Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden is an art museum beside the National Mall, in Washington, D.C., the United States. The museum was initially endowed during the 1960s with the permanent art collection of Joseph H. Hirshhorn. It was designed by architect Gordon Bunshaft and is part of the Smithsonian Institution. It was conceived as the United States' museum of contemporary and modern art and currently focuses its collection-building and exhibition-planning mainly on the post–World War II period, with particular emphasis on art made during the last 50 years.[1]

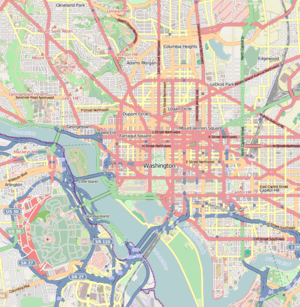

The Hirshhorn is sited exactly halfway between the Washington Monument and the US Capitol, anchoring the southernmost end of the so-called L’Enfant axis (perpendicular to the Mall’s green carpet). The National Archives/National Gallery of Art Sculpture Garden across the Mall, and the National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian American Art building several blocks to the north, also mark this pivotal axis, a key element of both the 1791 city plan by Pierre L’Enfant and the 1901 MacMillan Plan.[2]

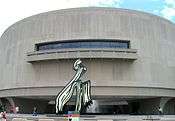

The building itself is an attraction, likened by some to a large spacecraft parked on the National Mall. The building is an open cylinder elevated on four massive "legs," with a large fountain occupying the central courtyard. Before architect Gordon Bunshaft designed the building, the Smithsonian staff reportedly told him that, if it did not provide a striking contrast to everything else in the city, then it would be unfit for housing a modern art collection.

History

Founding

In the late 1930s, the United States Congress mandated an art museum for the National Mall. At the time, the only venue for visual art was the National Gallery of Art, which focuses on Dutch, French, and Italian art. During the 1940s World War II shifted the project into the background.

Meanwhile, Joseph H. Hirshhorn, now in his forties and enjoying great success from uranium-mining investments, began creating his collection from classic French Impressionism to works by living artists, American modernism of the early 20th century, and sculpture. Then, in 1955, Hirshhorn sold his uranium interests for more than $50-million. He expanded his collection to warehouses, an apartment in New York City, and an estate in Greenwich, Connecticut, with extensive area for sculpture.

A 1962 sculpture show at New York's Guggenheim Museum awakened an international art community to the breadth of Hirshhorn's holdings. Word of his collection of modern and contemporary paintings also circulated, and institutions in Italy, Israel, Canada, California, and New York City vied for the collection. President Lyndon B. Johnson and Smithsonian Secretary S. Dillon Ripley successfully campaigned for a new museum on the National Mall.

In 1966, an Act of Congress established the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution. Most of the funding was federal, but Hirshhorn later contributed $1-million toward construction. Joseph and his fourth wife, Olga Zatorsky Hirshhorn, visited the White House. The groundbreaking was in 1969.

Abram Lerner (born 1913) is named the founding Director. He oversaw research, conservation, and installation of more than 6,000 items brought from the Hirshhorns' Connecticut estate and other properties to Washington, DC.

Joseph Hirshhorn spoke at the inauguration (1974), saying:

It is an honor to have given my art collection to the people of the United States as a small repayment for what this nation has done for me and others like me who arrived here as immigrants. What I accomplished in the United States I could not have accomplished anywhere else in the world.

One million visitors saw the 850-work inaugural show in the first six months.

Institutional leadership

In 1984, James T. Demetrion, fourteen-year director of the Des Moines Art Center in Iowa, succeeded Abram Lerner as the Hirshhorn's director. Art collector and retail store founder Sydney Lewis of Richmond, Virginia, succeeded Senator Daniel P. Moynihan as board chairman.[3] Mr. Demetrion held the post for more than 17 years.

Ned Rifkin became director in February 2002, returning to the Hirshhorn after directorship positions at the Menil Collection in Texas and the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia. Rifkin was previously chief curator of the Hirshhorn from 1986 until 1991. In October 2003, Rifkin was named Under Secretary for Art of the Smithsonian.

In 2005, Olga Viso was named director of the Hirshhorn. Viso joined the curatorial department of the Hirshhorn in 1995 as assistant curator, was named associate curator in 1998, and served as curator of contemporary art from 2000 to 2003. In October 2003, Viso was named deputy director of the Hirshhorn, a post she held until her 2005 promotion to director. After two years, Ms. Viso accepted the position of Director of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, departing in December 2007.

