Hodgkin's lymphoma

| Hodgkin's lymphoma | |

|---|---|

| Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin's disease[1] | |

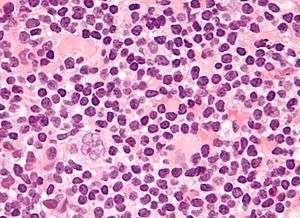

|

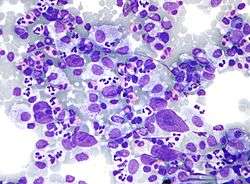

Micrograph showing Hodgkin lymphoma (Field stain) | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Hematology and oncology |

| ICD-10 | C81 |

| ICD-9-CM | 201 |

| ICD-O | 9650/3-9667/3 |

| DiseasesDB | 5973 |

| MedlinePlus | 000580 |

| eMedicine | med/1022 |

| Patient UK | Hodgkin's lymphoma |

| MeSH | D006689 |

Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) is a type of lymphoma, which is generally believed to result from white blood cells of the lymphocyte kind.[2] Symptoms may include fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Often there will be non-painful enlarged lymph nodes in the neck, under the arm, or in the groin. Those affected may feel tired or be itchy.[3]

About half of cases of Hodgkin's lymphoma are due to Epstein–Barr virus (EBV).[4] Other risk factors include a family history of the condition and having HIV/AIDS.[3][4] There are two major types of Hodgkin lymphoma: classical Hodgkin lymphoma and nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma.[5] Diagnosis is by finding Hodgkin's cells such as multinucleated Reed–Sternberg cells (RS cells) in lymph nodes.[3]

Hodgkin lymphoma may be treated with chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and stem cell transplant. The choice of treatment often depends on how advanced the cancer is and whether or not it has favorable features.[6] In early disease a cure is often possible.[7] The percentage of people who survive five years in the United States is 86%.[5] For those under the age of 20 rates of survival are 97%.[8] Radiation and some chemotherapy drugs, however, increase the risk of other cancers, heart disease, or lung disease over the subsequent decades.[7]

In 2013 about 725,000 people had Hodgkin's lymphoma and 24,000 died.[9][10] In the United States 0.2% of people are affected at some point in their life. The most common age of diagnosis is between 20 and 40 years old.[5] It was named after the English physician Thomas Hodgkin, who first described the condition in 1832.[7][11]

Signs and symptoms

Patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma may present with the following symptoms:

- Lymph nodes: the most common symptom of Hodgkin's is the painless enlargement of one or more lymph nodes, or lymphadenopathy. The nodes may also feel rubbery and swollen when examined. The nodes of the neck and shoulders (cervical and supraclavicular) are most frequently involved (80–90% of the time, on average). The lymph nodes of the chest are often affected, and these may be noticed on a chest radiograph.

- Itchy skin

- Night sweats

- Unexplained weight loss

- Splenomegaly: enlargement of the spleen occurs in about 30% of people with Hodgkin's lymphoma. The enlargement, however, is seldom massive and the size of the spleen may fluctuate during the course of treatment.

- Hepatomegaly: enlargement of the liver, due to liver involvement, is present in about 5% of cases.

- Hepatosplenomegaly: the enlargement of both the liver and spleen caused by the same disease.

- Pain following alcohol consumption: classically, involved nodes are painful after alcohol consumption, though this phenomenon is very uncommon,[12] occurring in only two to three percent of people with Hodgkin's lymphoma,[13] thus having a low sensitivity. On the other hand, its specificity is high enough for it to be regarded as a pathognomonic sign of Hodgkin lymphoma.[13] The pain typically has an onset within minutes after ingesting alcohol, and is usually felt as coming from the vicinity where there is an involved lymph node.[13] The pain has been described as either sharp and stabbing or dull and aching.[13]

- Back pain: nonspecific back pain (pain that cannot be localised or its cause determined by examination or scanning techniques) has been reported in some cases of Hodgkin's lymphoma. The lower back is most often affected.

- Red-coloured patches on the skin, easy bleeding and petechiae due to low platelet count (as a result of bone marrow infiltration, increased trapping in the spleen etc.—i.e. decreased production, increased removal)

- Systemic symptoms: about one-third of patients with Hodgkin's disease may also present with systemic symptoms, including low-grade fever; night sweats; unexplained weight loss of at least 10% of the patient's total body mass in six months or less, itchy skin (pruritus) due to increased levels of eosinophils in the bloodstream; or fatigue (lassitude). Systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and weight loss are known as B symptoms; thus, presence of fever, weight loss, and night sweats indicate that the patient's stage is, for example, 2B instead of 2A.[14]

