Illyrians

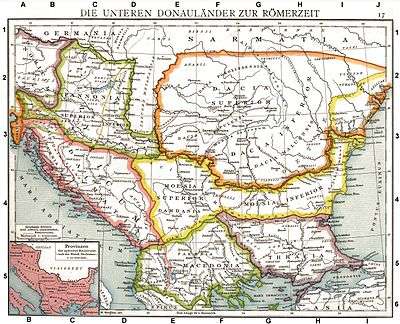

The Illyrians (Ancient Greek: Ἰλλυριοί, Illyrioi; Latin: Illyrii or Illyri) were a group of Indo-European tribes in antiquity, who inhabited part of the western Balkans and the south-eastern coasts of the Italian peninsula (Messapia). [1] The territory the Illyrians inhabited came to be known as Illyria to Greek and Roman authors, who identified a territory that corresponds to the Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Slovenia, Montenegro, part of Serbia and most of Albania, between the Adriatic Sea in the west, the Drava river in the north, the Morava river in the east and the mouth of the Aoos river in the south.[2] The first account of Illyrian peoples comes from the Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax, an ancient Greek text of the middle of the 4th century BC that describes coastal passages in the Mediterranean.[3]

These tribes, or at least a number of tribes considered "Illyrians proper", of which only small fragments are attested enough to classify as branches of Indo-European;[4] were probably extinct by the 2nd century AD.[5]

The name "Illyrians", as applied by the ancient Greeks to their northern neighbors, may have referred to a broad, ill-defined group of peoples, and it is today unclear to what extent they were linguistically and culturally homogeneous. In fact, an Illyric origin was and still is attributed also to a few ancient peoples in Italy, in particular the Iapyges, Dauni and Messapi, as it is thought that, most likely, they had followed Adriatic shorelines to the peninsula, coming from the geographic "Illyria". The Illyrian tribes never collectively regarded themselves as 'Illyrians', and it is unlikely that they used any collective nomenclature for themselves.[6] In fact, the name Illyrians seems to be the name applied to a specific Illyrian tribe, which was the first to come in contact with the ancient Greeks during the Bronze Age,[7] causing the name Illyrians to be applied to all people of similar language and customs.[8]

The term "Illyrians" last appears in the historical record in the 7th century, referring to a Byzantine garrison operating within the former Roman province of Illyricum.[9] Contemporary historians conclude that modern Albanian language might have descended from a southern Illyrian dialect.[10][11]

Illyrians in Greek mythology

_(English).jpg)

In later Greek mythology,[12] Illyrius was the son of Cadmus and Harmonia who eventually ruled Illyria and became the eponymous ancestor of the whole Illyrian people.[13]

Illyrius had multiple sons (Encheleus, Autarieus, Dardanus, Maedus, Taulas and Perrhaebus) and daughters (Partho, Daortho, Dassaro and others). From these, sprang the Taulantii, Parthini, Dardani, Encheleae, Autariates, Dassaretae and the Daors. Autareius had a son Pannonius or Paeon and these had sons Scordiscus and Triballus.[8] A later version of this mythic genealogy gives as parents Polyphemus and Galatea, who gave birth to Celtus, Galas, and Illyrius,[14] three brothers, progenitors respectively of Celts, Galatians and Illyrians expresses perceived similarities to Celts and Gauls on the part of the mythographe.

Origins

.jpg)

Even before the advent of post-modernism, scholars recognized a "difficulty in producing a single theory on the ethnogenesis of the Illyrians" given their heterogeneous nature.[15] Nevertheless, scholars traditionally looked for the "origins" of the Illyrian peoples centuries, even millennia, before their first historical attestation. Following the theories of Gustaf Kossinna, scholars sought to equate tribes mentioned by later Greco-Roman historians with preceding Bronze and Iron Age archaeological cultures. In particular, scholars such as Julian Pokorny and Richard Pittioni placed the Illyrian 'homeland' within the Luzatian culture (in contemporary eastern Germany and western Poland), itself an offshoot of the trans-Central European Urnfield culture. From c. 1200 BC, the 'proto-Illyrian' bearers of the Lausitz culture are said to have engaged in widespread migrations throughout Europe and even Asia Minor.[16] With regard to the Balkans, their movement south in turn initiated the Dorian migrations into southern Greece, which allegedly caused the downfall of the Mycenaean civilization.[17] These Pan-Illyrian theories have since been dismissed by scholars, based as they were on racialistic notions of Nordicism and Aryanism.[18]

