H-1B visa

The H-1B is a non-immigrant visa in the United States under the Immigration and Nationality Act, section 101(a)(15)(H). It allows U.S. employers to temporarily employ foreign workers in specialty occupations. If a foreign worker in H-1B status quits or is dismissed from the sponsoring employer, the worker must either apply for and be granted a change of status to another non-immigrant status, find another employer (subject to application for adjustment of status and/or change of visa), or leave the U.S.

The regulations define a "specialty occupation" as requiring theoretical and practical application of a body of highly specialized knowledge in a field of human endeavor[1] including but not limited to biotechnology, chemistry, architecture, engineering, mathematics, physical sciences, social sciences, medicine and health, education, law, accounting, business specialties, theology, and the arts, and requiring the attainment of a bachelor's degree or its equivalent as a minimum[2] (with the exception of fashion models, who must be "of distinguished merit and ability").[3] Likewise, the foreign worker must possess at least a bachelor's degree or its equivalent and state licensure, if required to practice in that field. H-1B work-authorization is strictly limited to employment by the sponsoring employer.

Structure of the program

Duration of stay

The duration of stay is three years, extendable to six years. An exception to maximum length of stay applies in certain circumstances:

- If a visa holder has submitted an I-140 immigrant petition or a labor certification prior to their fifth year anniversary of having the H-1B visa, they are entitled to renew their H-1B visa in one-year increments until a decision has been rendered on their application for permanent residence. This is backed up by the Immigration and Nationality Act 106a).[4]

- If the visa holder has an approved I-140 immigrant petition, but is unable to initiate the final step of the green card process due to their priority date not being current, they may be entitled to a three-year extension of their H-1B visa until their adjustment of status can finish. This exception originated with the American Competitiveness in the 21st Century Act of 2000 section 104a (AC21 104a).[4]

- The maximum duration of the H-1B visa is ten years for exceptional United States Department of Defense project related work.

A time increment of less than three years has sometimes applied to citizens of specific countries. For example, during her time as an H-1B visa holder, Melania Trump was limited to one year increments, which was the maximum time allowed then per H-1B visa for citizens of Slovenia, which Melania Trump was then a citizen of.[5]

H-1B holders who want to continue to work in the U.S. after six years, but who have not obtained permanent residency status, must remain outside of the U.S. for one year before reapplying for another H-1B visa if they do not qualify for one of the exceptions noted above allowing for extensions beyond six years.[6] Despite a limit on length of stay, no requirement exists that the individual remain for any period in the job the visa was originally issued for. This is known as H-1B portability or transfer, provided the new employer sponsors another H-1B visa, which may or may not be subjected to the quota. Under current law, H-1B visa has no stipulated grace period in the event the employer-employee relationship ceases to exist.

Congressional yearly numerical cap and exemptions

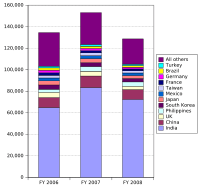

The current law limits to 65,000 the number of foreign nationals who may be issued a visa or otherwise provided H-1B status each fiscal year (FY). Laws exempt up to 20,000 foreign nationals holding a master's or higher degree from U.S. universities from the cap on H-1B visas. In addition, excluded from the ceiling are all H-1B non-immigrants who work at (but not necessarily for) universities, non-profit research facilities associated with universities, and government research facilities.[7] Universities can employ an unlimited number of foreign workers as cap-exempt. This also means that contractors working at but not directly employed by the institutions may be exempt from the cap as well. Free Trade Agreements carve out 1,400 H-1B1 visas for Chilean nationals and 5,400 H-1B1 visas for Singapore nationals. However, if these reserved visas are not used, then they are made available in the next fiscal year to applicants from other countries. Due to these unlimited exemptions and roll-overs, the number of H-1B visas issued each year is significantly more than the 65,000 cap, with 117,828 having been issued in FY2010, 129,552 in FY2011, and 135,991 in FY2012.[8][9] In past years, the cap was not always reached. For example, in FY1996, the INS (now known as USCIS) announced on August 20, 1996 that a preliminary report indicated that the cap had been exceeded, and processing of H-1B applications was temporarily halted. However, when more accurate numbers became available on September 6, it became apparent the cap had not been reached after all, and processing resumed for the remainder of the fiscal year.[10]

The United States Citizenship and Immigration Services starts accepting applications on the first business day of April for visas that count against the fiscal year starting in October. For instance, H-1B visa applications that count against the FY 2013 cap were submitted starting Monday, 2012 April 2. USCIS accepts H-1B visa applications no more than 6 months in advance of the requested start date.[11] Beneficiaries not subject to the annual cap are those who currently hold cap-subject H-1B status or have held cap-subject H-1B status at some point in the past six years.

Lottery

Each year, generally on April 1, the H-1B season commences for the following federal fiscal year; employment authorizations are granted on October 1. Due to a pre-employment application limit window of six months, the first weekday in April is the earliest that an applicant may legally apply for the next year's allotment of cap-subject H-1B.[11] H-1B "cap cases" are delineated on the envelope's label, preferably in red ink, with "Regular Cap" for the bachelor's degree, "C/S Cap" for H-1B1 treaty cases and "U.S. Master’"s for the U.S. master’s degrees or higher exemption.[12] USCIS publishes a memo when enough cap-subject applications have been received, indicating the closure of cap-subject application season,[13] the associated random selection process is often referred to as the H-1B lottery.[14] Those who have the U.S. master's exemption have two chances to be selected in the lottery: first, a lottery is held to award the 20,000 visas available to master's degree holders, and those not selected are then entered in the regular lottery for the other 65,000 visas. Those without a U.S. master's are entered only in the second, regular, lottery.[15]

Pro-H-1B pundits claim that the early closure, and number of applications received (172,500 in Fiscal Year 2015), are indications of employment demand and advocate increasing the 65,000 bachelor's degree cap.[16] David North, of the Center for Immigration Studies, claimed that unlike other immigration categories, H-1B filing fees, for applications which are not randomly selected, are refunded to the intending employer. However, applications that are not selected are simply returned unopened to the petitioner, with no money changing hands or refunded.

Computerworld and The New York Times have reported on the inordinate share of H-1B visas received by firms that specialize in offshore-outsourcing,[14] the subsequent inability of employers to hire foreign professionals with legitimate technical and language skill combinations,[17] and the outright replacement of American professionals already performing their job functions and being coerced to train their foreign replacements.[18][19]

- The United States Chamber of Commerce maintains a list of years when the random selection process (lottery) was implemented.[20]

Tax status of H-1B workers

The taxation of income for H-1B employees depends on whether they are categorized as either non-resident aliens or resident aliens for tax purposes. A non-resident alien for tax purposes is only taxed on income from the United States, while a resident alien for tax purposes is taxed on all income, including income from outside the US.

The classification is determined based on the "substantial presence test": If the substantial presence test indicates that the H-1B visa holder is a resident, then income taxation is like any other U.S. person and may be filed using Form 1040 and the necessary schedules; otherwise, the visa-holder must file as a non-resident alien using tax form 1040NR or 1040NR-EZ; he or she may claim benefit from tax treaties if they exist between the United States and the visa holder's country of citizenship.

Persons in their first year in the U.S. may choose to be considered a resident for taxation purposes for the entire year, and must pay taxes on their worldwide income for that year. This "First Year Choice" is described in IRS Publication 519 and can only be made once in a person's lifetime. A spouse, regardless of visa status, must include a valid Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN) or Social Security number (SSN) on a joint tax return with the H-1B holder.

Tax filing rules for H-1B holders may be complex, depending on the individual situation. Besides consulting a professional tax preparer knowledgeable about the rules for foreigners, the IRS Publication 519, U.S. Tax Guide for Aliens, may be consulted. Apart from state and federal taxes, H-1B visa holders pay Medicare and Social Security taxes, and are eligible for Social Security benefits.

