Hammurabi

| Hammurabi | |

|---|---|

|

Hammurabi (standing), depicted as receiving his royal insignia from Shamash (or possibly Marduk). Hammurabi holds his hands over his mouth as a sign of prayer[1] (relief on the upper part of the stele of Hammurabi's code of laws). | |

| Born |

c. 1810 BC Babylon |

| Died |

1750 BC middle chronology (modern-day Jordan and Syria) (aged c. 60) Babylon |

| Known for | Code of Hammurabi |

| Title | King of Babylon |

| Term | 42 years; c. 1792 – 1750 BC (middle) |

| Predecessor | Sin-Muballit |

| Successor | Samsu-iluna |

| Religion | Babylonian religion |

| Children | Samsu-iluna |

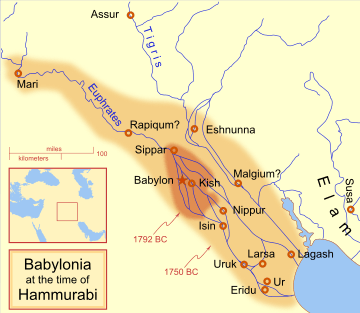

Hammurabi (c. 1810 BC - 1750 BC) was the sixth king of the First Babylonian Dynasty, reigning from 1792 BC to 1750 BC (according to the Middle Chronology). He was preceded by his father, Sin-Muballit, who abdicated due to failing health. He extended Babylon's control throughout Mesopotamia through military campaigns.[2] Hammurabi is known for the Code of Hammurabi, one of the earliest surviving codes of law in recorded history. The name Hammurabi derives from the Amorite term ʻAmmurāpi ("the kinsman is a healer"), itself from ʻAmmu ("paternal kinsman") and Rāpi ("healer").

Reign and conquests

Hammurabi was an Amorite First Dynasty king of the city-state of Babylon, and inherited the power from his father, Sin-Muballit, in c. 1792 BC.[4] Babylon was one of the many largely Amorite ruled city-states that dotted the central and southern Mesopotamian plains and waged war on each other for control of fertile agricultural land.[5] Though many cultures co-existed in Mesopotamia, Babylonian culture gained a degree of prominence among the literate classes throughout the Middle East under Hammurabi.[6] The kings who came before Hammurabi had founded a relatively minor City State in 1894 BC which controlled little territory outside of the city itself. Babylon was overshadowed by older, larger and more powerful kingdoms such as Elam, Assyria, Isin, Eshnunna and Larsa for a century or so after its founding. However his father Sin-Muballit had begun to consolidate rule of a small area of south central Mesopotamia under Babylonian hegemony and, by the time of his reign, had conquered the minor city-states of Borsippa, Kish, and Sippar.[6]

Thus Hammurabi ascended to the throne as the king of a minor kingdom in the midst of a complex geopolitical situation. The powerful kingdom of Eshnunna controlled the upper Tigris River while Larsa controlled the river delta. To the east of Mesopotamia lay the powerful kingdom of Elam which regularly invaded and forced tribute upon the small states of southern Mesopotamia. In northern Mesopotamia, the Assyrian king Shamshi-Adad I, who had already inherited centuries old Assyrian colonies in Asia Minor, had expanded his territory into the Levant and central Mesopotamia,[7] although his untimely death would somewhat fragment his empire.[8]

The first few decades of Hammurabi's reign were quite peaceful. Hammurabi used his power to undertake a series of public works, including heightening the city walls for defensive purposes, and expanding the temples.[9] In c. 1801 BC, the powerful kingdom of Elam, which straddled important trade routes across the Zagros Mountains, invaded the Mesopotamian plain.[10] With allies among the plain states, Elam attacked and destroyed the kingdom of Eshnunna, destroying a number of cities and imposing its rule on portions of the plain for the first time.[11] In order to consolidate its position, Elam tried to start a war between Hammurabi's Babylonian kingdom and the kingdom of Larsa.[12] Hammurabi and the king of Larsa made an alliance when they discovered this duplicity and were able to crush the Elamites, although Larsa did not contribute greatly to the military effort.[12] Angered by Larsa's failure to come to his aid, Hammurabi turned on that southern power, thus gaining control of the entirety of the lower Mesopotamian plain by c. 1763 BC.[13]

As Hammurabi was assisted during the war in the south by his allies from the north such as Yamhad and Mari, the absence of soldiers in the north led to unrest.[13] Continuing his expansion, Hammurabi turned his attention northward, quelling the unrest and soon after crushing Eshnunna.[14] Next the Babylonian armies conquered the remaining northern states, including Babylon's former ally Mari, although it is possible that the 'conquest' of Mari was a surrender without any actual conflict.[15][16][17]

Hammurabi entered into a protracted war with Ishme-Dagan I of Assyria for control of Mesopotamia, with both kings making alliances with minor states in order to gain the upper hand. Eventually Hammurabi prevailed, ousting Ishme-Dagan I just before his own death. Mut-Ashkur the new king of Assyria was forced to pay tribute to Hammurabi, however Babylon did not rule Assyria directly.

