Joseph-François Mangin

| Joseph-François Mangin | |

|---|---|

| Born |

1758 Dompaire, France |

| Nationality | French-american citizen |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Practice | Architect |

| Buildings | St. Patrick's Old Cathedral |

| Projects | 1803 Plan for New York (with Casimir Goerck), rejected |

| Design | New York City Hall (1801-1802, with John McComb Jr.) |

Joseph-François Mangin was born on June 10, 1758 in Dompaire,[1] in the Vosges region of France. He was a French-American architect who is noted for designing New York City Hall and St. Patrick's Old Cathedral in New York City.

There is no information regarding his date or place of death.

Early life

Joseph Francois Mangin was born on June 10, 1758 in. Chalon Sir, France Dompaire in the Vosges region of France, the son of Jean-Baptiste François Mangin, the king's surgeon, and Marie Anne Milot, both from Dompaire. He studied Architecture in Paris, and Law at the University of Nancy, where he graduated in 1781[2] after leaving with his fiance' Fayeweather they sailed to NYC, where they married.. He became a surveyor for NYC, followed by becoming the architect of NYC Hall, a school, St Patrick's original Cathedral ,his business partner John McComb was the builder of city hall. Joseph was a Military engineer during the war of 1812; designing the levy around NYC to prevent enemy ships from entering the harbor. Joseph and Fayeweather had two children;"John and Lawrence". His brother Charles had one Son "Charles"; whose son received the distinguished Medal of honor as General Charles Mangin. He became a naturalized American citizen in 1796.[3]

Career

In New York, Mangin became a protegé of Alexander Hamilton, and, due to Hamilton's influence, Mangin was hired by the federal government to design fortifications for New York harbor. He also designed the city's first theatre in 1795, and the first prison for New York state, in the village of Greenwich on the Hudson River, which would, when subsumed by the growth of the city, become Greenwich Village.[4]

Mangin was appointed to be one of the handful of official recognized "city surveyors", he was a Military Engineer during the war of 1812 the United States. Mangin was at pains to point out to Hamilton his love for and allegiance to his adopted country: "I am an American, and the last drop of my blood will be shed in the service of my country."[5]

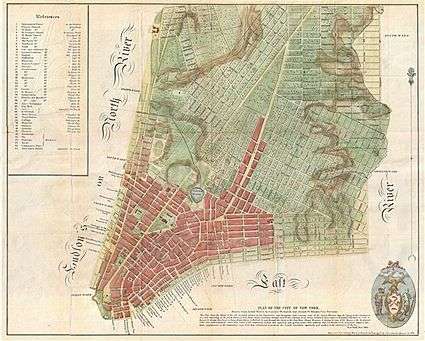

Prior to the New York City Commissioner’ Plan of 1811, the city's Common Council in 1797 commissioned city surveyors Casimir Goerck and Mangin to survey the streets of the city; Goerck and Mangin had each submitted individual proposals to the Council, but then decided to team up. Goerck died of yellow fever during the course of the surveying, but Mangin completed it and delivered the draft of the Mangin-Goerck Plan to the Council in 1799 for correction of street names; the final engraved version would be presented to the Council in 1803. Unfortunately, Mangin had gone beyond the terms of the commission, and the map not only showed the existing streets of the city, but also, in Mangin's words, "the City ... such as it is to be..." In other words, the plan was a guide to where Mangin believed future streets should be laid out.

The Council accepted the Mangin-Goerck Plan as "the new Map of the City" for four years, and even published it by subscription, until political machinations perhaps organized by Aaron Burr, the political enemy of Mangin's mentor Alexander Hamilton, brought the plan into disrepute, and the Council ordered that copies which had already been sold be bought back, and that a label warning of "inaccuracies" be placed on any additional copies sold.[6][7][8] Nevertheless, as the city grew, the Mangin-Goerck Plan became the de facto reference for where new streets would be built, and when the Commissioners' Plan was revealed in 1811, the area of the plan which the public had been warned was innaccurate and speculative, had been accepted wholesale by the Commission, their plan being almost identical to Mangin's in that area.[9]