Chief Curator and Deputy Director Kerry Brougher served as Acting Director for more than a year until an international search led to the hiring of Richard Koshalek, who was named the fifth director of the Hirshhorn in February, 2009.

Richard Koshalek (born 1942) was president of Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, Calif., from 1999 until January 2009. Before that, he served as director of The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles for nearly 20 years. At both institutions, he was noted for his commitment to new artistic initiatives, including commissioned works, scholarly exhibitions and publications and the building of new facilities that garnered architectural acclaim. He worked with architect Frank Gehry on the design and construction of MOCA's Geffen Contemporary (1983), a renovated warehouse popularly known as the Temporary Contemporary. He also worked with the Japanese architect Arata Isozaki on the museum's permanent home in Los Angeles (1986). Koshalek resigned in 2013 after the Bloomberg Bubble controversy (see below).

On June 5, 2014, Hirshhorn trustees announced that they had hired Melissa Chiu, director of Asia Society Museum in New York City, to be the Hirshhorn's new director. Chiu, who was born in Darwin, Australia, is a scholar of contemporary Chinese art. Chiu oversaw the Hirshhorn's 40th anniversary celebration in the fall of 2014.[4] Chiu began her tenure at the Hirshhorn in September 2014.[5]

Collection highlights

Notable artists in the collection include: Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Mary Cassatt, Thomas Eakins, Henry Moore, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline, Hans Hofmann, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, John Chamberlain, Francis Bacon, Willem de Kooning, Milton Avery, Ellsworth Kelly, Louise Nevelson, Arshile Gorky, Edward Hopper, Larry Rivers, and Raphael Soyer among others. Outside the museum is a sculpture garden, featuring works by artists including Auguste Rodin, David Smith, Alexander Calder, Jeff Koons and others.[6]

Yoko Ono’s Wish Tree for Washington, DC, a permanent installation in the Sculpture Garden (since 2007), now includes contributions from all over the world.[7]

Bloomberg Bubble controversy

In 2009, then Director Richard Koshalek announced that an inflatable structure would be erected over the Hirshhorn's central plaza to create a new public space. The Seasonal Inflatable Structure, to be called the "Bloomberg Bubble," was due to be erected in 2013 and would be inflated annually for one two-month period. It was supposed to create a 14,000-square-foot space for performance and lectures.[8][9] Designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the proposal won a progressive architecture award from Architect magazine.[10]

Hirshhorn officials began reconsidering the Bubble in 2013. Construction cost estimates for the structure more than tripled to $15.5 million from $5 million, and no major gifts for the project were received between 2010 and May 2013. A Hirshhorn study also concluded that the cost of programming (such as symposia and special events) using the Bubble were likely to run a $2.8 million annual deficit. The Hirshhorn's board of directors evenly split on a vote to proceed with the project in May 2013. In the wake of the vote, seen as a referendum on his leadership, museum director Richard Koshalek announced he would resign by the end of 2013.[11] Constance Caplan, chair of the museum's board of trustees, resigned on July 8, 2013. She cited what the Washington Post characterized as "a board, a museum and the larger Smithsonian Institution at a crossroads, roiled by a lack of transparency, trust, vision and good faith". Four of the board's 15 members resigned between June 2012 and April 2013, and three more (including Caplan) in May, June and July 2013.[12]

sculpture by Pablo Serrano

Architecture

The museum was designed by architect Gordon Bunshaft (1909-1990) and provides 60,000 square feet (5,600 m2) of exhibition space inside and nearly four acres outside in its two-level Sculpture Garden and plaza. The New York Times described it as: "a fortress of a building that works as a museum." An original plan with a reflecting pool across the Mall was approved in July 1967. When excavation started, a controversy arose, resulting in a revised design, with a smaller footprint, which was approved on July 1, 1971.[13]

- Technical Information[14]

- Building and walls surfaced with precast concrete aggregate of “Swenson” pink granite

- Building is 231 feet in diameter; interior court, 115 feet; fountain, 60 feet

- Building is 82 feet high, elevated 14 feet on four massive, sculptural piers

- 60,000 square feet of exhibition space on three floors

- 197,000 square feet of total exhibition space, indoors and outdoors

- 274-seat auditorium (lower level)

- 2.7 acres around and under the museum building

- 1.3-acre sculpture garden across Jefferson Drive sunken 6–14 feet below street level, ramped for accessibility

- Second- and third-floor galleries have 15-foot-high walls, with exposed 3-foot-deep coffered ceilings

- Lower level includes exhibition space, storage, workshops, offices

- Fourth floor includes offices, storage

- Architectural timeline

- 1969. The Hirshhorn Museum groundbreaking takes place on the former site of the Army Medical Museum and Library (built 1887) after the brick structure is demolished. A controversy soon develops over naming a building on the historic National Mall after a living person, as well as the new federal museum's modern look and intrusively expansive sculptural grounds.

