Epstein–Barr virus

| Epstein–Barr | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Two Epstein–Barr virions | |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group I (dsDNA) |

| Order: | Herpesvirales |

| Family: | Herpesviridae |

| Subfamily: | Gammaherpesvirinae |

| Genus: | Lymphocryptovirus |

| Species: | Human herpesvirus 4 (HHV-4) |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), also called human herpesvirus 4 (HHV-4), is one of eight known viruses in the herpes family, and is one of the most common viruses in humans.

It is best known as the cause of infectious mononucleosis (glandular fever). It is also associated with particular forms of cancer, such as Hodgkin's lymphoma, Burkitt's lymphoma, gastric cancer, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and conditions associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), such as hairy leukoplakia and central nervous system lymphomas.[1][2] There is evidence that infection with EBV is associated with a higher risk of certain autoimmune diseases,[3] especially dermatomyositis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren's syndrome,[4][5] and multiple sclerosis.[6] Some 200,000 cancer cases per year are thought to be attributable to EBV.[7]

Infection with EBV occurs by the oral transfer of saliva[8] and genital secretions.

Most people become infected with EBV and gain adaptive immunity. In the United States, about half of all five-year-old children and about 90 percent of adults have evidence of previous infection.[9] Infants become susceptible to EBV as soon as maternal antibody protection disappears. Many children become infected with EBV, and these infections usually cause no symptoms or are indistinguishable from the other mild, brief illnesses of childhood. In the United States and other developed countries, many people are not infected with EBV in their childhood years. When infection with EBV occurs during adolescence, it causes infectious mononucleosis 35 to 50 percent of the time.[10]

EBV infects B cells of the immune system and epithelial cells. Once EBV's initial lytic infection is brought under control, EBV latency persists in the individual's B cells for the rest of the individual's life.[8]

Symptoms

As previously stated there are few or no symptoms noticeable when a person contracts EBV at the adolescence stage of life but when EBV is contracted as an adult it may cause; fatigue, fever, inflamed throat, swollen lymph nodes in the neck, enlarged spleen, swollen liver, rash[11]

Virology

Structure and genome

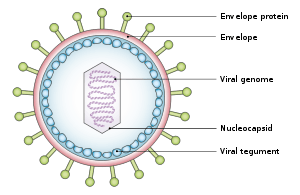

The virus is approximately 122 nm to 180 nm in diameter and is composed of a double helix of DNA of about 172,000 base pairs and containing about 85 genes.[8] The DNA is surrounded by a protein nucleocapsid. This nucleocapsid is surrounded by a tegument made of protein, which in turn is surrounded by an envelope containing both lipids[12] and surface projections of glycoproteins which are essential to infection of the host cell.[12]

Tropism

The term viral tropism refers to which cell types EBV infects. EBV can infect different cell types, including B cells and epithelial cells.[13]

The viral three-part glycoprotein complexes of gHgLgp42 mediate B cell membrane fusion; although the two-part complexes of gHgL mediate epithelial cell membrane fusion. EBV that are made in the B cells have low numbers of gHgLgp42 complexes, because these three-part complexes interact with Human-leukocyte-antigen class II molecules present in B cells in the endoplasmic reticulum and are degraded. In contrast, EBV from epithelial cells are rich in the three-part complexes because these cells do not normally contain HLA class II molecules. As a consequence, EBV made from B cells are more infectious to epithelial cells, and EBV made from epithelial cells are more infectious to B cells. Viruses lacking the gp42 portion are able to bind to human B cells but unable to infect.[14]

Replication cycle

Entry to the cell

EBV can infect both B cells and epithelial cells. The mechanisms for entering these two cells are different.

