Jacques Triger

Jacques Triger (10 March 1801 – 16 December 1867)[1] was a French geologist who invented the 'Triger process' for digging through waterlogged ground.

Triger was also Deputy Director of coal mining operations in Chalonnes-sur-Loire (Maine-et-Loire).

Biography[2]

Triger was born in Mamers, a town in the Sarthe French county, on 10 March 1801. He studied at La Flèche and then in Paris, where he met Louis Cordier in 1825. Cordier was an eminent French geologist, who taught Triger his first lessons in geology. He was quickly interested in the technical challenges of this industrial sector. At 32 years old, together with skilled managers, he developed new industries in Sarthe and Mayenne. He developed and launched in this period three coal mines, a paper mill and a sawmill.

In 1833 he is left alone by the woman with whom he was supposed to get married. This disappointment in his personal life plunged him deeply into work: production of gravel from dolomite rock, construction of public fountains in Mamers and detailed study of phreatic groundwater tables near Le Mans.

About 1834 he started the study and the geological investigation of his region - Sarthe and Mayenne. He never stopped working on them until his death. These investigations, and discussions with Louis Cordier, drove him to Anjou (Maine-et-Loire)where coal was craft mined. Thus, in 1839, Triger seriously began to look at the Loire river and the way to reach solid rock underneath about 20 meters of water lodged soil. After having read many articles on compressed air, he was convinced that he could use it in order to dig trough this layer of soil. His success does not lie on the idea of using compressed air, but in the invention of the airlock - to pass from the compressed zone to the zone of ambient air pressure. And especially the finding of a practical way to utilize the technique on an industrial scale. With the financial and administrative support of Emmanuel de Las Cases, 5 steel tubes (the definitive shaft lining) were drilled by this invention, which was subsequently adapted and applied over and over again to dig foundations, bridges and many tunnels.

While focused on his industrial activities, he did not step away from his geological research work. Helped by a good taste for travels, pieces after pieces, he established the first geological map of the Sarthe county. After more than 20 years of research, the document was presented in 1853 at the Geological Society of France. The topographic background, support of the geological layers, was designed by Triger himself. To design this document, he had to study all the fossils in his county and deal with some of the mysteries at that time - such as the structure of the Cretaceous terrain of Maine, or the study of the Silurian-Devonian-Carboniferous lands in the West part of France.

Triger wanted the designation of the geological strata to be borrowed from paleontology (fossils names). He saw in this new system "the precious advantage of a universal language that one would understand everywhere, without comments and which would easily help the geologists from all regions of the globe to communicate".

He was also a paleontologist, part of the first team to excavate the archaeological site of Roc-en Paille (Chalonnes-sur-Loire, Maine-et-Loire). His very large collection of rocks, fossils and minerals is now visible at the Museum of Natural History in Angers.

A last honorable task kept Triger busy until the end of his life: the constitution of regular geological cross-sections of the whole eastern part of France. This huge work was carried out by a team of geologists directed by Triger: geological sections from Paris to Brest, from Le Mans to Angers, from Paris to Rennes, Vendôme to Brest...

On 16 December 1867 Triger died from a heart attack after a meeting at the Geological Society of France, where he served for 35 years.

Triger's name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

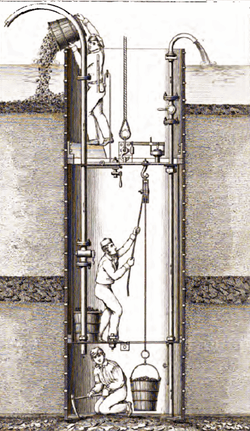

Details of the Triger Process

The work is done inside a chamber (known as a caisson) open at the bottom and in which compressed air is pumped to keep water out.[3][4] Originally developed for use in a coal mine (Mines de Chalonnes-sur-Loire, 1839), it was later applied to bridge construction and civil applications as well. The process was used for the Brooklyn Bridge (1870) in the United States and the Forth Bridge in Scotland among others. The health hazards of working in a hyperbaric environment were gradually discovered during these projects. The process was also used by Gustave Eiffel for the foundations of two of the four pillars supporting the Eiffel tower.

Nowadays the method is still used in tunneling and shaft sinking operations. Modern Tunnel Boring Machines use compressed air to excavate soils below water tables.

References

- ↑ sometimes mistakenly quoted as Jules Triger, who is his brother; Birth Certificate from the city of Mamers, Sarthe, France, 10 March 1801

- ↑ Notice sur la vie et les travaux de M. Triger, Société Géologique de France, Tome 25 des bulletins, 1868

- ↑ Davis, RH (1955). Deep Diving and Submarine Operations (6th ed.). Tolworth, Surbiton, Surrey: Siebe Gorman & Company Ltd. p. 693.

- ↑ Acott, C. (1999). "A brief history of diving and decompression illness.". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal. 29 (2). ISSN 0813-1988. OCLC 16986801. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

External links

- A. Banyai: A great invention with built-in hazards (1975)

- A french article on J. Triger written by François Martin, for Tunnel et Ouvrages Souterrains (2004).

- More information about his local contribution in Chalonnes-sur-Loire.