- Cyclical fever: patients may also present with a cyclical high-grade fever known as the Pel-Ebstein fever,[15] or more simply "P-E fever". However, there is debate as to whether the P-E fever truly exists.[16]

- Nephrotic syndrome can occur in individuals with Hodgkin's lymphoma and is most commonly caused by minimal change disease.[17]

Diagnosis

Hodgkin's lymphoma must be distinguished from non-cancerous causes of lymph node swelling (such as various infections) and from other types of cancer. Definitive diagnosis is by lymph node biopsy (usually excisional biopsy with microscopic examination). Blood tests are also performed to assess function of major organs and to assess safety for chemotherapy. Positron emission tomography (PET) is used to detect small deposits that do not show on CT scanning. PET scans are also useful in functional imaging (by using a radiolabeled glucose to image tissues of high metabolism). In some cases a Gallium Scan may be used instead of a PET scan.

Types

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma (excluding nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin's lymphoma) can be subclassified into four pathologic subtypes based upon Reed–Sternberg cell morphology and the composition of the reactive cell infiltrate seen in the lymph node biopsy specimen (the cell composition around the Reed–Sternberg cell(s)).

| Name | Description | ICD-10 | ICD-O |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nodular sclerosing HL | Is the most common subtype and is composed of large tumor nodules showing scattered lacunar classical RS cells set in a background of reactive lymphocytes, eosinophils and plasma cells with varying degrees of collagen fibrosis/sclerosis. | C81.1 | M9663/3 |

| Mixed-cellularity subtype | Is a common subtype and is composed of numerous classic RS cells admixed with numerous inflammatory cells including lymphocytes, histiocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells without sclerosis. This type is most often associated with EBV infection and may be confused with the early, so-called 'cellular' phase of nodular sclerosing CHL. | C81.2 | M9652/3. |

| Lymphocyte-rich | Is a rare subtype, show many features which may cause diagnostic confusion with nodular lymphocyte predominant B-cell Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma (B-NHL). This form also has the most favorable prognosis. | C81.0 | M9651/3 |

| Lymphocyte depleted | Is a rare subtype, composed of large numbers of often pleomorphic RS cells with only few reactive lymphocytes which may easily be confused with diffuse large cell lymphoma. Many cases previously classified within this category would now be reclassified under anaplastic large cell lymphoma.[18] | C81.3 | M9653/3 |

| Unspecified | C81.9 | M9650/3 |

_mixed_cellulary_type.jpg)

Nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin's lymphoma expresses CD20, and is not currently considered a form of classical Hodgkin's lymphoma.

For the other forms, although the traditional B-cell markers (such as CD20) are not expressed on all cells,[18] Reed–Sternberg cells are usually of B cell origin.[19][20] Although Hodgkin's is now frequently grouped with other B-cell malignancies, some T-cell markers (such as CD2 and CD4) are occasionally expressed.[21] However, this may be an artifact of the ambiguity inherent in the diagnosis.

Hodgkin cells produce interleukin-21 (IL-21), which was once thought to be exclusive to T-cells. This feature may explain the behavior of classical Hodgkin's lymphoma, including clusters of other immune cells gathered around HL cells (infiltrate) in cultures.[22]

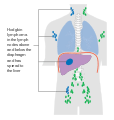

Staging

The staging is the same for both Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphomas.

After Hodgkin lymphoma is diagnosed, a patient will be staged: that is, they will undergo a series of tests and procedures that will determine what areas of the body are affected. These procedures may include documentation of their histology, a physical examination, blood tests, chest X-ray radiographs, computed tomography (CT)/Positron emission tomography (PET)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, and usually a bone marrow biopsy. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan is now used instead of the gallium scan for staging. On the PET scan, sites involved with lymphoma light up very brightly enabling accurate and reproducible imaging.[23] In the past, a lymphangiogram or surgical laparotomy (which involves opening the abdominal cavity and visually inspecting for tumors) were performed. Lymphangiograms or laparotomies are very rarely performed, having been supplanted by improvements in imaging with the CT scan and PET scan.

On the basis of this staging, the patient will be classified according to a staging classification (the Ann Arbor staging classification scheme is a common one):

- Stage I is involvement of a single lymph node region (I) (mostly the cervical region) or single extralymphatic site (Ie);

- Stage II is involvement of two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm (II) or of one lymph node region and a contiguous extralymphatic site (IIe);

- Stage III is involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm, which may include the spleen (IIIs) and/or limited contiguous extralymphatic organ or site (IIIe, IIIes);

- Stage IV is disseminated involvement of one or more extralymphatic organs.

The absence of systemic symptoms is signified by adding "A" to the stage; the presence of systemic symptoms is signified by adding "B" to the stage. For localised extranodal extension from mass of nodes that does not advance the stage, subscript "E" is added. Splenic involvement is signified by adding "S" to the stage. The inclusion of "bulky disease" is signified by "X".