To enter B cells, viral glycoprotein gp350 binds to cellular receptor CD21 (also known as CR2).[15] Then, viral glycoprotein gp42 interacts with cellular MHC class II molecules. This triggers fusion of the viral envelope with the cell membrane, allowing EBV to enter the B cell.[12] Human CD35, also known as complement receptor 1 (CR1), is an additional attachment factor for gp350/220, and can provide a route for entry of EBV into CD21-negative cells, including immature B-cells. EBV infection downregulates expression of CD35.[16]

To enter epithelial cells, viral protein BMRF-2 interacts with cellular β1 integrins. Then, viral protein gH/gL interacts with cellular αvβ6/αvβ8 integrins. This triggers fusion of the viral envelope with the epithelial cell membrane, allowing EBV to enter the epithelial cell.[12] Unlike B cell entry, epithelial cell entry is actually impeded by viral glycoprotein gp42.[15]

Once EBV enters the cell, the viral capsid dissolves and the viral genome is transported to the cell nucleus.

Lytic replication

The lytic cycle, or productive infection, results in the production of infectious virions. EBV can undergo lytic replication in both B cells and epithelial cells. In B cells, lytic replication normally only takes place after reactivation from latency. In epithelial cells, lytic replication often directly follows viral entry.[12]

For lytic replication to occur, the viral genome must be linear. The latent EBV genome is circular, so it must linearize in the process of lytic reactivation. During lytic replication, viral DNA polymerase is responsible for copying the viral genome. This contrasts with latency, in which host cell DNA polymerase copies the viral genome.[12]

Lytic gene products are produced in three consecutive stages: immediate-early, early, and late.[12] Immediate-early lytic gene products act as transactivators, enhancing the expression of later lytic genes. Immediate-early lytic gene products include BZLF1 (also known as Zta, EB1, associated with its product gene ZEBRA) and BRLF1 (associated with its product gene Rta).[12] Early lytic gene products have many more functions, such as replication, metabolism, and blockade of antigen processing. Early lytic gene products include BNLF2.[12] Finally, late lytic gene products tend to be proteins with structural roles, like VCA, which forms the viral capsid. Other late lytic gene products, such as BCRF1, help EBV evade the immune system.[12]

EGCG, a polyphenol in green tea, has shown in a study to inhibit EBV spontaneous lytic infection at the DNA, gene transcription and protein levels in a time and dose-dependent manner; the expression of EBV lytic genes Zta, Rta, and early antigen complex EA-D (induced by Rta), however the highly stable EBNA-1 gene found across all stages of EBV infection is unaffected.[17] Specific inhibitors (to the pathways) suggest that Ras/MEK/MAPK pathway contributes to EBV lytic infection though BZLF1 and PI3-K pathway through BRLF1, the latter completely abrogating the ability of a BRLF1 adenovirus vector to induce the lytic form of EBV infection.[17] Additionally, the activation of some genes but not others is being studied to determine just how to induce immune destruction of latently infected B-cells by use of either TPA or sodium butyrate.[17]

Unlike lytic replication for many other viruses, EBV lytic replication does not inevitably lead to lysis of the host cell because EBV virions are produced by budding from the infected cell. Lytic proteins include gp350 and gp110.[12][18]

Latency

Unlike lytic replication, latency does not result in production of virions.[12] Instead, the EBV genome circular DNA resides in the cell nucleus as an episome and is copied by cellular DNA polymerase.[12] In latency, only a portion of EBV's genes are expressed.[8] Latent EBV expresses its genes in one of three patterns, known as latency programs. EBV can latently persist within B cells and epithelial cells, but different latency programs are possible in the two types of cell.

EBV can exhibit one of three latency programs: Latency I, Latency II, or Latency III. Each latency program leads to the production of a limited, distinct set of viral proteins and viral RNAs.[19][20]

| Gene Expressed | EBNA-1 | EBNA-2 | EBNA-3A | EBNA-3B | EBNA-3C | EBNA-LP | LMP-1 | LMP-2A | LMP-2B | EBER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product | Protein | Protein | Protein | Protein | Protein | Protein | Protein | Protein | Protein | ncRNAs |

| Latency I | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + |

| Latency II | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | + |

| Latency III | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

It is also postulated that a program exists in which all viral protein expression is shut off (Latency 0).

