiolinja.[10] In the following year, 1992, saw the sending of the first short messaging service (SMS or "text message") message, and Vodafone UK and Telecom Finland signed the first international roaming agreement.

Work began in 1991 to expand the GSM standard to the 1800 MHz frequency band and the first 1800 MHz network became operational in the UK by 1993. Also that year, Telecom Australia became the first network operator to deploy a GSM network outside Europe and the first practical hand-held GSM mobile phone became available.

In 1995, fax, data and SMS messaging services were launched commercially, the first 1900 MHz GSM network became operational in the United States and GSM subscribers worldwide exceeded 10 million. In the same year, the GSM Association formed. Pre-paid GSM SIM cards were launched in 1996 and worldwide GSM subscribers passed 100 million in 1998.[7]

In 2000 the first commercial GPRS services were launched and the first GPRS-compatible handsets became available for sale. In 2001 the first UMTS (W-CDMA) network was launched, a 3G technology that is not part of GSM. Worldwide GSM subscribers exceeded 500 million. In 2002 the first Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS) were introduced and the first GSM network in the 800 MHz frequency band became operational. EDGE services first became operational in a network in 2003 and the number of worldwide GSM subscribers exceeded 1 billion in 2004.[7]

By 2005, GSM networks accounted for more than 75% of the worldwide cellular network market, serving 1.5 billion subscribers. In 2005 the first HSDPA-capable network also became operational. The first HSUPA network launched in 2007. (High-Speed Packet Access (HSPA) and its uplink and downlink versions are 3G technologies, not part of GSM.) Worldwide GSM subscribers exceeded three billion in 2008.[7]

The GSM Association estimated in 2010 that technologies defined in the GSM standard serve 80% of the global mobile market, encompassing more than 5 billion people across more than 212 countries and territories, making GSM the most ubiquitous of the many standards for cellular networks.[11]

Note that GSM is a second-generation (2G) standard employing Time-Division Multiple-Access (TDMA) spectrum-sharing, issued by the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI). The GSM standard does not include the 3G UMTS CDMA-based technology nor the 4G LTE OFDMA-based technology standards issued by the 3GPP.[12]

Telstra in Australia has shut down its 2G GSM network on December 1, 2016, which makes it the first mobile network operator to decommission a GSM network.[13] The second mobile provider planning to shut down its GSM network (on January 1, 2017) is AT&T Mobility from the United States.[14] Singapore will phase out 2G services by April 2017.

Technical details

Network structure

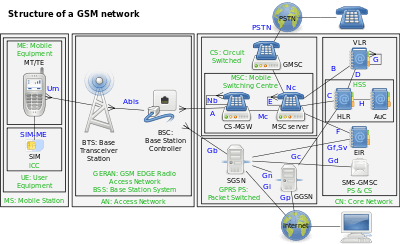

The network is structured into a number of discrete sections:

- Base Station Subsystem – the base stations and their controllers explained

- Network and Switching Subsystem – the part of the network most similar to a fixed network, sometimes just called the "core network"

- GPRS Core Network – the optional part which allows packet-based Internet connections

- Operations support system (OSS) – network maintenance

Base station subsystem

GSM is a cellular network, which means that cell phones connect to it by searching for cells in the immediate vicinity. There are five different cell sizes in a GSM network—macro, micro, pico, femto, and umbrella cells. The coverage area of each cell varies according to the implementation environment. Macro cells can be regarded as cells where the base station antenna is installed on a mast or a building above average rooftop level. Micro cells are cells whose antenna height is under average rooftop level; they are typically used in urban areas. Picocells are small cells whose coverage diameter is a few dozen metres; they are mainly used indoors. Femtocells are cells designed for use in residential or small business environments and connect to the service provider’s network via a broadband internet connection. Umbrella cells are used to cover shadowed regions of smaller cells and fill in gaps in coverage between those cells.

Cell horizontal radius varies depending on antenna height, antenna gain, and propagation conditions from a couple of hundred meters to several tens of kilometres. The longest distance the GSM specification supports in practical use is 35 kilometres (22 mi). There are also several implementations of the concept of an extended cell,[15] where the cell radius could be double or even more, depending on the antenna system, the type of terrain, and the timing advance.

Indoor coverage is also supported by GSM and may be achieved by using an indoor picocell base station, or an indoor repeater with distributed indoor antennas fed through power splitters, to deliver the radio signals from an antenna outdoors to the separate indoor distributed antenna system. These are typically deployed when significant call capacity is needed indoors, like in shopping centers or airports. However, this is not a prerequisite, since indoor coverage is also provided by in-building penetration of the radio signals from any nearby cell.

