Harike Wetland

| Harike Wetland and Harike Lake | |

|---|---|

Harike | |

| Location | Punjab |

| Coordinates | 31°10′N 75°12′E / 31.17°N 75.20°ECoordinates: 31°10′N 75°12′E / 31.17°N 75.20°E |

| Type | Freshwater |

| Primary inflows | Beas and Sutlej Rivers |

| Basin countries | India |

| Surface area | 4,100 hectares (10,000 acres) |

| Max. depth | 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) |

| Surface elevation | 210 metres (690 ft) |

| Islands | Thirty three islands |

| Settlements | Harike |

| Designated | 23 March 1990 |

Harike Wetland also known as "Hari-ke-Pattan", with the Harike Lake in the deeper part of it, is the largest wetland in northern India in the border of Tarn Taran Sahib district and Ferozepur district [1] of the Punjab state in India.

The wetland and the lake were formed by constructing the headworks across the Sutlej river, in 1953. The headworks is located downstream of the confluence of the Beas and Sutlej rivers. The rich biodiversity of the wetland which plays a vital role in maintaining the precious hydrological balance in the catchment with its vast concentration of migratory fauna of waterfowls including a number of globally threatened species (stated to be next only to the Keoladeo National Park near Bharatpur) has been responsible for the recognition accorded to this wetland in 1990, by the Ramsar Convention, as one of the Ramasar sites in India, for conservation, development and preservation of the ecosystem.:[2][3][4]

This man-made, riverine, lacustrine wetland spreads into the three districts of Tarn Taran Sahib, Ferozepur and Kapurthala in Punjab and covers an area of 4100 ha. Conservation of this Wetland has been given due importance, since 1987–88, both by the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India and the Punjab State Government (through its several agencies), and over the years several studies and management programmes have been implemented.[5]

Access

Harike or Hari-ke-Pattan as it is popularly called, is the nearest town to the wetland is Makhu(Ferozepur) Railway Station and Bus Stand is situated 10 km south of the Harike town, which connects to Ferozpur, Faridkot and Bhatinda by the National Highway.[6]

Hydrology and engineering aspects

Monsoon climate dominates the catchment draining into the wetland. The headworks built on the Sutlej River downstream of its confluence with Beas River and the reservoir created, which form the Harike lake and the enlarged wetland, is a purposeful project, which acts as the Headworks for irrigation and drinking water supplies, through the Ferozepur, Rajasthan and Makku feeder canals with total carrying capacity of 29,000 cubic feet per second (820 m3/s), to supply to the command areas located in the states of Punjab and Rajasthan. The grand Indira Gandhi Canal in Rajasthan is fed from this source. The lake is triangular in shape, with its apex in the west, bounded by a bund called the Dhussi Bund forming one side, a canal in the second and a major road on the third. The periphery of the lake is surrounded by agricultural land and the wetland is reported to be rich in ground water resources.[2][5]

Water quality

The Punjab State Council for Science & Technology has reported that the water quality of the lake is mostly of ‘A’ Class as per the designated best use criteria even though large volumes of polluted water discharge into the wetland from industries and urban centres.[5]

Biodiversity

The rich biodiversity of the wetland, with several species of birds, species of turtles, species of snakes, taxa of amphibians, taxa of fishes and taxa of invertebrates, is reportedly unique.[4][5]

Bird sanctuary

The wetland was declared a bird sanctuary in 1982 and named as Harike Pattan Bird Sanctuary with an extended area of 8600 ha.[7] Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) carried out research and a bird ringing programme during the period 1980–85.[3] An Ornithological field laboratory was proposed to be established by BNHS.[5]