Social Security and Medicare taxes

H-1B employees have to pay Social Security and Medicare taxes as part of their payroll. Like U.S. citizens, they are eligible to receive Social Security benefits even if they leave the United States, provided they have paid Social Security payroll taxes for at least 10 years. Further, the U.S. has bilateral agreements with several countries to ensure that the time paid into the U.S. Social Security system, even if it is less than 10 years, is taken into account in the foreign country's comparable system and vice versa.[21]

H-1B and path to permanent residency

Even though the H-1B visa is a non-immigrant visa, it is one of the few temporary visa categories recognized as dual intent, meaning an H-1B holder can have legal immigration intent (apply for and obtain the green card) while still a holder of the H-1B visa. Effectively, the requirement to maintain a foreign address for this non-immigrant classification was removed in the Immigration Act of 1990.[22]

In the past the employment-based green card process used to take only a few years, less than the duration of the H-1B visa itself. However, in recent times the legal employment-based immigration process has backlogged and retrogressed to the extent that it now takes many years for guest-work visa holders from certain countries to obtain green cards. Since the duration of the H-1B visa hasn't changed, this has meant that many more H-1B visa holders must renew their visas in one or three-year increments for continued legal status while their green card application is in process.

Dependents of H-1B visa holders

H-1B visa holders can bring immediate family members (spouse and children under 21) to the United States under the H-4 visa category as dependents.

An H-4 Visa holder may remain in the U.S. as long as the H-1B visa holder retains legal status. An H-4 visa holder is allowed to attend school, apply for a driver's license, and open a bank account in the United States.

Effective May 26, 2015, United States Citizenship and Immigration Services allows some spouses of H-1B visa holders to apply for eligibility to work in the United States.[23][24] The spouse would need to file Form I-765, Application for Employment Authorization, with supporting documents and the required filing fee.[24] The spouse is authorized to work in the United States only after the Form I-765 is approved and the spouse receives an Employment Authorization Document card.[24]

Administrative processing

When an H-1B worker travels outside the U.S. for any reason (other than to Canada or Mexico), he or she must have a valid visa stamped on his or her passport for re-entry in the United States. If the worker has an expired stamp but an unexpired i-797 petition, he or she will need to appear in a U.S. Embassy to get a new stamp. In some cases, H-1B workers can be required to undergo "administrative processing", involving extra background checks of different types. Under current rules, these checks are supposed to take ten days or less, but in some cases, have lasted years.[25]

Application process

The process of getting a H-1B visa has three stages:

- The employer files with the United States Department of Labor a Labor Condition Application (LCA) for the employee, making relevant attestations, including attestations about wages (showing that the wage is at least equal to the prevailing wage and wages paid to others in the company in similar positions) and working conditions.

- With an approved LCA, the employer files a Form I-129 (Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker) requesting H-1B classification for the worker. This must be accompanied by necessary supporting documents and fees.

- Once the Form I-129 is approved, the worker may begin working with the H-1B classification on or after the indicated start date of the job, if already physically present in the United States in valid status at the time. If the employee is outside the United States, he/she may use the approved Form I-129 and supporting documents to apply for the H-1B visa. With a H-1B visa, the worker may present himself or herself at a United States port of entry seeking admission to the United States, and get an Form I-94 to enter the United States. (Employees who started a job on H-1B status without a H-1B visa because they were already in the United States still need to get a H-1B visa if they ever leave and wish to reenter the United States while on H-1B status.)

OPT STEM extension and cap-gap extension

On April 2, 2008, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Secretary Michael Chertoff announced a 17-month extension to the OPT for students in qualifying STEM fields. Included in a rule change addressing the H-1B Cap-Gap, a short term loss of employment authorization between the F-1 visa and an approved H-1B, the OPT extension was included in the rule-change commonly referred to as the H-1B Cap-Gap Regulations.[26][27] The OPT extension only benefits foreign STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, or Mathematics) students, this opportunity is unavailable to foreign students of other disciplines. The 17 month work-authorization extension allows the foreign STEM student to work up to 29 months under the student visa, allowing the STEM student multiple years to obtain an H-1B visa.[28][29] To be eligible for the 12-month work-permit, any bachelor's degree in any field of study is valid. For the 17-month OPT extension, a student must have received a STEM degree in one of the approved majors listed on the USCIS website.[30] The STEM extension can be combined with the cap-gap extension.[31]

In 2014, a federal court denied the government's motion to dismiss the Washington Alliance of Technology Workers (Washtech) and three other plaintiff's case against the OPT STEM extension. Judge Huvelle noted that the plaintiffs had standing due to increased competition in their field, that the OPT participation had ballooned from 28,500 in 2008, to 123,000 and that while the students are working under OPT on student visas, employers are not required to pay Social Security and Medicare contributions, nor prevailing wage.[32]

Evolution of the program

Changes to legal and administrative rules

| Congress | Effect on fees | Effect on cap | Effect on LCA attestations and DOL investigative authority |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immigration Act of 1990, November 29, 1990, George H. W. Bush | |||

| 101st | Only a base filing fee | Set an annual cap of 65,000 on new 3-year H-1Bs, including transfer applications and extensions of stay. | Set up the basic rules for the Labor Condition Application |

| American Competitiveness and Workforce Improvement Act (ACWIA), October 21, 1998, Bill Clinton | |||

| 105th | Added a $500 fee that would be used to retrain U.S. workers and close the skill gap, in the hope of reducing subsequent need for H-1B visas. | Temporary increase in caps to 115,000 for 1999 and 2000[33] | Introduced the concept of "H-1B-dependent employer" and required additional attestations about non-displacement of U.S. workers from employers who were H-1B-dependent or had committed a willful misrepresentation in an application in the recent past. Also gave investigative authority to the United States Department of Labor. |

| American Competitiveness in the 21st Century Act, (AC21), October 17, 2000, Bill Clinton | |||

| 106th | Increased $500 fee for retraining US workers to $1000. | Increase in caps to 195,000 for Fiscal Years 2001, 2002, and 2003. Creation of an uncapped category for non-profit research institutions. Exemption from the cap for people who had already been cap-subject. This included people on cap-subject H-1Bs who were switching jobs, as well as people applying for a 3-year extension of their current 3-year H-1B. | |

| H-1B Visa Reform Act of 2004, part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2005, December 6, 2004, George W. Bush | |||

| 108th | Increased fee for retraining US workers to $1500 for companies with 26 or more employees, reduced to $750 for small companies. Added anti-fraud fee of $500 | Bachelor's degree cap returns to 65,000 with added 20,000 visas for applicants with U.S. postgraduate degrees. Additional exemptions for Non-profit research and governmental entities. | Expanded the Department of Labor's investigative authority, but also provided two standard lines of defense to employers (the Good Faith Compliance Defense and the Recognized Industry Standards Defense). |

| Employ American Workers Act, February 17, 2009, Barack Obama Part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (sunset on February 17, 2011) | |||

| 111th | No change. | No change. | All recipients of Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) or Federal Reserve Act Section 13 were required to file the additional attestations required of H-1B-dependent employers, for any employee who had not yet started on a H-1B visa. |

American Competitiveness in the Twenty-First Century Act of 2000

The American Competitiveness in the Twenty-First Century Act of 2000 (AC21) and the U.S. Department of Labor's PERM system for labor certification erased most of the earlier claimed arguments for H-1Bs as indentured servants during the green card process. With PERM, labor certification processing time is now approximately 9 months (as of Mar 2010).[34]

Because of AC21, the H-1B employee is free to change jobs if they have an I-485 application pending for six months and an approved I-140, and if the position they move to is substantially comparable to their current position. In some cases, if those labor certifications are withdrawn and replaced with PERM applications, processing times improve, but the person also loses their favorable priority date. In those cases, employers' incentive to attempt to lock in H-1B employees to a job by offering a green card is reduced, because the employer bears the high legal costs and fees associated with labor certification and I-140 processing, but the H-1B employee is still free to change jobs.

However, many people are ineligible to file I-485 at the current time due to the widespread retrogression in priority dates. Thus, they may well still be stuck with their sponsoring employer for many years. There are also many old labor certification cases pending under pre-PERM rules.

