Halin graph

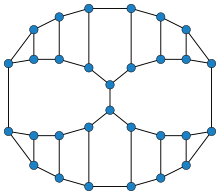

In graph theory, a Halin graph is a type of planar graph, constructed by connecting the leaves of a tree into a cycle. The tree must have at least four vertices, none of which has exactly two neighbors; it should be drawn in the plane so none of its edges cross (this is called planar embedding), and the cycle connects the leaves in their clockwise ordering in this embedding. Thus, the cycle forms the outer face of the Halin graph, with the tree inside it.[1]

Halin graphs are named after German mathematician Rudolf Halin, who studied them in 1971,[2] but the cubic Halin graphs had already been studied over a century earlier by Kirkman.[3] They are polyhedral graphs, and the polyhedra formed from them have been called roofless polyhedra or domes. Every Halin graph has a Hamiltonian cycle as well as cycles of almost all lengths up to their number of vertices. They can be recognized in linear time, and many computational problems can be solved more quickly on them than on other kinds of planar graphs.

Examples

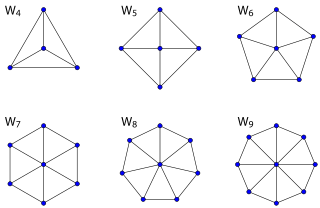

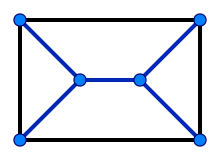

A star is a tree with exactly one internal vertex. Applying the Halin graph construction to a star produces a wheel graph, the graph of the (edges of) a pyramid. The graph of a triangular prism is also a Halin graph: it can be drawn so that one of its rectangular faces is the exterior cycle, and the remaining edges form a tree with four leaves, two interior vertices, and five edges.

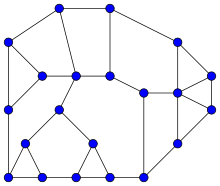

The Frucht graph, one of the two smallest cubic graphs with no nontrivial graph automorphisms, is also a Halin graph.

Properties

Every Halin graph is 3-connected, meaning that it is not possible to delete two vertices from it and disconnect the remaining vertices. It is edge-minimal 3-connected, meaning that if any one of its edges is removed, the remaining graph will no longer be 3-connected.[1] By Steinitz's theorem, as a 3-connected planar graph, it can be represented as the set of vertices and edges of a convex polyhedron; that is, it is a polyhedral graph. And, as with every polyhedral graph, its planar embedding is unique up to the choice of which of its faces is to be the outer face.[1]

Every Halin graph is a Hamiltonian graph, and every edge of the graph belongs to a Hamiltonian cycle. Moreover, any Halin graph remains Hamiltonian after deletion of any vertex.[4] Because every tree without vertices of degree 2 contains two leaves that share the same parent, every Halin graph contains a triangle. In particular, it is not possible for a Halin graph to be a triangle-free graph nor a bipartite graph.

More strongly, every Halin graph is almost pancyclic, in the sense that it has cycles of all lengths from 3 to n with the possible exception of a single even length. Moreover, any Halin graph remains almost pancyclic if a single edge is contracted, and every Halin graph without interior vertices of degree three is pancyclic.[5]

The weak dual of an embedded planar graph has vertices corresponding to bounded faces of the planar graph, and edges corresponding to adjacent faces. The weak dual of a Halin graph is always biconnected and outerplanar. This property may be used to characterize the Halin graphs: an embedded planar graph is a Halin graph, with the leaf cycle of the Halin graph as the outer face of the embedding, if and only if its weak dual is biconnected and outerplanar.[6]

The incidence chromatic number of a Halin graph G with maximum degree Δ(G) greater than four is Δ(G) + 1.[7] When Δ(G) = 3 or 4, the incidence chromatic number may be as large as 5 or 6 respectively.[8]

Computational complexity

It is possible to test whether a given n-vertex graph is a Halin graph in linear time, by finding a planar embedding of the graph (if one exists), and then testing whether there exists a face that has at least n/2 + 1 vertices, all of degree three. If so, there can be at most four such faces, and it is possible to check in linear time for each of them whether the rest of the graph forms a tree with the vertices of this face as its leaves. On the other hand, if no such face exists, then the graph is not Halin.[9] Alternatively, a graph withn vertices and m edges is Halin if and only if it is planar, 3-connected, and has a face whose number of vertices equals the circuit rank m − n + 1 of the graph, all of which can be checked in linear time.[6] Other methods for recognizing Halin graphs in linear time include the application of Courcelle's theorem, or a method based on graph rewriting, neither of which rely on knowing the planar embedding of the graph.[10]

Every Halin graph has treewidth = 3.[11] Therefore, many graph optimization problems that are NP-complete for arbitrary planar graphs, such as finding a maximum independent set, may be solved in linear time on Halin graphs using dynamic programming[12] or Courcelle's theorem, or in some cases (such as the construction of Hamiltonian cycles) by direct algorithms.[10] However, it is NP-complete to find the largest Halin subgraph of a given graph, to test whether there exists a Halin subgraph that includes all vertices of a given graph, or to test whether a given graph is a subgraph of a larger Halin graph.[13]