200 species of birds visit the wetland during winter season of which some of the well known species (some are pictured in the gallery) are the cotton pygmy goose (Nettapus coromandelianus), tufted duck (Aythya fuligula), yellow-crowned woodpecker (Dendrocopos mahrattensis), yellow-eyed pigeon (Columba eversmanni), water cock (Gallicrex cinerea), Pallas's gull (Ichthyaetus ichthyaetus), brown-headed gull (Chroicocephalus brunnicephalus), black-headed gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus), yellow-footed gull (Larus michahellis), Indian skimmer (Rynchops albicollis), white-winged tern (Chlidonias leucopterus), white-rumped vulture (Gyps bengalensis), hen harrier (Circus cyaneus), Eurasian tree sparrow (Passer montanus), hawk (subfamily Accipitrinae), Eurasian hobby (Falco subbuteo), horned grebe (Podiceps auritus), black-necked grebe (Podiceps nigricollis), great crested grebe (Podiceps cristatus), white-browed fantail (Rhipidura aureola), brown shrike (Lanius cristatus), common woodshrike (Tephrodornis pondicerianus), white-tailed stonechat (Saxicola leucurus), white-crowned penduline tit (Remiz coronatus), rufous-vented prinia (Prinia burnesii), striated grassbird (Megalurus palustris), Cetti's warbler (Cettia cetti), sulphur-bellied warbler (Phylloscopus griseolus) and diving duck.[7]

Vegetation

The wetland’s rich floating vegetation comprises the following:[2]

- Eichhornia crassipes dominates in 50% area

- Azolla sp, is sparsely seen in open water areas.

- Nelumbo nucifera, the Lotus, the prominent rooted floating vegetation.

- Ipomoea aquatica, at the lake periphery in the shallower region

- Najas, Hydrilla, Ceratophyllum, Potamogeton, Vallisneria (eelgrass, tape grass vallis) and Charales are the species of Submerged vegetation

- Typha sp. Is the dominant emergent marsh vegetation

- Tiny floating islets are formed by Eichhornia crassipes and other grass species in the mud and root zone all over the wetland

Dalbergia sissoo, Acacia nilotica, Zizyphus sp, Ficus sp, alien Prosopis juliflora in large clumps and other trees are planted along the embankment. The State Wildlife Department has constructed earthen mounds in the marsh area with trees planted on it to increase nesting sites for the birds.

Aqua fauna

Endangered Testudines Turtle and Smooth Indian Otter or Smooth-coated Otter, listed in the IUCN (The International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) Redlist of Threatened Animals, are found in the wetland.[7]

26 species of fish are recorded which include Rohu, Catla, Puntius, Cirrhina, Channa, Mystus, Chitala chitala, Cyprinus, and Ambassis ranga.[4]

Invertebrates recorded are: Molluscs (39 & 4 taxa), Insects (6 & 32 taxa), Crustaceans (27 taxa), Annelids (7 taxa), Nematodes (7 & 4 taxa), Rotifers (59 & 13 taxa), and Protozoans (5 & 21 taxa).[4]

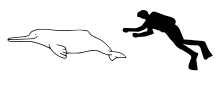

Indus dolphins

The Indus dolphin (Platanista gangetica minor) supposed to have become extinct in India after 1930, but largely found in the Indus river system in Pakistan, was recently sighted in the Beas River in Harike wetland area. This aquatic mammal classified as a critically endangered species in the Red Data Book of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources is considered a significant find. The dolphins were discovered by Basanta Rajkumar, IFS who was the officer in charge of the area while touring the area on a motorboat on the morning of December 14, 2007. Freshwater dolphin conservationist of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF)-India team, who were called in to help in surveying the area after the discovery, sighted a family of half a dozen dolphins at two different places along the 25-km stretch upstream of the Beas and thus confirmed the veracity of the claim made by the forest officials of the State govt. of finding the Indus dolphin in the wetland area. An authority on freshwater dolphins with the endangered species management wing of the Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun has also confirmed this finding. Discovering it in the year 2007, which was declared by the United Nations as Dolphin Year, was considered a special event. However, in the same Beas River, about 140 km downstream of the Harike Barrage in Pakistan territory, Indus dolphins are commonly found.[8]

Gharials

The Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) was once found in great numbers in the Indus river system before its population dwindled and it is now classified as Critically Endangered in the International Union for Conservation of Nature's (IUCN) Red List of Endangered Species.[9] The Punjab Government is now planning to release 10 gharials in the Harike Wetlands as the first step to increase their numbers and to attract more tourists.[10]

Wetland degradation

The wetland which is in existence since 1953 underwent changes over the years because of several factors, some of which are:[2][5][11]

- Encroachments on the wetland habitat for intensive agriculture with resultant effluents of agricultural chemicals and also controversial encroachments.