The above theories have found little archaeological corroboration, as no convincing evidence for significant migratory movements from the Luzatian culture into the west Balkans have ever been found.[19][20] Rather, archaeologists from the former Yugoslavia highlighted the continuity between the Bronze and succeeding Iron Age (especially in regions such as Donja Dolina, central Bosnia-Glasinac, and northern Albania (Mat river basin)), ultimately developing the so-called "autochthonous theory" of Illyrian genesis.[20] The "autochthonous" model was most elaborated upon by Alojz Benac and B. Čović. They argued (following the "Kurgan hypothesis") that the 'proto-Illyrians' had arrived much earlier, during the Bronze Age as nomadic Indo-Europeans from the steppe. From that point, there was a gradual Illyrianization of the western Balkans leading to historic Illyrians, with no early Iron Age migration from northern Europe. He did not deny a minor cultural impact from the northern Urnfield cultures, however "these movements had neither a profound influence on the stability.. of the Balkans, nor did they affect the ethnogenesis of the Illyrian ethnos".[21]

Aleksandar Stipčević raised concerns regarding Benac's all-encompassing scenario of autochthonous ethnogenesis. He points out "can one negate the participation of the bearers of the field-urn culture in the ethnogenesis of the Illyrian tribes who lived in present-day Slovenia and Croatia" or "Hellenistic and Mediterranean influences on southern Illyrians and Liburnians?".[21] He concludes that Benac's model is only applicable to the Illyrian groups in Bosnia, western Serbia and a part of Dalmatia, where there had indeed been a settlement continuity and 'native' progression of pottery sequences since the Bronze Age. Following prevailing trends in discourse on identity in Iron Age Europe, current anthropological perspectives reject older theories of a longue duree (long term) ethnogenesis of Illyrians,[22] even where 'archaeological continuity' can be demonstrated to Bronze Age times.[23] They rather see the emergence of historic Illyrians tribes as a more recent phenomenon - just prior to their first attestation.[22] Prior to the 5th century BCE, communities in "Illyria" were small, kin-based, non-heriarchical societies; albeit ones which entertained complex social networks and possessed central fortified places (gradinas), akin to western oppida. The exception to this are the communities in Glasinac and Mati, which already showed evidence of long-distance exchange and social stratification by the 7th century BCE.

The impetus behind the emergence of larger regional groups, such as "Iapodes", "Liburnians", "Pannonians" etc., is traced to increased contacts with the Mediterranean and La Tène 'global worlds'.[25] This catalyzed "the development of more complex political institutions and the increase in differences between individual communities".[26] Emerging local elites selectively adopted either La Tène or Hellenistic and, later, Roman cultural templates "in order to legitimise and strengthen domination within their communities. They were competing fiercely through either alliance or conflict and resistance to Roman expansion. Thus, they established more complex political alliances, which convinced (Greco-Roman) sources to see them as ‘ethnic’ identities."[27] Contemporary perspectives again highlight that the term "Illyrian" was a 'catch-all' exonym used by the Greeks and Romans to denote diverse communities beyond Epirus and Macedonia. Each was differentially conditioned by specific local cultural, ecological and economic factors; none of which fall into a compact, unitary "Illyrian" narrative.

Nomenclature

.jpg)

The name of Illyrians as applied by the ancient Greeks to their northern neighbours may have referred to a broad, ill-defined group of peoples, and it is today unclear to what extent they were linguistically and culturally homogeneous. The Illyrian tribes never collectively regarded themselves as 'Illyrians', and it is unlikely that they utilized any collective nomenclature for themselves.[6]

The term Illyrioi may originally have designated only a single people who came to be widely known to the Greeks due to proximity.[28] This occurred during the Bronze Age, when Greek tribes were neighboring the southernmost Illyrian tribe of that time in the Zeta plain of Montenegro.[7] Indeed, such a people known as the Illyrioi have occupied a small and well-defined part of the south Adriatic coast, around Skadar Lake astride the modern frontier between Albania and Montenegro. The name may then have expanded and come to be applied to ethnically different peoples such as the Liburni, Delmatae, Iapodes, or the Pannonii. In any case, most modern scholars are certain the Illyrians constituted a heterogeneous entity.[29]

