James Cameron (activist)

James Cameron (February 25, 1914 – June 11, 2006) was an American civil rights activist. In the 1940s, he founded three chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).[1] He also served as Indiana's State Director of the Office of Civil Liberties from 1942 to 1950.

In the 1950s he moved with his family to Wisconsin, where he continued as an activist and started speaking on African-American history. In 1988 he founded America's Black Holocaust Museum in Milwaukee, devoted to African-American history from slavery to the present.

At his death, Cameron was the only known survivor of a lynching attempt.[1]

Early life and education

Cameron was born February 25, 1914, in La Crosse, Wisconsin, to James Herbert Cameron and Vera Carter. After his father left the family, they moved to Birmingham, Alabama, then to Marion, Indiana. When James was 14, his mother remarried.

Arrest and attempted lynching

In August 1930, when Cameron was 16 years old, he and two older teenage friends, Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, were charged in Marion with the murder of a young white man, Claude Deeter, during an armed robbery attempt, and with the rape of his girlfriend. (The latter charge was dropped.) Cameron said he ran away before the man was killed.[1][2] The three were caught quickly and arrested and charged the same night with robbery, murder and rape.

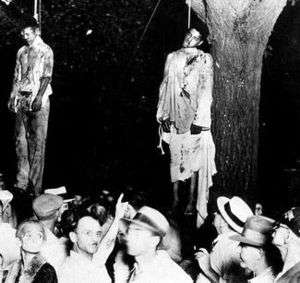

A lynch mob broke into the jail where Cameron and his two friends were being held. According to Cameron's own account, the two older boys were taken out first, beaten and lynched by a mob of 12,000–15,000 at the Grant County Courthouse Square. Shipp was taken out and beaten, hanged from the bars of his jail window; Smith was dead from beating before the mob hanged both the boys from a tree in the square.[1][2] Cameron was beaten and a noose was put around his neck; before he was hanged, the voice of an unidentified woman intervened, saying that he was not guilty. He was returned to the jail. Cameron said his neck was scarred from the rope.

Mrs. Flossie Bailey, a local NAACP official, and the State Attorney General worked to gain indictments against leaders of the mob in the lynchings but were unsuccessful. No one was ever charged in the murders of Shipp and Smith nor the assault on Cameron.[3]

Cameron was convicted at trial in 1931 as an accessory before the fact to the murder of Deeter and served four years of his sentence in a state prison. After he was paroled, Cameron moved to Detroit, Michigan, where he worked at Stroh Brewery Company and attended Wayne State University.[4]

In 1991, Cameron was pardoned by the state of Indiana.[4]

Career

Cameron studied at Wayne State University to become a boiler engineer and worked until he was 65. At the same time, he continued to study lynchings, race and civil rights in America and trying to teach others.

Because of his personal experience, Cameron dedicated his life to promoting civil rights, racial unity and equality. While he worked in a variety of jobs in Indiana during the 1940s, he founded three chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). This was a period when the Ku Klux Klan was still active in the Midwest, although its numbers had decreased since its peak in the 1920s. Cameron established and became the first president of the NAACP Madison County chapter in Anderson, Indiana.[1]

He also served as the Indiana State Director of Civil Liberties from 1942 to 1950. In this capacity, Cameron reported to Governor of Indiana Henry Schricker on violations of the “equal accommodations” laws designed to end segregation. During his eight-year tenure, Cameron investigated more than 25 incidents of civil rights infractions. He faced violence and death threats because of his work.

Civic activism

By the early 1950s, the emotional toll of threats led Cameron to search for a safer home for his wife and five children. Planning to move to Canada, they decided on Milwaukee when he found work there. There Cameron continued his work in civil rights by assisting in protests to end segregated housing in the city. He also participated in both marches on Washington in the 1960s, the first with Martin Luther King, Jr., and the second with King’s widow Coretta and Jesse Jackson.

Cameron studied history on his own and lectured on the African-American experience. From 1955 to 1989 he published hundreds of articles and booklets detailing civil rights and occurrences of racial injustices, including "What is Equality in American Life?"; "The Lingering Problem of Reconstruction in American Life: Black Suffrage"; and "The Second Civil Rights Bill".[5] In 1982 he published his memoir, A Time of Terror: A Survivor's Story.

After being inspired by a visit with his wife to the Yad Vashem memorial in Israel, Cameron founded America's Black Holocaust Museum in 1988. He used material from his collections to document the struggles of African Americans in the United States, from slavery through lynchings, and the 20th-century civil rights movement. When he first started collecting materials about slavery, he kept it in his basement. Working with others to build support for the museum,[1] he was aided by philanthropist Daniel Bader.[4]

The museum started as a grassroots effort and became one of the largest African-American museums in the country. In 2008, the museum closed because of financial problems. It reopened on Cameron's birthday, February 25, 2012, as a virtual museum.

Personal life

Cameron and his wife, Virginia Hamilton, had five children. He died on June 11, 2006, at the age of 92, from congestive heart failure.[1] He is buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Milwaukee. Two sons, David and James, had died before him.[6] He was survived by his wife Virginia and three children: Virgil, Walter, and Dolores Cameron, and numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren.[1]

Legacy and honors

- Wisconsin Public Television produced a documentary entitled A Lynching in Marion.[6]

- Marion, Indiana presented Cameron with a key to the city.[6]

- Cameron was interviewed by BBC, and Dutch and German television.[6]

- In 1999 Cameron was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee.[7]

- Milwaukee added his name to four blocks of West North Avenue, from North King Drive to North 7th Street.[8]

Published works

- Cameron, James. A Time of Terror: A Survivor’s Story, self-published, 1982; reprinted Black Classics Press, 1994.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Yvonne Shinhoster Lamb, "Obituary of James Cameron", The Washington Post, 12 June 2006, accessed 14 July 2008

- 1 2 David Bradley, "Anatomy of a Murder: Review of Cynthia Carr's Our Town", The Nation, 24 May 2006, accessed 06 September 2015.

- ↑ Monroe H. Little, Review of James Madison's A Lynching in the Heartland, History-net, accessed 11 June 2014

- 1 2 3 James Cameron Holocaust Museum founder, African American Registry, 2006, accessed 15 July 2008

- ↑ "Our Founder", America's Black Holocaust Museum, accessed 15 July 2008

- 1 2 3 4 Meg Jones, Leonard Sykes, Jr., and Amy Rabideau Silvers, "Cameron brought light to racial injustices", Milwaukee Sentinel Journal, 11 June 2006, accessed 15 July 2008

- ↑ "Director of America's Black Holocaust Museum to Speak at MSU", Michigan State University News, 11 September 2003, accessed 15 July 2008 Archived May 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Sandler, Larry (2006-08-30). "Street could be renamed for good Samaritan who died". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Further reading

- Allen, James; Hilton Als, et al., Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America (Twin Palms Publishers, 2000).

- Carr, Cynthia, Our Town: A Heartland Lynching, A Haunted Town, and the Hidden History of White America, Random House, 2007.

- Tolnay, Stewart E. and E. M. Beck, A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings, 1882-1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992)

External links

- America's Black Holocaust Museum

- "Obituary of James Cameron" - Washington Post

- James Cameron's oral history video excerpts, The National Visionary Leadership Project

- David J. Marcou. "Challenger & Nurturer: Wisconsin Civil Rights Pioneer James Cameron (1914-2006)", La Crosse History