Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut, Hadhramout, Hadramawt or Ḥaḍramūt (Arabic: حضرموت Ḥaḍramawt) is a region on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula. The name is officially retained in Hadhramaut Governorate of the Republic of Yemen. The people of Hadhramaut are called Hadhrami and speak Hadhrami Arabic.

Etymology

The origin of the name "Ḥaḍramawt" is not exactly known, and there are numerous competing hypotheses about its meaning.

The most common folk etymology is that the region's name means "death has come," from /ḥaḍara/ (Arabic for "has come") and /mawt/ ("death"), though there are multiple explanations for how it came to be known as such. One explanation is that this is a nickname of 'Amar ibn Qaḥṭān, a legendary invader of the region, whose battles always left many dead. Another theory is that after the destruction of Thamūd, the Islamic prophet Ṣāliḥ relocated himself and about 4,000 of his followers to the region and it was there that he died, thus lending the region its morbid name "death has come."

Ḥaḍramawt is also identified with Biblical Hazarmawet (Genesis 10:26[1] and 1 Chronicles 1:20[2]). There, it is the name of a son of Joktan (who is also identified with Qahtan), the ancestor of the South Arabian kingdoms. According to various Bible dictionaries, the name "Hazarmaveth" means "court of death," reflecting a meaning similar to the Arabic folk etymologies.

Scholarly theories of the name's origin are somewhat more varied, but none have gained general acceptance. Juris Zarins, rediscoverer of the city claimed to be the ancient Incense Route trade capital Ubar in Oman, suggested that the name may come from the Greek word ὕδρευματα, or enclosed (and often fortified) watering stations at wadis. In a Nova interview,[3] he described Ubar as

a kind of fortress/administration center set up to protect the water supply from raiding Bedouin tribes. Surrounding the site, as far as six miles away, were smaller villages, which served as small-scale encampments for the caravans. An interesting parallel to this are the fortified water holes in the Eastern Desert of Egypt from Roman times. There, they were called hydreumata.

Though it accurately describes the configuration of settlements in the Pre-Islamic Wadi Ḥaḍramawt, this explanation for the name is anachronistic and has gained no wider scholarly acceptance.

Already in the Pre-Islamic period, variations of the name are attested as early as the middle of the First Millennium BC. The names ḥḍrmt and ḥḍrmwt are found in texts of the Old South Arabian languages (Ḥaḍramitic, Minaic, Qatabanic, and Sabaic), though the second form is not found in any known Ḥaḍramitic inscriptions.[4] In either form, the word itself can be a toponym, a tribal name, or the name of the kingdom of Ḥaḍramawt. In the late Fourth or early Third Century BC, Theophrastus gives the name Άδρραμύτα,[5] a direct transcription of the Semitic name into Greek.

As Southern Arabia is the homeland of the South Semitic language subfamily, a Semitic origin for the name is highly likely. Kamal Salibi proposed an alternative etymology for the name which argues that the diphthong "aw" in the name is an incorrect vocalization.[6] He notes that "-ūt" is a frequent ending for place names in the Ḥaḍramawt, and given that Ḥaḍramūt is the colloquial pronunciation of the name, and apparently also its ancient pronunciation, the correct reading of the name should be "place of ḥḍrm." He proposes, then, that the name means "the green place," which is apt for its well-watered wadis whose lushness contrasts with the surrounding high desert plateau.

Geography

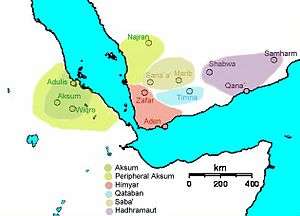

Narrowly, Hadhramaut refers to the historical Qu'aiti and Kathiri sultanates , which were in the Aden Protectorate overseen by the British Resident at Aden until their abolition upon the independence of South Yemen in 1967. The current governorate of Hadhramaut roughly incorporates the former territory of the two sultanates It consists of a narrow, arid coastal plain bounded by the steep escarpment of a broad plateau (al-Jawl, averaging 1,370 m (4,490 ft)), with a very sparse network of deeply sunk wadis (seasonal watercourses). The undefined northern edge of Hadhramaut slopes down to the desert Empty Quarter.

In a wider sense, Hadhramaut includes the territory of Mahra to the east all the way to the contemporary border with Oman.[7] This encompasses the current governorates of Hadramaut and Mahra in their entirety as well as parts of the Shabwah Governorate.

The Hadhramis live in densely built towns centered on traditional watering stations along the wadis. Hadhramis harvest crops of wheat and millet, tend date palm and coconut groves, and grow some coffee. On the plateau, Bedouins tend sheep and goats. Society is still highly tribal, with the old Seyyid aristocracy, descended from the Islamic prophet, Muhammad, traditionally educated and strict in their Islamic observance and highly respected in religious and secular affairs.

Hadhrami diaspora

Since the early 19th century, large-scale Hadhramaut migration has established sizable Hadhrami minorities all around the Indian Ocean,[8] in South Asia, Southeast Asia and East Africa including Hyderabad,Aurangabad (Now Included in Maharashtra State),[9][10] Bhatkal, Gangolli, Malabar, Sylhet, Java, Sumatra, Malacca, Sri Lanka, southern Philippines and Singapore.

In Hyderabad and Aurangabad, the community is known as Chaush and resides mostly in the neighborhood of Barkas.