Within B cells, all three latency programs are possible.[8] EBV latency within B cells usually progresses from Latency III to Latency II to Latency I. Each stage of latency uniquely influences B cell behavior.[8] Upon infecting a resting naive B cell, EBV enters Latency III. The set of proteins and RNAs produced in Latency III transforms the B cell into a proliferating blast (also known as B cell activation).[8][12] Later, the virus restricts its gene expression and enters Latency II. The more limited set of proteins and RNAs produced in Latency II induces the B cell to differentiate into a memory B cell.[8][12] Finally, EBV restricts gene expression even further and enters Latency I. Expression of EBNA-1 allows the EBV genome to replicate when the memory B cell divides.[8][12]

Within epithelial cells, only Latency II is possible.

In primary infection, EBV replicates in oro-pharyngeal epithelial cells and establishes Latency III, II, and I infections in B-lymphocytes. EBV latent infection of B-lymphocytes is necessary for virus persistence, subsequent replication in epithelial cells, and release of infectious virus into saliva. EBV Latency III and II infections of B-lymphocytes, Latency II infection of oral epithelial cells, and Latency II infection of NK- or T-cell can result in malignancies, marked by uniform EBV genome presence and gene expression.[21]

Reactivation

Latent EBV in B cells can be reactivated to switch to lytic replication. This is known to happen in vivo, but what triggers it is not known precisely. In vitro, latent EBV in B cells can be reactivated by stimulating the B cell receptor, so reactivation in vivo probably takes place when latently infected B cells respond to unrelated infections.[12] In vitro, latent EBV in B cells can also be reactivated by treating the cells with sodium butyrate or TPA.

Transformation of B-lymphocytes

When EBV infects B cells in vitro, lymphoblastoid cell lines eventually emerge that are capable of indefinite growth. The growth transformation of these cell lines is the consequence of viral protein expression.

EBNA-2, EBNA-3C and LMP-1 are essential for transformation, whereas EBNA-LP and the EBERs are not.[22]

It is postulated that following natural infection with EBV, the virus executes some or all of its repertoire of gene expression programs to establish a persistent infection. Given the initial absence of host immunity, the lytic cycle produces large amounts of virus to infect other (presumably) B-lymphocytes within the host.

The latent programs reprogram and subvert infected B-lymphocytes to proliferate and bring infected cells to the sites at which the virus presumably persists. Eventually, when host immunity develops, the virus persists by turning off most (or possibly all) of its genes, only occasionally reactivating to produce fresh virions. A balance is eventually struck between occasional viral reactivation and host immune surveillance removing cells that activate viral gene expression.

The site of persistence of EBV may be bone marrow. EBV-positive patients who have had their own bone marrow replaced with bone marrow from an EBV-negative donor are found to be EBV-negative after transplantation.[23]

Latent antigens

All EBV nuclear proteins are produced by alternative splicing of a transcript starting at either the Cp or Wp promoters at the left end of the genome (in the conventional nomenclature). The genes are ordered EBNA-LP/EBNA-2/EBNA-3A/EBNA-3B/EBNA-3C/EBNA-1 within the genome.

The initiation codon of the EBNA-LP coding region is created by an alternate splice of the nuclear protein transcript. In the absence of this initiation codon, EBNA-2/EBNA-3A/EBNA-3B/EBNA-3C/EBNA-1 will be expressed depending on which of these genes is alternatively spliced into the transcript.

Protein/genes

| Protein/gene/antigen | Stage | Description |

|---|---|---|

| EBNA-1 | latent+lytic | EBNA-1 protein binds to a replication origin (oriP) within the viral genome and mediates replication and partitioning of the episome during division of the host cell. It is the only viral protein expressed during group I latency. |

| EBNA-2 | latent+lytic | EBNA-2 is the main viral transactivator. |

| EBNA-3 | latent+lytic | These genes also bind the host RBP-Jκ protein. |

| LMP-1 | latent | LMP-1 is a six-span transmembrane protein that is also essential for EBV-mediated growth transformation. |

| LMP-2 | latent | LMP-2A/LMP-2B are transmembrane proteins that act to block tyrosine kinase signaling. |

| EBER | latent | EBER-1/EBER-2 are small nuclear RNAs, which bind to certain nucleoprotein particles, enabling binding to PKR (dsRNA dependent serin/threonin protein kinase) thus inhibiting its function. EBER-particles also induce the production of IL-10, which enhances growth and inhibits cytotoxic T-cells. |

