Prehistory of Southeastern Europe

- For the history of Earth before the occupation by the genus homo, including the period of early hominins, see Geology of Europe and Human evolution.

The prehistory of Southeastern Europe, defined roughly as the territory of the wider Balkan peninsula (including the territories of the modern countries of Albania, Kosovo, Croatia, Serbia, Macedonia, Greece, Bosnia, Romania, Bulgaria, Moldova and Turkey) covers the period from the Upper Paleolithic, beginning with the presence of Homo sapiens in the area some 44,000 years ago, until the appearance of the first written records in Classical Antiquity, in Greece as early as the 8th century BC.

Human prehistory in Southeastern Europe is conventionally divided into smaller periods, such as Upper Paleolithic, Holocene Mesolithic/Epipaleolithic, Neolithic Revolution, expansion of Proto-Indo-Europeans, and Protohistory. The changes between these are gradual. For example, depending on interpretation, protohistory might or might not include Bronze Age Greece (2800–1200 BC),[1] Minoan, Mycenaean, Thracian and Venetic cultures. By one interpretation of the historiography criterion, Southeastern Europe enters protohistory only with Homer (See also Historicity of the Iliad, and Geography of the Odyssey). At any rate, the period ends before Herodotus in the 5th century BC.[2]

Paleolithic

- (2,600,000 – 13,000 BP)

Balkan Transition to the Upper Paleolithic

- (2,600,000 – 50,000 BP)

The earliest evidence of human occupation discovered in the Balkans, in Kozarnika Bulgaria, date from at least 1.4 million years ago.[3]

There is evidence of human presence in the Balkans from the Lower Paleolithic onwards, but the number of sites is limited. According to Douglass W. Bailey:[4]

| “ | it is important to recognize that the Balkan Upper Palaeolithic was a long period containing little significant internal change. Thus, the Balkans transition was not as dramatic as in other European regions. Crucial changes that define the earliest emergence of Homo sapiens sapiens are presented at Bacho Kiro at 44,000 BC. The Bulgarian key Palaeolithic caves named Bacho Kiro and Temnata Dupka with early Upper Palaeolithic material correlate that the transition was gradual. | ” |

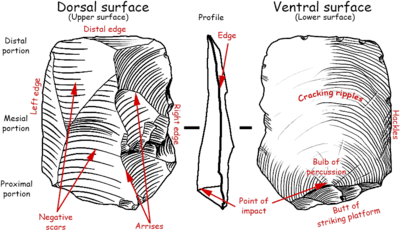

The Palaeolithic period, literally the “Old Stone Age”, is an ancient cultural level of human development characterized by the use of unpolished chipped stone tools. The transition from Middle to Upper Palaeolithic is directly related to the development of behavioural modernity by hominids around 40,000 years BP. To denote the great significance and degree of change, this dramatic shift from Middle to Upper Palaeolithic is sometimes called the Upper Palaeolithic Revolution.

In the late Pleistocene, various components of the transition–material culture and environmental features (climate, flora, and fauna) indicate continual change, differing from contemporary points in other parts of Europe. The aforementioned aspects leave some doubt that the term Upper Palaeolithic Revolution is appropriate to the Balkans.

In general, continual evolutionary changes are the first crucial characteristic of the transition to the Upper Palaeolithic in the Balkans. The notion of the Upper Palaeolithic Revolution that has been developed for core European regions is not applicable to the Balkans. What is the reason? This particularly significant moment and its origins are defined and enlightened by other characteristics of the transition to upper Old Stone Age. The environment, climate, flora and fauna corroborate the implications.

During the last interglacial period and the most recent glaciation of the Pleistocene (from 131,000 till 12,000 BP), Europe was very different from the Balkans. The glaciations did not affect southeastern Europe to the extent that they did in the northern and central regions. The evidence of forest and steppe indicate the influence was not so drastic; some species of flora and fauna survived only in the Balkans. The Balkans today still abound in species endemic only to this part of Europe.

The notion of gradual transition (or evolution) best defines Balkan Europe from about 50,000 BP. In this sense, the material culture and natural environment of the Balkans of the late Pleistocene and the early Holocene were distinct from other parts of Europe. Douglass W. Bailey writes in Balkan Prehistory: Exclusion, Incorporation and Identity: “Less dramatic changes to climate, flora and fauna resulted in less dramatic adaptive, or reactive, developments in material culture.”

Thus, in speaking about southeastern Europe, many classic conceptions and systematizations of human development during the Palaeolithic (and then by implication the Mesolithic) should not be considered correct in all cases. In this regard, the absence of Upper Palaeolithic cave art in the Balkans does not seem to be surprising. Civilisations develop new and distinctive characteristics as they respond to new challenges in their environment.