In Gujarat, the Surrati people reign from Hadhramaut.

Several Indonesian ministers, including former Foreign Minister Ali Alatas and former Finance Minister Mari'e Muhammad are of Hadhrami descent, as is the former Prime Minister of East Timor, Mari Alkatiri.[11](2006).

Hadhramis have also settled in large numbers along the East African coast,[12] and two former ministers in Kenya, Shariff Nasser and Najib Balala, are of Hadhrami descent. Genetic evidence has linked the Lemba people, an African Jewish community of Zimbabwe and South Africa, to the people of the Hadramaut region.[13] Among the Hadramaut region there has been a historical Jewish population, suggesting both religious and ethnic continuity between Hadhramis and the Lemba.[14]

Modern history of the Wadi Hadhramaut

The Qu'aiti sultans ruled the vast majority of Hadramaut, under a loose British protectorate, the Aden Protectorate, from 1882 to 1967, when the Hadhramaut was annexed by South Yemen.

The Qu'aiti dynasty was founded by 'Umar bin Awadh al-Qu’aiti, a Yafa’i tribesman whose wealth and influence as hereditary Jemadar of the Nizam of Hyderabad's armed forces enabled him to establish the Qu'aiti dynasty in the latter half of the 19th century, winning British recognition of his paramount status in the region, in 1882. The British Government and the traditional and scholarly sultan Ali bin Salah signed a treaty in 1937 appointing the British government as "advisors" in Hadhramaut. The British exiled him to Aden in 1945, but the Protectorate lasted until 1967.

In 1967, the former British Colony of Aden and the former Aden Protectorate including Hadramaut became an independent Communist state, the People's Republic of South Yemen, later the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen. South Yemen was united with North Yemen in 1990 as the Republic of Yemen. See History of Yemen for recent history.

The capital and largest city of Hadhramaut is the port Al Mukalla. Al Mukalla had a 1994 population of 122,400 and a 2003 population of 174,700, while the port city of Ash Shihr has grown from 48,600 to 69,400 in the same time. One of the more historically important cities in the region is Tarim. An important locus of Islamic learning, it is estimated to contain the highest concentration of descendants of the Prophet Muhammad anywhere in the world.[15]

Economy

Historically, Hadhramaut was known for being a major producer of frankincense. They were mainly exporting it to Mumbai in the early 20th century.[16] The region has also produced senna and coconut.In the 21 Century, Hadhramout produces approximately (258.8 thousand) barrels per day One of the most oil fields is Al Maseelah in the strip (14), which was discovered in the year 1993, the Yemeni government is keen to develop its oil fields to increase oil production in order to increase national wealth in response to the requirements of economic and social development in the country , the fact that oil contributes to a rate ranging between (30-40)% of the value of GDP and captures more than 70% of the total state budget revenues and accounts for more than 90% of the value of the country's exports. [17]

See also

References

- ↑ Genesis 10:26

- ↑ 1 Chronicles 1:20

- ↑ "Lost City of Arabia" (NOVA online interview with Dr. Juris Zarins). PBS. September 1996.

- ↑ "General word list". DASI: Digital Archive for the Study of pre-islamic arabian Inscriptions. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ Theophrastus: Historia Plantarum. 9,4.

- ↑ Salibi, Kamal (1981). al-Qāḍī, ed. "Ḥaḍramūt: A Name with a Story". Studia Arabica et Islamica: Festschrift for Iḥsān ʿAbbās on His Sixtieth Birthday: 393–397.

- ↑ Richard N. Schofield, Gerald Henry Blake, Arabian Boundaries: Primary Documents, 1853–1957 Volume 22, Archive Editions, 1988, ISBN 1-85207-130-3, pg 220 ...should be made along the coast to the west as far as the DHOFAR-HADHRAMAUT frontier...

- ↑ Engseng Ho, The Graves of Tarim: Genealogy and Mobility across the Indian Ocean, University of California Press, 2006

- ↑ Omar Khalidi, The Arabs of Hadramawt in Hyderabad in Mediaeval Deccan History, eds Kulkarni, Naeem and de Souza, Popular Prakashan, Bombay, 1996

- ↑ Leif Manger, Hadramis in Hyderabad: From Winners to Losers, Asian Journal of Social Science, Volume 35, Numbers 4-5, 2007, pp. 405-433(29)

- ↑ Agence France-Presse

- ↑ Anne K. Bang, Sufis and Scholars of the Sea: Family Networks in East Africa, 1860-1925, Routledge, 2003

- ↑ Espar, David. "Tudor Parfitt's Remarkable Quest". www.pbs.org. PBS. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ Wahrman, Miryam Z. (1 January 2004). Brave New Judaism: When Science and Scripture Collide. UPNE. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-58465-032-4.

- ↑ Alexandroni, S. No Room at the Inn. New Statesman, October 2007

- ↑ Prothero, G.W. (1920). Arabia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 84.

- ↑ Prothero, G.W. (1920). Arabia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 85.

External links

- Architecture of Mud: documentary Film about the rapidly disappearing mud brick architecture in the Hadhramaut region.

- Nova special on Ubar, illustrating a hydreuma

- Book review of a biography of Qu'aiti sultan Alin din Salah

- Hadhrami migration in the 19th and 20th centuries

- Ba`alawi.com Ba'alawi.com | The Definitive Resource for Islam and the Alawiyyen Ancestry.