Handley Page Hastings

| Hastings | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hastings TG503 in flight in June 1977 | |

| Role | Transport aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Handley Page |

| First flight | 7 May 1946 |

| Introduction | September 1948 |

| Retired | 1977 (RAF) |

| Primary users | RAF RNZAF |

| Produced | 1947 – 1952 |

| Number built | 151 |

| Variants | Handley Page Hermes |

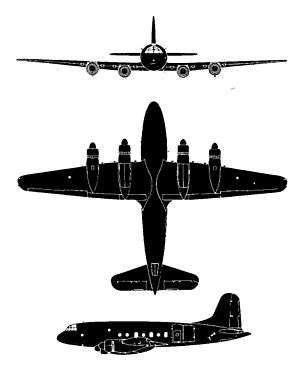

The Handley Page H.P.67 Hastings was a British troop-carrier and freight transport aircraft designed and built by the Handley Page Aircraft Company for the Royal Air Force. At the time, it was the largest transport plane ever designed for the RAF, and it replaced the Avro York as the standard long-range transport.

Design and development

Handley Page's answer to meet Air Staff Specification C.3/44 for a long-range general purpose transport was the H.P.67.[1] It was an all-metal low-wing cantilever monoplane with a conventional tail unit. It had all-metal tapering dihedral wings, which had been designed for the abandoned HP.66 bomber development of the Handley Page Halifax and a circular fuselage suitable for pressurisation up to 5.5 psi (38 kPa). It had a retractable undercarriage and tailwheel. The Hastings was powered by four wing-mounted Bristol Hercules 101 sleeve valve radial engines. In service, the aircraft was operated by a crew of five and could accommodate either 30 paratroopers, 32 stretchers and 28 sitting casualties, or 50 fully equipped troops.

A civilian version of the Hastings was developed as the Handley Page Hermes. The Hermes prototypes were given priority over the Hastings but that programme was put on hold after the prototype crashed on its first flight on 2 December 1945 and the company concentrated on the military Hastings variant.[2] The first of two Hastings prototypes (TE580) flew at RAF Wittering on 7 May 1946.[3] Tests showed that the aircraft was laterally unstable and that it had poor stall warning capabilities. The prototypes and first few production aircraft were subject to a series of urgent modifications and testing to resolve these problems. A temporary solution was found by modifying the tailplane with 15° of dihedral, while being fitted with synthetic stall warning.[4] This allowed the first production aircraft (Hastings C1) to enter service in October 1948.

The RAF initially ordered 100 Hastings C1s but the last six were built as weather reconnaissance versions as the Hastings Met. Mk 1, and seven other aircraft were converted to this standard. Eight C1 aircraft were later converted to Hastings T5 trainers which were used for training the V bomber crews, three at a time.

While tail modifications introduced to the C1 allowed it to enter service, a more definitive solution was the fitting of an extended-span tailplane, which was mounted lower on the fuselage. These changes, together with the fitting of additional fuel tanks in the outer wing, resulted in the C Mk 2,[5] while a further modified VIP transport, fitted with yet more fuel capacity to give a longer range became the C Mk 4.[6]

A total of 147 aircraft were built for the Royal Air Force and four for the Royal New Zealand Air Force, a total of 151.

Operational history

The Hastings was rushed into service because of the Berlin Airlift, with No. 47 Squadron replacing its Halifax A Mk 9s with Hastings in September–October 1948, flying its first sortie to Berlin on 11 November 1948. The Hastings fleet was mainly used to carry coal, with two further squadrons, 297 and 53 joining the airlift before its end.[7] A Hastings made the last sortie of the airlift on 6 October 1949,[8] the 32 Hastings deployed delivering 55,000 tons (49,900 tonnes) of supplies for the loss of two aircraft.[7]