Upper Palaeolithic

- (50,000 – 20,000 BP)

In 2002, some of the oldest modern human (Homo sapiens sapiens) remains in Europe were discovered in the "Cave With Bones" (Peștera cu Oase), near Anina, Romania.[5] Nicknamed "John of Anina" (Ion din Anina), the remains (the lower jaw) are approximately 37,800 years old.

These are some of Europe’s oldest remains of Homo sapiens, so they are likely to represent the first such people to have entered the continent.[6] According to some researchers, the particular interest of the discovery resides in the fact that it presents a mixture of archaic, early modern human and Neanderthal morphological features,[7] indicating considerable Neanderthal/modern human admixture,[8] which in turn suggests that, upon their arrival in Europe, modern humans met and interbred with Neanderthals. Recent reanalysis of some of these fossils has challenged the view that these remains represent evidence of interbreeding.[9] A second expedition by Erik Trinkaus and Ricardo Rodrigo, discovered further fragments (for example, a skull dated ~36,000, nicknamed "Vasile").

Two human fossil remains found in the Muierii (Peştera Muierilor) and the Cioclovina caves in Romania have been radiocarbon dated using the technique of the accelerator mass spectrometry to the age of ~ 30,000 years BP (see Human fossil bones from the Muierii Cave and the Cioclovina Cave, Romania).

The first skull, scapula and tibia remains were found in 1952 in Baia de Fier, in the Muierii Cave, Gorj County in the Oltenia province, by Constantin Nicolaescu-Plopşor.

In 1941 another skull was found at the Cioclovina Cave near Commune Bosorod, Hunedoara County, in Transylvania. The anthropologist, Francisc Rainer, and the geologist, Ion Th. Simionescu, published a study of this skull.

The physical analysis of these fossils was begun in the summer of the year 2000 by Emilian Alexandrescu, archaeologist at the Vasile Pârvan Institute of Archaeology in Bucharest, and Agata Olariu, physicist at the Institute of Physics and Nuclear Engineering-Horia Hulubei, Bucharest, where samples were taken. One sample of bone was taken from the skull from Cioclovina; samples were also taken from the scapula and tibia remains from Muierii Cave. The work continued at the University of Lund, AMS group, by Göran Skog, Kristina Stenström and Ragnar Hellborg. The samples of bones were dated by radiocarbon method applied at the AMS system of the Lund University and the results are shown in the analysis bulletin issued on the date 14 December 2001.

The human fossil remains from Muierii Cave, Baia de Fier, have been dated to 30,150 ± 800 years BP, and the skull from the Cioclovina Cave has been dated to 29,000 ± 700 years BP.[10][11][12]

Mesolithic

- (9,500 – 7,500 BP)

The Mesolithic period began at the end of the Pleistocene epoch (10th millennium BC) and ended with the Neolithic introduction of farming, the date of which varied in each geographical region. According to Douglass W. Bailey:[13]

| “ | It is equally important to recognize that the Balkan upper Palaeolithic was a long period containing little significant internal change. The Mesolithic may not have existed in the Balkans for the same reasons that cave art and mobiliary art never appeared: the changes in climate and flora and fauna were gradual and not drastic. (…) Furthermore, one of the reasons that we do not distinguish separate industries in the Balkans as Mesolithic is because the lithic industries of the early Holocene were very firmly of a gradually developing late Palaeolithic tradition | ” |

The Mesolithic is the transitional period between the Upper Palaeolithic hunter-gathering existence and the development of farming and pottery production during the Postglacial Neolithic. The duration of the classical Palaeolithic, which lasted until about 10,000 years ago, is applicable to the Balkans. It ended with the Mesolithic (duration is two to four millennia) or, where an early Neolithisation was peculiar to, with the Epipalaeolithic.

Regions with limited glacial impact (e.g. the Balkans), the term Epipalaeolithic is more preferable. Regions that experienced less environmental effects during the last ice age have a much less apparent, straightforward, and occasionally marked by an absence of sites from the Mesolithic era. See the above Douglass W. Bailey quote.

There is lithic evidence in Serbia (see Lepenski Vir), southwestern Romania, and Montenegro. At Ostrovul Banului, the Cuina Turcului rock shelter in the Danube Gorges and in the nearby caves of Climente people make relatively advanced bone and lithic tools (i.e. end-scrapers, blade lets, and flakes).

The single site representing materials related to Mesolithic in Bulgaria is Pobíti Kámǎni. There is no another lithic evidence on the period. There is a 4,000-gap between the latest Upper Palaeolithic material (13,600 BP at Témnata Dupka) and the earliest Neolithic evidence presented at Gǎlǎbnik (the beginning of the 7th millennium BC).

