James Rossant

| James Rossant | |

|---|---|

|

Lake Anne in Reston | |

| Born |

James Stephan Rossant August 17, 1928 New York City, US |

| Died |

December 15, 2009 (aged 81) Condeau, France |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouse(s) | Colette Rossant |

| Children | Marianne, Juliette, Cecile, Tomas |

| Website |

jamesrossant |

| Buildings | Butterfield House, Myriad Botanical Gardens, Ramaz School, Two Charles Center, U.S. Navy Memorial |

James Stephan Rossant (August 17, 1928 – December 15, 2009) was an American architect, artist, and professor of architecture.[1][2][3][4]

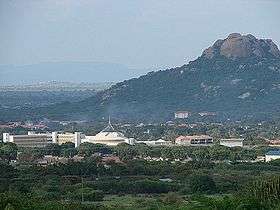

A long-time Fellow of the American Institute of Architects,[5] he is best known for his master plan of Reston, Virginia, the Lower Manhattan Plan, and the UN-sponsored master plan for Dodoma, Tanzania. He was a partner of the architectural firm Conklin & Rossant and principal of James Rossant Architects.[1][2][3][4]

Early life

Born in Sydenham Hospital, New York City, Rossant grew up in the Bronx, where he attended the Bronx High School of Science.[3][4] He studied architecture at Columbia University, the University of Florida, and Harvard University's Graduate School of Design (under Walter Gropius).[1][3]

Career

Almost immediately following university, Rossant served in Europe during the Korean War.

Architecture

After the war, he worked in Italy with Gino Valle (designer of the Cifra 3 clock).[1]

In 1957, Rossant joined Mayer & Whittlesey as architect and town planner.[1][2] His first large design project was the Butterfield House apartment house in Greenwich Village (1962). He also worked on the Lower Manhattan Plan.[1][3]

For Whittlesey & Conklin, he developed the master plan for Reston, Virginia.[2][3][4]

For Conklin & Rossant his work includes the Crystal Bridge of the Myriad Botanical Gardens (Oklahoma City),[6] the Ramaz School (New York City),[7] Two Charles Center (Baltimore), and the U.S. Navy Memorial at Market Square (Washington, DC).[2][3][8][9]

For 3R Architects, his work includes Tanzania's new capital at Dodoma under the sponsorship of the United Nations.[10] He served on New York City's Public Design Commission (formerly the Art Commission of the City of New York).[2]

On November 2, 1971, Rossant appeared with Ada Louise Huxtable on the television show Firing Line on discuss "Why Aren't Good Buildings Being Built?".[11] He appears posthumously from television clips and his wife in interviews as part of Rebekah Wingert-Jabi's 2015 documentary Another Way of Living: The Story of Reston, VA.[12][13]

Artwork

Rossant painted all his life and exhibited frequently (last in Paris, 2009).[14] His sculpture includes work publicly accessible on Washington Plaza along Lake Anne in Reston. He published Cities in the Sky in 2009, based on one of his longest series of architectural paintings.[1][4] He also illustrated several cookbooks by his wife.[15][16]

Teaching

Rossant taught architecture at the Pratt Institute (1970–2005) and Urban Design at New York University's School of Public Administration (1975–1983). As lecturer, he visited the National University of Singapore, the American University of Beirut, Harvard University, the University of Virginia, and Columbia University.[1][17]

Personal and death

Rossant's brother was the journalist Murray Rossant.

He married Colette Palacci while serving in the army in Europe; the couple moved back the US in the mid-1950s. The couple had four children.

He died near Condeau in the Orne portion of Le Perche, Lower Normandy, France, of complications arising from long-term, chronic lymphonic leukemia or CLL.[1][2][3][4][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29]

Rossant was survived by his wife Colette Rossant (food critic, cookbook author, memoirist); children Marianne (educator), Juliette (author and journalist), Cecile (author and architect), and Tomas (architect); and eight grandchildren.[1][3]

His nephew is John Rossant, founder of the New Cities Foundation (a global non-profit focused on the future of cities). His cousin is the British psychotherapist, Susie Orbach.

Works

James Rossant wrote a memoir which he published privately and shared with members of his family.

Writings:

- Willis, Carol, ed. (2002). Lower Manhattan Plan: The 1966 vision for downtown New York: Essays by Ann Buttenwieser, Paul Willen, and James Rossant. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- Rossant, James (6 August 2009). Cities in the Sky. San Francisco: Blurb. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- Articles (various)[30]

Drawings:

- Rossant, Colette (1975). Cooking with Colette, with drawings by James Rossant. New York: Scribner. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- Rossant, Colette (1983). Colette's Slim Cuisine, with drawings by James S. Rossant. New York: Morrow. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Biering, Alexander (January 12, 2010). "James Rossant, Noted Architect and Planner, Dies at 81". Architectural Record. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Krouse, Sarah (December 15, 2009). "James Rossant, master planner behind Reston, Dies". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Grimes, William (December 18, 2009). "James Rossant, Architect and Planner, Dies at 81". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Champenois, Michele (December 26, 2009). "James Rossant, architecte et urbaniste americain". Le Monde. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- ↑ "James Stephan Rossant". American Institute of Architects - Directory. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "Myriad Gardens". JamesRossant.com. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Ramaz School". JamesRossant.com. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ↑ "U.S. Navy Memorial". JamesRossant.com. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site" (PDF). US DOI - NPS: National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "Dodoma". JamesRossant.com. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Inventory of the Firing Line (Television Program) Broadcast Records". Online Archive of California (OAC). Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ "Another Way of Living: The Story of Reston, VA". IMDB. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ "Another Way of Living: The Story of Reston, VA" (PDF). Another Way of Living: official site. 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ "Artwork". JamesRossant.com. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ↑ "In Memoriam: James Rossant". Super Chef. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Illustrator". JamesRossant.com. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Lecturer". JamesRossant.com. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ↑ "James Rossant, Helped Design Reston VA". Boston Globe. 20 December 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "Hyperion No. 15 (dedicated to James Rossant)" (PDF). Nietzsche Circle. 1 May 2010. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "In Memoriam: James Rossant (1928–2009)" (PDF). Gateway (Pratt Institute). 27 February 2010. p. 2. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "James Rossant". Greater Reston Chamber of Commerce. January 2010. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "Farewell: James Rossant". ArtInfo. 23 December 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ Sigrist, Peter (23 December 2009). "In Memory of James Rossant (1928-2009)". Polis. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "James Rossant". Harvard Graduate School of Design. 19 December 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "James Rossant". Modern Capital. 19 December 2009.

- ↑ "In Memoriam: James Rossant". Super Chef. 19 December 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "James Rossant". Herndon Observer. 19 December 2009.

- ↑ "Hats Off: Reston Original Master Planner Dies at 81". Restonian. 16 December 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "James Rossant". Le Perchoir. 15 December 2009.

- ↑ "Writings". James Rossant. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

External links

- JamesRossant.com

- AIA New York Chapter