Pliny the Elder referred, in his Natural History, to "Illyrians proper" (Illyrii proprie dicti) as natives in the south of Roman Dalmatia. Appian's Illyrian Wars employed the more common broader usage, simply stating that Illyrians lived beyond Macedonia and Thrace, from Chaonia and Thesprotia to the Danube River.[30]

Depiction in Greco-Roman historiography

Illyrians were regarded as bloodthirsty, unpredictable, turbulent, and warlike by Greeks and Romans.[31] They were seen as savages on the edge of their world.[32] Polybius (3rd century BC) wrote: "the Romans had freed the Greeks from the enemies of all mankind".[33] According to the Romans, the Illyrians were tall and well-built.[34] Herodianus writes that "Pannonians are tall and strong always ready for a fight and to face danger but slow witted".[35] Livy wrote "...the coasts of Italy destitute of harbours, and, on the right, the Illyrians, Liburnians, and Istrians, nations of savages, and noted in general for piracy, he passed on to the coasts of the Venetians". Illyrian rulers wore bronze torques around their necks.[36]

History

Hellenistic period

Illyria appears in Greco-Roman historiography from the 4th century BC. The Illyrians formed several kingdoms in the central Balkans, and the first known Illyrian king was Bardyllis. Illyrian kingdoms were often at war with ancient Macedonia, and the Illyrian pirates were also a significant danger to neighbouring peoples. At the Neretva Delta, there was a strong Hellenistic influence on the Illyrian tribe of Daors. Their capital was Daorson located in Ošanići near Stolac in Herzegovina, which became the main center of classical Illyrian culture. Daorson, during the 4th century BC, was surrounded by megalithic, 5 meter high stonewalls, composed out of large trapeze stones blocks. Daors also made unique bronze coins and sculptures. The Illyrians even conquered Greek colonies on the Dalmatian islands. Queen Teuta was famous for having waged wars against the Romans.

After Philip II of Macedon defeated Bardylis (358 BC), the Grabaei under Grabos became the strongest state in Illyria.[37] Philip II killed 7,000 Illyrians in a great victory and annexed the territory up to Lake Ohrid.[38] Next, Philip II reduced the Grabaei, and then went for the Ardiaei, defeated the Triballi (339 BC), and fought with Pleurias (337 BC).[39]

In the Illyrian Wars of 229 BC, 219 BC and 168 BC Rome overran the Illyrian settlements and suppressed the piracy that had made the Adriatic unsafe for Italian commerce.[40] There were three campaigns, the first against Teuta the second against Demetrius of Pharos[41] and the third against Gentius. The initial campaign in 229 BC marks the first time that the Roman Navy crossed the Adriatic Sea to launch an invasion.[42]

The Roman Republic subdued the Illyrians during the 2nd century BC. An Illyrian revolt was crushed under Augustus, resulting in the division of Illyria in the provinces of Pannonia in the north and Dalmatia in the south.

Roman rule

The Roman province of Illyricum or Illyris Romana or Illyris Barbara or Illyria Barbara replaced most of the region of Illyria.[43] It stretched from the Drilon river in modern Albania to Istria (Croatia) in the west and to the Sava river (between Bosnia and Herzegovina and northern Croatia) in the north.[43] Salona (Solin near modern Split in Croatia) functioned as its capital. The regions which it included changed through the centuries though a great part of ancient Illyria remained part of Illyricum as a province while south Illyria became Epirus Nova.

After 9 AD, the remnants of Illyrian tribes moved to new coastal cities and larger and more capable civitates.[44]

The prefecture of Illyricum was established in the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire), existing between 376 and the 7th century. The northern half of formerly Illyrian-inhabited territory was overrun by the Slavic incursions in the 6th and 7th centuries and was ultimately absorbed into the medieval states of Serbia and Croatia.

Warfare

The history of Illyrian warfare spanned from around the 10th century BC up to the 1st century AD in the region defined by Ancient Greek and Latin historians as Illyria. It concerns the armed conflicts of the Illyrian tribes and their kingdoms in the Balkans in Italy as well as pirate activity in the Mediterranean and Adriatic seas. Apart from conflicts between Illyrians and neighbouring nations and tribes, numerous wars were recorded among Illyrian tribes also.