-

Stage 1 Hodgkin's lymphoma

-

Stage 2 Hodgkin's lymphoma

-

Stage 3 Hodgkin's lymphoma

-

Stage 4 Hodgkin's lymphoma

Pathology

- Macroscopy

Affected lymph nodes (most often, laterocervical lymph nodes) are enlarged, but their shape is preserved because the capsule is not invaded. Usually, the cut surface is white-grey and uniform; in some histological subtypes (e.g. nodular sclerosis) a nodular aspect may appear.

A fibrin ring granuloma may be seen.

- Microscopy

Microscopic examination of the lymph node biopsy reveals complete or partial effacement of the lymph node architecture by scattered large malignant cells known as Reed-Sternberg cells (RSC) (typical and variants) admixed within a reactive cell infiltrate composed of variable proportions of lymphocytes, histiocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells. The Reed–Sternberg cells are identified as large often bi-nucleated cells with prominent nucleoli and an unusual CD45-, CD30+, CD15+/- immunophenotype. In approximately 50% of cases, the Reed–Sternberg cells are infected by the Epstein–Barr virus.

Characteristics of classic Reed–Sternberg cells include large size (20–50 micrometres), abundant, amphophilic, finely granular/homogeneous cytoplasm; two mirror-image nuclei (owl eyes) each with an eosinophilic nucleolus and a thick nuclear membrane (chromatin is distributed close to the nuclear membrane).

Variants:

- Hodgkin cell (atypical mononuclear RSC) is a variant of RS cell, which has the same characteristics, but is mononucleated.

- Lacunar RSC is large, with a single hyperlobulated nucleus, multiple, small nucleoli and eosinophilic cytoplasm which is retracted around the nucleus, creating an empty space ("lacunae").

- Pleomorphic RSC has multiple irregular nuclei.

- "Popcorn" RSC (lympho-histiocytic variant) is a small cell, with a very lobulated nucleus, small nucleoli.

- "Mummy" RSC has a compact nucleus with no nucleolus and basophilic cytoplasm.

Hodgkin's lymphoma can be sub-classified by histological type. The cell histology in Hodgkin's lymphoma is not as important as it is in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: the treatment and prognosis in classic Hodgkin's lymphoma usually depends on the stage of disease rather than the histotype.

Management

Patients with early stage disease (IA or IIA) are effectively treated with radiation therapy or chemotherapy. The choice of treatment depends on the age, sex, bulk and the histological subtype of the disease. Adding localised radiation therapy after the chemotherapy regimen controls the tumors better and provides a better chance for survival than chemotherapy alone.[24] Patients with later disease (III, IVA, or IVB) are treated with combination chemotherapy alone. Patients of any stage with a large mass in the chest are usually treated with combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

| MOPP | ABVD | Stanford V | BEACOPP |

|---|---|---|---|

| The original treatment for Hodgkin's was MOPP (medicine). The abbreviation stands for the four drugs Mustargen, Oncovin (also known as Vincristine), Prednisone and Procarbazine (also known as Matulane). The treatment is usually administered in four week cycles, often for six cycles. MSD and VCR are administered intravenously, while procarbazine and prednisone are pills taken orally. MOPP was the first combination chemotherapy brought in that achieved a high success rate. It was developed at the National Cancer Institute in the 1960s by a team that included Vincent DeVita, Jr..

Although no longer the most effective combination, MOPP is still used after relapse or where the patient has certain allergies or lung or heart problems which prevents the use of another regimen. |

Currently, the ABVD chemotherapy regimen is the standard treatment of Hodgkin's disease in the US. The abbreviation stands for the four drugs Adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine. Developed in Italy in the 1970s, the ABVD treatment typically takes between six and eight months, although longer treatments may be required. | The newer Stanford V regimen is typically only half as long as the ABVD but involves a more intensive chemotherapy schedule and incorporates radiation therapy. In a randomised controlled study in Italy, Stanford V was inferior to ABVD;[25] however, this study has been heavily criticized due to its incorrect administration of radiotherapy, diverging from the original Stanford V protocol.[26] | BEACOPP is a form of treatment for stages > II mainly used in Europe. The cure rate with the BEACOPP esc. regimen is approximately 10–15% higher than with standard ABVD in advanced stages. This was shown in a paper in The New England Journal of Medicine (Diehl et al.), but US physicians still favor ABVD, maybe because some physicians think that BEACOPP induces more secondary leukemia. However, this seems negligible compared to the higher cure rates. BEACOPP is more expensive because of the requirement for concurrent treatment with GCSF to increase production of white blood cells. Currently, the German Hodgkin Study Group tests 8 cycles (8x) BEACOPP esc vs. 6x BEACOPP esc vs. 8x BEACOPP-14 baseline (HD15-trial).[27] |