Consolidated Natural Resources Act of 2008

The Consolidated Natural Resources Act of 2008, which, among other issues, federalizes immigration in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), stipulates that during a transition period, numerical limitations do not apply to otherwise qualified workers in the H visa category in the CNMI and Guam.[35]

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009

On Feb. 17, 2009, President Obama signed into law the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (“stimulus bill”), Public Law 111-5.[36] Section 1661 of the ARRA incorporates the Employ American Workers Act (EAWA) by Senators Sanders (I-Vt.) and Grassley (R-Iowa) to limit certain banks and other financial institutions from hiring H-1B workers unless they had offered positions to equally or better-qualified U.S. workers, and to prevent banks from hiring H-1B workers in occupations they had laid off U.S. workers from. These restrictions include:

- The employer must, prior to filing the H-1B petition, take good-faith steps to recruit U.S. workers for the position for which the H-1B worker is sought, offering a wage at least as high as what the law requires for the H-1B worker. The employer must also attest that, in connection with this recruitment, it has offered the job to any U.S. worker who applies who is equally or better qualified for the position.

- The employer must not have laid off, and will not lay off, any U.S. worker in a job essentially equivalent to the H-1B position in the area of intended employment of the H-1B worker within the period beginning 90 days prior to the filing of the H-1B petition and ending 90 days after its filing.[37]

Changes in USCIS policy

After completing a policy review, the USCIS clarified that individuals who spent more than one year outside of U.S. and did not exhaust their entire six-year term can choose to be re-admitted for the "remainder" of initial six-year period without being subject to the H-1B cap.[38]

After completing a policy review, the USCIS clarified that, "Any time spent in H-4 status will not count against the six-year maximum period of admission applicable to H-1B aliens."[38]

USCIS recently issued a memorandum dated 8 Jan 2010. The memorandum effectively states that there must be a clear "employee employer relationship" between the petitioner (employer) and the beneficiary (prospective visa holder). It simply outlines what the employer must do to be considered in compliance as well as putting forth the documentation requirements to back up the employer's assertion that a valid relationship exists.

The memorandum gives three clear examples of what is considered a valid "employee employer relationship":

- a fashion model

- a computer software engineer working off-site/on-site

- a company or a contractor which is working on a co-production product in collaboration with DOD

In the case of the software engineer, the petitioner (employer) must agree to do (some of) the following among others:

- Supervise the beneficiary on and off-site

- Maintain such supervision through calls, reports, or visits

- Have a "right" to control the work on a day-to-day basis if such control is required

- Provide tools for the job

- Hire, pay, and have the ability to fire the beneficiary

- Evaluate work products and perform progress/performance reviews

- Claim them for tax purposes

- Provide (some type of) employee benefits

- Use "proprietary information" to perform work

- Produce an end product related to the business

- Have an "ability to" control the manner and means in which the worker accomplishes tasks

It further states that "common law is flexible" in how to weigh these factors. Though this memorandum cites legal cases and provides examples, such a memorandum in itself is not law and future memoranda could change this.

Protections for U.S. workers

Labor Condition Application

The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) is responsible for ensuring that foreign workers do not displace or adversely affect wages or working conditions of U.S. workers. For every H-1B petition filed with the USCIS, there must be included a Labor Condition Application (LCA) (not to be confused with the labor certification), certified by the U.S. Department of Labor. The LCA is designed to ensure that the wage offered to the non-immigrant worker meets or exceeds the "prevailing wage" in the area of employment. ("Immigration law has a number of highly technical terms that may not mean the same thing to the average reader."[39]) The LCA also contains an attestation section designed to prevent the program from being used to import foreign workers to break a strike or replace U.S. citizen workers.

While an employer is not required to advertise the position before hiring an H-1B non-immigrant pursuant to the H-1B visa approval, the employer must notify the employee representative about the Labor Condition Application (LCA)—or if there is no such representation, the employer must publish the LCA at the workplace and the employer's office. Under the regulations, LCAs are a matter of public record. Corporations hiring H-1B workers are required to make these records available to any member of the public who requests to look at them. Copies of the relevant records are also available from various web sites, including the Department of Labor.

History of the Labor Condition Application form

The LCA must be filed electronically using Form ETA 9035E.[40] Over the years, the complexity of the form increased from one page in 1997[41] to three pages in 2008,[42] to five pages as of August 2012.[43]

Employer attestations

By signing the LCA, the employer attests that:[44]

- The employer pays H-1B non-immigrants the same wage level paid to all other individuals with similar experience and qualifications for that specific employment, or the prevailing wage for the occupation in the area of employment, whichever is higher.

- The employment of H-1B non-immigrants does not adversely affect working conditions of workers similarly employed.

- On the date the application is signed and submitted, there is not a strike, lockout, or work stoppage in the course of a labor dispute in the occupation in which H-1B non-immigrants will be employed at the place of employment. If such a strike or lockout occurs after this application is submitted, the employer must notify ETA within three days, and the application is not used to support petition filings with INS for H-1B non-immigrants to work in the same occupation at the place of employment until ETA determines the strike or lockout is over.

- A copy of this application has been, or will be, provided to each H-1B non-immigrant employed pursuant to this application, and, as of the application date, notice of this application has been provided to workers employed in the occupation in which H-1B non-immigrants will be employed:

- Notice of this filing has been provided to bargaining representative of workers in the occupation in which H-1B non-immigrants will be employed; or

- There is no such bargaining representative; therefore, a notice of this filing has been posted and was, or will remain, posted for 10 days in at least two conspicuous locations where H-1B non-immigrants will be employed.

The law requires H-1B workers to be paid the higher of the prevailing wage for the same occupation and geographic location, or the same as the employer pays to similarly situated employees. Other factors, such as age and skill were not permitted to be taken into account for the prevailing wage. Congress changed the program in 2004 to require the Department of Labor to provide four skill-based prevailing wage levels for employers to use. This is the only prevailing wage mechanism the law permits that incorporates factors other than occupation and location.

The approval process for these applications are based on employer attestations and documentary evidence submitted. The employer is advised of their liability if they are replacing a U.S. worker.

Limits on employment authorization

USCIS clearly states the following concerning H-1B nonimmigrants' employment authorization.

| “ | H-1B nonimmigrants may only work for the petitioning U.S. employer and only in the H-1B activities described in the petition. The petitioning U.S. employer may place the H-1B worker on the worksite of another employer if all applicable rules (e.g., Department of Labor rules) are followed. Generally, a nonimmigrant employee may work for more than one employer at the same time. However, each employer must follow the process for initially applying for a nonimmigrant employee.[45] | ” |

When a H-1B nonimmigrant works with multiple employers, if any of employers fail to file the petition, it is considered as an unauthorized employment and the nonimmigrant fails to maintain the status.

H-1B fees earmarked for U.S. worker education and training

In 2007, the U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration (ETA), reported on two programs, the High Growth Training Initiative and Workforce Innovation Regional Economic Development (WIRED), which have received or will receive $284 million and $260 million, respectively, from H-1B training fees to educate and train U.S. workers. According to the Seattle Times $1 billion from H1-B fees have been distributed by the Labor Department to further train the U.S. workforce since 2001.[46]

Criticisms of the program

The H-1B program has been criticized on many grounds. It was the subject of a hearing, "Immigration Reforms Needed to Protect Skilled American Workers," by the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary on March 17, 2015.[47][48] According to Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa, chairman of the committee:

| “ | The program was intended to serve employers who could not find the skilled workers they needed in the United States. Most people believe that employers are supposed to recruit Americans before they petition for an H-1B worker. Yet, under the law, most employers are not required to prove to the Department of Labor that they tried to find an American to fill the job first. And, if there is an equally or even better qualified U.S. worker available, the company does not have to offer him or her the job. Over the years the program has become a government-assisted way for employers to bring in cheaper foreign labor, and now it appears these foreign workers take over – rather than complement – the U.S. workforce.[49] | ” |

According to the editorial board of The New York Times, speaking in June 2015, loopholes and lax enforcement of the H-1B visa program has resulted in exploitation of both visa holders and American workers.[50]

Use for outsourcing

In some cases, rather than being used to hire talented workers not available in the American labor market, the program is being used for outsourcing.[51] Senators Dick Durbin and Charles Grassley of Iowa began introducing "The H-1B and L-1 Visa Fraud & Prevention Act" in 2007. According to Durbin, speaking in 2009, "The H-1B visa program should complement the U.S. workforce, not replace it;" "The…program is plagued with fraud and abuse and is now a vehicle for outsourcing that deprives qualified American workers of their jobs." The proposed legislation has been opposed by Compete America, a tech industry lobbying group,[52] Outsourcing firms, many based in India, are major users of H-1B visas. The out-sourcing firm contracts with an employer, such as Disney, to perform technical services. Disney then closes down its in-house department and lays off its employees. The outsourcing firm then performs the work.[53]

In June 2015 congressional leaders announced that the Department of Labor had opened an investigation of outsourcing of technical tasks by Southern California Edison to Tata Consultancy Services and Infosys then laying off 500 technology workers.[54]

No labor shortages

Paul Donnelly, in a 2002 article in Computerworld, cited Milton Friedman as stating that the H-1B program acts as a subsidy for corporations.[55] Others holding this view include Dr. Norman Matloff, who testified to the U.S. House Judiciary Committee Subcommittee on Immigration on the H-1B subject.[56] Matloff's paper for the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform claims that there has been no shortage of qualified American citizens to fill American computer-related jobs, and that the data offered as evidence of American corporations needing H-1B visas to address labor shortages was erroneous.[57] The United States General Accounting Office found in a report in 2000 that controls on the H-1B program lacked effectiveness.[58] The GAO report's recommendations were subsequently implemented.