- 1971. Amid this climate of controversy, Bunshaft's original conception for the Sculpture Garden-an elongated, sunken rectangle crossing the Mall with a large reflecting pool-is abandoned. He prepares a new design based on an idea outlined by art critic Benjamin Forgey in a Washington Star article. The new adaptation shifts the garden's Mall orientation from perpendicular to parallel and reduces its size from 2 acres (8,100 m2) to 1.3 acres (5,300 m2). The design is deliberately stark, using gravel surfaces and minimal plantings to visually emphasize the works of art.

- 1974. The museum opens with three floors of painting galleries, a fountain plaza for sculpture, and the Sculpture Garden. In preparation for the opening, Hirshhorn curators and staff spend several months scrupulously planning the locations of artworks, both indoors and outdoors. Lightweight foam-core "dummy" sculptures are used to resolve the final placement of works in the garden. The originals, many of which had been airlifted from Hirshhorn's Connecticut estate onto flatbed trucks for transport, are put into place in the weeks before the opening.

- 1981. Closed since the summer of 1979, the Sculpture Garden reopens in September after a renovation and redesign by Lester Collins, a well-known landscape architect and founder of the Innesfree Foundation. The design introduces plantings, paved surfaces, accessibility ramps, and areas of lawn.

- 1985. The Museum Shop is moved to the lobby, increasing exhibition space at its former location on the lower level.

- 1993. Closed since December 1991, the Hirshhorn Plaza reopens after a renovation and redesign by landscape architect James Urban. The 2.7-acre (11,000 m2) area around and under the building is repaved in two tones of gray granite, and raised areas of grass and trees are added to the east and west.

- 2014. The Museum Shop is moved back to the lower level.

- Comments and criticisms

- "The whole complex has been designed as one composition... Bunshaft's design is not concerned with the grandeur of the Mall. It is concerned with the greater grandeur of his museum and it gives us an awful lot of beaux-arts pavement and pomposity that no longer seem to suit the taste and style of our times." [Preliminary design criticized] Wolf Von Eckhardt, The Washington Post, February 6, 1971.

- "The circular plan is not only clear, but also provides a pleasant processional sequence that goes a long way.... The fortress quality of the Hirshhorn suggests some rather obvious thoughts about the nature of housing art in our time. But the building's architecture... is less the product of a desire to make a statement... than it is a logical progression in aesthetic development.... " Paul Goldberger, The New York Times, October 2, 1974.

- "[The building] is known around Washington as the bunker or gas tank, lacking only gun emplacements or an Exxon sign... It totally lacks the essential factors of esthetic strength and provocative vitality that make genuine 'brutalism' a positive and rewarding style. This is born-dead, neo-penitentiary modern. Its mass is not so much aggressive or overpowering as merely leaden." Ada Louise Huxtable, The New York Times, October 6, 1974.

- "The parched severity of [the original Sculpture Garden] was not without merit, but the appeal was more to the mind than to the senses, more theoretical than practical.... The new design reinforces the identity of the garden as a welcoming urban park.... [This] park for art...serves the sculpture. The divisions of the space prove essential accents; artworks pop in and out of view as the spectator moves about the space...." Benjamin Forgey, The Washington Post, September 12, 1981.

- "[The Hirshhorn is] the biggest piece of abstract art in town - a huge, hollowed cylinder raised on four massive piers, in absolute command of its walled compound on the Mall.... The circular fountain...is a grand concoction...that for good reason has become the museum's visual trademark." Benjamin Forgey, The Washington Post, November 4, 1989.

Management

In 2013, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden drew around 645,000 visitors. It has a budget of $8 million, which does not include the $10 to $12 million in operational support supplied by the Smithsonian Institution.[15]

In 2007, the Hirshhorn began hosting After Hours Parties three times a year. These events allowed the museum to give a venue to underground and avante-garde local artists, allowing itself to be turned into not only a night club, but a club where the art on the walls is the real deal. In 2009, Hirshhorn After Hours collaborated with The Pink Line Project, where the Pink Line Project hosted the VIP Lounge.

