KeyBank

|

| |

| Public company | |

| Traded as |

NYSE: KEY S&P 500 Component |

| Industry | Financial services |

| Founded | 1825 Albany, New York |

| Headquarters | 127 Public Square, Cleveland, Ohio 44114[1] |

| Products | Banking |

| Revenue | $5.8 billion (2015)[2] |

| $892 million (2015)[3] | |

| Total assets | $135 billion (2016)[4] |

Number of employees | 20,000 (2016)[5] |

| Website |

www |

KeyBank, the primary business of its corporate parent KeyCorp, (NYSE: KEY) is an American regional bank headquartered in Cleveland, Ohio. Upon completing its purchase of First Niagara Bank in 2016, Key became the 18th largest US bank by total assets. Since 2008, KeyBank has been the only major bank based in Cleveland.

KeyCorp's primary regulator, under the Bank Holding Company Act, is the Federal Reserve, while KeyBank National Association is a nationally chartered bank, regulated by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Other subsidiaries are subject to regulation from Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, and other customary regulatory bodies.[6]

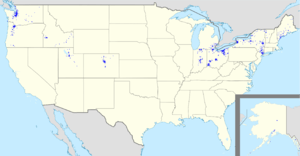

As of 2016, KeyBank had approximately 20,000 employees[7] and a diverse client base. Key's customer base spans retail, small business, corporate, and investment clients. There are 1,200 KeyBank[7] branches, located in Alaska, Colorado, Connecticut, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Utah, Vermont, and Washington, and 1,500 ATMs. KeyCorp maintains business offices in 31 states. As of 2015, Key was ranked 592 on the Fortune 500 list.[8]

History

KeyBank is the leading subsidiary of KeyCorp (NYSE: KEY), which was formed in 1994 through the merger of Society Corporation of Cleveland ("Society Bank") and KeyCorp ("Old KeyCorp") of Albany, New York. The merger would briefly make Key the 10th largest US bank. Its roots trace back to Commercial Bank of Albany, New York in 1825 and Cleveland's Society for Savings, founded in 1849.

Society Corporation (Society National Bank)

Society For Savings originated in 1849 as a mutual savings bank, founded by Samuel H. Mather. In 1867, the modest but growing bank would build Cleveland's first skyscraper, a 10-story building on Public Square. Despite erecting the tallest structure between New York and Chicago at the time, the bank remained extremely conservative. That aspect is highlighted by the fact that when it celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1949, it still only had one office although it had over $200 million in deposits. This conservatism helped the bank sidestep the numerous depressions and financial panics. In 1958, Society would convert from a mutual to a public company, which enabled it to grow quickly by acquiring 12 community banks between 1958 and 1978 under the banner Society National Bank. It would go through another growth spurt from 1979 to 1989, as it swallowed dozens of small banks and completed four mergers worth one billion dollars, most notably Cleveland-based Central National Bank in 1986. In 1987, Society CEO Gordon E. Heffern retired and was succeeded as Robert W. "Bob" Gillespie, who, although just 42, was a major figure and part of the office of the chairman for more than 5 years.[9] A year later, Gillespie would add the title of chairman. Gillespie started as a teller with Society to earn money while he was finishing his graduate studies.[10]

In the three years leading up to the KeyCorp merger, Society Corporation acquired Toledo-based Trustcorp in 1990 and Cleveland Trust, the major bank of holding company CleveTrust Corporation, in September 1991, a venerable Cleveland bank and Ohio's largest bank during the 1940s through the late 1970s. The Cleveland Trust deal put Society on the map as a large regional bank. The jewel of Cleveland Trust was its robust personal and corporate trust businesses. However, its footing became unsteady due to bad real estate loans, forcing the resignation of Cleveland Trust chairman Jerry V. Jarrett in 1990. Moreover, Gillespie was able to "one-up" Society's larger up-the-street archenemy, National City Bank, which also bid for Cleveland Trust.[11]

KeyBank

In 1825, New York Governor DeWitt Clinton signed a bill chartering the Commercial Bank of Albany. In 1865, Commercial Bank was reorganized under the National Banking Act of 1864, and changed its name to National Commercial Bank of Albany. Over a hundred years would pass before National Commercial would merge with First Trust and Deposit to become First Commercial Banks in 1971, still a modest New York State bank with 89 offices. Victor J. Riley, Jr., born 1931 in Buffalo, New York, became president and CEO in 1973. First Commercial would change its name to Key Bank Inc. in 1979.[12]

Riley embarked on a plan to grow Key through acquisitions. From the mid-1970s to early 1980s, it made numerous acquisitions throughout upstate New York. Beginning in the 1980s, Riley looked outside New York, expanding Key's footprint with an acquisition in Maine, and eventually adding branches in Massachusetts and Vermont. However, by the mid-1980s, the state banking regulators within New England began looking askance at New York-based banks controlling their capital. That, coupled with increasing competition for acquisition targets, caused Riley to essentially abandon the Northeast. Instead, he began searching for prey in the Pacific Northwest. Riley found a target-rich environment in rural and underserved areas. He snapped up small banks in Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, Washington and Oregon. He even went so far as to buy two banks in Alaska, for which he was flogged in the media and in banking circles. Unorthodox strategy aside, Riley quintupled Key's assets from $3 billion to $15 billion in just four years between 1985 and 1990.