One hundred Hastings C.Mk 1 and 41 Hastings C.Mk 2 were built, and they served both on Transport Command's long-range routes and as a tactical transport until well after the arrival of the Bristol Britannia in 1959. An example of the latter use was during the Suez Crisis when Hastings of 70, 99 and 511 Squadrons dropped paratroopers on El Gamil airfield.[9]

Hastings continued to provide transport support to British military operations around the globe through the 1950s and 60s, including dropping supplies to troops opposing Indonesian forces in Malaysia during the Indonesian Confrontation.[10]

The Hastings was retired from Royal Air Force Transport Command in early 1968 when it was replaced by the Lockheed Hercules.[11] The Met Mk.1 weather reconnaissance aircraft were used by No. 202 Squadron RAF at RAF Aldergrove, Northern Ireland from 1950 until the Squadron was disbanded on 31 July 1964, being made obsolete by weather satellites.[12] The Hastings T.Mk 5 remained in service as radar trainers well into the 1970s, even being used for reconnaissance purposes during the Cod War in the winter of 1975—76, finally being retired on 30 June 1977.[13]

Hastings were also operated in New Zealand, where the Royal New Zealand Air Force's 40 Squadron flew the type until replaced by C130 Hercules in 1965. Four Hastings C.Mk 3 transport aircraft were built and supplied to the RNZAF. One crashed at RAAF Base Darwin and caused considerable damage to the city's water main, its railway and the road into the city. The other three were broken up at RNZAF Base Ohakea. During the period that the engines were having problems with their sleeve valves (lubricating oil difficulties) RNZAF personnel joked that the Hastings was the best three-engined aircraft in the world.

Variants

- HP.67 Hastings

- Prototype, two built.

- HP.67 Hastings C1

- Production aircraft with four Bristol Hercules 101 engines, 94 built all later converted to C1A and T5.

- HP. 67 Hastings C1A

- C1 rebuilt to C2 standard

- HP.67 Hastings Met.1

- Weather reconnaissance version for Coastal Command, six built.

- HP.67 Hastings C2

- Improved version with larger-area tailplane mounted lower on fuselage, increased fuel capacity and powered by Bristol Hercules 106 engines, 43 built and C1s were modified to this standard as C1As.

- HP.95 Hastings C3

- Transport aircraft for the RNZAF, similar to C2 but had Bristol Hercules 737 engines, four built.

- HP.94 Hastings C4

- VIP transport version for four VIPs and staff, four built.

- HP.67 Hastings T5

- Eight C1s converted for RAF Bomber Command with ventral radome to train V bomber crews on the Navigation Bombing System (NBS).

Operators

- Royal Air Force.

- No. 24 Squadron RAF

- No. 36 Squadron RAF

- No. 47 Squadron RAF

- No. 48 Squadron RAF

- No. 51 Squadron RAF

- No. 53 Squadron RAF

- No. 59 Squadron RAF

- No. 70 Squadron RAF

- No. 97 Squadron RAF

- No. 99 Squadron RAF

- No. 114 Squadron RAF

- No. 115 Squadron RAF

- No. 116 Squadron RAF

- No. 151 Squadron RAF

- No. 202 Squadron RAF

- No. 242 Squadron RAF

- No. 297 Squadron RAF

- No. 511 Squadron RAF

- Far East Communications Squadron RAF

Survivors

Four Hastings are preserved in the UK and Germany:

- TG503 (T5) on display at the Alliiertenmuseum (Allied Museum), Berlin, Germany.

- TG511 (T5) on display at the RAF Museum Cosford, England.

- TG517 (T5) on display at the Newark Air Museum, Newark, England.

- TG528 (C1A) on display at the Imperial War Museum, Duxford, England.

- NZ5801 (C.3) 1952. Nose/Cockpit section only of RNZAF Military Transport is preserved at Auckland New Zealand's Museum of Transport and Technology along with engines, props and an undercarriage assembly, which is functional for display purposes.