High-tech companies often cite a tech-worker shortage when asking Congress to raise the annual cap on H-1B visas, and have succeeded in getting various exemptions passed. The American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA), described the situation as a crisis, and the situation was reported on by the Wall Street Journal, BusinessWeek and Washington Post. Employers applied pressure on Congress.[59] Microsoft chairman Bill Gates testified in 2007 on behalf of the expanded visa program on Capitol Hill, "warning of dangers to the U.S. economy if employers can't import skilled workers to fill job gaps".[59] Congress considered a bill to address the claims of shortfall[60] but in the end did not revise the program.[61]

According to a study conducted by John Miano and the Center for Immigration Studies, there is no empirical data to support a claim of employee worker shortage.[62] Citing studies from Duke, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, Georgetown University and others, critics have also argued that in some years, the number of foreign programmers and engineers imported outnumbered the number of jobs created by the industry.[63] Organizations have also posted hundreds of first hand accounts of H-1B Visa Harm reports directly from individuals negatively impacted by the program, many of whom are willing to speak with the media.[64]

Studies carried out from the 1990s through 2011 by researchers from Columbia U, Computing Research Association (CRA), Duke U, Georgetown U, Harvard U, National Research Council of the NAS, RAND Corporation, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rutgers U, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, Stanford U, SUNY Buffalo, UC Davis, UPenn Wharton School, Urban Institute, and U.S. Dept. of Education Office of Education Research & Improvement have reported that the U.S. has been producing sufficient numbers of able and willing STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) workers, while several studies from Hal Salzman, B. Lindsay Lowell, Daniel Kuehn, Michael Teitelbaum and others have concluded that the U.S. has been employing only 30% to 50% of its newly degreed able and willing STEM workers to work in STEM fields. A 2012 IEEE announcement of a conference on STEM education funding and job markets stated "only about half of those with under-graduate STEM degrees actually work in the STEM-related fields after college, and after 10 years, only some 8% still do".[65]

Ron Hira, a professor of public policy at Howard University and a longtime critic of the H-1B visa program, recently called the IT talent shortage "imaginary,"[66] a front for companies that want to hire relatively inexpensive foreign guest workers.

Wage depression

Wage depression is a chronic complaint critics have about the H-1B program:The Department of Homeland Security annual report indicates that H1-B workers in the field of Computer Science are paid a mean salary of $75,000 annually (2014) almost 25,000 dollars below the average annual income for software Developers [67]and studies have found that H-1B workers are paid significantly less than U.S. workers.[68][69] It is claimed[70][71][72][73][74][75] that the H-1B program is primarily used as a source of cheap labor. A paper by George J. Borjas for the National Bureau of Economic Research found that "a 10 percent immigration-induced increase in the supply of doctorates lowers the wage of competing workers by about 3 to 4 percent."[76] A 2016 study found that H-1B visas kept wages for US computer scientists 2.6-5.1% lower, and employment in computer science for US workers 6.1-10.8% lower, but caused greater production efficiency, lowered the prices of IT products, raised the output of IT products and caused substantially higher profits for IT firms.[77]

The Labor Condition Application (LCA) included in the H-1B petition is supposed to ensure that H-1B workers are paid the prevailing wage in the labor market, or the employer's actual average wage (whichever is higher), but evidence exists that some employers do not abide by these provisions and avoid paying the actual prevailing wage despite stiff penalties for abusers.[78]

Theoretically, the LCA process appears to offer protection to both U.S. and H-1B workers. However, according to the U.S. General Accounting Office, enforcement limitations and procedural problems render these protections ineffective.[79] Ultimately, the employer, not the Department of Labor, determines what sources determine the prevailing wage for an offered position, and it may choose among a variety of competing surveys, including its own wage surveys, provided that such surveys follow certain defined rules and regulations.

The law specifically restricts the Department of Labor's approval process of LCAs to checking for "completeness and obvious inaccuracies".[80] In FY 2005, only about 800 LCAs were rejected out of over 300,000 submitted. Hire Americans First has posted several hundred first hand accounts of individuals negatively impacted by the program, many of whom are willing to speak with the media.[64]

According to attorney John Miano, the H-1B prevailing wage requirement is "rife" with loopholes.[81] Ron Hira, assistant professor of public policy at the Rochester Institute of Technology, compiled the median wage in 2005 for new H-1B information technology (IT), these wages were found to $50,000, lower than starting wages for IT graduates with a B.S. degree. The U.S. government OES office's data indicates that 90% of H-1B IT wages were below the median U.S. wage and 62% in the 25th percentile for the same occupation.[81]

In 2002, the U.S. government began an investigation into Sun Microsystems' hiring practices after an ex-employee, Guy Santiglia, filed complaints with the U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. Department of Labor alleging that the Santa Clara firm discriminates against American citizens in favor of foreign workers on H-1B visas. Santiglia accused the company of bias against U.S. citizens when it laid off 3,900 workers in late 2001 and at the same time applied for thousands of visas. In 2002, about 5 percent of Sun's 39,000 employees had temporary work visas, he said.[82] In 2005, it was decided that Sun violated only minor requirements and that neither of these violations was substantial or willful. Thus, the judge only ordered Sun to change its posting practices.[83]

Additionally, because H1-B workers are sometimes forced to work 80 hours and sometimes more than 100 hours per week the savings in wages are more than is first apparent. In a case in Torrance California, an American employee attempted to intervene because he was concerned the H1-B employee was literally being worked to death, as he had been worked 120 hours a week for a period of months. Fearing for his job the H1-B worker attempted to stop the American employee from helping him. This same company described the reasons they liked H1-B employees is that beyond their wages being lower, they are "Docile".

2016 presidential election and the H-1B visa

With immigration weighing heavily on the 2016 presidential election, the H-1B visa has gained critical focus. According to Computerworld, Donald Trump has taken a stance to "pause" and re-write the H-1B system.[84] Additionally, during some of his rallies he has invited guest speakers to raise awareness of the hundreds of IT workers who have been displaced by H-1B guest workers. Hillary Clinton on the other hand, has supported an increase of the H-1B visa cap from 65,000 to 195,000.[85]

Risks for employees

Historically, H-1B holders have sometimes been described as indentured servants,[86] and while the comparison is no longer as compelling, it had more validity prior to the passage of American Competitiveness in the Twenty-First Century Act of 2000. Although immigration generally requires short- and long-term visitors to disavow any ambition to seek the green card (permanent residency), H-1B visa holders are an important exception, in that the H-1B is legally acknowledged as a possible step towards a green card under what is called the doctrine of dual intent.

H-1B visa holders may be sponsored for their green cards by their employers through an Application for Alien Labor Certification, filed with the U.S. Department of Labor. In the past, the sponsorship process has taken several years, and for much of that time the H-1B visa holder was unable to change jobs without losing their place in line for the green card. This created an element of enforced loyalty to an employer by an H-1B visa holder. Critics alleged that employers benefit from this enforced loyalty because it reduced the risk that the H-1B employee might leave the job and go work for a competitor, and that it put citizen workers at a disadvantage in the job market, since the employer has less assurance that the citizen will stay at the job for an extended period of time, especially if the work conditions are tough, wages are lower or the work is difficult or complex. It has been argued that this makes the H-1B program extremely attractive to employers, and that labor legislation in this regard has been influenced by corporations seeking and benefiting from such advantages.