While the early 1990s recession rocked many banks, Key had ample capital. In fact, it would buy the assets of two failed thrifts from the government: Empire Federal Savings and Loan and Goldome Savings Bank along with M&T Bank and others . Once the recession passed, Key returned to the hunt, mostly tuck-in deals within its existing footprint. For instance, in March 1992, it bought Tacoma-based Puget Sound Bancorp for $807.2 million to bolster its presence in Washington.[13] Also in 1992, Key acquired Home Federal Savings of Fort Collins, its first move into Colorado. Key soon amassed nearly 700 banking offices.[14]

By 1993, the rural strategy with local management and minimal technology made Key a very profitable bank. However, it was getting tougher for Riley and CFO William Dougherty to maintain their 15 percent return on equity target and investors were cooling on Key stock after many high growth years. Accordingly, Key began testing a Vision 2001 computer system, which would speed up and enhance the loan process through faster credit scoring, loan servicing and collection capabilities.

Transformational merger

Although Gillespie had built Society into a regional powerhouse in the Midwest, he wanted to vault the bank into the big leagues. He concluded Key, a bank with similar ambitions, was a suitable partner. Society and Key held talks in 1990 at Gillespie's prompting, but Riley decided to stay the course of smaller, more lucrative acquisitions with obvious synergies. Yet, news reports swirled that a possible merger was in the works in the fall of 1993. Key was the 29th largest U.S. bank with $26 billion in assets, while Society was the 25th largest with $32 billion in assets.[15] Both needed a merger to improve their prospects. For its part, Key needed a succession plan due to the lack of an obvious successor to the 62-year-old Riley. In one week in June 1993, the bench had become barren - Chief Banking Officer James Waterston, hired the year before, quit and publicly stated that he was frustrated with the pace of achieving his goal of running a large bank. The head of KeyBank of Washington, Hans Harjo, was pushed out over an apparent dispute to move its headquarters from Seattle to Tacoma.[16] It also became clear that Key would have to undertake a technology infrastructure upgrade to connect its far-flung offices. Meanwhile, Society was in search of higher growth and longed to expand its presence outside of the so-called rust belt states of Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana.

The merger was announced in early October 1993. This time it was Riley who made the first move. Riley, recuperating at his Albany home after breaking his hip in a horse-riding accident in Wyoming, called Gillespie directly. The two quickly sketched out the deal. The banks were roughly the same size in assets and had very little geographic overlap, so it was touted as an out-of-market merger in which few branches would need to be sold off. It would create a $58 billion banking behemoth with a footprint that literally stretched from Portland, Maine to Portland, Oregon. Furthermore, the deal would plug many of the perceived holes for both partners.[17] The soft-spoken Gillespie was just 49 and Society had cultivated a deep bench of lieutenants. More importantly, Society had the computer systems and technology expertise to combine the two banks, along with capable tech boss Allen J. Gula.[18] Riley also lamented the modest Albany International Airport, which lost service from several major airlines in the 1980s and complicated air travel for Key executives. Ohio also had lower state taxes than New York. Lastly, Society had recently built a 947-foot headquarters tower that was more commensurate with a major bank than the modest buildings used in Albany. These issues made Cleveland the preferable location for the new headquarters. Conversely, Key's brand was more recognizable.

The deal was structured as a merger of equals. While the merged bank took the KeyCorp name, Society was the nominal survivor; KeyCorp retains Society's pre-1994 stock price history. As per the agreement, the merged bank was headquartered in Cleveland. The Society Bank name continued to be used in the former Society Corporation footprint for an additional two more years before it was retired in June 1996 and all Society Bank branches wore the KeyBank name. This change was made so that Society Bank and KeyBank customers could bank at any KeyCorp facility nationwide. It also surrendered its separate charters in favor of a single national charter, eliminating the costs of holding separate bank charters in each state.

Riley would become chairman and CEO of the new KeyCorp and Gillespie would be president and chief operating officer. Despite assurances from both Riley and Gillespie, the city of Albany and then-Governor Mario Cuomo openly fretted that the merger would be bad for the state capital since Key and its subsidiaries owned or leased more than 10 percent of Albany's commercial office space.[19] As of 2014, only about 225 non-branch employees are still based in Albany at the KeyCorp Tower.[20]

Society and Key completed the merger on March 1, 1994 after regulatory approval. From the outset, the integration would be daunting and promised little expense reduction given the complexities and few synergies. Wall Street analysts were puzzled.[17] Although it was touted as a merger of equals, Key and Society were an odd couple. Key was a decentralized community bank comprising two banking networks—an eastern network in New England and upstate New York and a western one in the Rockies and Pacific Northwest—within a single corporate structure. Society was a classic big-city commercial bank with a centralized structure largely concentrated in three states.

Riley planned to retire as CEO at the end of 1995.[21] He decided to accelerate it by 4 months, however, instead stepping down on September 1, 1995. Gillespie took the helm as CEO and later chairman, allowing his protege Henry Meyer to become COO and later president.