At Odmut in Montenegro there is evidence for human activity in the period. The research of the period was supplemented with Greek Mesolithic well represented by sites such as Frachthi Cave. The other sites are Theopetra Cave and Sesklo in Thessaly that represent the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic as well as the early Neolithic period. Yet southern and coastal sites Greece, which contained materials from the Mesolithic are less known.

Activities began to be concentrated around individual sites where people displayed personal and group identities using various decorations: wearing ornaments and painting their bodies with ochre and hematite. As regards the point of identity D. Bailey writes, “Flint-cutting tools as well as time and effort needed to produce such tools testify the expressions of identity and more flexible combinations of materials, which began to be used in the late Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic.”

The aforementioned allows us to speculate whether or not there was a period which could be described as Mesolithic in southeastern Europe, rather than an extended Upper Palaeolithic. On the other hand, lack of research in a number of regions, and the fact that many of the sites were close to the shore (it is evident that the current sea level is 100 m higher, and a number of sites were covered by water) means that Mesolithic Balkans could be referred to as Epipalaeolithic) Balkans which would better describe its gradual continuity and poorly defined development.

The relative climatic stability in the Balkans, compared to northern and western Europe, enabled continuous settlement in the Balkans, thus effectively functioning as an ice-age refuge from where much of Europe, especially eastern Europe, was re-populated.

Neolithic

The Balkans were the site of major Neolithic cultures, including Butmir, Vinča, Varna, Karanovo, Hamangia.

The Vinča culture was an early culture of the Balkans (between the 6th and the 3rd millennium BC), stretching around the course of the Danube in Serbia, Croatia, northern parts of Bosnia and Montenegro, Romania, Bulgaria, Kosovo, Albania the Republic of Macedonia, although traces of it can be found all around the Balkans, parts of Central Europe and Asia Minor.

"Kurganization" of the eastern Balkans (and the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture adjacent to the north) during the Eneolithic is associated with an early expansion of Indo-Europeans.

- Butmir culture

- Starčevo-Criş culture

- Dudeşti culture

- Cucuteni-Trypillian culture

- Hamangia culture

- Vinča culture

- Varna culture

- Tărtăria tablets

- Kurgan hypothesis

Bronze Age

- (3,500 – 1,100 BC)

The Bronze Age in the Balkans is divided as follows (Boardman p. 166)

- Early Bronze Age: 20th to 16th centuries BC

- Middle Bronze Age: 16th to 14th centuries BC

- Late Bronze Age: 14th to 13th centuries BC

The Bronze Age in the Central and Eastern Balkans begins late, around 1800 BC. The transition to the Iron Age gradually sets in over the 13th century BC.

The "East Balkan Complex" (Karanovo VII, Ezero culture) covers all of Thrace. The Bronze Age cultures of the Central and Western Balkans are less clearly delineated and stretch to Pannonia, the Carpathians and into Hungary.

Iron Age

After the period that followed the arrival of the Dorians, known as the Greek Dark Ages or Submycenaean Period, the classical Greek culture began to develop in the southern Balkan peninsula, the Aegean islands and the western Asia Minor Greek colonies starting around the 9–8th century (the Geometric Period) and peaking with the 5th century BC Athens democracy.

The Greeks were the first to establish a system of trade routes in the Balkans and, in order to facilitate trade with the natives between 700 BC and 300 BC, they founded several colonies on the Black Sea (Pontus Euxinus) coast, Asia Minor, Dalmatia, Southern Italy (Magna Graecia) etc.

The other peoples of the Balkans organized themselves in large tribal unions such as the Thracian Odrysian kingdom in the Eastern Balkans in the 5th century BC, and the Illyrian kingdom in the Western Balkans from the early 4th century.

Other tribal unions existed in Dacia at least as early as the beginning of the 2nd century BC under King Oroles. The Illyrian tribes were situated in the area corresponding to today's former Yugoslavia and Albania. The name Illyrii was originally used to refer to a people occupying an area centred on Lake Skadar, situated between Albania and Montenegro (see List of ancient tribes in Illyria). The term Illyria was subsequently used by the Greeks and Romans as a generic name to refer to different peoples within a well defined but much greater area.[14]

Hellenistic culture spread throughout the Macedonian Empire created by Alexander the Great from the later 4th century BC. By the end of the 4th century BC Greek language and culture were dominant not only in the Balkans but also around the whole Eastern Mediterranean.