Some recent news reports suggest that the recession that started in 2008 will exacerbate the H-1B visa situation, both for supporters of the program and for those who oppose it.[87] The process to obtain the green card has become so long that during these recession years it has not been unusual that sponsoring companies fail and disappear, thus forcing the H-1B employee to find another sponsor, and lose their place in line for the green card. An H-1B employee could be just one month from obtaining their green card, but if the employee is laid off, he or she may have to leave the country, or go to the end of the line and start over the process to get the green card, and wait as much as 15 more years, depending on the nationality and visa category.[88]

The American Competitiveness in the Twenty-First Century Act of 2000 provides some relief for people waiting for a long time for a green card, by allowing H-1B extensions past the normal 6 years, as well as by making it easier to change the sponsoring employer.

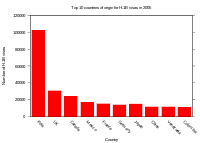

The out-sourcing/off-shoring visa

In his floor statement on H-1B Visa Reform, Senator Dick Durbin stated "The H-1B job visa lasts for three years and can be renewed for three years. What happens to those workers after that? Well, they could stay. It is possible. But these new companies have a much better idea for making money. They send the engineers to America to fill spots—and get money to do it—and then after the three to six years, they bring them back to work for the companies that are competing with American companies. They call it their outsourcing visa. They are sending their talented engineers to learn how Americans do business and then bring them back and compete with those American companies."[89] Critics of H-1B use for outsourcing have also noted that more H-1B visas are granted to companies headquartered in India than companies headquartered in the United States.[90]

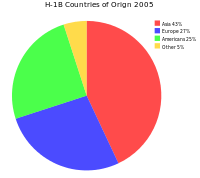

Of all computer systems analysts and programmers on H-1B visas in the U.S., 74 percent were from Asia. This large scale migration of Asian IT professionals to the United States has been cited as a central cause for the quick emergence of the offshore outsourcing industry.[91]

In FY 2009, due to the worldwide recession, applications for H-1B visas by off-shore out-sourcing firms were significantly lower than in previous years,[92] yet 110,367 H-1B visas were issued, and 117,409 were issued in FY2010.

Departure requirement on job loss

If an employer lays off an H-1B worker, the employer is required to pay for the laid-off worker's transportation outside the United States.

If an H-1B worker is laid off for any reason, the H-1B program technically does not specify a time allowance or grace period to round up one's affairs irrespective of how long the H-1B worker might have lived in the United States. To round up one's affairs, filing an application to change to another non-immigrant status may therefore become a necessity.

If an H-1B worker is laid off and attempts to find a new H-1B employer to file a petition for him, the individual is considered out of status if there is even a one-day gap between the last day of employment and the date that the new H-1B petition is filed. While some attorneys claim that there is a grace period of thirty days, sixty days, or sometimes ten days, that is not true according to the law. In practice, USCIS has accepted H-1B transfer applications even with a gap in employment up to 60 days, but that is by no means guaranteed.

Some of the confusion regarding the alleged grace period arose because there is a 10-day grace period for an H-1B worker to depart the United States at the end of his authorized period of stay (does not apply for laid-off workers). This grace period only applies if the worker works until the H-1B expiration date listed on his I-797 approval notice, or I-94 card. 8 CFR 214.2(h)(13)(i)(A).

American workers are ordered to train their foreign replacements

There have been cases where employers used the program to replace their American employees with H-1B employees, and in some of those cases, the American employees were even ordered to train their replacements.[51][53][93]

Age discrimination

In Fiscal Year 2014, 72% of H-1B holders were between the ages of 25 and 34, according to the USCIS "Characteristics of Specialty Occupation Workers (H-1B): Fiscal Year 2014", Table 5 of the report denotes that only 3,592 of the 315,857 H-1B visas were approved for workers over the age of 50.[94] Computerworld has reported on H-1B age discrimination within the program,[95] and in the case against Disney World's H-1B replacement tactic, age discrimination is an aspect of 2015 court filings.[96]

Fraud

The United States Citizenship and Immigration Services "H-1B Benefit Fraud & Compliance Assessment" of September 2008 concluded 21% of H-1B visas granted originate from fraudulent applications or applications with technical violations.[97] Fraud was defined as a willful misrepresentation, falsification, or omission of a material fact. Technical violations, errors, omissions, and failures to comply that are not within the fraud definition were included in the 21% rate.[98] Subsequently, USCIS has made procedural changes to reduce the number of fraud and technical violations on H-1B applications.

| Beneficiary Education Level | Violation Rate | % of Sample | Total Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bachelor's Degree | 31% | 43% | 106 |

| Graduate Degree | 13% | 57% | 140 |

| Reported Occupations | Violation Rate | % of Sample | Total Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Architecture, Engineering, and Surveying | 8% | 15% | 36 |

| Mathematics and Physical Sciences | 0% | 1% | 3 |

| Computer Professionals | 27% | 42% | 104 |

| Life Sciences | 0% | 4% | 11 |

| Social Sciences | 0% | <1% | 1 |

| Medicine and Health | 10% | 4% | 10 |

| Education | 9% | 13% | 33 |

| Law | 0% | <1% | 1 |

| Writing | 0% | <1% | 1 |

| Art | 29% | 3 | 7 |

| Accounting, Human Resources, Sales, Advertising, and Business Analysts | 42% | 11% | 26 |

| Managerial | 33% | 4% | 9 |

| Miscellaneous Professions | 0% | 2% | 4 |

In 2009, federal authorities busted a nationwide H-1B visa scam.[99]

Fraud has included acquisition of a fake university degree for the prospective H-1B worker, coaching the worker on lying to consul officials, hiring a worker for which there is no U.S. job, charging the worker money to be hired, benching the worker with no pay, and taking a cut of the worker's U.S. salary. The workers, who have little choice in the matter, are also engaged in fraud, and may be charged, fined, and deported.[100]

Abuse

Some workers who come to the US on H-1B visas receive poor, unfair, and illegal treatment by brokers who place them with jobs in the US, according to a report published in 2014.[101][102] The United States Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2013 was passed to help protect the rights of foreign workers in the U.S., and the US Department of State distributes pamphlets to inform foreign workers of their rights.[103]

Similar programs

In addition to H-1B visas, there are a variety of other visa categories that allow foreign workers to come into the U.S. to work for some period of time.

L-1 visas are issued to foreign employees of a corporation. Under recent rules, the foreign worker must have worked for the corporation for at least one year in the preceding three years prior to getting the visa. An L-1B visa is appropriate for non-immigrant workers who are being temporarily transferred to the United States based on their specialized knowledge of the company's techniques and methodologies. An L-1A visa is for managers or executives who either manage people or an essential function of the company. There is no requirement to pay prevailing wages for the L-1 visa holders. For Canadian residents, a special L visa category is available.

TN-1 visas are part of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and are issued to Canadian and Mexican citizens.[104] TN visas are only available to workers who fall into one of a pre-set list of occupations determined by the NAFTA treaty. There are specific eligibility requirements for the TN Visa.

E-3 visas are issued to citizens of Australia under the Australia free-trade treaty.

H-1B1 visas are a sub-set of H-1B issued to residents of Chile and Singapore under the United States-Chile Free Trade Agreement of 2003; PL108-77 § 402(a)(2)(B), 117 Stat. 909, 940; S1416, HR2738; passed in House 2003-07-24 and the United States-Singapore Free Trade Agreement of 2003; PL108-78 § 402(2), 117 Stat. 948, 970-971; S1417, HR2739; passed in House 2003-07-24, passed in senate 2003-07-31, signed by executive (GWBush) 2003-05-06. According to USCIS, unused H-1B1 visas are added into the next year's H-1B base quota of 58,200.

One recent trend in work visas is that various countries attempt to get special preference for their nationals as part of treaty negotiations. Another trend is for changes in immigration law to be embedded in large Authorization or Omnibus bills to avoid the controversy that might accompany a separate vote.

H-2B visa: The H-2B non-immigrant program permits employers to hire foreign workers to come to the U.S. and perform temporary nonagricultural work, which may be one-time, seasonal, peak load or intermittent. There is a 66,000 per year limit on the number of foreign workers who may receive H-2B status.