In just a few years, Hammurabi had succeeded in uniting all of Mesopotamia under his rule.[17] The Assyrian kingdom survived but was forced to pay tribute during his reign, and of the major city-states in the region, only Aleppo and Qatna to the west in the Levant maintained their independence.[17] However, one stele of Hammurabi has been found as far north as Diyarbekir, where he claims the title "King of the Amorites".[18]

Vast numbers of contract tablets, dated to the reigns of Hammurabi and his successors, have been discovered, as well as 55 of his own letters.[19] These letters give a glimpse into the daily trials of ruling an empire, from dealing with floods and mandating changes to a flawed calendar, to taking care of Babylon's massive herds of livestock.[20] Hammurabi died and passed the reins of the empire on to his son Samsu-iluna in c. 1750 BC, under whose rule the Babylonian empire began to quickly unravel.[21]

Code of laws

The Code of Hammurabi was inscribed on a stele and placed in a public place so that all could see it, although it is thought that few were literate. The stele was later plundered by the Elamites and removed to their capital, Susa; it was rediscovered there in 1901 in Iran and is now in the Louvre Museum in Paris. The code of Hammurabi contained 282 laws, written by scribes on 12 tablets. Unlike earlier laws, it was written in Akkadian, the daily language of Babylon, and could therefore be read by any literate person in the city.[22]

The structure of the code is very specific, with each offense receiving a specified punishment. The punishments tended to be very harsh by modern standards, with many offenses resulting in death, disfigurement, or the use of the "Eye for eye, tooth for tooth" (Lex Talionis "Law of Retaliation") philosophy.[23] The code is also one of the earliest examples of the idea of presumption of innocence, and it also suggests that the accused and accuser have the opportunity to provide evidence.[24] However, there is no provision for extenuating circumstances to alter the prescribed punishment.

A carving at the top of the stele portrays Hammurabi receiving the laws from the god Shamash or possibly Marduk,[25] and the preface states that Hammurabi was chosen by the gods of his people to bring the laws to them. Parallels between this narrative and the giving of laws by God in Jewish tradition to Moses and similarities between the two legal codes suggest a common ancestor in the Semitic background of the two. Fragments of previous law codes have been found.[26][27][Note 1][28][29] However David P. Wright argues that the Covenant Code of the Biblical Book of Exodus is 'directly, primarily, and throughout' based upon the Laws of Hammurabi.[30]

Similar codes of law were created in several nearby civilizations, including the earlier Mesopotamian examples of Ur-Nammu's code, Laws of Eshnunna, and Code of Lipit-Ishtar, and the later Hittite code of laws.[31]

Example laws in Hammurabi's code

- (Text taken from Harper's translation, readable on wikisource)

- § 8 – If any one steal cattle or sheep, or an ass, or a pig or a goat, if it belong to a god or to the court, the thief shall pay thirtyfold therefor; if they belonged to a freed man of the king he shall pay tenfold; if the thief has nothing with which to pay he shall be put to death.

- § 21 – If a man make a breach in a house, they shall put him to death in front of that breach and they shall thrust him therein.

- § 55 – If a man open his canal for irrigation and neglect it and the water carry away an adjacent field, he shall measure out grain on the basis of the adjacent fields.

- § 59 – If a man cut down a tree in a man's orchard, without the consent of the owner of the orchard, he shall pay one-half mina of silver.

- § 168 – If a man set his face to disinherit his son and say to the judges: "I will disinherit my son," the judges shall inquire into his antecedents, and if the son have not committed a crime sufficiently grave to cut him off from sonship, the father may not cut off his son from sonship.

- § 169 – If he have committed a crime against his father sufficiently grave to cut him off from sonship, they shall condone his first (offense). If he commit a crime a second time, the father may cut off his son from sonship.

- § 195 – If a son strike his father, they shall cut off his fingers.