History

In 1971, Halin introduced the Halin graphs as a class of minimally 3-vertex-connected graphs: for every edge in the graph, the removal of that edge reduces the connectivity of the graph.[2] These graphs gained in significance with the discovery that many algorithmic problems that were computationally infeasible for arbitrary planar graphs could be solved efficiently on them.[4][6] This fact was later explained to be a consequence of their low treewidth, and of algorithmic meta-theorems like Courcelle's theorem that provide efficient solutions to these problems on any graph of low treewidth.[11][12]

Prior to Halin's work on these graphs, graph enumeration problems concerning the cubic Halin graphs were studied in 1856 by Thomas Kirkman[3] and in 1965 by Hans Rademacher.[14] Rademacher calls these graphs based polyhedra. He defines them as the cubic polyhedral graphs with f faces in which one of the faces has f − 1 sides. The graphs that fit this definition are exactly the cubic Halin graphs.

The Halin graphs are sometimes also called roofless polyhedra,[4] but, like "based polyhedra", this name may also refer to the cubic Halin graphs.[15] The convex polyhedra whose graphs are Halin graphs have also been called domes.[16]

References

- 1 2 3 Encyclopaedia of Mathematics, first Supplementary volume, 1988, ISBN 0-7923-4709-9, p. 281, article "Halin Graph", and references therein.

- 1 2 Halin, R. (1971), "Studies on minimally n-connected graphs", Combinatorial Mathematics and its Applications (Proc. Conf., Oxford, 1969), London: Academic Press, pp. 129–136, MR 0278980.

- 1 2 Kirkman, Th. P. (1856), "On the enumeration of x-edra having triedral summits and an (x − 1)-gonal base", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London: 399–411, doi:10.1098/rstl.1856.0018, JSTOR 108592.

- 1 2 3 Cornuéjols, G.; Naddef, D.; Pulleyblank, W. R. (1983), "Halin graphs and the travelling salesman problem", Mathematical Programming, 26 (3): 287–294, doi:10.1007/BF02591867.

- ↑ Skowrońska, Mirosława (1985), "The pancyclicity of Halin graphs and their exterior contractions", in Alspach, Brian R.; Godsil, Christopher D., Cycles in Graphs, Annals of Discrete Mathematics, 27, Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., pp. 179–194.

- 1 2 3 Sysło, Maciej M.; Proskurowski, Andrzej (1983), "On Halin graphs", Graph Theory: Proceedings of a Conference held in Lagów, Poland, February 10–13, 1981, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, 1018, Springer-Verlag, pp. 248–256, doi:10.1007/BFb0071635.

- ↑ Wang, Shu-Dong; Chen, Dong-Ling; Pang, Shan-Chen (2002), "The incidence coloring number of Halin graphs and outerplanar graphs", Discrete Mathematics, 256 (1-2): 397–405, doi:10.1016/S0012-365X(01)00302-8, MR 1927561.

- ↑ Shiu, W. C.; Sun, P. K. (2008), "Invalid proofs on incidence coloring", Discrete Mathematics, 308 (24): 6575–6580, doi:10.1016/j.disc.2007.11.030, MR 2466963.

- ↑ Fomin, Fedor V.; Thilikos, Dimitrios M. (2006), "A 3-approximation for the pathwidth of Halin graphs", Journal of Discrete Algorithms, 4 (4): 499–510, doi:10.1016/j.jda.2005.06.004, MR 2577677.

- 1 2 Eppstein, David (2016), "Simple recognition of Halin graphs and their generalizations", Journal of Graph Algorithms and Applications, 20 (2): 323–346, arXiv:1502.05334

, doi:10.7155/jgaa.00395.

, doi:10.7155/jgaa.00395. - 1 2 Bodlaender, Hans (1988), Planar graphs with bounded treewidth (PDF), Technical Report RUU-CS-88-14, Department of Computer Science, Utrecht University.

- 1 2 Bodlaender, Hans (1988), "Dynamic programming on graphs with bounded treewidth", Proceedings of the 15th International Colloquium on Automata, Languages and Programming, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 317, Springer-Verlag, pp. 105–118, doi:10.1007/3-540-19488-6_110, ISBN 978-3540194880.

- ↑ Horton, S. B.; Parker, R. Gary (1995), "On Halin subgraphs and supergraphs", Discrete Applied Mathematics, 56 (1): 19–35, doi:10.1016/0166-218X(93)E0131-H, MR 1311302.

- ↑ Rademacher, Hans (1965), "On the number of certain types of polyhedra", Illinois Journal of Mathematics, 9: 361–380, MR 0179682.

- ↑ Lovász, L.; Plummer, M. D. (1974), "On a family of planar bicritical graphs", Combinatorics (Proc. British Combinatorial Conf., Univ. Coll. Wales, Aberystwyth, 1973), London: Cambridge Univ. Press, pp. 103–107. London Math. Soc. Lecture Note Ser., No. 13, MR 0351915.

- ↑ Demaine, Erik D.; Demaine, Martin L.; Uehara, Ryuhei (2013), "Zipper unfolding of domes and prismoids", Proceedings of the 25th Canadian Conference on Computational Geometry (CCCG 2013), Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, August 8–10, 2013, pp. 43–48.

External links

- Halin graphs, Information System on Graph Class Inclusions.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Halin Graph". MathWorld.