| v-snoRNA1 | latent | Epstein–Barr virus snoRNA1 is a box CD-snoRNA generated by the virus during latency. V-snoRNA1 may act as a miRNA-like precursor that is processed into 24 nucleotide sized RNA fragments that target the 3'UTR of viral DNA polymerase mRNA.[24] |

| ebv-sisRNA | latent | Ebv-sisRNA-1 is a stable intronic sequence RNA generated during latency program III. After the EBERs it is the third most abundant small RNA produced by the virus during this program.[25] |

| miRNAs | latent | EBV microRNAs are encoded by two transcripts, one set in the BART gene and one set near the BHRF1 cluster. The three BHRF1 miRNAS are expressed during type III latency, whereas the large cluster of BART miRNAs (up to 20 miRNAs) are expressed during type II latency. The functions of these miRNAs are currently unknown. |

| EBV-EA | lytic | early antigen |

| EBV-MA | lytic | membrane antigen |

| EBV-VCA | lytic | viral capsid antigen |

| EBV-AN | lytic | alkaline nuclease[26] |

Subtypes of EBV

EBV can be divided into two major types, EBV type 1 and EBV type 2. These two subtypes have different EBNA-3 genes. As a result, the two subtypes differ in their transforming capabilities and reactivation ability. Type 1 is dominant throughout most of the world, but the two types are equally prevalent in Africa. One can distinguish EBV type 1 from EBV type 2 by cutting the viral genome with a restriction enzyme and comparing the resulting digestion patterns by gel electrophoresis.[12]

Role in disease

EBV has been implicated in several diseases that include infectious mononucleosis,[27] Burkitt's lymphoma,[28] Hodgkin's lymphoma,[29] gastric cancer,[30] nasopharyngeal carcinoma,[31] multiple sclerosis,[6][32] and lymphomatoid granulomatosis.[33] Additional diseases that have been linked to EBV include Gianotti–Crosti syndrome, erythema multiforme, acute genital ulcers, oral hairy leukoplakia.[34]

The Epstein–Barr virus has been implicated also in disorders related to alpha-synuclein aggregation (e.g. Parkinson's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and multiple system atrophy).[35]

History

The Epstein–Barr virus was named after Michael Anthony Epstein (born 18 May 1921), now a professor emeritus at the University of Bristol, and Yvonne Barr (born 1932), a 1966 Ph.D graduate from the University of London, who together discovered[36] and, in 1964, published on the existence of the virus.[37] In 1961, Epstein, a pathologist and expert electron microscopist, attended a lecture on "The Commonest Children's Cancer in Tropical Africa—A Hitherto Unrecognised Syndrome." This lecture, by Denis Parsons Burkitt, a surgeon practicing in Uganda, was the description of the "endemic variant" (pediatric form) of the disease that bears his name. In 1963, a specimen was sent from Uganda to Middlesex Hospital to be cultured. Virus particles were identified in the cultured cells, and the results were published in The Lancet in 1964 by Epstein, Bert Achong, and Barr. Cell lines were sent to Werner and Gertrude Henle at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia who developed serological markers. In 1967, a technician in their laboratory developed mononucleosis and they were able to compare a stored serum sample, showing that antibodies to the virus developed.[38][39][40] In 1968, they discovered that EBV can directly immortalize B cells after infection, mimicking some forms of EBV-related infections,[41] and confirmed the link between the virus and infectious mononucleosis.[42]

Research

As a relatively complex virus, EBV is not yet fully understood. Laboratories around the world continue to study the virus and develop new ways to treat the diseases it causes. One popular way of studying EBV in vitro is to use bacterial artificial chromosomes.[43] Epstein–Barr virus can be maintained and manipulated in the laboratory in continual latency (a property shared with Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, another of the eight human herpesviruses). Although many viruses are assumed to have this property during infection of their natural hosts, there is not an easily managed system for studying this part of the viral lifecycle. Genomic studies of EBV have been able to explore lytic reactivation and regulation of the latent viral episome.[44]

See also

- Epstein–Barr virus vaccine

- Epstein–Barr virus infection

- James Corson Niederman, the physician who proved how the Epstein–Barr virus is transmitted in infectious mononucleosis

- Transcriptome and epigenome of EBV

References

- ↑ Maeda E, Akahane M, Kiryu S, et al. (January 2009). "Spectrum of Epstein–Barr virus-related diseases: a pictorial review". Jpn J Radiol. 27 (1): 4–19. doi:10.1007/s11604-008-0291-2. PMID 19373526.