GSM carrier frequencies

GSM networks operate in a number of different carrier frequency ranges (separated into GSM frequency ranges for 2G and UMTS frequency bands for 3G), with most 2G GSM networks operating in the 900 MHz or 1800 MHz bands. Where these bands were already allocated, the 850 MHz and 1900 MHz bands were used instead (for example in Canada and the United States). In rare cases the 400 and 450 MHz frequency bands are assigned in some countries because they were previously used for first-generation systems.

Most 3G networks in Europe operate in the 2100 MHz frequency band. For more information on worldwide GSM frequency usage, see GSM frequency bands.

Regardless of the frequency selected by an operator, it is divided into timeslots for individual phones. This allows eight full-rate or sixteen half-rate speech channels per radio frequency. These eight radio timeslots (or burst periods) are grouped into a TDMA frame. Half-rate channels use alternate frames in the same timeslot. The channel data rate for all 8 channels is 270.833 kbit/s, and the frame duration is 4.615 ms.

The transmission power in the handset is limited to a maximum of 2 watts in GSM 850/900 and 1 watt in GSM 1800/1900.

Voice codecs

GSM has used a variety of voice codecs to squeeze 3.1 kHz audio into between 6.5 and 13 kbit/s. Originally, two codecs, named after the types of data channel they were allocated, were used, called Half Rate (6.5 kbit/s) and Full Rate (13 kbit/s). These used a system based on linear predictive coding (LPC). In addition to being efficient with bitrates, these codecs also made it easier to identify more important parts of the audio, allowing the air interface layer to prioritize and better protect these parts of the signal.

As GSM was further enhanced in 1997[16] with the Enhanced Full Rate (EFR) codec, a 12.2 kbit/s codec that uses a full-rate channel. Finally, with the development of UMTS, EFR was refactored into a variable-rate codec called AMR-Narrowband, which is high quality and robust against interference when used on full-rate channels, or less robust but still relatively high quality when used in good radio conditions on half-rate channel.

Subscriber Identity Module (SIM)

One of the key features of GSM is the Subscriber Identity Module, commonly known as a SIM card. The SIM is a detachable smart card containing the user's subscription information and phone book. This allows the user to retain his or her information after switching handsets. Alternatively, the user can also change operators while retaining the handset simply by changing the SIM. Some operators will block this by allowing the phone to use only a single SIM, or only a SIM issued by them; this practice is known as SIM locking.

Phone locking

Sometimes mobile network operators restrict handsets that they sell for use with their own network. This is called locking and is implemented by a software feature of the phone. A subscriber may usually contact the provider to remove the lock for a fee, utilize private services to remove the lock, or use software and websites to unlock the handset themselves. It is possible to hack past a phone locked by a network operator.

In some countries (e.g., Bangladesh, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Germany, Hong Kong, India, Iran, Lebanon, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, Poland, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand) all phones are sold unlocked.[17]

GSM security

GSM was intended to be a secure wireless system. It has considered the user authentication using a pre-shared key and challenge-response, and over-the-air encryption. However, GSM is vulnerable to different types of attack, each of them aimed at a different part of the network.[18]

The development of UMTS introduces an optional Universal Subscriber Identity Module (USIM), that uses a longer authentication key to give greater security, as well as mutually authenticating the network and the user, whereas GSM only authenticates the user to the network (and not vice versa). The security model therefore offers confidentiality and authentication, but limited authorization capabilities, and no non-repudiation.

GSM uses several cryptographic algorithms for security. The A5/1, A5/2, and A5/3 stream ciphers are used for ensuring over-the-air voice privacy. A5/1 was developed first and is a stronger algorithm used within Europe and the United States; A5/2 is weaker and used in other countries. Serious weaknesses have been found in both algorithms: it is possible to break A5/2 in real-time with a ciphertext-only attack, and in January 2007, The Hacker's Choice started the A5/1 cracking project with plans to use FPGAs that allow A5/1 to be broken with a rainbow table attack.[19] The system supports multiple algorithms so operators may replace that cipher with a stronger one.