- § 196–201 – If a man destroy the eye of another man, they shall destroy his eye. If one break a man's bone, they shall break his bone. If one destroy the eye of a freeman or break the bone of a freeman he shall pay one mana of silver. If one destroy the eye of a man's slave or break a bone of a man's slave he shall pay one-half his price. If a man knock out a tooth of a man of his own rank, they shall knock out his tooth. If one knock out a tooth of a freeman, he shall pay one-third mana of silver.

- § 218–219 – If a physician operate on a man for a severe wound with a bronze lancet and cause that man's death; or open an abscess (in the eye) of a man with a bronze lancet and destroy the man's eye, they shall cut off his fingers. If a physician operate on a slave of a freeman for a severe wound with a bronze lancet and cause his death, he shall restore a slave of equal value.

- § 229–232 – If a builder build a house for a man and do not make its construction firm, and the house which he has built collapse and cause the death of the owner of the house, that builder shall be put to death. If it cause the death of a son of the owner of the house, they shall put to death a son of that builder. If it cause the death of a slave of the owner of the house, he shall give the owner of the house a slave of equal value. If it destroy property, he shall restore whatever it destroyed, and because he did not make the house which he built firm and it collapsed, he shall rebuild the house which collapsed from his own property (i.e., at his own expense).

Legacy and depictions

During his reign Babylon usurped the position of "most holy city" in southern Mesopotamia from its predecessor, Nippur, for the final time (Babylon had also previously enjoyed this status under the Akkadians, before it was restored to Nippur in the "Sumerian renaissance").

Under the rule of Hammurabi's successor Samsu-iluna, the short-lived Babylonian Empire began to collapse. In northern Mesopotamia, both the Amorites and Babylonians were driven from Assyria by Puzur-Sin a native Akkadian-speaking ruler, circa 1740 BC. Around the same time, native Akkadian speakers threw off Amorite Babylonian rule in the far south of Mesopotamia, creating the Sealand Dynasty, in more or less the region of ancient Sumer. Hammurabi's ineffectual successors met with further defeats and loss of territory at the hands of Assyrian kings such as Adasi and Bel-ibni, as well as to the Sealand Dynasty to the south, Elam to the east, and to the Kassites from the northeast. Thus was Babylon quickly reduced to the small and minor state it had once been upon its founding.[32] The coup de grace for the Hammurabi's Amorite Dynasty occurred in 1595 BC, when Babylon was sacked and conquered by the powerful Hittite Empire, thereby ending all Amorite political presence in Mesopotamia.[33] However, the Indo-European-speaking Hittites did not remain, turning over Babylon to their Kassite allies, a people speaking a language isolate, from the Zagros mountains region. This Kassite Dynasty was to rule Babylon for over 400 years, adopting parts of the Babylonian culture, including Hammurabi's code of laws.

Because of Hammurabi's reputation as a lawgiver, his depiction can be found in several U.S. government buildings. Hammurabi is one of the 23 lawgivers depicted in marble bas-reliefs in the chamber of the U.S. House of Representatives in the United States Capitol.[34] A frieze by Adolph Weinman depicting the "great lawgivers of history", including Hammurabi, is on the south wall of the U.S. Supreme Court building.[35]

A theory current in the early part of the past century holds that Hammurabi was Amraphel, the King of Shinar in the Book of Genesis 14:1.[36][37]

See also

Further reading

- Finet, André (1973). Le trone et la rue en Mésopotamie: L'exaltation du roi et les techniques de l'opposition, in La voix de l'opposition en Mésopotamie. Bruxelles: Institut des Hautes Études de Belgique. OCLC 652257981.

- Jacobsen, Th. (1943). "Primitive democracy in Ancient Mesopotomia". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 2 (3): 159–172. doi:10.1086/370672.

- Finkelstein, J. J. (1966). "The Genealogy of the Hammurabi Dynasty". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 20 (3): 95–118. doi:10.2307/1359643.

- Hammurabi (1952). Driver, G.R.; Miles, John C., eds. The Babylonian Laws. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Leemans, W. F. (1950). The Old Babylonian Merchant: His Business and His Social Position. Leiden: Brill.

- Munn-Rankin, J. M. (1956). "Diplomacy in Western Asia in the Early Second Millennium BC". Iraq. 18 (1): 68–110. doi:10.2307/4199599.

- Pallis, S. A. (1956). The Antiquity of Iraq: A Handbook of Assyriology. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard.

- Richardson, M.E.J. (2000). Hammurabi's laws : text, translation and glossary. Sheffield: Sheffield Acad. Press. ISBN 1-84127-030-X.