- ↑ Cherry-Peppers, G; Daniels, CO; Meeks, V; Sanders, CF; Reznik, D (February 2003). "Oral manifestations in the era of HAART.". Journal of the National Medical Association. 95 (2 Suppl 2): 21S–32S. PMC 2568277

. PMID 12656429.

. PMID 12656429. - ↑ Toussirot E, Roudier J (October 2008). "Epstein–Barr virus in autoimmune diseases". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 22 (5): 883–96. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2008.09.007. PMID 19028369.

- ↑ Dreyfus DH (December 2011). "Autoimmune disease: A role for new anti-viral therapies?". Autoimmunity Reviews. 11 (2): 88–97. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2011.08.005. PMID 21871974.

- ↑ Pender MP (2012). "CD8+ T-Cell Deficiency, Epstein–Barr Virus Infection, Vitamin D Deficiency, and Steps to Autoimmunity: A Unifying Hypothesis". Autoimmune Diseases. 2012: 189096. doi:10.1155/2012/189096. PMC 3270541

. PMID 22312480.

. PMID 22312480. - 1 2 Ascherio A, Munger KL (September 2010). "Epstein–Barr virus infection and multiple sclerosis: a review". Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 5 (3): 271–7. doi:10.1007/s11481-010-9201-3. PMID 20369303.

- ↑ http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-us/cancer-news/press-release/2014-03-24-developing-a-vaccine-for-the-epstein-barr-virus-could-prevent-up-to-200000-cancers-globally-say

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Amon, Wolfgang; Farrell (November 2004). "Reactivation of Epstein–Barr virus from latency". Reviews in Medical Virology. 15 (3): 149–56. doi:10.1002/rmv.456. PMID 15546128.

- ↑ About 90% of adults have antibodies that show that they have a current or past EBV infection. National Center for Infectious Diseases

- ↑ CDC. "Epstein–Barr Virus and Infectious Mononucleosis". CDC. Retrieved 2011-12-29.

- ↑ "About Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 14 Sept. 2016. Web. 23 Oct. 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Odumade, O. A.; Hogquist, Balfour (January 2011). "Progress and Problems in Understanding and Managing Primary Epstein–Barr Virus Infections". American Society for Microbiology. 24 (1): 193–209. doi:10.1128/CMR.00044-10. PMC 3021204

. PMID 21233512. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

. PMID 21233512. Retrieved 30 May 2012. - ↑ Shannon-Lowe, C; Rowe, M (2014). "Epstein Barr virus entry; kissing and conjugation". Current Opinion in Virology. 4: 78–84. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2013.12.001. PMID 24553068.

- ↑ Wang, X; Hutt-Fletcher, LM (1998). "Epstein-Barr virus lacking glycoprotein gp42 can bind to B cells but is not able to infect". J. Virol. 72: 158–63. PMC 109360

. PMID 9420211.

. PMID 9420211. - 1 2 "Entrez Gene: CR2 complement component (3d/Epstein Barr virus) receptor 2".

- ↑ Ogembo JG, Kannan L, Ghiran I, Nicholson-Weller A, Finberg RW, Tsokos GC, Fingeroth JD (2013). "Human complement receptor type 1/CD35 is an Epstein-Barr Virus receptor". Cell Rep. 3 (2): 371–385. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.023. PMC 3633082

. PMID 23416052.

