Juan Mari Brás

| Juan Mari Brás | |

|---|---|

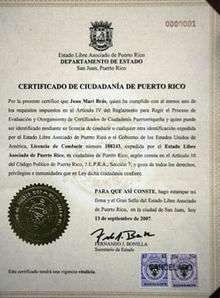

Mari Brás after receiving the first Certificate of Citizenship of Puerto Rico, September 14, 2007 | |

| Born |

December 2, 1927 Mayagüez, Puerto Rico |

| Died |

September 10, 2010 (aged 82) San Juan, Puerto Rico |

| Nationality |

Puerto Rican |

| Organization | Puerto Rican Socialist Party (PSP) |

Juan Mari Brás (December 2, 1927 – September 10, 2010)[1] was an advocate for Puerto Rican independence from the United States who founded the Puerto Rican Socialist Party (PSP). On October 25, 2006, he became the first person to receive a Puerto Rican citizenship certificate from the Puerto Rico State Department.

Early years

Juan Mari Brás was born in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico. His father was active in the independence movement who often took his son to political meetings and rallies. In 1943, when he was 18 years old, he founded a pro-independence movement in his high school, along with some of his friends, in Mayagüez. He was also the founder and director of the first pro-independence political radio program "Grito de la Patria".

Student activist

In 1944, he enrolled in the University of Puerto Rico (Universidad de Puerto Rico) and in 1946 became a founding member of Gilberto Concepción de Gracia's Puerto Rican Independence Party. Mari Brás became the president of the party's "Puerto Rican Independence Youth". In 1948, the university's pro-independence student body invited nationalist leader Pedro Albizu Campos to the Río Piedras campus as a guest speaker. The chancellor of the university, Jaime Benítez, did not permit Albizu access to the campus. As a consequence, the students protested and went on strike. Mari Brás was one of the student leaders who chanted anti-American slogans and who marched with a Puerto Rican flag in his hand. Both of these acts were considered as acts against the Government of the United States, which at that time had complete control of the government of the island. Mari Brás and others who protested were expelled from the university.[2]

Mari Brás moved to Lakeland, Florida, where he earned his bachelor's degree.[3] He later studied at Georgetown University. In 1954, he went to study law at George Washington University Law School but was expelled[4] and finally obtained his law degree from American University.

Political career

Pro-Independence Movement

In 1959, Mari Brás founded the Pro-Independence Movement, which grouped Puerto Rican independence followers who supported the Socialist philosophy. Along with César Andreu Iglesias he founded the political newspaper Claridad, which he directed for three decades. In 1971, the Pro-Independence Movement was renamed and became the Puerto Rican Socialist Party (PSP). In 1973, he spoke before the United Nations about Puerto Rico being a colony of the United States and demanded the decolonization of the island. He was the first Puerto Rican to raise this issue before that forum.[5] On March 1976, one of Mari Brás' sons, Santiago Mari Pesquera, was murdered while his father was campaigning for governor on the Socialist Party ticket. Police investigations have hinted that Mari Pesquera was assassinated in reprisal for his father's political activism. The murder has never been officially solved.[5]

After losing the governorship and his son, Mari Bras continued to dedicate his time to campaigning for the independence of Puerto Rico. He was a prolific writer as well as a speaker before various audiences on the issue of the political status of Puerto Rico. He founded the Puerto Rican Socialist Party and was a co-founder of the small but influential Puerto Rican Independence Party. Professionally he performed as a law professor at the Eugenio María de Hostos School of Law in Puerto Rico.[5]

U.S. citizenship renunciation

On July 11, 1994, Mari Brás renounced his American citizenship at the American Embassy in Caracas, Venezuela. "He did this to test a technicality in United States citizenship laws.", according to writer Mary Hilaire Tavenner[6] Brás believed that a person holding United States citizenship and who subsequently renounces his citizenship would be deported to his country of origin. As Puerto Rico is a territory of the United States, Brás theorized the U.S. Department of State would have to deport him or any Puerto Rican who renounced his or her U.S. citizenship[6] to Puerto Rico. The U.S. State Department approved Mari Brás' renunciation of his American citizenship on November 22, 1995.[7]