Religion

The mythology and religion of the Illyrians is only known through mention of Illyrian deities on Roman Empire period monuments, some with interpretatio Romana.[45] There appears to be no single most prominent Illyrian god and there would have been much variation between individual Illyrian tribes. According to John Wilkes, the Illyrians did not develop a uniform cosmology on which to center their religious practices.[46] The Illyrian town of Rhizon (present-day Risan, Montenegro) had its own protector called Medauras depicted as carrying a lance and riding on horseback.[47]

Human sacrifice also played a role in the lives of the Illyrians.[48] Arrian records the chieftain Cleitus the Illyrian as sacrificing three boys, three girls and three rams just before his battle with Alexander the Great. The most common type of burial among the Iron Age Illyrians was tumulus or mound burial. The kin of the first tumuli was buried around that, and the higher the status of those in these burials the higher the mound. Archaeology has found many artifacts placed within these tumuli such as weapons, ornaments, garments and clay vessels. Illyrians believed these items were necessary for a dead person's journey into the afterlife.

Extinction of ethnicity and language

The Illyrians were subject to varying degrees of Celticization,[49] Hellenization,[50] Romanization,[51] and later Slavicization.

The languages of Illyria were Indo-European. It is not clear whether the Illyrian languages belonged to the centum or the satem group. The vast majority of our knowledge of Illyrian is based on Messapian, if the latter is considered an Illyrian dialect. The non-Messapic testimonies of Illyrian are too fragmentary to allow any conclusions whether Messapian should be considered part of Illyrian proper. It has been widely thought that Messapian was related to Illyrian. Messapian (also known as Messapic) is an extinct Indo-European language of south-eastern Italy, once spoken in Messapia (modern Salento). It was spoken by the three Iapygian tribes of the region: the Messapians, the Daunii and the Peucetii. The Illyrian languages were once thought to be connected to the Venetic language but this view was abandoned.[52] Other scholars have linked them with the adjacent Thracian language supposing an intermediate convergence area or dialect continuum, but this view is also not generally supported. All these languages were likely extinct by the 5th century[53] although traditionally, the Albanian language is identified as the descendant of Illyrian dialects that survived in remote areas of the Balkans during the Middle Ages, but evidence "is too meager and contradictory for us to know whether the term Illyrian even referred to a single language".[54] The ancestor dialects of Albanian would have survived somewhere along the boundary of Latin and Greek linguistic influence (the Jireček Line). An alternative hypothesis favoured by some linguists is that Albanian is descended from Thracian.[53] Not enough is known of the ancient language to completely prove or disprove either hypothesis (see Origin of Albanians).[55]

Archaeology

There are few remains to connect with the Bronze Age with the later Illyrians in the western Balkans. Moreover, with the notable exception of Pod near Bugojno in the upper valley of the Vrbas River, nothing is known of their settlements. Some hill settlements have been identified in western Serbia, but the main evidence comes from cemeteries, consisting usually of a small number of burial mounds (tumuli). In the cemeteries of Belotić and Bela Crkva, the rites of exhumation and cremation are attested, with skeletons in stone cists and cremations in urns. Metal implements appear here side-by-side with stone implements. Most of the remains belong to the fully developed Middle Bronze Age.

During the 7th century BC, the beginning of the Iron Age, the Illyrians emerge as an ethnic group with a distinct culture and art form. Various Illyrian tribes appeared, under the influence of the Halstatt cultures from the north, and they organized their regional centers.[56] The cult of the dead played an important role in the lives of the Illyrians, which is seen in their carefully made burials and burial ceremonies, as well as the richness of the burial sites. In the northern parts of the Balkans, there existed a long tradition of cremation and burial in shallow graves, while in the southern parts, the dead were buried in large stone, or earth tumuli (natively called gromile) that in Herzegovina were reaching monumental sizes, more than 50 meters wide and 5 meters high. The Japodian tribe (found from Istria in Croatia to Bihać in Bosnia) have had an affinity for decoration with heavy, oversized necklaces out of yellow, blue or white glass paste, and large bronze fibulas, as well as spiral bracelets, diadems and helmets out of bronze. Small sculptures out of jade in form of archaic Ionian plastic are also characteristically Japodian. Numerous monumental sculptures are preserved, as well as walls of citadel Nezakcij near Pula, one of numerous Istrian cities from Iron Age. Illyrian chiefs wore bronze torques around their necks much like the Celts did.[57] The Illyrians were influenced by the Celts in many cultural and material aspects and some of them were Celticized, especially the tribes in Dalmatia[58] and the Pannonians.[59] In Slovenia, the Vače situla was discovered in 1882 and attributed to Illyrians. Prehistoric remains indicate no more than average height, male 165 cm (5 ft 5 in), female 153 cm (5 ft 0 in).[35]

Legacy

Middle Ages

The Illyrians were mentioned for the last time in the Miracula Sancti Demetrii during the 7th century.[60] With the disintegration of the Roman Empire, Gothic and Hunnic tribes raided the Balkan peninsula, forcing many Illyrians to seek refuge in the highlands. With the arrival of the Slavs in the 6th century, most Illyrians were Slavicized.

