Hugo van der Goes

Hugo van der Goes (probably Ghent c. 1430/1440 – Auderghem 1482) was one of the most important Flemish painters of the late 15th century, along with Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, Hans Memling and Dieric Bouts. He introduced important innovations such as a new monumentalism, a specific colour spectrum and an individualistic manner of portraiture. The presence of his masterpiece, the Portinari Triptych in Florence, from the late-15th century onwards played a role in the development of realism in Italian Renaissance art.[1]

Life

Hugo van der Goes was likely born in Ghent or its environs around 1440.[1] Nothing is known with certainty about the artist's life prior to 1467, when he became a master in the painters' guild in Ghent. The sponsors for his membership of the guild were Joos van Wassenhove, master painter in Ghent from 1464, and Daneel Ruthaert.[2] It is likely that he had trained elsewhere before he became a master in Ghent. Some historians have suggested that Dieric Bouts was possibly the master of van der Goes but there is no independent evidence for this.[3]

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

In 1468 the artist was commissioned by the city of Ghent to execute some works in connection with the grant of the Great Indulgence of the city. In the following years, van der Goes created further decorations such as papal blazons at the behest of the city. In 1468 he was in the town of Bruges making decorations to celebrate the marriage between Charles the Bold and Margaret of York. On 18 October 1468 van der Goes and other members of the painter's guild invited painters from Tournai to their assembly in Ghent on the occasion of St. Luke's day. St. Luke was the patron saint of painters.

In 1469 Hugo van der Goes and Joos van Wassenhove vouched for Alexander Bening for his entry as a master in the Ghent painter's guild. In 1480 Alexander Bening married Catherina van der Goes, a cousin of Hugo van der Goes. Van der Goes and his workshop worked on commissions of the city of Ghent to provide heraldic decorations for Charles the Bold's Joyous Entry in Ghent in 1469 and later in 1472.

When in 1470 Joos van Wassenhove left Ghent for Italy to work in the service of Federico da Montefeltro, the Duke of Urbino, van der Goes became the leading painter in Ghent. In 1473 the Burgundian court paid van der Goes for the paintings and blazons on the occasion of Charles the Good's funeral. The painter was repeatedly elected as deacon of the Ghent painter's guild and served as its deacon from 1474 to 1476.

In this period, van der Goes painted the Adoration of the Magi (also referred to as the Monforte Altarpiece (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin)) and worked in the service of Tommaso Portinari on the monumental Portinari Altarpiece (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence) which arrived in Florence only in 1483, after the death of the artist.

Van der Goes achieved considerable success and secured important commissions from the Burgundian court, church institutions, affluent Flemish bourgeoisie and Italian business associations that were located in the Burgundian Low Countries.[1] At the highpoint of his career, van der Goes closed up his studio in Ghent in 1477 to become a frater conversus (i.e. a lay brother) at the monastic community of the Rood Klooster (or Rooklooster) near Auderghem (now in Brussels).[4] The Rood Klooster was part of the monastic wing of the Modern Devotion movement and belonged to the Windesheim Congregation. At the monastery he enjoyed certain privileges. He was allowed to continue working on painting commissions and to drink wine. According to the chronicle written up in Latin some time between 1509-1513 by Gaspar Ofhuys, a fellow monk in the Rood Klooster, van der Goes received visits by eminent persons including Archduke Maximillian.[4]

During his time at the cloister he was appointed in 1482 by the City of Leuven to assess the unfinished works of Dieric Bouts for the Leuven city hall. From the city administration he received a jug of Rhine wine for this service. Van der Goes probably also completed Bouts' unfinished Triptych for Hyppolite Berthoz. On the left panel he painted the patron portraits of the couple. In 1482 van der Goes was sent on a trip to Cologne together with his half-brother Nicolaes who had also taken religious vows and another brother of the monastery.[4] On the return trip from this visit to Cologne he was struck by an acute depression and declared himself to be damned.[5] He tried to kill himself unsuccessfully. His entourage decided to take him to Brussels and from there to the Rood Klooster.[1] After first making a brief recovery, he died not long thereafter in the Rood Klooster.[4]

There is speculation that anxiety about his artistic achievements may have contributed to his madness, for 'he was deeply troubled by the thought of how he would ever finish the works of art he had to paint, and it was said then that nine years would scarcely suffice'.[2] A report by a German physician, Hieronymus Münzer, from 1495, according to which a painter from Ghent was driven to melancholy by the attempt to equal the Ghent Altarpiece, may refer to Hugo van der Goes.[6]