On 15 May 1996, Miriam J. Ramírez de Ferrer, a pro-statehood attorney, presented a formal complaint against Mari Brás before the Mayaguez Electoral Board, where Mari Brás was registered to vote, so he could not vote as he was not a U.S. citizen. It was denied because the Board had no jurisdiction. Upon appeal by Ramírez, the Puerto Rico Electoral Board subsequently supported the decision of the Mayaguez Board. Ramírez subsequently took the matter to the Puerto Rico Superior Court (Tribunal de Primera Instancia, Sala Superior de San Juan). As a result, the Superior Court declared unconstitutional Articles 2.003 y 2.023 of Puerto Rico's Electoral Law as they required U.S. citizenship as a condition to vote in Puerto Rico's elections. On November 18, 1997, Ramírez then took Mari Brás before the Puerto Rico Supreme Court alleging that if he had renounced his United States citizenship, then he also had renounced his right to vote in the local Puerto Rican elections. The Puerto Rican Supreme Court sided with Mari Brás, finding that "as a citizen of Puerto Rico" Mari Brás was eligible to vote.[7]

In Lozada Colón v. U.S. Department of State (1998), the plaintiff was a United States citizen, born in Puerto Rico and resident of Puerto Rico, who executed an oath of renunciation before a consular officer at the U.S. Embassy in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. On April 23, 1998, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia held that the case was about "the much debated political question as to the status of Puerto Rico and its nationals in relation to the United States." It added that "While Plaintiff may well have strong political views with regard to Puerto Rican independence and the need for a citizenship separate and apart from the United States, this is not an issue for this Court to decide", and concluded that "the Plaintiff must seek another, more appropriate forum to express his political views."[8] These actions and rulings continue to be a popular subject of debate.[8][9]

In rejecting the renunciation, the Department noted that the Plaintiff in Colón demonstrated no intention of renouncing all ties to the United States, i.e., claiming to reject his United States citizenship, but nevertheless wishing to remain a resident of Puerto Rico. The Plaintiff's response was to claim a fundamental distinction between United States and Puerto Rican citizenship. The United States Department of State position asserted that renunciation of U.S. citizenship must entail renunciation of Puerto Rican citizenship as well. The court does decide to not enter to the merits of the citizenship issue; however the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia rejected Colón's petition for a writ of mandamus directing the Secretary of State to approve a Certificate of Loss of Nationality in the case because the plaintiff wanted to retain one of the primary benefits of U.S. citizenship while claiming he was not a U.S. citizen. The Court described the plaintiff as a person, "claiming to renounce all rights and privileges of United States citizenship, [while] Plaintiff wants to continue to exercise one of the fundamental rights of citizenship, namely to travel freely throughout the world and when he wants to, return and reside in the United States." The court based this decision on the Immigration and Nationality Act section 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(38), which defines the term "United States", and evince that Puerto Rico is a part of the United States for such purposes.[10]

In light of the Supreme Court's decision, on June 4, 1998, the U.S. State Department reversed its November 22, 1995 decision and declared that Mari Brás was still a US citizen. The U.S. State Department argued that as Mari Brás had continued living in a US territory, he was still a US citizen. According to the State Department, US Immigration and Naturalization law stipulates that anyone who wants to give up their US citizenship must live in another country.[11]

Based on the federal court ruling in Colón v. U.S. Department of State (1998), years after the U.S. State Department accepted his renunciation, Juan Mari Brás was notified on June 4, 1998, by the U.S. Department of State, that they were rescinding their acceptance, and refused to accept Mari Brás's renunciation, determining he could not renounce his United States citizenship as he did not request another national citizenship, and he was born and remains living and working in Puerto Rico.[12][13] Colón vs. U.S. Department of State became a landmark case and is posted on the U.S. State Department's webpage.[14]