H-1B demographics and tables

H-1B applications approved

| Year | Initial employment approvals | Continuing employment approvals | Total |

| 1999 | 134,411 | na | na |

| 2000 | 136,787 | 120,853 | 257,640 |

| 2001 | 201,079 | 130,127 | 331,206 |

| 2002 | 103,584 | 93,953 | 197,537 |

| 2003 | 105,314 | 112,026 | 217,340 |

| 2004 | 130,497 | 156,921 | 287,418 |

| 2005 | 116,927 | 150,204 | 267,131 |

| 2006 | 109,614 | 161,367 | 270,981 |

| 2007 | 120,031 | 161,413 | 281,444 |

| 2008 | 109,335 | 166,917 | 276,252 |

| 2009 | 86,300 | 127,971 | 214,271 |

| 2010 | 76,627 | 116,363 | 192,990 |

| 2011 | 106,445 | 163,208 | 269,653 |

| 2012 | 136,890 | 125,679 | 262,569 |

| 2013 | 128,291 | 158,482 | 286,773 |

| 2014 | 124,326 | 191,531 | 315,857 |

| Year | No HS Diploma | Only HS Diploma | Less Than 1 year of College | 1+ years of College | Equivalent of Associate's | Total Less Than Equivalent of U.S. Bachelor's |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 554 | 288 | 158 | 1,290 | 696 | 2,986 |

| 2001 | 247 | 895 | 284 | 1,376 | 1,181 | 3,983 |

| 2002 | 169 | 806 | 189 | 849 | 642 | 2,655 |

| 2003 | 148 | 822 | 122 | 623 | 534 | 2,249 |

| 2004 | 123 | 690 | 137 | 421 | 432 | 1,803 |

| 2005 | 107 | 440 | 77 | 358 | 363 | 1,345 |

| 2006 | 96 | 392 | 54 | 195 | 177 | 914 |

| 2007 | 72 | 374 | 42 | 210 | 215 | 913 |

| 2008 | 80 | 174 | 19 | 175 | 195 | 643 |

| 2009 | 108 | 190 | 33 | 236 | 262 | 829 |

| 2010 | 140 | 201 | 24 | 213 | 161 | 739 |

| 2011 | 373 | 500 | 44 | 255 | 170 | 1,342 |

| 2012 | 108 | 220 | 35 | 259 | 174 | 796 |

| 2013 | 68 | 148 | 15 | 162 | 121 | 514 |

| 2014 | 32 | 133 | 18 | 133 | 88 | 404 |

H-1B visas issued per year

| Year | H-1B | H-1B1 | Total |

| 1990 | 794 | na | 794 |

| 1991 | 51,882 | na | 51,882 |

| 1992 | 44,290 | na | 44,290 |

| 1993 | 35,818 | na | 35,818 |

| 1994 | 42,843 | na | 42,843 |

| 1995 | 51,832 | na | 51,832 |

| 1996 | 58,327 | na | 58,327 |

| 1997 | 80,547 | na | 80,547 |

| 1998 | 91,360 | na | 91,360 |

| 1999 | 116,513 | na | 116,513 |

| 2000 | 133,290 | na | 133,290 |

| 2001 | 161,643 | na | 161,643 |

| 2002 | 118,352 | na | 118,352 |

| 2003 | 107,196 | na | 107,196 |

| 2004 | 138,965 | 72 | 139,037 |

| 2005 | 124,099 | 275 | 124,374 |

| 2006 | 135,421 | 440 | 135,861 |

| 2007 | 154,053 | 639 | 154,692 |

| 2008 | 129,464 | 719 | 130,183 |

| 2009 | 110,367 | 621 | 110,988 |

| 2010 | 117,409 | 419 | 117,828 |

| 2011 | 129,134 | 418 | 129,552 |

| 2012 | 135,530 | 461 | 135,991 |

| 2013 | 153,223 | 571 | 153,794 |

| 2014 | 161,369 | 870 | 162,239 |

Top H-1B employers by visas approved

|

| School | H-1Bs Received 2006 |

| New York City Public Schools | 642 |

| University of Michigan | 437 |

| University of Illinois at Chicago | 434 |

| University of Pennsylvania | 432 |

| Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine | 432 |

| University of Maryland | 404 |

| Columbia University | 355 |

| Yale University | 316 |

| Harvard University | 308 |

| Stanford University | 279 |

| Washington University in St. Louis | 278 |

| University of Pittsburgh | 275 |

See also

Notes

- ↑ "8 U.S. Code § 1184 - Admission of non immigrants". LII / Legal Information Institute.

- ↑ "8 U.S. Code § 1184 - Admission of non-immigrants". LII / Legal Information Institute.

- ↑ "8 U.S. Code § 1101 - Definitions". LII / Legal Information Institute.

- 1 2 "7th Year H-1B Extensions Under AC21 104(c) and 106(a) – Statutes and USCIS Guidance - The Visa Bulletin".

- ↑ Stahl, Jeremy (September 14, 2016). "Looks Like the Melania Trump Immigration Story Was a Case of Bad Reporting". Slate. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- ↑ "H-1B Visa". Harvard University. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- ↑ American Competitiveness in the 21st Century Act, Pub. L.No.106-313, 114 Stat.1251, 2000 S. 2045; Pub. L. No. 106-311, 114 Stat. 1247 (2000 Oct 17), 2000 HR5362; 146 Cong. Rec. H9004-06 (2000 October 5)

- ↑ FY2011

- ↑ FY2012

- ↑ "INS Statement on H-1B Visa Cap". American Immigration Lawyers Association. September 16, 1996. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- 1 2 "H-1B Fiscal Year (FY) 2013 Cap Season". USCIS. Archived from the original on 2011-08-18. Retrieved 2012-05-28.

H-1B petitions can be filed no more than six months in advance of the requested start date. Therefore, petitions seeking an FY2010 H-1B Cap number with an 2009 Oct. 1 start date can be filed no sooner than 2009 April 1.

- ↑ "H-1B Fiscal Year (FY) 2016 Cap Season". USCIS. Archived from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ↑ "USCIS Reaches FY 2015 H-1B Cap". U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). 10 April 2014. Archived from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- 1 2 Patrick Thibodeau; Sharon Machlis (30 July 2015). "Despite H-1B lottery, offshore firms dominate visa use". ComputerWorld. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

With the exception of a few tech firms -- notably Microsoft, Google, Amazon and Oracle -- the top 25 H-1B-using firms are either based in India or are U.S. firms running large offshore operations.

- ↑ "USCIS Reaches FY 2017 H-1B Cap". USCIS. April 7, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- ↑ Raif Karerat (14 April 2015). "Increase the cap on H-1B visas: Todd Schulte of FWD.us". The American Bazaar. Archived from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ↑ Julia, Preston (10 November 2015). "Large Companies Game H-1B Visa Program, Costing the U.S. Jobs". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ↑ Patrick Thibodeau (28 January 2016). "Laid-off IT workers muzzled as H-1B debate heats up". ComputerWorld. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

That clause has kept former Eversource employees from speaking out because of fears the utility will sue them if they say anything about their experience. The IT firms that Eversource uses, Infosys and Tata Consultancy Services, are major users of the H-1B visa

- ↑ JULIA PRESTON (3 June 2015). "Pink Slips at Disney. But First, Training Foreign Replacements.". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

Instead, about 250 Disney employees were told in late October that they would be laid off. Many of their jobs were transferred to immigrants on temporary visas for highly skilled technical workers, who were brought in by an outsourcing firm based in India.

- ↑ "H - 1B Petition Data FY1992 – Present" (PDF). immigration.uschamber.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ↑ "International Programs - International Agreements".

- ↑ Henry J. Chang. "Immigrant Intent and the Dual Intent Doctrine". Archived from the original on 29 February 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

The exemption of H-1 and L nonimmigrants from the presumption of immigrant intent resulted from §205(b)(1) of the Immigration Act of 1990 ("IMMACT 90"), Pub. L. No. 101-649, 104 Stat. 4978; effective October 1, 1991. While the requirement to maintain an unabandoned foreign residence abroad never applied to L nonimmigrants, §205(e) of IMMACT 90 eliminated the foreign residence requirement for H-1 nonimmigrants.