The mental breakdown of Hugo van der Goes was only rediscovered in 1863, when the Belgian historian Alphonse Wauters published the information, which he had found in Ofhuys' newly discovered chronicle. Wauters' publication inspired the late Romantic Belgian painter Emile Wauters (a nephew of Alphonse Wauters) to create his 1872 painting Portrait of Hugo van der Goes (1872, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium). This painting depicts Hugo van der Goes during his period of madness and was so successful that it was awarded a Grand Medal at the Paris salon. In 1873 the Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh referred to this painting in a letter to his brother Theo van Gogh. On two further occasions van Gogh likened his own appearance to that of Hugo's recreated by Wauters, and stated that he identified emotionally with the 15th-century painter.[7]

Work

General

The majority of the original works of van der Goes has been lost and only survives through the numerous later copies after the lost originals. The large number of copies bears witness to the high regard in which he was held and also contributed to his important influence on early Flemish art. Martin Schongauer's prints after van der Goes' works spread the influence across the Flemish borders into Germany. The prominent Bruges painter Gerard David and the members of his workshop were clearly inspired by the Ghent artist.[1]

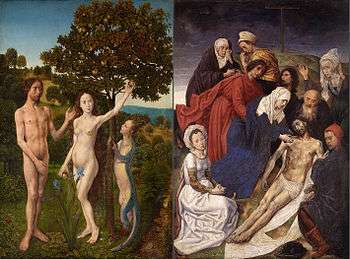

Hugo van der Goes was an important painter of altarpieces as well as portraits. His principal religious works include the Portinari Triptych (Uffizi, Florence), the Adoration of the Shepherds, the Adoration of the Magi (also called Monforte Altarpiece) (both Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), the Fall and Redemption of Man (Kunsthistorisches Museum) and the Death of the Virgin (Groeningemuseum, Bruges).[8]

The Portinari Triptych

Van der Goes' most famous surviving work is the Portinari Triptych (Uffizi, Florence). The Triptych is an altarpiece commissioned for the church of San Egidio in the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence by Tommaso Portinari, the manager of the Bruges branch of the Medici Bank.[9]

In 1483, apparently some years after its completion by van der Goes, the Portinari Altarpiece arrived in Pisa and was transported via canal to the Porta San Friano in Florence. The altarpiece was erected in Santa Maria Nuova.

The raw physiognomy of the shepherds made an impression upon the painters from Florence. Domenico Ghirlandaio was inspired by Hugo van der Goes for his Epiphany in the Sasseti chapel.[1] The largest Netherlandish work that could be seen in Florence, it was greatly praised. In his Vite of 1550 Giorgio Vasari referred to it as by "Ugo d'Anversa" ("Hugo of Antwerp"). This is the sole documentation for its authorship by Hugo van der Goes. All other works are attributed to van der Goes based on stylistic comparison with the altarpiece.[9]

After Hugo's death the triptych was wrongly attributed to others, including Andrea del Castagno and Domenico Veneziano.[5] These two artists had produced the frescoes around the altarpiece, but were not involved in its design. In 1824, Karl Friedrich Schinkel identified it as the work of Hugo van der Goes. It was not until later that this theory became generally accepted.[5]

_-_WGA9706.jpg)

The central panel depicts the central Christian myths concerning the birth of the Christian saviour god: the nativity of Jesus, the adoration of the shepherds and the annunciation to the shepherds (in the far right background). Many interpretations of the iconography of the altarpiece have been proposed. The composition emphasizes the devotion to the Eucharist and the passion of Christ. The Eucharist is represented through the angels wearing liturgical vestments and the visual analogy of the sheaf of wheat with the body of Christ. The Passion is represented in the somber expressions of the figures and in the prominently placed flower still life in the front, which includes flowers such as a scarlet lily, white and purple irises and carnations. One of the containers in which the flowers are placed is of the albarello type. Albarelli were used as medicinal jars designed to hold apothecaries' ointments and dry drugs and thus reference in the picture the hospital setting (i.e. the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova) in which the altarpiece was to be hung. Some of the flowers in the flower still life were in the Renaissance also used for medicinal purposes and thus also reference the hospital setting. These references to medicinal powers also allude to the miraculous birth of Jesus, which, according to Christian literature, happened without the usual birth pains. The birth of Jesus itself is also supposed to have healing powers by delivering mankind from the so-called original sin, the Christian doctrine of humanity's state of sin, which resulted from the fall of man.[10]

The side panels depict the male (left wing) and female (right wing) members of the Portinari donor family who commissioned and donated the altarpiece. The right wing also includes a scene of the annunciation to the Magi and the left wing a scene of the journey of Mary and Joseph to Bethlehem.