Early modern usage

During the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the term "Illyrian" was used to describe Slavs living within the territories of Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Italy, Austria, Hungary and Serbia (and in other countries abroad). The term was revived again during the Habsburg Monarchy, but it was designated towards South Slavs.

In nationalism

When Napoleon conquered part of the South Slavic lands in the beginning of the 19th century, these areas were named after ancient Illyrian provinces. Under the influence of Romantic nationalism, a self-identified "Illyrian movement" in the form of a Croatian national revival, opened a literary and journalistic campaign initiated by a group of young Croatian intellectuals during the years of 1835–49.[61] This movement, under the banner of Illlyrism, aimed to create a Croatian national establishment under Austro-Hungarian rule but was repressed by the Habsburg authorities after the failed Revolutions of 1848.

The possible continuity between the Illyrian populations of the Western Balkans in antiquity and the Albanians has played a significant role in Albanian nationalism from the 19th century until the present day. For example, Ibrahim Rugova, the first President of Kosovo introduced the "Flag of Dardania" on October 29, 2000, Dardania being the name for a Thraco-Illyrian region roughly coterminous with modern Kosovo.

See also

- List of ancient tribes in Illyria

- List of rulers in Illyria

- Illyrian weaponry

- Illyrian languages

- Illyrian warfare

- Paleo-Balkan mythology

- Adriatic Veneti

- Liburnians

- Prehistory of the Balkans

- Early history of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- History of Croatia before the Croats

- Prehistoric Serbia

- Origin of Albanians

References

- ↑ Frazee 1997, p. 89: "The Balkan peninsula had three groups of Indo-Europeans prior to 2000 BC. Those on the west were the Illyrians; those on the east were the Thracians; and advancing down the southern part of the Balkans, the Greeks."

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, pp. 6, 92; Boardman & Hammond 1982, p. 261

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 94.

- ↑ Eastern Michigan University Linguist List: The Illyrian Language: "An ancient language of the Balkans. Based upon geographical proximity, this is traditionally seen as the ancestor of Modern Albanian. It is more likely, however, that Thracian is Modern Albanian's ancestor, since both Albanian and Thracian belong to the satem group of Indo-European, while Illyrian belonged to the centum group. 2nd half of 1st Millennium BC - 1st half of 1st Millennium AD."

- ↑ Fol 2002, p. 225: "Romanisation was total and complete by the end of the 4th century A.D. In the case of the Illyrian elements a Romance intermediary is inevitable as long as Illyrian was probably extinct in the 2nd century A.D."

- 1 2 Roisman & Worthington 2010, p. 280: "The Illyrians certainly never collectively called themselves Illyrians, and it is unlikely that they had any collective name for themselves."

- 1 2 Boardman 1982, p. 629.

- 1 2 Wilkes 1995, p. 92.

- ↑ Schaefer 2008, p. 130.

- ↑ Ceka 2005, pp. 40–42, 59

- ↑ "Albania". London: Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 September 2005.

- ↑ E.g. in the myth compendium Bibliotheca of PseudoApollodorus III.5.4, which is not earlier than the first century BC.

- ↑ Grimal & Maxwell-Hyslop 1996, p. 230; Apollodorus & Hard 1999, p. 103 (Book III, 5.4)

- ↑ Grimal & Maxwell-Hyslop 1996, p. 168.

- ↑ Stipčević 1977, p. 15.

- ↑ Stipcevic, 1977, p 16

- ↑ Stipčević 1977, p. 16.

- ↑ Wilkes 1992, p. 38.

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 81.

- 1 2 Stipčević 1977, p. 17.

- 1 2 Stipčević 1977, p. 19.

- 1 2 Dzino 2012.

- ↑ Wilkes 1992, p. 39 argues that "cannot fail to impress through their weight of archaeological evidence; but material remains alone can never tell the whole story and can mislead."

- ↑ Maggiulli, Sull'origine dei Messapi, 1934; D’Andria, Messapi e Peuceti, 1988; I Messapi, Taranto 1991

- ↑ Dzino 2012, pp. 74-76.