Gallery

Hirshhorn Museum (exterior)

Hirshhorn Museum (exterior) Hirshhorn Museum (entrance)

Hirshhorn Museum (entrance)_2.jpg) Hirshhorn Museum (center)

Hirshhorn Museum (center).jpg) Hirshhorn Museum (underneath)

Hirshhorn Museum (underneath) Courtyard and fountain

Courtyard and fountain.jpg) Hirshhorn Museum (inner gallery)

Hirshhorn Museum (inner gallery)_1.jpg) Hirshhorn Museum (outer gallery)

Hirshhorn Museum (outer gallery).jpg) Hirshhorn Museum (basement gallery)

Hirshhorn Museum (basement gallery)

See also

- Antipodes by Jim Sanborn

- Needle Tower by Kenneth Snelson

- Throwback by Tony Smith

- Army Medical Museum and Library

- DC Environmental Film Festival

- Gordon Bunshaft

- Joseph H. Hirshhorn

- Last Conversation Piece

- National Gallery of Art Sculpture Garden

- Smithsonian Institution

- Tippet Rise Art Center - two Calders are on loan from to Tippet Rise from Hirshhorn Museum (2016)

- Judith K. Zilczer

References

- ↑ Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden: About, ARTINFO, 2008, retrieved 2008-07-28

- ↑ "History of the Hirshhorn: The Architect". Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ↑ Hirshhorn Museum Official Site

- ↑ Cohen, Patricia; Vogel, Carol (June 5, 2014). "Asia Society Museum Director to Lead Hirshhorn". The New York Times. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ↑ Parker, Lonnae O'Neal (June 5, 2014). "Hirshhorn Names N.Y. Asia Society Museum's Melissa Chiu As New Director". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ↑ About Joseph Hirshhorn Retrieved February 8, 2010

- ↑ "Yoko Ono: Wish Tree [Hirshhorn, Washington DC, USA]". IMAGINE PEACE.

- ↑ Maura Judkis (March 23, 2012). "Hirshhorn 'Bubble' to be called Bloomberg Balloon". Washington Post.

- ↑ "Liz Diller: A giant bubble for debate". TED 2012. March 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- ↑ Vernon Mays (February 9, 2011). "P/A AWARDS Award: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Seasonal Expansion". ARCHITECT.

- ↑ Parker, Lonnae O'Neal. "Hirshhorn Director Plans to Resign After Board Splits on 'Bubble' Project." Washington Post. May 23, 2013. Accessed 2013-05-24.

- ↑ Parker, Lonnae O'Neal. "Constance Caplan, Chair of Hirshhorn Museum Board, Announces Resignation." Washington Post. July 10, 2013. Accessed 2013-07-10.

- ↑ A Garden for Art, Valerie J. Fletcher, LOC # 97-61991, p.19-20

- ↑ Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden Official Website: Technical Information

- ↑ Patricia Cohen and Carol Vogel (June 5, 2014), Asia Society Museum Director to Lead Hirshhorn New York Times.

Bibliography

- Hughes, Emmet John. "Joe Hirshhorn, the Brooklyn Uranium King." Fortune Magazine, 55 (November 1956): pp. 154–56.

- Hyams, Barry. Hirshhorn: Medici from Brooklyn. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1979.

- Jacobs, Jay. "Collector: Joseph Hirshhorn." Art in America, 57 (July–August 1969): pp. 56–71.

- Lewis, JoAnn. "Every Day Is Sunday for Joe Hirshhorn." Art News, 78 (Summer 1979): pp. 56–61.

- Modern Sculpture from the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Collection. Exhibition catalog. New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1962.

- Rosenberg, Harold. "The Art World: The Hirshhorn." The New Yorker, vol. L, no. 37 (November 4, 1974): pp. 156–61.

- Russell, John. "Joseph Hirshhorn Dies; Financier, Art Patron." The New York Times (September 2, 1981): pp. A1-A17.

- Saarinen, Aline. "Little Man in a Big Hurry." The Proud Possessors (New York: Random House, 1958), pp. 269–86.

- Taylor, Kendall. "Three Men and Their Museums: Solomon Guggenheim, Joseph Hirshhorn, Roy Neuberger and the Art They Collected." Museum 2 (January–February 1982): pp. 80–86."

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hirshhorn Museum. |

- Hirshhorn Museum official website

- Ono contributes to 'Wish Tree' - Artist Yoko Ono dedicates a "Wish Tree" at the Hirshhorn Museum's Sculpture Garden

- All Eyes on the Hirshhorn, But It Wasn't Always Pretty (or Round) - good background blog post on the history of the museum