Portraits

Hugo van der Goes is regarded as one of the major portraitists of 15th-century Europe. At that time portraiture was gaining importance in art because of the new individualism fostered by the rise of humanism.[11]

No known independent portraits by Hugo have survived. His achievements in this genre are only known by the donor portraits included in his devotional diptychs and triptychs. Examples are the left wing of the Saint Hippolytus Altarpiece, the central and right panels of which are by Dieric Bouts (c. 1475, Groeningemuseum, Bruges), the Portinari Alarpiece, the Trinity Altarpiece (between 1473 and 1478, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh) and the fragments of altarpieces such as the Portrait of a Man at Prayer with St John the Baptist (Walters Art Museum) and the Portrait of a Man.[8][11]

A common type of portrait in these devotional works was the depiction of a man or woman in prayer, experiencing a vision, often of the Virgin.[11]

The Portrait of a Man (c. 1575, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) is a good example of his portrait work. This small panel was cut down from a rectangular support to its current oval shape. It originally formed the right wing of a small altarpiece made up of only two paintings, known as a diptych. A likeness of the man’s wife may also have been placed at the right of the object of his veneration, balancing his image and forming a conventional triptych. The subject of the wing at the right of the male sitter would likely have been the Virgin and Child. Van der Goes succeeds in giving the sitter in the Portrait of a Man a bold presence and a decisive strength of character. He achieved these effects by placing the sitter on a higher level than the viewer and by setting off the illuminated head against the dark stone wall. He used chiaroscuro effects to further accentuate the modeling of the facial features so that they appear to be chiseled out of stone. It is perhaps these characteristics, as well as the appearance of the hands and background after they were overpainted by later restorers, that initially caused scholars to ascribe this portrait to Antonello da Messina. The stark realism of Hugo van der Goes' approach, with its meticulous rendering of the swarthy tones of the man's face, his emerging beard and his roughened hands joined in prayer, enhances the sense of fervent devotional piety conveyed by the sitter.

Similar treatments appear in the donor portrait of Hippolyte de Bertohoz on the left wing of the Saint Hippolytus Altarpiece and the head of Edward Bonkil on the exterior right wing of the Trinity Altarpiece.[8] The Portrait of a Man at Prayer with Saint John the Baptist (Walters Art Museum) shows similar traits. As at the time the display of strong emotion in public was frowned upon, Hugo resorted in this work to the most subtle facial expressions to express his sitters' mental state. In the Portrait of a Man at Prayer with Saint John the Baptist the man's deep concentration is wonderfully captured in his raised eyebrow and contracted muscles around the mouth.[11]

Stylistic development

Van der Goes is regarded as one of the most original and innovative early Netherlandish artists. As many works of van der Goes have not survived and most of the surviving works cannot be dated accurately, it is difficult to establish a stylistic development for van der Goes. The Portinari Altarpiece is the sole of his works that can be confidently linked to the artist.

Even so, art historians see a global development starting with a style close to the illusionism of van Eyck. This early style was characterised by a detailed description in rich colour and a single vanishing-point perspective as can be observed in the Monforte Altarpiece and Portinari central panel. Van der Goes may have learnt this style from Petrus Christus or Dieric Bouts.

Later works gradually abandoned illusionism for an increased emphasis on the artificiality of the picture as created image, divorced from reality. This effect was achieved by the use of a limited range of colours and the expressive distortion of figures as well as space.[2] Example of works in this later style are the Death of the Virgin (Groeningemuseum, Bruges) and the Adoration of the Shepherds (c. 1480, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin). Other characteristics imputed to these later works are a breakdown of space, a renunciation of still-life elements not directly related to the subject matter and an exaggerated agitation and an excess of expression in the figures. Early scholars saw the evolution as a reflection of the increasing mental instability of the artist. Later interpretations gave much weight to the artist's adherence to the Modern Devotion movement as an important influence. These interpretations see the later paintings as attempts by van der Goes to translate the ideas of this movement into a visual medium. In particular the movement's emphasis on meditation is seen as playing a key role in the artist abandoning illusionism.[12]