| Mustargen | Doxorubicin | Doxorubicin | Doxorubicin |

| Oncovin | Bleomycin | Bleomycin | Bleomycin |

| Prednisone | Vinblastine | Vinblastine, Vincristine | Vincristine |

| Procarbazine | Dacarbazine | Mechlorethamine | Cyclophosphamide, Procarbazine |

| Etoposide | Etoposide | ||

| Prednisone | Prednisone |

It should be noted that the common non-Hodgkin's treatment, rituximab (which is a monoclonal antibody against CD20) is not routinely used to treat Hodgkin's lymphoma due to the lack of CD20 surface antigens in most cases. The use of rituximab in Hodgkin's lymphoma, including the lymphocyte predominant subtype has been reviewed recently.[28]

Although increased age is an adverse risk factor for Hodgkin's lymphoma, in general elderly patients without major comorbidities are sufficiently fit to tolerate standard therapy, and have a treatment outcome comparable to that of younger patients. However, the disease is a different entity in older patients and different considerations enter into treatment decisions.[29]

For Hodgkin's lymphomas, radiation oncologists typically use external beam radiation therapy (sometimes shortened to EBRT or XRT). Radiation oncologists deliver external beam radiation therapy to the lymphoma from a machine called linear accelerator which produces high energy X Rays and Electrons. Patients usually describe treatments as painless and similar to getting an X-ray. Treatments last less than 30 minutes each.

For lymphomas, there are a few different ways radiation oncologists target the cancer cells. Involved field radiation is when the radiation oncologists give radiation only to those parts of the patient's body known to have the cancer. Very often, this is combined with chemotherapy. Radiation therapy directed above the diaphragm to the neck, chest and/or underarms is called mantle field radiation. Radiation to below the diaphragm to the abdomen, spleen and/or pelvis is called inverted-Y field radiation. Total nodal irradiation is when the therapist gives radiation to all the lymph nodes in the body to destroy cells that may have spread.[30]

Adverse effects

The high cure rates and long survival of many patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma has led to a high concern with late adverse effects of treatment, including cardiovascular disease and second malignancies such as acute leukemias, lymphomas, and solid tumors within the radiation therapy field. Most patients with early-stage disease are now treated with abbreviated chemotherapy and involved-field radiation therapy rather than with radiation therapy alone. Clinical research strategies are exploring reduction of the duration of chemotherapy and dose and volume of radiation therapy in an attempt to reduce late morbidity and mortality of treatment while maintaining high cure rates. Hospitals are also treating those who respond quickly to chemotherapy with no radiation.

In childhood cases of Hodgkin's lymphoma, long-term endocrine adverse effects are a major concern, mainly gonadal dysfunction and growth retardation. Gonadal dysfunction seems to be the most severe endocrine long-term effect, especially after treatment with alkylating agents and/or pelvic radiotherapy.[31]

Prognosis

Treatment of Hodgkin's disease has been improving over the past few decades. Recent trials that have made use of new types of chemotherapy have indicated higher survival rates than have previously been seen. In one recent European trial, the 5-year survival rate for those patients with a favorable prognosis was 98%, while that for patients with worse outlooks was at least 85%.[32]

In 1998, an international effort[33] identified seven prognostic factors that accurately predict the success rate of conventional treatment in patients with locally extensive or advanced stage Hodgkin's lymphoma. Freedom from progression (FFP) at 5 years was directly related to the number of factors present in a patient. The 5-year FFP for patients with zero factors is 84%. Each additional factor lowers the 5-year FFP rate by 7%, such that the 5-year FFP for a patient with 5 or more factors is 42%.

The adverse prognostic factors identified in the international study are:

- Age ≥ 45 years

- Stage IV disease

- Hemoglobin < 10.5 g/dl

- Lymphocyte count < 600/µl or < 8%

- Male

- Albumin < 4.0 g/dl

- White blood count ≥ 15,000/µl

Other studies have reported the following to be the most important adverse prognostic factors: mixed-cellularity or lymphocyte-depleted histologies, male sex, large number of involved nodal sites, advanced stage, age of 40 years or more, the presence of B symptoms, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and bulky disease (widening of the mediastinum by more than one third, or the presence of a nodal mass measuring more than 10 cm in any dimension.)