In 1802, Mangin and John McComb Jr- Builder. won a design contest to build New York's City Hall. The design, which was primarily Mangin's – Mangin was renowned as the talented designer, while McComb came from a family of talented builders – won out over a field of 25 other entries, including one from Benjamin Henry Latrobe Jr. – a protogé of Alexander Hamilton's political enemy, Aaron Burr – who would go on to be known as the "Father of American Architecture", but would never design a building in New York City.[10] Historian Gerard Koeppel speculates that it this snubbing of an architect from his circle for one from Hamilton's circle which was the cause of the downfall of the Mangin-Goerck Plan.[11]

Mangin would, for some time, be denied credit for his City Hall design: in 1803 the Common Council ordered some changes in the design. Perhaps because he disagreed with them, McComb supervised the work, and, as a result, the cornerstone for the building only listed McComb's name, and not Mangin's. Then in the 1890s, a descendent of McComb erased Mangin's name form the drawing they had submitted for the competition, so as to increase their value. In 1915, The New York Times, the city's "paper of record" accepted that McComb was the sole designer of the building, mentioning only that Mangin was "reputed" to have been associated with it. It wasn't until 2003 that Mangin's true role as the principle designer of City Hall was uncovered by research, and an official ceremony was held to unveil a new cornerstone with his name on it.[12]

.jpg)

In Spring 1807, Mangin sold his property in New York City and purchased a tract of land 1 mile (1.6 km)-square in upstate New York, in Madrid in St. Lawrence County. He went to live there, intending it to be his life-long residence, but returned to the city before the winter was out, getting back his old position as a city surveyor. He sought out military contracts, but did not get any.[13]

After his return to New York City, Mangin designed the First Presbyterian Church on Wall Street (1810), which was rebuilt twice before being taken apart and moved to Jersey City;[14][15] and the city's original Greek Revival-style St. Patrick’s Cathedral (1809-1815) at the corner of Mott and Prince Streets, which was altered after a fire in 1866 into a Gothic parish church, and was elevated to basilica status in 2010.[16]

Mangin's work as a surveyor encompassed locations not only in New York City, but in New Jersey and in upstate New York.[17]

Legacy

Mangin Street, as laid out in the Commissioner's Plans, ran from Grand Street north to Houston Street to the East River at Rivington Street, which was extended as landfill areas were incorporated into Manhattan, and now extends just west of the FDR Drive. During urban renewal projects, most of the street disappeared, except for two short stretches under the Williamsburg Bridge and from Baruch Place to East Houston Street.

Mangin Avenue in St. Albans, Queens may also have been named after Mangin.

Controversy

For many years, incorrect information circulated about Mangin's life. He was mistaken for another Joseph-François Mangin born in France around the same period, or was a slave, followed by becoming a student of one of the most prominent French architects, Ange-Jacques Gabriel. [genealogical research conducted by his descendants for many generations.

References

Notes

- ↑ "Edpt153/GG_10-25607 - 1757-1758 - Archives départementales des Vosges". www.archives-recherche.vosges.fr. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ Archives Départmentales de Meuthe-et-Moselle, Cote 3 B XXI art. 7

- ↑ Koeppel (2015), p.31

- ↑ Koeppel (2015), pp.29-30

- ↑ Koeppel (2015), pp.31-32

- ↑ Koeppel (2015), pp.37-41;51-56

- ↑ Koeppel, Gerard (August 01–07, 2007) "Talking Point: Manhattan traffic congestion is a historic mistake", The Villager. Accessed: 19 May 2011

- ↑ Gray, Christopher (October 23, 2005). "Streetscapes - The Commissioners' Plan of 1811: Are Manhattan's Right Angles Wrong?". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ↑ Koeppel (2015), p.60

- ↑ Koeppel (2015), pp.41-42

- ↑ Koeppel (2015), pp.51-52

- ↑ Koeppel (2015), p.62

- ↑ Koeppel (2015), pp.90-91

- ↑ Koeppel (2015), p.30

- ↑ Dunlap, David W. (2004). From Abyssinian to Zion: A Guide to Manhattan's Houses of Worship. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12543-7., pp.76-77

- ↑ McFadden, Robert D. (December 5, 2010) "Cathedral With a Past; Basilica With a Future" The New York Times

- ↑ Koeppel (2015), p.63

Bibliography

- Koeppel, Gerard (2015), City on a Grid: How New York Became New York, Boston: Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-0-306-82284-1