- ↑ Dzino 2012, p. 97.

- ↑ Dzino 2012, pp. 84-85.

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, pp. 81, 183.

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 38: "Just as ancient writers could discover no satisfactory general explanation for the origin of Illyrians, so most modern scholars, even though now possessed of a mass of archaeological and linguistic evidence, can assert with confidence only that Illyrians were not a homogeneous entity, though even that is today challenged with vigour by historians and archaeologists working within the perspective of modern Albania."

- ↑ Roman History: "The Illyrian Wars", livius.org; accessed April 3, 2014

- ↑ Whitehorne 1994, p. 37; Eckstein 2008, p. 33; Strauss 2009, p. 21; Everitt 2006, p. 154.

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 4

- ↑ Champion 2004, p. 113.

- ↑ Juvenal 2009, p. 127.

- 1 2 Wilkes 1995, p. 219.

- ↑ Wilkes 1992, p. 223.

- ↑ Hammond 1994, p. 438.

- ↑ Hammond 1993, p. 106.

- ↑ Hammond 1993, p. 107.

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 158.

- ↑ Boak & Sinnigen 1977, p. 111.

- ↑ Gruen 1986, p. 76.

- 1 2 Smith 1874, p. 218.

- ↑ Wilkes 1969, p. 156.

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 245: "...Illyrian deities are named on monuments of the Roman era, some in equation with gods of the classical pantheon (see figure 34)."

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 244: "Unlike Celts, Dacians, Thracians or Scythians, there is no indication that Illyrians developed a uniform cosmology on which their religious practice was centred. An etymology of the Illyrian name linked with serpent would, if it is true, fit with the many representations of..."

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 247.

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 123.

- ↑ Bunson 1995, p. 202; Mócsy 1974.

- ↑ Pomeroy et al. 2008, p. 255

- ↑ Bowden 2003, p. 211; Kazhdan 1991, p. 248.

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 183.

- 1 2 Eastern Michigan University Linguist List: The Illyrian Language, linguistlist.org; accessed April 3, 2014

- ↑ Ammon et al. 2006, p. 1874: "Traditionally, Albanian is identified as the descendant of Illyrian, but Hamp (1994a) argues that the evidence is too meager and contradictory for us to know whether the term Illyrian even referred to a single language."

- ↑ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 9;Fortson 2004

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 140.

- ↑ Wilkes 1995, p. 233.

- ↑ Bunson 1995, p. 202; Hornblower & Spawforth 2003, p. 426

- ↑ Hornblower & Spawforth 2003, p. 1106

- ↑ Juka 1984, p. 60: "Since the Illyrians are referred to for the last time as an ethnic group in Miracula Sancti Demetri (7th century AD), some scholars maintain that after the arrival of the Slavs the Illyrians were extinct."

- ↑ Despalatovic 1975.

Sources

- Ammon, Ulrich; Dittmar, Norbert; Mattheier, Klaus J.; Trudgill, Peter (2006), Sociolinguistics: An International Handbook of the Science of Language and Society, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 3-11-018418-4

- Apollodorus; Hard, Robin (1999), The Library of Greek Mythology, Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-283924-1

- Benać, Alojz (1964). "Vorillyrier, Protoillyrier und Urillyrier". Symposium sur la Délimitation Territoriale et Chronologique des Illyriens à l’Epoque Préhistorique. Sarajevo: Naučno društvo SR Bosne i Hercegovine: 59–94.

- Boak, Arthur Edward Romilly; Sinnigen, William Gurnee (1977), A History of Rome to A.D. 565, Macmillan

- Boardman, John (1982), The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume III, Part I: The Prehistory of the Balkans; the Middle East and the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth Centuries B.C., Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-22496-9

- Boardman, John; Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1982), The Cambridge Ancient History: The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Six Centuries B.C, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-23447-6

- Bowden, William (2003), Epirus Vetus: The Archaeology of a Late Antique Province, Duckworth, ISBN 0-7156-3116-0

- Bunson, Matthew (1995), A Dictionary of the Roman Empire, Oxford University Press US, ISBN 0-19-510233-9

- Ceka, Neritan (2005), The Illyrians to the Albanians, Publ. House Migjeni, ISBN 99943-672-2-6

- Champion, Craige Brian (2004), Cultural Politics in Polybius's Histories, Berkeley, California: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-23764-1

- Despalatovic, Elinor Murray (1975), Ljudevit Gaj and the Illyrian Movement, New York: East European Quarterly

- Dzino, Danijel (2012), "Contesting Identities of pre-Roman Illyricum", Ancient West & East, 11: 69–95, doi:10.2143/AWE.11.0.2175878

- Eckstein, Arthur M. (2008), Rome Enters the Greek East: From Anarchy to Hierarchy in the Hellenistic Mediterranean, 230-170 BC, Blackwell Pub, ISBN 1-4051-6072-1

- Evans, Arthur John (1883–1885). "Antiquarian Researches in Illyricum, I-IV (Communicated to the Society of Antiquaries of London)". Archaeologia. Westminster: Nichols & Sons.