Puerto Rican citizenship

After renouncing his American citizenship and over 10 years of litigation arguing he was a citizen of Puerto Rico, Mari Brás received the first certificate of Puerto Rican citizenship from the Puerto Rico Department of State. He stated "I freed myself from the indignity of a false citizenship ... that of the country that invaded mine, which continues to keep the only country that I owe allegiance to as a colony."[15]

The Supreme Court of Puerto Rico and the Puerto Rico Secretary of Justice determined that Puerto Rican citizenship exists and was recognized in the Constitution of Puerto Rico. Since the summer of 2007, the Puerto Rico State Department has developed the protocol to grant Puerto Rican citizenship to Puerto Ricans. Former Puerto Rico Supreme Court Associate Justice and former Secretary of State Baltasar Corrada questioned the legality of the certification, citing a law passed in 1997, authored by Kenneth McClintock Hernández, which establishes United States citizenship and nationality as a prerequisite for Puerto Rican citizenship.[16] Mari Bras' efforts generated vigorous public debate regarding the citizenship issue.[17]

Mari Brás is not the only Puerto Rican citizen to renounce his U.S. citizenship. Since Mari Brás' application, a number of other Puerto Rican citizens have also presented the required application papers before U.S. authorities to renounce their American citizenship.[18] According to The New York Times, "many other independentistas" followed in Mari Brás's footsteps and renounced their American citizenship as well.[19] The New York City-based El Diario-La Prensa reported in its April 30, 1998 edition that "thirteen more pro-independence Puerto Ricans had renounced their citizenship at the US embassy in the Dominican Republic on April 27 [1998]".[13][20]

Later years

Later in his life, Juan Mari Brás retired from active politics and no longer acted as president of the defunct Puerto Rican Socialist Party. He did continue to make appearances at pro-independence activities and continued to teach law at the Eugenio María de Hostos School of Law which he cofounded in his native Mayagüez over a decade ago. He dedicated his later years to seeking unity among the varied pro-independence factions in Puerto Rico and appeared before the United Nations on the political status issue.[5]

On December 10, 2008, he was recognized by the Puerto Rico chapter of the American Association of Jurists with the award of "Jurista del Año" ("Jurist of the Year").[21]

Death and legacy

Mari Brás died in San Juan on September 10, 2010. After hearing of Mari Brás's death the mayor of the city of Mayagüez, José Guillermo Rodríguez, decreed five days of mourning and ordered that flags in all municipal building be flown at half mast.[22] Mayor Rodríguez also announced that the city of Mayagüez would be collaborating with the Hostos School of Law in the funeral arrangements.[22] Following Mass at the Catedral Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria, Mari Brás was laid to rest at Cementerio Municipal de Mayagüez.

Quotes

| “ | Only through a great unified movement looking beyond political and ideological differences can the prevalent fears of hunger and persecution be overcome for the eventual liberation of Puerto Rico, breaking through domination by the greatest imperialist power of our age. — Juan Mari Brás[23] | ” |

See also

References

- ↑ Hevesi, Dennis (September 11, 2010). "Juan Mari Brás, Voice for Separate Puerto Rico, Dies at 82". The New York Times.

- ↑ Biografía de Juan Mari Brás (Spanish)

- ↑ Zwickel, Jean Willey. Voices for Independence: In the Spirit of Valor and Sacrifice. Portraits of Notable Individuals in the Struggle for Puerto Rican Independence. White Star Press (Pittsburg, California, U.S.) ISBN 0-9620448-0-6. March 1998, p. 98.

- ↑ Juan Mari Brás profile at peacehost.net/WhiteStar

- 1 2 3 4 Juan Mari Bras Obituary. Legacy.comRetrieved 27 September 2013.