- Utilization of surface and ground waters for irrigation

- Effluent discharge of untreated waste from towns and villages from industrial, urban and agricultural activities into the rivers which feed the wetland resulting in extensive weed growth (Water Hyacinth) in the wetland (polluted water discharged was reported to be about 700 Million Liters per day (mld)

- The profuse growth of water hyacinth had covered 80 per cent of the open water surface resulting in the 33 islands getting enclosed.

- Soil erosion and siltation due to deforestation of the fragile lower Shivalik hills which form the catchment of the wetland

- Illegal fishing and poaching in spite of the Wildlife (Protection) Act.

- Indiscriminate grazing in the catchments resulting in damage to the wetland ecology

- A remote sensing study of the Wetland area coupled with the analysis of rainfall, discharge and ground water level showed that the flow pattern had diminished and the size of wetland area had reduced by about 30%, over a 13 years study period.[12]

- The ecological crisis had reached such a stage that environmentalists estimated lifespan of the wetland to be discreasing.

Restoration measures

The gravity of the degraded status of the wetland has been addressed for implementing several restoration measures by a plethora of organizations/agencies/research institutions of the central and state governments and also the Indian Army Units located in the area. The measures undertaken to conserve the wetland have covered the following actions.

The Chief Minister of the State of Punjab instituted, in 1998, the Harike Wetland Conservation Mission to:[3]

a) To prepare a Master Plan for the integrated conservation and development of the Harike wetland;

b) To undertake specific projects and programmes for the conservation of the ecosystem of the Harike region;

c) To regulate, screen and monitor all development activities which have a bearing on the Harike wetland ecosystem;

d) To evaluate all plans and proposals of all departments of the Government which concern the future of Harike

- The menace of water hyacinth was addressed by the Indian Army (Western Command, Vajra Corps.) in the year 2000, in a joint effort initiated by the Chief Minister of the State. Under the Pilot Project named “Sahyog” the Army adopted several innovative mechanical system of weed removal. The Army General reporting on the progress of the works stated:

- The Punjab State Council for Science and Technology evolved a management plan which involved:[4]

- Opening of sluice gates during monsoon

- Monitoring of water quality migration period

- Fencing some of the selected portions from encroachment

- Afforestation of the catchment area

- Survey, mapping & notification

- Soil Conservation

- Education and Public awareness

World wetlands day

On February 2, 2003 the World Wetlands Day was celebrated at Harike with the watchword "No-wetlands-No Water", which also marked the "International Year of Freshwater".[4]

Gallery

- Pygmy goose

_I3_IMG_9638.jpg) Yellow-crowned woodpecker

Yellow-crowned woodpecker Brown-headed gull

Brown-headed gull Blackheaded gull

Blackheaded gull_Harrier.jpg) Hen harrier

Hen harrier Cetti's warbler

Cetti's warbler Nelumbo nucifera –Lotus

Nelumbo nucifera –Lotus

Prosopis juliflora

Prosopis juliflora

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.topnews.in/visit-harike-pattan-bird-sanctuary-offers-joy-lifetime-218657

- 1 2 3 4 http://ramsar.wetlands.org/Portals/15/India.pdf Wetland name: Harike Lake

- 1 2 3 http://www.ramsar.org/forum/forum_india_harike.htm Update on the Harike Wetland, India

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 http://www.punenvis.nic.in/water_wetland_status.htm. Status of wetlands

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 http://www.pscst.com/en/pdfs/Conservation%20Programmes%20for%20Wetlands.pdf Conservation Programmes for Wetlands

- ↑ http://www.india9.com/i9show/Harike-Wildlife-Sanctuary-17106.htm

- 1 2 3 http://www.toursandtravelsinindia.com/nationalpark/harike_pattan_sanctuary.html Harike Pattan Sanctuary

- ↑ http://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/wetland_news/index.cfm The dolphin returns

- ↑ http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/8966/0

- ↑ http://diprpunjab.gov.in/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=104:punjab-government-embarks-an-ambitious-programme-for-re-introduction-of-gharial-in-the-river-satluj-beas-system&catid=37:english-news&Itemid=62

- ↑ http://www.gisdevelopment.net/aars/acrs/1997/ts7/ts7008.asp

- ↑ http://www.springerlink.com/content/75355h4221325169/ Impact of Declining Trend of Flow on Harike Wetland,India