- Saggs, H.W.F. (1988). The greatness that was Babylon : a survey of the ancient civilization of the Tigris-Euphrates Valley. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0-283-99623-4.

- Yoffee, Norman (1977). The economic role of the crown in the old Babylonian period. Malibu, CA: Undena Publications. ISBN 0-89003-021-9.

Notes

- ↑ Barton, a former professor of Semitic languages at the University of Pennsylvania, stated that while there are similarities between the two texts, a study of the entirety of both laws "convinces the student that the laws of the Old Testament are in no essential way dependent upon the Babylonian laws." He states that "such resemblances" arose from "a similarity of antecedents and of general intellectual outlook" between the two cultures, but that "the striking differences show that there was no direct borrowing."[27]

References

- ↑ Ancient Iraq by Georges Roux, Chapter 17 The Time of Confusion p. 266

- ↑ Roger B. Beck, Linda Black, Larry S. Krieger, Phillip C. Naylor & Dahia Ibo Shabaka (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X. OCLC 39762695.

- ↑ http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/royal-head-known-head-hammurabi

- ↑ Van De Mieroop 2005, p. 1

- ↑ Van De Mieroop 2005, pp. 1–2

- 1 2 Van De Mieroop 2005, p. 3

- ↑ Van De Mieroop 2005, pp. 3–4

- ↑ Van De Mieroop 2005, p. 16

- ↑ Arnold 2005, p. 43

- ↑ Van De Mieroop 2005, pp. 15–16

- ↑ Van De Mieroop 2005, p. 17

- 1 2 Van De Mieroop 2005, p. 18

- 1 2 Van De Mieroop 2005, p. 31

- ↑ Van De Mieroop 2005, pp. 40–41

- ↑ Van De Mieroop 2005, pp. 54–55

- ↑ Van De Mieroop 2005, pp. 64–65

- 1 2 3 Arnold 2005, p. 45

- ↑ Clay, Albert Tobias (1919). The Empire of the Amorites. Yale University Press. p. 97.

- ↑ Breasted 2003, p. 129

- ↑ Breasted 2003, pp. 129–130

- ↑ Arnold 2005, p. 42

- ↑ Breasted 2003, p. 141

- ↑ "Review: The Code of Hammurabi," J. Dyneley Prince, The American Journal of Theology Vol. 8, No. 3 (Jul., 1904), pp. 601–609 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3153895

- ↑ Victimology: Theories and Applications, Ann Wolbert Burgess, Albert R. Roberts, Cheryl Regehr, Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2009, p. 103

- ↑ Jaynes, Julian (1976). The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Houghton Mifflin Company Publishing. ISBN 0-395-20729-0.

- ↑ J. D. Douglas, Merrill C. Tenney, Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary (Zondervan, 2011), page 1323.

- 1 2 Barton, G.A: Archaeology and the Bible. University of Michigan Library, 2009, p.406.

- ↑ Unger, M.F.: Archaeology and the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing Co., 1954, p.156, 157

- ↑ Free, J.P.: Archaeology and Biblical History. Wheaton: Scripture Press, 1950, 1969, p. 121

- ↑ David P. Wright, Inventing God's Law: How the Covenant Code of the Bible Used and Revised the Laws of Hammurabi (Oxford University Press, 2009), page 3 and passim.

- ↑ Davies, W. W. (January 2003). Codes of Hammurabi and Moses. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-3124-6. OCLC 227972329.

- ↑ Georges Roux – Ancient Iraq

- ↑ DeBlois 1997, p. 19

- ↑ "Hammurabi". Architect of the Capitol. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ↑ "Courtroom Friezes" (PDF). Supreme Court of the United States. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 1, 2010. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ↑ http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/1440-amraphel

- ↑ http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Genesis%2014&version=NIV

Bibliography

- Arnold, Bill T. (2005). Who Were the Babylonians?. Brill Publishers. ISBN 90-04-13071-3. OCLC 225281611.

- Breasted, James Henry (2003). Ancient Time or a History of the Early World, Part 1. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-4946-3. OCLC 69651827.

- DeBlois, Lukas (1997). An Introduction to the Ancient World. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12773-4. OCLC 231710353.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc (2005). King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-2660-4. OCLC 255676990.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Hammurabi |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hammurabi. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Hammurabi |

- A Closer Look at the Code of Hammurabi (Louvre museum)

- Works by Hammurabi at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Hammurabi at Internet Archive

| Preceded by Sin-muballit |

Kings of Babylon | Succeeded by Samsu-iluna |