More recently, use of positron emission tomography (PET) early after commencing chemotherapy has demonstrated to have powerful prognostic ability.[34] This enables assessment of an individual's response to chemotherapy as the PET activity switches off rapidly in patients who are responding. In this study,[34] after two cycles of ABVD chemotherapy, 83% of patients were free of disease at 3 years if they had a negative PET versus only 28% in those with positive PET scans. This prognostic power exceeds conventional factors discussed above. Several trials are underway to see if PET-based risk adapted response can be used to improve patient outcomes by changing chemotherapy early in patients who are not responding.

Epidemiology

Unlike some other lymphomas, whose incidence increases with age, Hodgkin's lymphoma has a bimodal incidence curve; that is, it occurs most frequently in two separate age groups, the first being young adulthood (age 15–35) and the second being in those over 55 years old although these peaks may vary slightly with nationality.[36] Overall, it is more common in males, except for the nodular sclerosis variant, which is slightly more common in females. The annual incidence of Hodgkin's lymphoma is 2.7 per 100,000 per persons per year, and the disease accounts for slightly less than 1% of all cancers worldwide.[37]

In 2010, globally it resulted in about 18,000 deaths down from 19,000 in 1990.[1]

The incidence of Hodgkin's lymphoma is increased in patients with HIV infection.[38] In contrast to many other lymphomas associated with HIV infection it occurs most commonly in patients with higher CD4 T cell counts.

UK

Hodgkin lymphoma accounts for less than 1% of all cancer cases and deaths in the UK. Around 1,800 people were diagnosed with the disease in 2011, and around 330 people died in 2012.[39]

History

.jpg)

Hodgkin's lymphoma was first described in an 1832 report by Thomas Hodgkin, although Hodgkin noted that perhaps the earliest reference to the condition was provided by Marcello Malpighi in 1666.[40][11] While occupied as museum curator at Guy's Hospital, Hodgkin studied seven patients with painless lymph node enlargement. Of the seven cases, two were patients of Richard Bright, one was of Thomas Addison, and one was of Robert Carswell.[40] Carswell's report of this seventh patient was accompanied by numerous illustrations that aided early descriptions of the disease.[41]

Hodgkin's report on these seven patients, entitled "On some morbid appearances of the absorbent glands and spleen", was presented to the Medical and Chirurgical Society in London in January 1832 and was subsequently published in the society's journal, Medical-Chirurgical Society Transactions.[40] Hodgkin's paper went largely unnoticed, however, even despite Bright highlighting it in an 1838 publication.[40] Indeed, Hodgkin himself did not view his contribution as particularly significant.[42]

In 1856, Samuel Wilks independently reported on a series of patients with the same disease that Hodgkin had previously described.[42] Wilks, a successor to Hodgkin at Guy's Hospital, was unaware of Hodgkin's prior work on the subject. Bright made Wilks aware of Hodgkin's contribution and in 1865, Wilks published a second paper, entitled "Cases of enlargement of the lymphatic glands and spleen", in which he called the disease "Hodgkin's disease" in honor of his predecessor.[42]

Theodor Langhans and WS Greenfield first described the microscopic characteristics of Hodgkin's lymphoma in 1872 and 1878, respectively.[40] In 1898 and 1902, respectively, Carl Sternberg and Dorothy Reed independently described the cytogenetic features of the malignant cells of Hodgkin's lymphoma, now called Reed–Sternberg cells.[40]

Tissue specimens from Hodgkin's seven patients remained at Guy's Hospital for a number of years. Nearly 100 years after Hodgkin's initial publication, histopathologic reexamination confirmed Hodgkin's lymphoma in only three of seven of these patients.[42] The remaining cases included non-Hodgkin lymphoma, tuberculosis, and syphilis.[42]

Hodgkin's lymphoma was one of the first cancers which could be treated using radiation therapy and, later, it was one of the first to be treated by combination chemotherapy.

Notable cases

- James Conner, running back and 2014 ACC Player of the Year for the Pittsburgh Panthers.[43]

- Professional surfer Chris O'Rourke died May 26, 1981 [44]

- Howard Carter, Egyptologist and discoverer of the Tomb of Tutankhamun, died in 1939 from Hodgkin's disease.[45][46]

- Jiří Grossmann, Czechoslovak theatre actor, poet, and composer [47]

- Irish actor Richard Harris, who portrayed Albus Dumbledore in the first two Harry Potter movies, diagnosed in 2002, and died on October 25, 2002.[48]

- Flip Saunders, head coach of the NBA team Minnesota Timberwolves, announced in August 2015 that he was diagnosed with Hodgkin's disease. He later died of the disease in October 2015.[49]

- Eric Berry, All-Pro strong safety for the Kansas City Chiefs of the National Football League, diagnosed in 2014.[50]

- Starchild Abraham Cherrix, a teenager whose refusal to undergo further conventional treatment after relapsing in 2006 resulted in a court battle and a change to Virginia laws about medical neglect.[51]