- ↑ Iyengar, Rishi. "Dependent Spouses of Highly Skilled Immigrant Workers to Get Work Permits". Time. February 25, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "DHS Extends Eligibility for Employment Authorization to Certain H-4 Dependent Spouses of H-1B Nonimmigrants Seeking Employment-Based Lawful Permanent Residence". United States Department of Homeland Security. February 24, 2015.

- ↑ Alden, Edward (10 April 2011). "America's 'National Suicide'". Newsweek. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ↑ "Extension of Post Completion Optional Practical Training (OPT) and F-1 Status for Eligible Students under the H-1B Cap-Gap Regulations". Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ↑ Chad C. Haddal (28 April 2008). "Foreign Students in the United States: Policies and Legislation" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. p. CRS-23. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

In addition to the OPT extension, the US CIS rule change also addresses the commonly referred to “cap-gap” for H-1B nonimmigrant employment authorization. The cap-gap occurs when the period of admission for an F-1 student with an approved H-1B petition expires before the start date of the H-1B employment, thus creating a gap between the end of the F-1 status and beginning of the H-1B status. Under previous regulations, USCIS could authorize extensions for students caught in a cap-gap, but only when the H-1B cap was likely to be reached by the end of the fiscal year.

- ↑ "Federal Register, Volume 73, Number 68 (April 8, 2008)". April 2, 2008. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ↑ "Questions and Answers: Extension of Optional Practical Training Program for Qualified Students". USCIS. 2012-04-25.

- ↑ "Extension of Post Completion Optional Practical Training (OPT) and F-1 Status for Eligible Students under the H-1B Cap-Gap Regulations". USCIS. 15 March 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

F-1 students who receive science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) degrees included on the STEM Designated Degree Program List, are employed by employers enrolled in E-Verify, and who have received an initial grant of post-completion OPT employment authorization related to such a degree, may apply for a 17-month extension of such authorization.

- ↑ "Questions and Answers: Extension of Optional Practical Training Program for Qualified Students". United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ↑ Thibodeau, Patrick (24 November 2014). "Federal judge refuses to dismiss suit challenging the OPT program, which President Obama is seeking to expand". Computer World. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ↑ "H-1B FOREIGN WORKERS Better Controls Needed to Help Employers and Protect Workers" (PDF). United States General Accounting Office. September 2000. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ Changes to the H-1B and L-1 Visa Application Fees, August 12, 2010

- ↑ Consolidated Natural Resources Act of 2008

- ↑ uscis.gov

- ↑ FAQ on affect of stimulus legislation on H-1B program, cglawaffiliates.x2cms.com/blog.

- 1 2 USCIS Interoffice Memorandum from Michael Aytes, Associate Director, Domestic Operations, to all Regional Directors and Service Center Directors, dated December 5, 2006

- ↑ "glossary". USCIS. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ↑ "Important Foreign Labor Certification H-1B Information".

- ↑ "Labor Condition Application for H-1B Nonimmigrants". United States Department of Labor. Nov 30, 1997. Archived from the original (PDF) on Aug 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Labor Condition Application for Nonimmigrant Workers, Form ETA 9035". United States Department of Labor. Nov 30, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on Aug 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Labor Condition Application for Nonimmigrant Workers ETA Form 9035 & 9035E". United States Department of Labor. Archived from the original (PDF) on Aug 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Labor Condition Application for H-1B Nonimmigrants" (PDF). ETA-9035. United States Department of Labor.

- ↑ "Nonimmigrant-Based Employment" (PDF). 27 Jun 2012.

- ↑ Bhatt, Sanjay (July 18, 2012). "Seattle ranks high in skilled foreign workers on H-1B visas". The Seattle Times.

- ↑ "Immigration Reforms Needed to Protect Skilled American Workers". judiciary.senate.gov. United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary. March 17, 2015. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ↑ "Immigration Reforms Needed to Protect Skilled American Workers" (video). c-span.org. C-Span. March 17, 2015. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ↑ Chuck Grassley (March 17, 2015). "Prepared Statement by Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa Chairman, Senate Judiciary Committee At a hearing entitled: "Immigration Reforms Needed to Protect Skilled American Workers"" (PDF). judiciary.senate.gov. Senate Judiciary Committee. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ↑ The Editorial Board of The New York Times (June 15, 2015). "Workers Betrayed by Visa Loopholes" (editorial). The New York Times. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- 1 2 How H-1B Visas Are Screwing Tech Workers, Mother Jones, February 22, 2013

- ↑ Moira Herbst (April 24, 2009). "H-1B Visa Law: Trying Again". Businessweek. Retrieved June 8, 2015.

- 1 2 Julia Preston (June 3, 2015). "Last Task After Layoff at Disney: Train Foreign Replacements". The New York Times. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

Former employees said many immigrants who arrived were younger technicians with limited data skills who did not speak English fluently and had to be instructed in the basics of the work

- ↑ Julia Preston (June 11, 2015). "Outsourcing Companies Under Scrutiny Over Visas for Technology Workers". The New York Times. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ↑ H-1B Is Just Another Gov't. Subsidy

- ↑ "Norm Matloff's H-1B Web Page: cheap labor, age discrimation, offshoring".

- ↑ ON THE NEED FOR REFORM OF THE H-1B NON-IMMIGRANT WORK VISA IN COMPUTER-RELATED OCCUPATIONS

- ↑ GAO Report on H-1B Foreign Workers

- 1 2 Editor. "Visa Window Opens; Scramble Is About to Begin". WSJ.

- ↑ S.1092: Hi-Tech Worker Relief Act of 2007. United States Congress via American Immigration Lawyers Association.

- ↑ S.1092: Hi-Tech Worker Relief Act of 2007. Thomas.gov. United States Library of Congress. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ↑ John Miano (June 2008). "H-1B Visa Numbers: No Relationship to Economic Need". Center for Immigration Studies. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- ↑ Numbers USA (2010). "There Is No Tech Worker Shortage". Numbers USA. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- 1 2 "H-1B Visa Harm Report". Hire Americans First. 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- ↑ "STEM Education Funding in the U.S. - Is More or Less Needed?".

- ↑ Ron Hira; Paula Stephan; et al. (27 July 2014). "Bill Gates' tech worker fantasy". USAtoday.

- ↑ https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Resources/Reports%20and%20Studies/H-1B/h-1B-characteristics-report-14.pdf

- ↑ Low Salaries for Low Skills: Wages and Skill Levels for H-1B Computer Workers, 2005 John M. Miano

- ↑ The Bottom of the Pay Scale: Wages for H-1B Computer Programmers John M. Miano

- ↑ Programmers Guild (2001). "How to Underpay H-1B Workers". Programmers Guild. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ↑ NumbersUSA (2010). "Numbers USA". NumbersUSA. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ↑ "H-1B Visa Ban for Bailed-out US Firms is Irrational: Montek". Outlook. February 18, 2009. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ↑ Ron Hira (Jan 12, 2008). "No, The Tech Skills Shortage Doesn't Exist". Information Week. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ↑ B. Lindsay Lowell, Georgetown University (October 2007). "Into the Eye of the Storm: Assessing the Evidence on Science and Engineering, Education, Quality, and Workforce Demand" (PDF). The Urban Institute. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ↑ VIVEK WADHWA; GARY GEREFFI; BEN RISSING; RYAN ONG (Spring 2007). "Where the Engineers Are". The Urban Institute. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ↑ Borjas, George (2009). "Immigration in High-Skill Labor Markets: The Impact of Foreign Students on the Earnings of Doctorates". In Freeman, Richard B.; Goroff, Daniel. Science and Engineering Careers in the United States: An Analysis of Markets and Employment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 131–161. ISBN 0-226-26189-1.

- ↑ "Understanding the Economic Impact of the H-1B Program on the U.S." (PDF).

- ↑ "H-1B Prevailing Wage Enforcement On The Rise – Millions In Back Wages And Fines Ordered", millerjohnson.com.