By the 6th century BC the first written sources dealing with the territory north of the Danube appear in Greek sources. By this time the Getae (and later the Daci) had branched out from the Thracian-speaking populations.

See also

- Aegean civilization

- Bronze Age Europe

- Dacia

- History of Eurasia

- History of Europe

- Illyria

- Iron Age Europe

- Mesolithic Europe

- Neolithic Europe

- Old European culture

- Paleo-Balkans languages

- Paleolithic Europe

- Prehistory of Transylvania

- Bronze Age in Romania

- Prehistoric Croatia

- Prehistoric Europe

- Prehistoric Serbia

- Prehistory

- Proto-Indo-Europeans

- Stone Age

- Thracia

- Thracian language

- Timeline of glaciation

References

- Inline

- ↑ Classical World

- ↑ e.g. Thrace in book V.

- ↑ http://www.academia.edu/400095/Sirakov_et_al._2010_.-_An_ancient_continuous_human_presence_in_the_Balkans_and_the_beginnings_of_human_settlement_in_western_Eurasia_A_Lower_Pleistocene_example_of_the_Lower_Palaeolithic_levels_in_Kozarnika_cave_North-western_Bulgaria_

- ↑ Balkan prehistory Page 15 By Douglass W. Bailey ISBN 0-415-21597-8

- ↑ Trinkaus, E., Milota, Ş., Rodrigo, R., Gherase, M., Moldovan, O. (2003), Early Modern Human Cranial remains from the Peştera cu Oase, Romania in Journal of Human Evolution, 45, pp. 245 –253,

- ↑ João Zilhão, (2006), Neanderthals and Moderns Mixed and It Matters, in Evolutionary Anthropology, 15:183–195, p.185

- ↑ Trinkaus, E., Moldovan, O., Milota, Ş., Bîlgăr, A., Sarcina, L., Athreya, S., Bailey, S.E., Rodrigo, R., Gherase, M., Hilgham, T., Bronk Ramsey, C., & Van Der Plicht, J. ( 2003), An early modern human from Peştera cu Oase, Romania. Proceedings of the National Acadademy of Science U.S.A., 100(20), pp. 11231–11236

- ↑ Andrei Soficaru, Adrian Dobo and Erik Trinkaus (2006), Early modern humans from the Peştera Muierii, Baia de Fier, Romania, Proceedings of the National Acadademy of Science U.S.A., 103(46), pp. 17196-17201

- ↑ Harvati K, Gunz P, Grigorescu D. Cioclovina (Romania): affinities of an early modern European. J Hum Evol. 2007 Dec;53(6):732-46

- ↑ Olariu A., Alexandrescu E., Skog G., Hellborg R., Stenström K., Faarinen M. and Persson P, Dating of two Palaeolithic human fossil bones from Romania by accelerator mass spectrometry, NIPNE Scientific Reports 2001-202, pag. 82

- ↑ Olariu A., Skog G., Hellborg R., Stenström K., Faarinen M. and Persson P. and Alexandrescu E., 2003, Dating of two Palaeolithic human fossil bones from Romania by accelerator mass spectrometry, http://arXiv.org/abs/physics/0309110

- ↑ Olariu A., Stenström K. and Hellborg R. (Eds), 2005, Proceedings of International conference on Applications of High Precision Atomic & Nuclear Methods, 2–6 September 2002, Neptun, Romania, Publishing House of Romanian Academy, Bucharest, ISBN 973-27-1181-7, Dating of two Palaeolithic human fossil bones from Romania by accelerator mass spectrometry, 235-239

- ↑ Balkan prehistory Page 36 By Douglass W. Bailey ISBN 0-415-21597-8

- ↑ The Illyrians. John Wilkes

- General

- John Boardman, The Cambridge Ancient History, Part I: The Prehistory of the Balkans to 1000 BC, Cambridge University Press (1923), ISBN 0-521-22496-9.

- Douglass W. Bailey, Balkan prehistory, ISBN 0-415-21597-8

- Alexandru Păunescu, Evoluţia istorică pe teritoriul României din paleolitic până la inceputul Neoliticului, SCIVA, 31, 1980, 4, p. 519-545.

- Paul Lachlan MacKendrick, The Dacian Stones Speak, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1974, ISBN 0-8078-4939-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |

- Periodization of Balkan Prehistory ~ 6200 - 1100 BC

- South East Europe pre-history summary to 700BC

- Balkan Prehistory: Exclusion, Incorporation and Identity by Douglass W. Bailey

- The Aegeo-Balkan Prehistory Project

- (Romanian) Ion din Anina, primul om din Europa on Jurnalul.ro

- (English) Human fossils set European record on BBC.co.uk

- (Romanian) Enciclopedia României