Accidents and incidents

- 16 July 1949—Hastings TG611 lost control during takeoff at Berlin-Tegel Airport and dived into the ground due to incorrect tail trim; all five crew died.[14]

- 26 September—1949 Hastings TG499 lost the belly pannier, which hit the tail causing the aircraft to crash; all three crew died.[15]

- 20 December 1950—Hastings TG574 lost a propeller in flight, which hit the fuselage killing the co-pilot. The aircraft diverted to Benina, Libya and the aircraft flipped onto its back during landing. A total of five out of the seven crew were killed but the 27 passengers (all "slip" crews returning) survived.[16]

- 19 March 1951—Hastings WD478 stalled on takeoff at RAF Strubby; three crew died.[17]

- 16 September 1952—Hastings WD492 had a whiteout and crashed at Northice, Greenland. Three servicemen were injured during the incident but all the crew were safely recovered by USAF Rescue at Thule.[18]

- 12 January 1953—Hastings C1 TG602 crashed after takeoff when both elevator and the tailplane broke away; all five crew and four passengers died.[19]

- 22 June 1953—Hastings WJ335 stalled and crashed on takeoff at RAF Abingdon. The elevator control locks had been left engaged. All six crew died.[20]

- 23 July 1953—Hastings TG564 crashed on landing at Kai Tak with one fatality on the ground and the aircraft completely burnt out. Flight was outward bound for a casualty evacuation operation from Korea to the United Kingdom.[21]

- 2 March 1955—Hastings WD484 stalled and crashed on takeoff at RAF Boscombe Down due to the elevator controls being locked; all four crew died.[22]

- 9 September 1955—Hastings NZ5804 lost power on three engines due to multiple birdstrike and crashed just after takeoff from Darwin, Australia. 25 crew and passengers survived.

- 13 September 1955—Hastings TG584 lost control attempting to overshoot at RAF Dishforth and crashed; five died.

- 9 April 1956—Hastings WD483 undercarriage collapsed on landing and crashed at landing. No fatalities.

- 29 May 1959—Hastings TG522 stalled and crashed on approach to Khartoum Airport, Sudan, after engine failure. All five crew died, 25 passengers survived.[23]

- 1 March 1960—Hastings TG579 crash-landed in the sea 1.5 miles East of Gan, Maldives in a violent tropical storm. All six crew and 14 passengers survived[24]

- 29 May 1961—Hastings WD497 stalled and crashed in Singapore after an engine lost power; 13 died.[25]

- 10 October 1961—Hastings WD498 stalled and crashed on takeoff from RAF El Adem, Libya after the pilot's seat slid back. Seventeen of the 37 occupants died.[26]

- 17 December 1963—Hastings C1A TG610 engine failure during 'roller' landing at Thorney Island, Sussex. Aircraft ran into, and destroyed, a radio servicing building, killing one of the occupants and injuring four. The crew was uninjured.

- 6 July 1965 -- Hastings C1A TG577, departing from RAF Abingdon on a parachute drop, crashed at Little Baldon, Oxfordshire, with the loss of 41 lives. The cause was metal fatigue of two of the elevator bolts.[27]

- 4 May 1966—Hastings TG575 was written off when the undercarriage collapsed landing at El Adem, Libya.[28]

Specifications (Hastings C.2)

Data from Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1951–52[29]

General characteristics

- Crew: five (pilot, co-pilot, radio-operator, navigator and flight engineer)

- Capacity:

- 50 troops or

- 35 paratroops or

- 32 stretchers and 29 sitting wounded

- 20,311 lb (9,213 kg) maximum payload

- Length: 81 ft 8 in (24.89 m)

- Wingspan: 113 ft 0 in (34.44 m)

- Height: 22 ft 6 in (6.86 m)

- Wing area: 1,408 sq ft (130.8 m2)

- Aspect ratio: 9.08:1

- Airfoil: NACA 23021 at root, NACA 23007 at tip

- Empty weight: 48,472 lb (21,987 kg) (equipped, freighter)