Since 2000, different efforts have been done in order to crack the A5 encryption algorithms. Both A5/1 and A5/2 algorithms are broken, and their cryptanalysis has been considered in the literature. As an example, Karsten Nohl developed a number of rainbow tables (static values which reduce the time needed to carry out an attack) and have found new sources for known plaintext attacks.[20] He said that it is possible to build "a full GSM interceptor...from open-source components" but that they had not done so because of legal concerns.[21] Nohl claimed that he was able to intercept voice and text conversations by impersonating another user to listen to voicemail, make calls, or send text messages using a seven-year-old Motorola cellphone and decryption software available for free online.[22]

New attacks have been observed that take advantage of poor security implementations, architecture, and development for smartphone applications. Some wiretapping and eavesdropping techniques hijack the audio input and output providing an opportunity for a third party to listen in to the conversation.[23]

GSM uses General Packet Radio Service (GPRS) for data transmissions like browsing the web. The most commonly deployed GPRS ciphers were publicly broken in 2011.[24]

The researchers revealed flaws in the commonly used GEA/1 and GEA/2 ciphers and published the open-source "gprsdecode" software for sniffing GPRS networks. They also noted that some carriers do not encrypt the data (i.e., using GEA/0) in order to detect the use of traffic or protocols they do not like (e.g., Skype), leaving customers unprotected. GEA/3 seems to remain relatively hard to break and is said to be in use on some more modern networks. If used with USIM to prevent connections to fake base stations and downgrade attacks, users will be protected in the medium term, though migration to 128-bit GEA/4 is still recommended.

Standards information

The GSM systems and services are described in a set of standards governed by ETSI, where a full list is maintained.[25]

GSM open-source software

Several open-source software projects exist that provide certain GSM features:

- gsmd daemon by Openmoko[26]

- OpenBTS develops a Base transceiver station

- The GSM Software Project aims to build a GSM analyzer for less than $1,000[27]

- OsmocomBB developers intend to replace the proprietary baseband GSM stack with a free software implementation[28]

- YateBTS develops a Base transceiver station [29]

Issues with patents and open source

Patents remain a problem for any open-source GSM implementation, because it is not possible for GNU or any other free software distributor to guarantee immunity from all lawsuits by the patent holders against the users. Furthermore, new features are being added to the standard all the time which means they have patent protection for a number of years.

The original GSM implementations from 1991 may now be entirely free of patent encumbrances, however patent freedom is not certain due to the United States' "first to invent" system that was in place until 2012. The "first to invent" system, coupled with "patent term adjustment" can extend the life of a U.S. patent far beyond 20 years from its priority date. It is unclear at this time whether OpenBTS will be able to implement features of that initial specification without limit. As patents subsequently expire, however, those features can be added into the open-source version. As of 2011, there have been no lawsuits against users of OpenBTS over GSM use.

See also

- Cellular network

- Enhanced Data Rates for GSM Evolution (EDGE)

- High-Speed Downlink Packet Access (HSDPA)

- Long Term Evolution (LTE)

- Personal communications network (PCN)

- Nordic Mobile Telephone (NMT)

- International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI)

- MSISDN Mobile Subscriber ISDN Number

- Handoff

- Visitors Location Register (VLR)

- Um interface

- GSM-R (GSM-Railway)

- GSM services

- Cell Broadcast

- GSM localization

- Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS)

- NITZ Network Identity and Time Zone

- Wireless Application Protocol (WAP)

- Simulation of GSM networks

- Standards

- Comparison of mobile phone standards

- GEO-Mobile Radio Interface

- Intelligent Network

- Parlay X

- RRLP – Radio Resource Location Protocol

- GSM 03.48 – Security mechanisms for the SIM application toolkit

- RTP audio video profile

- Enhanced Network Selection (ENS)

- GSM frequency bands

- GSM USSD codes – Unstructured Supplementary Service Data: list of all standard GSM codes for network and SIM related functions

- GSM forwarding standard features codes – list of call forward codes working with all operators and phones

References

- ↑ Sauter, Martin (21 Nov 2013). "The GSM Logo: The Mystery of the 4 Dots Solved". Retrieved 23 Nov 2013.

[...] here's what [Yngve Zetterstrom, rapporteur of the Maketing and Planning (MP) group of the MoU (Memorandum of Understanding group, later to become the GSM Association (GSMA)) in 1989] had to say to solve the mystery: '[The dots symbolize] three [clients] in the home network and one roaming client.' There you go, an answer from the prime source!

- ↑ Anton A. Huurdeman, The Worldwide History of Telecommunications, John Wiley & Sons, 31 juli 2003, page 529

- ↑ "GSM Global system for Mobile Communications". 4G Americas. Retrieved 2014-03-22.

- ↑ EU Seeks To End Mandatory GSM for 900Mhz - Source

- ↑ Leader (7 September 2007). "Happy 20th Birthday, GSM". zdnet.co.uk. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 5 May 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

Before GSM, Europe had a disastrous mishmash of national analogue standards in phones and TV, designed to protect national industries but instead creating fragmented markets vulnerable to big guns from abroad.