. PMID 23416052. - 1 2 3 http://carcin.oxfordjournals.org/content/34/3/627.full

- ↑ Lockey TD, Zhan X, Surman S, Sample CE, Hurwitz JL (2008). "Epstein–Barr virus vaccine development: a lytic and latent protein cocktail". Front. Biosci. 13 (13): 5916–27. doi:10.2741/3126. PMID 18508632. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Calderwood MA, Venkatesan K, Xing L, Chase MR, Vazquez A, Holthaus AM, Ewence AE, Li N, Hirozane-Kishikawa T, Hill DE, Vidal M, Kieff E, Johannsen E (May 2007). "Epstein–Barr virus and virus human protein interaction maps". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (18): 7606–11. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702332104. PMC 1863443

. PMID 17446270. The nomenclature used here is that of Kieff. Other laboratories use different nomenclatures.

. PMID 17446270. The nomenclature used here is that of Kieff. Other laboratories use different nomenclatures. - ↑ Hutzinger R, Feederle R, Mrazek J, Schiefermeier N, Balwierz PJ, Zavolan M, Polacek N, Delecluse H, Hüttenhofer A (August 14, 2009). Cullen, Bryan R., ed. "Expression and Processing of a Small Nucleolar RNA from the Epstein–Barr Virus Genome". PLoS Pathogens. 5 (8): e1000547. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000547. PMC 2718842

. PMID 19680535.

. PMID 19680535. - ↑ Robertson, ES (editor) (2010). Epstein–Barr Virus: Latency and Transformation. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-62-2.

- ↑ Yates JL, Warren N, Sugden B (1985). "Stable replication of plasmids derived from Epstein–Barr virus in various mammalian cells". Nature. 313 (6005): 812–5. doi:10.1038/313812a0. PMID 2983224.

- ↑ Gratama JW, Oosterveer MA, Zwaan FE, Lepoutre J, Klein G, Ernberg I (1988). "Eradication of Epstein–Barr virus by allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: implications for sites of viral latency". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85 (22): 8693–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.22.8693. PMC 282526

. PMID 2847171.

. PMID 2847171. - ↑ Hutzinger, R.; Feederle, R.; Mrazek, J.; Schiefermeier, N.; Balwierz, J.; Zavolan, M.; Polacek, N.; Delecluse, J.; Hüttenhofer, A. (Aug 2009). Cullen, Bryan R, ed. "Expression and processing of a small nucleolar RNA from the Epstein-Barr virus genome" (Free full text). PLoS Pathogens. 5 (8): e1000547. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000547. ISSN 1553-7366. PMC 2718842

. PMID 19680535.

. PMID 19680535. - ↑ Moss WN, Steitz JA (August 2013). "Genome-wide analyses of Epstein-Barr virus reveal conserved RNA structures and a novel stable intronic sequence RNA". BMC Genomics. 14: 543. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-14-543. PMC 3751371

. PMID 23937650.

. PMID 23937650. - ↑ Buisson M, Géoui T, Flot D, Tarbouriech N, Ressing ME, Wiertz EJ, Burmeister WP (2009). "A bridge crosses the active-site canyon of the Epstein–Barr virus nuclease with DNase and RNase activities". J Mol. Biol. 391 (4): 717–28. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.034. PMID 19538972.

- ↑ Weiss, LM; O'Malley, D (2013). "Benign lymphadenopathies". Modern Pathology. 26 (Supplement 1): S88–S96. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2012.176. PMID 23281438.

- ↑ Pannone, Giuseppe; Zamparese, Rosanna; Pace, Mirella; Pedicillo, Maria; Cagiano, Simona; Somma, Pasquale; Errico, Maria; Donofrio, Vittoria; Franco, Renato; De Chiara, Annarosaria; Aquino, Gabriella; Bucci, Paolo; Bucci, Eduardo; Santoro, Angela; Bufo, Pantaleo (2014). "The role of EBV in the pathogenesis of Burkitt's Lymphoma: an Italian hospital based survey". Infectious Agents and Cancer. 9 (1): 34. doi:10.1186/1750-9378-9-34. ISSN 1750-9378.

- ↑ Gandhi, MK (May 2004). "Epstein-Barr virus-associated Hodgkin's lymphoma". Br J Haematol. 125 (3): 267–81. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04902.x. PMID 15086409.