- Michael Cuccione, a Canadian child actor was diagnosed in 1994 at age 9.[52]

- Victoria Duval, American tennis player was diagnosed in 2014.[53]

- Delta Goodrem, Australian singer, was diagnosed in 2003 after having finished filming of television show Neighbours.[54]

- Michael C. Hall (born February 1, 1971), American actor, best known for his lead role as Dexter Morgan, in Showtime's crime series Dexter. In 2010, aged 38, Hall announced he was undergoing treatment for Hodgkin's Lymphoma; within two years, the disease was in full remission.[55]

- Daniel Hauser, whose mother fled with him in 2009 in order to prevent him from undergoing chemotherapy.[56]

- Tessa James, Australian actress, was diagnosed in 2014.[57]

- Mario Lemieux, Hall of Fame NHL player, co-owner of the Pittsburgh Penguins and founder of the Mario Lemieux Foundation, diagnosed in 1993.[58]

- Dinu Lipatti (1917–1950), Romanian classical pianist and composer. Diagnosed in 1947, received cortisone treatment in 1949; died from a burst abscess on his one lung.[59]

- Anthony Rizzo, MLB All-Star first baseman for the Chicago Cubs, diagnosed in May 2008 while signed as a minor league player for the Red Sox.[60]

- Ethan Zohn, American professional soccer player and a winner of the Survivor reality TV series. Zohn was diagnosed twice (in 2009 and 2011).[61]

References

- 1 2 Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. (Dec 15, 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010.". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. OCLC 23245604. PMID 23245604.

- ↑ Bower, Mark; Waxman, Jonathan (2011). Lecture Notes: Oncology (2 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 195. ISBN 9781118293003.

- 1 2 3 "Adult Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment (PDQ®)–Patient Version". NCI. August 3, 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- 1 2 World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 2.4. ISBN 9283204298.

- 1 2 3 "SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Hodgkin Lymphoma". NCI. April 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ↑ "Adult Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment (PDQ®)–Patient Version". NCI. August 3, 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 Armitage JO (August 2010). "Early-stage Hodgkin's Lymphoma". N. Engl. J. Med. 363 (7): 653–62. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1003733. PMID 20818856.

- ↑ Ward, E; DeSantis, C; Robbins, A; Kohler, B; Jemal, A (2014). "Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014.". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 64 (2): 83–103. PMID 24488779.

- ↑ Global Burden of Disease Study 2013, Collaborators (22 August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet (London, England). 386 (9995): 743–800. PMID 26063472.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (10 January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet (London, England). 385 (9963): 117–71. PMID 25530442.

- 1 2 Hodgkin T (1832). "On some morbid experiences of the absorbent glands and spleen". Med Chir Trans. 17: 69–97.

- ↑ Bobrove AM (June 1983). "Alcohol-related pain and Hodgkin's disease". The Western Journal of Medicine. 138 (6): 874–5. PMC 1010854

. PMID 6613116.

. PMID 6613116. - 1 2 3 4 Page 242 in: John Kearsley (1998). Cancer: A Comprehensive Clinical Guide. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 90-5702-215-X.

- ↑ Portlock CS (July 2008). "Hodgkin Lymphoma". Merck Manual Professional. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ↑ Hodgon DC, Gospodarowicz MK (2007). "Clinical Evaluation and Staging of Hodgkin Lymphoma". In Hoppe RT, Mauch PT, Armitage JO, Diehl V, Weiss LM. Hodgkin’s disease (2nd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 123–132. ISBN 978-0-7817-6422-3.

- ↑ Hilson AJ (July 6, 1995). "Making Sense". The New England Journal of Medicine. 333 (1): 66–67. doi:10.1056/NEJM199507063330118. PMID 7777006.

- ↑ Audard V, Zhang SY, Copie-Bergman C, Rucker-Martin C, Ory V, Candelier M, Baia M, Lang P, Pawlak A, Sahali D (May 2010). "Occurrence of minimal change nephrotic syndrome in classical Hodgkin lymphoma is closely related to the induction of c-mip in Hodgkin-Reed Sternberg cells and podocytes.". Blood. 115 (18): 3756–62. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-11-251132. PMC 2890576

. PMID 20200355.

. PMID 20200355. - 1 2 "HMDS: Hodgkin's Lymphoma". Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- ↑ Küppers R, Schwering I, Bräuninger A, Rajewsky K, Hansmann ML (2002). "Biology of Hodgkin's lymphoma". Annals of Oncology. 13 Suppl 1: 11–8. doi:10.1093/annonc/13.S1.11. PMID 12078890.