- 1 2 Mary Hilaire Tavenner. Puerto Rico 2006: Memoirs of a Writer in Puerto Rico, p. 51. Xlibris Corporation (Lorain, Ohio: Dutch Ink Publishing; 2010); ISBN 978-1-4568-1003-0

- 1 2 97 DTS 135: Ramírez de Ferrer v. Mari Brás. Puerto Rico Supreme Court. MIRIAM J. RAMIREZ DE FERRER vs. Juan Mari Brás. November 18, 1997; retrieved July 18, 2012.

- 1 2 Lozada Colón v. U.S. Dept. of State 2 F.Supp.2d 43, (D.D.C., 1998) (later affirmed by "Lozada Colón v. U.S. Dept. of State", 170 F.3d 191 (C.A.D.C., 1999))

- ↑ Renunciation of U.S. Citizenship, U.S. Department of State; retrieved January 15, 2010.

- ↑ Renunciation of U.S. Citizenship. U.S. Department of State

- ↑ "US State Department Denies Puerto Rican Citizenship" Nicaragua Solidarity Network of Greater New York. New York, NY. "Weekly News Update on the Americas". Issue 437. June 14, 1998. (Quoted from: Agencia Informativa Pulsar, June 6, 1998; retrieved July 18, 2012.)

- ↑ *12. US State Department Denies Puerto Rican Citizenship, Nicaragua Solidarity Network of Greater New York. New York, N.Y. "Weekly News Update on the Americas." Issue 437. June 14, 1998. (Quoted from: El Diario-La Prensa. New York, N.Y., April 30, 1998; retrieved July 18, 2012.

- 1 2 Berrios: Decision on Mari Brás Shows P.R. is Still a Colony. Puerto Rico Herald. San Juan, Puerto Rico. Volume 2. Issue 10. (Originally published in The San Juan Star as "BERRIOS: DECISION ON MARI BRAS SHOWS P.R. STILL A COLONY", June 7, 1998); retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ↑ Renunciation of U.S. Citizenship, U.S. Department of State; retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ↑ Hevesi, Dennis (September 11, 2010). "Juan Mari Bras, Voice for Separate Puerto Rico, Dies at 82". New York Times.

- ↑ US citizenship a prerequisite to PR citizenship

- ↑ Supreme Court Denies Review Of Puerto Ricans' Citizenship, Puerto Rico Herald. Volume 3. Number 48. November 23, 1999; retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ↑ Trabas al Dimitir a la Ciudadania Estadounidense. Julio Ghigliotty. El Nuevo Día. December 31, 1997; retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ↑ Juan Mari Brás, Voice for Separate Puerto Rico, Dies at 82. Dennis Hevesi. The New York Times. September 11, 2010; retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ↑ US STATE DEPARTMENT DENIES PUERTO RICAN CITIZENSHIP Nicaragua Solidarity Network of Greater New York. New York, N.Y. "Weekly News Update on the Americas." Issue 437. June 14, 1998. (Quoted from: El Diario-La Prensa. New York, N.Y. April 30, 1998; retrieved July 18, 2012.)

- ↑ Profesor de la Facultad de Derecho Eugenio María de Hostos es reconocido como Jurista del Año. Facultad de Derecho Eugenio Maria de Hostos. Mayaguez, Puerto Rico. November 18, 2008. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- 1 2 Vargas, Maelo (September 10, 2010), "Cinco días de duelo y banderas a media asta en Mayagüez por la muerte de Juan Mari Brás", Primera Hora (in Spanish), retrieved September 10, 2010

- ↑ Voices for Independence: In the Spirit of Valor and Sacrifice: Portraits of Notable Individuals in the Struggle for Puerto Rican Independence. Jean Zwickel. White Star Press (Pittsburg, California, U.S.) ISBN 0-9620448-0-6; March 1998, p. 100; retrieved 18 July 18, 2012.

External links

- Juan Mari Brás

- Eugenio María de Hostos School of Law

- Portraits of Notable Individuals in the Struggle for Puerto Rican Independence