- Evans, Arthur John (1878), Illyrian Letters, Longmans, Green, and Co, ISBN 1-4021-5070-9

- Everitt, Anthony (2006), Augustus: The Life of Rome's First Emperor, Random House, Incorporated, ISBN 1-4000-6128-8

- Fortson, Benjamin W. (2004), Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 1-4051-0316-7

- Frazee, Charles A. (1997), World History: Ancient and Medieval Times to A.D. 1500, Barron's Educational Series, ISBN 0-8120-9765-3

- Grimal, Pierre; Maxwell-Hyslop, A. R. (1996), The Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 0-631-20102-5

- Gruen, Erich S. (1986), The Hellenistic World and the Coming of Rome, Volume 1, Berkeley, California: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-05737-6

- Hammond, N. G. L (1993). Studies concerning Epirus and Macedonia before Alexander. Hakkert.

- Hammond, N. G. L. (1994). "Illyrians and North-west Greeks". The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 6: The Fourth Century BC. Cambridge University Press.

- Harding, Phillip (1985), From the End of the Peloponnesian War to the Battle of Ipsus, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29949-7

- Hornblower, Simón; Spawforth, Antony (2003), The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-860641-9

- Juka, S. S. (1984), Kosova: The Albanians in Yugoslavia in Light of Historical Documents: An Essay, Waldon Press

- Juvenal, Decimus Junius (2009), The Satires of Decimus Junius Juvenalis, and of Aulus Persius Flaccus, BiblioBazaar, LLC, ISBN 1-113-52581-9

- Kazhdan, Aleksandr Petrovich (1991), The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-504652-8

- Kohl, Philip L.; Fawcett, Clare P. (1995), Nationalism, Politics and the Practice of Archaeology, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-48065-5

- Kühn, Herbert (1976), Geschichte der Vorgeschichtsforschung, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 3-11-005918-5

- Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 1-884964-98-2

- Mazaris, Maximus (1975), Mazaris' Journey to Hades or Interviews with Dead Men about Certain Officials of the Imperial Court (Seminar Classics 609), Buffalo, New York: Department of Classics, State University of New York at Buffalo

- Mócsy, András (1974), Pannonia and Upper Moesia: A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire, Routledge, ISBN 0-7100-7714-9

- Pomeroy, Sarah B.; Burstein, Stanley M.; Donlan, Walter; Roberts, Jennifer Tolbert (2008), A Brief History of Ancient Greece: Politics, Society, and Culture, Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-537235-2

- Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (2010), A Companion to Ancient Macedonia, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 1-4051-7936-8

- Schaefer, Richard T. (2008), Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society, SAGE Publications, ISBN 1-4129-2694-7

- Smith, William (1874), A Smaller Classical Dictionary of Biography, Mythology, and Geography: Abridged from the Larger Dictionary, J. Murray

- Srejovic, Dragoslav (1996), Illiri e Traci, Editoriale Jaca Book, ISBN 88-16-43607-7

- Stipčević, Aleksandar (1977), The Illyrians: History and Culture, Noyes Press, ISBN 978-0-8155-5052-5

- Stipčević, Alexander (1989). Iliri: povijest, život, kultura. Zagreb: Školska knjiga.

- Strauss, Barry (2009), The Spartacus War, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 1-4165-3205-6

- Whitehorne, John Edwin George (1994), Cleopatras, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-05806-6

- Wilkes, J. J. (1969). Dalmatia. Harvard University Press.

- Wilkes, J. J. (1992). The Illyrians. Blackwell. ISBN 06-3119-807-5.

- Wilkes, J. J. (1995), The Illyrians, Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 0-631-19807-5

External links

Media related to Illyria and Illyrians at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Illyria and Illyrians at Wikimedia Commons- Phallic Cult of the Illyrians