- ↑ Bräuninger A, Schmitz R, Bechtel D, Renné C, Hansmann ML, Küppers R (April 2006). "Molecular biology of Hodgkin's and Reed–Sternberg cells in Hodgkin's lymphoma". Int. J. Cancer. 118 (8): 1853–61. doi:10.1002/ijc.21716. PMID 16385563.

- ↑ Tzankov A, Bourgau C, Kaiser A, Zimpfer A, Maurer R, Pileri SA, Went P, Dirnhofer S (December 2005). "Rare expression of T-cell markers in classical Hodgkin's lymphoma". Mod. Pathol. 18 (12): 1542–9. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800473. PMID 16056244.

- ↑ Lamprecht B, Kreher S, Anagnostopoulos I, Jöhrens K, Monteleone G, Jundt F, Stein H, Janz M, Dörken B, Mathas S (2008). "Aberrant expression of the Th2 cytokine IL-21 in Hodgkin lymphoma cells regulates STAT3 signaling and attracts Treg cells via regulation of MIP-3a". Blood. 112 (Oct 2008): 3339–3347. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-01-134783. PMID 18684866.

- ↑ Hofman MS, Smeeton NC, Rankin SC, Nunan T, O'Doherty MJ (2009). "Observer Variation in Interpreting 18F-FDG PET/CT Findings for Lymphoma Staging". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 50 (10): 1594–1597. doi:10.2967/jnumed.109.064121. PMID 19759113.

- ↑ Herbst C, Rehan FA, Skoetz N, Bohlius J, Brillant C, Schulz H, Monsef I, Specht L, Engert A (2011). "Chemotherapy alone versus chemotherapy plus radiotherapy for early stage Hodgkin lymphoma". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD007110. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007110.pub2. PMID 21328291.

- ↑ Gobbi PG, Levis A, Chisesi T, Broglia C, Vitolo U, Stelitano C, Pavone V, Cavanna L, Santini G, Merli F, Liberati M, Baldini L, Deliliers GL, Angelucci E, Bordonaro R, Federico M (2005). "ABVD versus modified stanford V versus MOPPEBVCAD with optional and limited radiotherapy in intermediate- and advanced-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma: final results of a multicenter randomised trial by the Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi". J. Clin. Oncol. 23 (36): 9198–207. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.02.907. PMID 16172458.

- ↑ Edwards-Bennett SM, Jacks LM, Moskowitz CH, Wu EJ, Zhang Z, Noy A, Portlock CS, Straus DJ, Zelenetz AD, Yahalom J (March 2010). "Stanford V program for locally extensive and advanced Hodgkin lymphoma: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience". Annals of Oncology. 21 (3): 574–81. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdp337. PMID 19759185.

- ↑ "Home | German Hodgkin Study Group". Ghsg.org. Retrieved 2012-08-26.

- ↑ Saini KS, Azim HA, Cocorocchio E, Vanazzi A, Saini ML, Raviele PR, Pruneri G, Peccatori FA (2011). "Rituximab in Hodgkin lymphoma: Is the target always a hit?". Cancer Treat Rev. 37 (5): 385–90. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.11.005. PMID 21183282.

- ↑ Klimm B, Diehl V, Engert A (2007). "Hodgkin's Lymphoma in the Elderly: A Different Disease in Patients Over 60". Oncology. 21 (8): 982–90; discussion 990, 996, 998 passim. PMID 17715698.

- ↑ "RTanswers.com". RTanswers.com. 2010-12-03. Retrieved 2012-08-26.

- ↑ van Dorp W, van Beek RD, Laven JS, Pieters R, de Muinck Keizer-Schrama SM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM (2011). "Long-term endocrine side effects of childhood Hodgkin's lymphoma treatment: A review". Human Reproduction Update. 18 (1): 12–28. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr038. PMID 21896559.

- ↑ Fermé C, Eghbali H, Meerwaldt JH, Rieux C, Bosq J, Berger F, Girinsky T, Brice P, van't Veer MB, Walewski JA, Lederlin P, Tirelli U, Carde P, Van den Neste E, Gyan E, Monconduit M, Diviné M, Raemaekers JM, Salles G, Noordijk EM, Creemers GJ, Gabarre J, Hagenbeek A, Reman O, Blanc M, Thomas J, Vié B, Kluin-Nelemans JC, Viseu F, Baars JW, Poortmans P, Lugtenburg PJ, Carrie C, Jaubert J, Henry-Amar M (November 2007). "Chemotherapy plus involved-field radiation in early-stage Hodgkin's disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (19): 1916–27. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa064601. PMID 17989384.

- ↑ Hasenclever D, Diehl V (November 19, 1998). "A Prognostic Score for Advanced Hodgkin's Disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 339 (21): 1506–14. doi:10.1056/NEJM199811193392104. PMID 9819449.