The muted coloring of the late Adoration of the Shepherds seemed to support the interpretation of a stylistic evolution away from illusionism. A recent restoration of the Adoration has provided new visual evidence, which contradicts the earlier reading as it revealed that rather than muted the painting was bright and strongly illusionistic.[13]

Not all scholars agree on a stylistic development in van der Goes' work. Some insist that his career of only 15 years was too short to allow for a development to be distinguished. Other scholars regard van der Goes as an artist with an ability to create in the same period very different types and styles of work and even within a single composition. They maintain that van der Goes had the flexibility and range to use or discard techniques where they suited his purpose.[2]

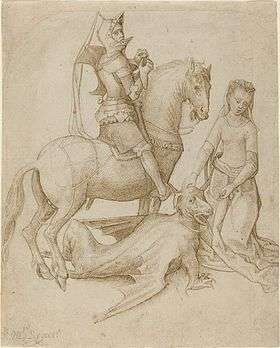

Drawings

Hugo van der Goes left a large number of drawings. These drawings or the paintings themselves were used by followers to produce large numbers of copies of compositions from his own hand that are now lost.[9] After van der Goes' death in 1482, the Ghent book illustrator Alexander Bening, who was married to a niece of the painter, likely inherited the model drawings and patterns of van der Goes. This would explain the presence of his compositions in the illustrated book of hours created by the Ghent-Bruges school of illuminators. Simon Bening, the son of Alexander Bening, must have introduced the model drawings by van der Goes in Bruges.[1]

A drawing of Jacob and Rachel preserved at the Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford is thought to be a rare surviving autograph drawing. It may have been a preliminary study for a stained glass window.[14]

Works

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Till-Holger Borchert, Hugo van der Goes at Flemish Primitives

- 1 2 3 4 Catherine Reynolds. "Goes, Hugo van der." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 19 May 2016

- ↑ J. Koldeweij, A. Hermesdorf, P. Huvenne, De schilderkunst der Lage Landen: De Middeleeuwen en de zestiende eeuw, Amsterdam University Press, 2006, p. 106-110 (Dutch)

- 1 2 3 4 Wolfgang Stechow, Northern Renaissance Art, 1400-1600: Sources and Documents, Northwestern University Press, 1966, p. 15-18

- 1 2 3 Koster, Margaret (1999). Hugo van der Goes's "Portinari Altarpiece": Northern invention and Florentine reception. Columbia University.

- ↑ Colin Thompson, Lorne Campbell, Hugo van der Goes and the Trinity panels in Edinburgh, Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland; London : distributed by A. Zwemmer, 1974, p. 5

- ↑ Susan Koslow, "The Impact of Hugo van der Goes’s Mental Illness and Late-Medieval Religious Attitudes on the Death of the Virgin," in Healing and History, Essays for George Rosen, ed. Charles E. Rosenberg (New York: Neale Watson Academic Publications, 1979), p. 27-50

- 1 2 3 Portrait of a Man at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- 1 2 3 Lorne Campbell, The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings National Gallery Company, p. 240

- ↑ Julia I. Miller, Miraculous Childbirth and the Portinari Altarpiece, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 77, No. 2 (June 1995), College Art Association, pp. 249-261

- 1 2 3 4 Portrait of a Man at Prayer with Saint John the Baptist at the Walters Art Museum

- ↑ Bernhard Ridderbos, Hugo van der Goes's "Death of the Virgin" and the Modern Devotion: an analysis of a creative process, in: Oud Holland Vol. 120, No. 1/2 (2007), pp. 1-30, Published by: Brill

- ↑ Jessica Buskirk, “Hugo van der Goes’s Adoration of the Shepherds: Between Ascetic Idealism and Urban Networks in Late Medieval Flanders,” JHNA 6:1 (Winter 2014), DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2014.6.1.1

- ↑ Werner Schade, "The Meeting of Jacob and Rachel" by Hugo van der Goes: A Reappraisal, in: Master Drawings Vol. 29, No. 2 (Summer, 1991), pp. 187-193

External links

Media related to Hugo van der Goes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hugo van der Goes at Wikimedia Commons

External media

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) | |

|

|