- ↑ "Developing a vaccine for the Epstein-Barr Virus could prevent up to 200,000 cancers globally say experts".

- ↑ Dogan, S; Hedberg, ML; Ferris, RL; Rath, TJ; Assaad, AM; Chiosea, SI (April 2014). "Human papillomavirus and Epstein-Barr virus in nasopharyngeal carcinoma in a low-incidence population.". Head & neck. 36 (4): 511–6. doi:10.1002/hed.23318. PMC 4656191

. PMID 23780921.

. PMID 23780921. - ↑ Mechelli R, Manzari C, Policano C, Annese A, Picardi E, Umeton R, Fornasiero A, D'Erchia AM, Buscarinu MC, Agliardi C, Annibali V, Serafini B, Rosicarelli B, Romano S, Angelini DF, Ricigliano VA, Buttari F, Battistini L, Centonze D, Guerini FR, D'Alfonso S, Pesole G, Salvetti M, Ristori G (Mar 31, 2015). "Epstein-Barr virus genetic variants are associated with multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 84 (13): 1362–8. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001420. PMC 4388746

. PMID 25740864.

. PMID 25740864. - ↑ Tagliavini, E.; Rossi, G.; Valli, R.; Zanelli, M.; Cadioli, A.; Mengoli, M. C.; Bisagni, A.; Cavazza, A.; Gardini, G. (August 2013). "Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: a practical review for pathologists dealing with this rare pulmonary lymphoproliferative process". Pathologica. 105 (4): 111–116. PMID 24466760.

- ↑ Di Lernia, Vito; Mansouri, Yasaman (2013-10-01). "Epstein-Barr virus and skin manifestations in childhood". International Journal of Dermatology. 52 (10): 1177–1184. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05855.x. ISSN 1365-4632. PMID 24073903.

- ↑ Woulfe J, Hoogendoorn H, Tarnopolsky M, Muñoz DG (Nov 14, 2000). "Monoclonal antibodies against Epstein-Barr virus cross-react with alpha-synuclein in human brain". Neurology. 55 (9): 1398–401. doi:10.1212/WNL.55.9.1398. PMID 11087792.

- ↑ McGrath, Paula (6 April 2014). "Cancer virus discovery helped by delayed flight". BBC News, Health. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ↑ Epstein, M. A.; Achong, B. G.; Barr, Y. M. (1964). "Virus particles in cultured lymphoblasts from Burkitt's lymphoma". The Lancet. 1: 702–703.

- ↑ Epstein, M. Anthony (2005). "1. The origins of EBV research: discovery and characterization of the virus". In Robertson, Earl S. Epstein–Barr Virus. Trowbridge: Cromwell Press. pp. 1–14. ISBN 1-904455-03-4. Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- ↑ Erle S. Robertson (2005). Epstein-Barr Virus. Horizon Scientific Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-904455-03-5. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ↑ Miller, George (December 21, 2006). "Book Review: Epstein–Barr Virus". New England Journal of Medicine. 355 (25): 2708–2709. doi:10.1056/NEJMbkrev39523.

- ↑ Henle W, Henle G (1980). "Epidemiologic aspects of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-associated diseases". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 354: 326–31. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb27975.x. PMID 6261650.

- ↑ Young, LS (2009). Desk Encyclopedia of Human and Medical Virology. Boston: Academic Press. pp. 532–533.

- ↑ Delecluse HJ, Feederle R, Behrends U, Mautner J (December 2008). "Contribution of viral recombinants to the study of the immune response against the Epstein–Barr virus". Seminars in Cancer Biology. 18 (6): 409–15. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.09.001. PMID 18938248.

- ↑ Arvey A, Tempera I, Tsai K, Chen HS, Tikhmyanova N, Klichinsky M, Leslie C, Lieberman PM (August 2012). "An atlas of the Epstein–Barr virus transcriptome and epigenome reveals host-virus regulatory interactions". Cell Host Microbe. 12 (2): 233–245. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.008. PMC 3424516

. PMID 22901543.

. PMID 22901543.

- "Human herpesvirus 4". NCBI Taxonomy Browser. 10376.