- 1 2 Biggi A, Gallamini A, Chauvie S, Hutchings M, Kostakoglu L, Gregianin M, Meignan M, Malkowski B, Hofman MS, Barrington SF (2013). "International Validation Study for Interim PET in ABVD-Treated, Advanced-Stage Hodgkin Lymphoma: Interpretation Criteria and Concordance Rate Among Reviewers". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 54 (5): 683–690. doi:10.2967/jnumed.112.110890. PMID 23516309.

- ↑ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organisation. 2009. Retrieved Nov 11, 2009.

- ↑ Mauch, Peter; James Armitage; Volker Diehl; Richard Hoppe; Laurence Weiss (1999). Hodgkin's Disease. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 62–64. ISBN 0-7817-1502-4.

- ↑ "SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Leukemia". NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ↑ Biggar RJ, Jaffe ES, Goedert JJ, Chaturvedi A, Pfeiffer R, Engels EA (2006). "Hodgkin lymphoma and immunodeficiency in persons with HIV/AIDS". Blood. 108 (12): 3786–91. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-05-024109. PMC 1895473

. PMID 16917006.

. PMID 16917006. - ↑ "Hodgkin lymphoma statistics". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hellman S (2007). "Brief Consideration of Thomas Hodgkin and His Times". In Hoppe RT, Mauch PT, Armitage JO, Diehl V, Weiss LM. Hodgkin Lymphoma (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 3–6. ISBN 0-7817-6422-X.

- ↑ Dawson PJ (December 1999). "The original illustrations of Hodgkin's disease". Annals of Diagnostic Pathology. 3 (6): 386–93. doi:10.1016/S1092-9134(99)80018-5. PMID 10594291.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Geller SA (August 1984). "Comments on the anniversary of the description of Hodgkin's disease". Journal of the National Medical Association. 76 (8): 815–7. PMC 2609834

. PMID 6381744.

. PMID 6381744. - ↑ "James Conner Announces Cancer Diagnosis".

- ↑ http://www.surfermag.com/features/a-life-cut-short/#Mk5YkzfcxDueWglg.97

- ↑ James, T. G. H. (2012). Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun. [2001]. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 454–5. ISBN 9781845112585.

- ↑ James, TGH (2004). "Carter, Howard (1874–1939)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32312.

- ↑ Skálová, Johana. Nevyjasněná úmrtí V. 1st Ed. Praha : The World Circle Foundation, 2000. ISBN 80-902731-7-3.

- ↑ "Lionhearted—Death, Richard Harris". People.com. Retrieved 2015-03-04.

- ↑ |"Minnesota Timberwolves Say Head Coach Flip Saunders Has Died". abc.go.com. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ↑ "Eric Berry has Hodgkin's lymphoma". ESPN.com.

- ↑ "Teen, court reach agreement over cancer care". MSNBC. Associated Press. September 5, 2006. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ↑ "Childhood Cancer Research Program—Michael Cuccione Foundation—Helping Babies, Children, Kids with Cancer—Childhood Cancer". www.childhoodcancerresearch.org. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- ↑ "Victoria Duval battling cancer".

- ↑ "Doctors said all I needed was rest—in fact cancer was slowly killing me, says Delta Goodrem". Daily Mail. 2007-06-05. Retrieved 2015-03-04.

- ↑ Huver, Scott (2010-07-23). "Cancer-Free Michael C. Hall Back to Work on Dexter—Health, Dexter, Michael C. Hall". People. Retrieved 2015-03-04.

- ↑ "Minnesota: Evaluation Ordered for a 13-Year-Old With Cancer". The New York Times. Associated Press. May 16, 2009. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ↑ "Tessa James reveals she is in remission". au.news.yahoo.com. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ↑ "Mario Lemieux Foundation". Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ↑ Mark Ainley (2002). "Dinu Lipatti: Prince of Pianists". markainley.com. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ↑ "Emma: Anthony Rizzo's Indelible Impact". CBS Chicago. 8 May 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ↑ "Ethan Zohn is a survivor in more ways than one". tribunedigital-chicagotribune. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

Further reading

- Charlotte DeCroes Jacobs. Henry Kaplan and the Story of Hodgkin's Disease (Stanford University Press; 2010) 456 pages; combines a biography of the American radiation oncologist (1918–84) with a history of the lymphatic cancer whose treatment he helped to transform.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hodgkin's lymphoma. |

| Wikinews has related news: |

- Hodgkin's lymphoma at DMOZ

- Hodgkin Disease at American Cancer Society

- Hodgkin's Lymphoma at the American National Cancer Institute

- Clinically reviewed Hodgkin's lymphoma information for patients, from Cancer Research UK