- 1 2 "GSM". etsi.org. European Telecommunications Standards Institute. 2011. Archived from the original on 5 May 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

GSM was designed principally for voice telephony, but a range of bearer services was defined...allowing circuit-switched data connections at up to 9600 bits/s.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "History". gsmworld.com. GSM Association. 2001. Archived from the original on 5 May 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

1982 Groupe Speciale Mobile (GSM) is formed by the Confederation of European Posts and Telecommunications (CEPT) to design a pan-European mobile technology.

- 1 2 "Cellular History". etsi.org. European Telecommunications Standards Institute. 2011. Archived from the original on 5 May 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

The task was entrusted to a committee known as Groupe Spécial Mobile (GSMTM), aided by a "permanent nucleus" of technical support personnel, based in Paris.

- ↑ "Who created GSM?". Stephen Temple. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

Before GSM, Europe had a disastrous mishmash of national analogue standards in phones and TV, designed to protect national industries but instead creating fragmented markets vulnerable to big guns from abroad.

- ↑ "Maailman ensimmäinen GSM-puhelu" [World's first GSM call]. yle.fi. Yelisradio OY. 22 February 2008. Archived from the original on 5 May 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

Harri Holkeri made the first call on the Radiolinja (Elisa's subsidiary) network, at the opening ceremony in Helsinki on 07.01.1991.

- ↑ "GSM World statistics". gsmworld.com. GSM Association. 2010. Archived from the original on 21 May 2010. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ↑ "Mobile technologies GSM". Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ↑ "Telstra switches off GSM network". TeleGeography. 2016-12-02. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ "2G Sunset" (PDF). ATT Mobility. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ↑ Motorola Demonstrates Long Range GSM Capability – 300% More Coverage With New Extended Cell. Archived 19 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "GSM 06.51 version 4.0.1" (ZIP). ETSI. December 1997. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- ↑ Victoria Shannon (2007). "iPhone Must Be Offered Without Contract Restrictions, German Court Rules". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ↑ Solutions to the GSM Security Weaknesses, Proceedings of the 2nd IEEE International Conference on Next Generation Mobile Applications, Services, and Technologies (NGMAST2008), pp.576–581, Cardiff, UK, September 2008, arXiv:1002.3175

- ↑ "The A5/1 Cracking Project". http://www.scribd.com. Retrieved 3 Nov 2011.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help); External link in|publisher=(help) - ↑ Kevin J. O'Brien (28 December 2009). "Cellphone Encryption Code Is Divulged". New York Times.

- ↑ "A5/1 Cracking Project". Archived from the original on 25 December 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ↑ Owano, Nancy (27 Dec 2011). "GSM phones -- call them unsafe, says security expert". Archived from the original on 27 Dec 2011. Retrieved 27 Dec 2011.

Nohl said that he was able to intercept voice and text conversations by impersonating another user to listen to their voice mails or make calls or send text messages. Even more troubling was that he was able to pull this off using a seven-year-old Motorola cellphone and decryption software available free off the Internet.

- ↑ "cPanel". Infosecurityguard.com. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "Codebreaker Karsten Nohl: Why Your Phone Is Insecure By Design". Forbes.com. 12 August 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ "GSM UMTS 3GPP Numbering Cross Reference". ETSI. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ↑ "Gsmd – Openmoko". Wiki.openmoko.org. 8 February 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ↑ "The Hacker's Choice Wiki". Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "OsmocomBB". Bb.osmocom.org. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ↑ "YateBTS". Legba Inc. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

Further reading

- Redl, Siegmund M.; Weber, Matthias K.; Oliphant, Malcolm W (February 1995). An Introduction to GSM. Artech House. ISBN 978-0-89006-785-7.

- Redl, Siegmund M.; Weber, Matthias K.; Oliphant, Malcolm W (April 1998). GSM and Personal Communications Handbook. Artech House Mobile Communications Library. Artech House. ISBN 978-0-89006-957-8.

- Hillebrand, Friedhelm, ed. (December 2001). GSM and UMTS, The Creation of Global Mobile Communications. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-84322-2.

- Mouly, Michel; Pautet, Marie-Bernardette (June 2002). The GSM System for Mobile Communications. Telecom Publishing. ISBN 978-0-945592-15-0.

- Salgues, Salgues B. (April 1997). Les télécoms mobiles GSM DCS. Hermes (2nd ed.). Hermes Sciences Publications. ISBN 2866016068.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to GSM Standard. |

- GSM Association—Official industry trade group representing GSM network operators worldwide

- 3GPP—3G GSM standards development group