- ↑ United States General Accounting Office, H-1B Foreign Workers: Better Controls Needed to Help Employers and Protect Workers

- ↑ 8 USC 1182 (n)

- 1 2 Alice LaPlante (July 14, 2007). "To H-1B Or Not To H-1B?". InformationWeek. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ↑ Sun Accused of Worker Discrimination, San Francisco chronicle, June 25, 2002, online text

- ↑ Santiglia v. Sun Microsystems, Inc., ARB No. 03-076, ALJ No. 2003-LCA-2 (ARB July 29, 2005)

- ↑ "Where the two candidates stand on tech-related immigration". Computerworld. Jul 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Bernie Sanders vs Hillary Clinton on H-1B and Guestworker Visas". The Economic Populist. March 29, 2016.

- ↑ Grow, Brian (June 6, 2003). "Skilled Workers – or Indentured Servants?". BusinessWeek.

- ↑ "Foreign tech workers touchy subject in U.S. downturn". Reuters. February 19, 2009.

- ↑ U.S. Department of State visa bulletin

- ↑ "FLOOR STATEMENT: H-1B Visa Reform". Archived from the original on January 8, 2011. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ↑ Patrick Thibodeau (14 December 2009). "List of H-1B visa employers for 2009". Computerworld.

- ↑ Yeoh; et al. (2004). State/Nation/transnation: Perspectives on Transnationalism in the Asia-Pacific. Routledge. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-415-30279-1.

- ↑ "Technology".

- ↑ Southern California Edison IT workers 'beyond furious' over H-1B replacements, Computer World, February 4, 2015

- ↑

- ↑ Patrick Thibodeau (4 September 2015). "Older IT pros pushed aside by younger H-1B workers". Computerworld. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ↑ Chris Woodward. "Attorney: Disney discriminated against its workers". OneNewsNow. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ↑ http://www.uscis.gov/USCIS/Resources/Reports/uscis-annual-report-2008.pdf

- 1 2 3 "H-1B Benefit Fraud & Compliance Assessment" (PDF). USCIS. September 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ↑ Roy Mark (13 Feb 2009). "Feds Bust Nationwide H-1B Visa Scam". eWeek. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- ↑ Moira Herbst and Steve Hamm (October 1, 2009). "America's High-Tech Sweatshops". BusinessWeek. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ↑ Alba, Davey (4 Nov 2014). "INVESTIGATION REVEALS SILICON VALLEY'S ABUSE OF IMMIGRANT TECH WORKERS". Wired. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ↑ Matt Smith; Jennifer Golan; Adithya Sambamurthy; Stephen Stock; Julie Putnam; Amy Pyle; Sheela Kamath; Nikki Frick (27 Oct 2014). "Job brokers steal wages, entrap Indian tech workers in US". The Center for Investigative Reporting, together with NBC Bay Area. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ↑ "Are You Coming To The United States Temporarily to Work or Study?" (PDF). www.ciee.org. US Department of State. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ↑ Mexican and Canadian NAFTA Professional Worker

- 1 2 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers Report for Fiscal Year 2012

- 1 2 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers Report for Fiscal Year 2004

- 1 2 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers Report for Fiscal Year 2005

- 1 2 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers Report for Fiscal Year 2006

- 1 2 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers Report for Fiscal Year 2007

- 1 2 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers Report for Fiscal Year 2008

- 1 2 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers Report for Fiscal Year 2010

- 1 2 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers Report for Fiscal Year 2011

- 1 2 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers Report for Fiscal Year 2009

- 1 2 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers Report for Fiscal Year 2012

- 1 2 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers Report for Fiscal Year 2014

- ↑ "Non-immigrant visa statistics". United States Department of State. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- 1 2 Marianne Kolbasuk McGee (May 17, 2007). "Who Gets H-1B Visas? Check Out This List". InformationWeek. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- 1 2 Peter Elstrom (June 7, 2007). "Immigration: Google Makes Its Case". BusinessWeek. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ↑ Jacob Sapochnick; Patrick Thibodeau (2009). "List of H-1B visa employers for 2009". ComputerWorld, BusinessWeek. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- 1 2 Peter Elstrom (June 7, 2007). "Immigration: Who Gets Temp Work Visas?". BusinessWeek. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ↑ ComputerWorld, USCIS 2007

- ↑ Patrick Thibodeau (23 February 2009). "List of H-1B visa employers for 2008". Computerworld.

- ↑ Patrick Thibodeau (14 December 2009). "List of H-1B visa employers for 2009". Computerworld.

- ↑ Patrick Thibodeau (11 February 2011). "Top H-1B visa user of 2010: An Indian firm". Computerworld.

- ↑ Patrick Thibodeau; and Sharon Machlis (27 January 2012). "The top 10 H-1B visa users in the U.S.". Computerworld.

- ↑ Patrick Thibodeau; Sharon Machlis (14 February 2013). "The data shows: Top H-1B users are offshore outsourcers". Computerworld.

- ↑ Sharon Machlis; Patrick Thibodeau (1 April 2014). "Offshore firms took 50% of H-1B visas in 2013". Computerworld.

- ↑ HAEYOUN PARK (10 November 2015). "How Outsourcing Companies Are Gaming the Visa System". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ↑ Patrick Thibodeau; Sharon Machlis (30 July 2015). "Despite H-1B lottery, offshore firms dominate visa use". Infoworld. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ↑ Dawn Kawamoto (24 March 2016). "8 Biggest H-1B Employers In 2015". Information Week. pp. 1–9. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

References

- United States Citizenship and Immigration Service, "Characteristics of Specialty Occupation Workers (H-1B)", for FY 2004 and FY 2005, November 2006.

- "Microsoft Cuts 5,000 Jobs as Recession Curbs Growth (Update5)", Bloomberg, 22 Jan 2009 (Microsoft Lays off 5,000 even as they use 3,117 visas in 2006.)

- Bill Gates, Chairman of Microsoft, Testimony to the U.S. Senate Committee Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. Hearing "Strengthening American Competitiveness for the 21st Century". March 7, 2007

- Business Week, Immigration: Google Makes Its Case, 7 Jun 2007.

- Business Week, Who Gets Temp Work Visas? 7 Jun 2007 (Top 200 H-1B Visa Users Chart)

- Business Week, Immigration Fight: Tech vs. Tech, 25 May 2007.

- Business Week, Crackdown on Indian Outsourcing Firms, 15 May 2007.

- Dr. Norman Matloff, Debunking the Myth of a Desperate Software Labor Shortage, Testimony to the U.S. House Judiciary Committee, April 1998, updated December 2002

- Programmers Guild, PERM Fake Job Ads defraud Americans to secure green cards, Immigration attorneys from Cohen & Grigsby explains how they assist employers in running classified ads with the goal of NOT finding any qualified applicants.

- Lou Dobbs: Cook County Resolution against H-1B

- PRWeb, The Programmers Guild Calls on Congress to include U.S. Worker Protections in the Pending SKIL Bill H-1B Visa Legislation

- CNN, Lou Dobbs, Programmers Guild Interview & Transcript, August 26, 2005

- Congressional Record: ILLEGAL ALIENS TAKING AMERICAN JOBS, June 18, 2003 (House)

- Center for Immigration Studies, Backgrounder: The bottom of the pay scale, Wages for H-1B Computer Programmer's, John Milano, 2005.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), Report, EXPORT CONTROLS: Department of Commerce Controls over Transfers of Technology to Foreign Nationals Need Improvement

- Attestation Requirements of an H-1B Dependent Employer

External links for H-1B information

- The H-1B Visa Program: A Primer on the Program and Its Impact on Jobs, Wages, and the Economy

- Top H-1B Visa Sponsors by Industry, Occupation, Economic Sector and Locations

- U.S. Department of State information on H-1B visa

- U.S. GAO Report on H-1B Problems, PDF format

- H-1B Quota Updates from USCIS

Other links

- Pittsburgh law firm's immigration video sparks an Internet firestorm, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 22, 2007

- "Lawmakers Request Investigation Into YouTube Video" Sen. Chuck Grassley and Rep. Lamar Smith ask the Labor Department to look into a video they say documents H-1B abuse by companies. Information Week, June 21, 2007

- H1B Visa Description, Advantages & Requirements

- Oct. 2007 study by Georgetown University – The study raises questions about the use of test scores by visa-worker-seeking technology companies to claim that American citizens are not qualified.

- "America's New Immigrant Entrepreneurs" – A Duke University Study

- "H1B Jobs: Filling the Skills Gap" - An American Institute for Economic Research Issue Brief