- Max takeoff weight: 80,000 lb (36,287 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 3,172 imp gal (14,420 l; 3,809 US gal)

- Powerplant: 4 × Bristol Hercules 106 14-cyliner two-row air-cooled radial engines, 1,675 hp (1,249 kW) each

- Propellers: 4-bladed de Havilland constant speed, 13 ft 0 in (3.96 m) diameter

Performance

- Maximum speed: 348 mph (560 km/h; 302 kn) at 22,200 ft (6,800 m)

- Cruise speed: 291 mph (253 kn; 468 km/h) at 15,200 ft (4,600 m) (weak mixture)

- Range: 1,690 mi (1,469 nmi; 2,720 km) (maximum payload), 4,250 mi (3,690 nmi; 6,840 km) (maximum fuel, 7,400 lb (3,400 kg) payload)

- Service ceiling: 26,500 ft (8,077 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,030 ft/min (5.2 m/s)

- Time to altitude: 26 minutes to 26,000 ft (7,900 m)

- Take-off run to 50 ft (15 m): 1,775 yd (5,325 ft; 1,623 m)

- Landing run from 50 ft (15 m): 1,430 yd (4,290 ft; 1,310 m)

See also

- Related development

- Related lists

References

Notes

- ↑ Barnes 1976, p.435.

- ↑ Barnes 1976, p.437.

- ↑ Barnes 1976, p.440.

- ↑ Jackson 1989, p3.

- ↑ Jackson 1989, pp. 5—6.

- ↑ Jackson 1989, p.7.

- 1 2 Jackson 1989, pp.4—5.

- ↑ Thetford 1957, p.262.

- ↑ Jackson 1989, p.49.

- ↑ Jackson 1989, pp. 50—51.

- ↑ Jackson 1989, p.51

- ↑ Jackson 1989, pp. 49—50.

- ↑ Jackson 1989, p.52.

- ↑ TG611

- ↑ TG499

- ↑ TG574

- ↑ WD478

- ↑ Wilson, Keith (2015). RAF in camera, 1950s. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. p. 89. ISBN 9781473827950.

- ↑ TG602

- ↑ WJ335

- ↑

- ↑ WD484

- ↑ TG522

- ↑ Cooper, John. "Splashdown on the Equator". Britain's Small Wars. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ↑ WD497

- ↑ WD498

- ↑ TG577

- ↑ TG575

- ↑ Bridgman 1951, pp. 59c–60c.

Bibliography

- Barnes, C. H. Handley Page Aircraft Since 1907. London: Putnam, 1976. ISBN 0-370-00030-7.

- Barnes, C. H. Handley Page Aircraft Since 1907. London: Putnam & Company, Ltd., 1987.

- Bridgman, Leonard. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1951–52. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Company, Ltd, 1951.

- Clayton, Donald C. Handley Page, an Aircraft Album. Shepperton, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan Ltd., 1969. ISBN 0-7110-0094-8.

- Jackson, Paul. "The Hastings...Last of a Transport Line". Air Enthusiast. Issue Forty, September–December 1989. Bromley, Kent:Tri-Service Press. pp. 1–7,47—52.

- Hall, Alan W. Handley Page Hastings (Warpaint Series no.62). Bletchley, UK: Warpaint Books, 2007.

- Senior, Tim. Hastings, Including a Brief History of the Hermes - Handley Page's Post-War Transport Aircraft. Stamford, Lincs: Dalrymple & Verdun, 2008.

- Thetford, Owen. Aircraft of the Royal Air Force 1918-57. London: Putnam, First edition 1957.

- The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft (Part Work 1982-1985). Orbis Publishing.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Handley Page Hastings. |

- Berlin's Alliierten Museum, or Allied Museum, where a Hastings which served on the Berlin Airlift is preserved.

- The history of all the Handley Page Hastings Serial Numbers