Further transformation

While still integrating Society and Key, Gillespie attempted to turn Key into a financial services powerhouse. Between 1995 and 2001, Gillespie initiated 9 significant acquisitions and 6 divestitures.[22]

In late 1998, Key bought hometown regional brokerage firm, McDonald & Co. for $580 million in an all-stock transaction.[23] The McDonald acquisition was the largest non-banking deal in both size and impact on Key. McDonald was eventually sold to the U.S. investment arm of Swiss banking giant UBS AG in 2007 for roughly $280 million.[24] As a result, Key began processing all subsequent securities transactions under its new broker-dealer name, "KeyBanc Capital Markets Inc", in April 2007.[25]

However, investors were becoming wary of all the Gillespie-era deals. In fact, some believed that Gillespie was making all the moves to cover up poor performance, although in hindsight that appears to be far from truth. The concept was dubbed "burning the furniture," implying that Key would sell an asset to obfuscate earnings. For instance, Key sold its residential mortgage servicing to Countrywide Financial in 1995, shareholder services in 1996, various chunks of the bank in 1997-1999 (i.e. Wyoming, Florida, and Long Island), and credit card operations to The Associates in 2000 (which would quickly thereafter be swallowed by Citigroup).

But Gillespie was attempting to increase fee-income by acquiring high-growth businesses (like McDonald and equipment financing firm Leastec) and decreasing the exposure to the bank's shrinking population base in its primary footprint, so-called rust belt states such as Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana. Gillespie stepped down as CEO on February 1, 2001, and then as chairman at the annual meeting on May 17. That would usher in the Henry Meyer era.

2002 through present

In October 2008, Key received approximately $2.5 billion in TARP funds, which its Chairman stated would be used in part to grow even larger.[26] Key was one of the last major banks to pay back TARP funds.[27]

In May 2011, Key made history by naming Beth E. Mooney, previously the bank's president, as the first female Chairman and CEO of a top 20 bank.[27]

In January 2012, Key acquired 37 former HSBC branches in Upstate New York from First Niagara for $110 million.[28]

In January 2015, KeyBank NA participated in the construction debt financing syndicate behind the Balko Wind Project purchased from Apex Clean Energy by D.E. Shaw Renewable Investments[29]

On October 30, 2015, KeyCorp and First Niagara Financial Group announced that they have entered into a definitive agreement under which KeyCorp will acquire First Niagara in a cash and stock transaction for total consideration valued at approximately $4.1 billion.[30] The deal will strengthen Key's position in Upstate New York and New England, as well as entering Pennsylvania for the first time with a presence in both Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. In Pittsburgh, Key will be a top five bank, and will acquire branches that were once part of crosstown rival National City Corp., which Key had tried to acquire from PNC Financial Services following PNC's takeover of National City in 2008 before being outbid by First Niagara.[31][32] On April 28, 2016, KeyCorp announced that 18 First Niagara branches in Erie and Niagara Counties in New York will be sold to Northwest Savings Bank for antitrust reasons.[33]

Naming Rights

KeyCorp holds the naming rights to KeyBank Center in Buffalo, New York. Key acquired the naming rights after as part of their purchase of First Niagara. The arena is home to the Buffalo Sabres of the National Hockey League. The First Niagara purchase also gained Key the rights to KeyBank Pavilion near Pittsburgh.

The company no longer owns the naming rights to KeyArena in Seattle, Washington,[34] although the building continues to use the name. On April 11, 1995, the city of Seattle sold the naming rights to KeyCorp for $15.1 million, which renamed the Coliseum as KeyArena. In March 2009, the city and KeyCorp signed a new deal for a two-year term that ended December 31, 2010, at an annual fee of $300,000.[35] The company did not renew the naming rights.[34]

Controversy

According to The Huffington Post, KeyBank is "one of many private institutions without a clear policy about cancelling the student loan debt of a deceased individual."[36] KeyBank attracted criticism over the student loan of Christopher Bryski, a Rutgers University undergraduate who died from a traumatic brain injury in 2006. Christopher owed KeyBank roughly $50,000 at the time of his death, and KeyBank demanded his parents, the cosigners of his debt, continue making the payments after he died.[36] Christopher's brother Ryan launched a petition which was signed by over 78,000 people in its first week, asking KeyBank to forgive the debt.[36] KeyBank agreed to forgive the debt several days later.[36]

References

- ↑ "Facts About KeyBank".

- ↑ https://www.key.com/about/company-information/key-company-overview.jsp

- ↑ http://investor.key.com/file/Index?KeyFile=32607595

- ↑ https://www.key.com/about/company-information/key-company-overview.jsp

- ↑ https://www.key.com/about/company-information/key-company-overview.jsp

- ↑ "KeyCorp 2013 Annual Report, Form 10K, page 7" (PDF). Key Bank. Retrieved 2014-12-04.

- 1 2 "Key Facts and Figures publisher=Key Bank". Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- ↑ "Fortune 500 2014". Fortune. Retrieved 2015-12-14.

- ↑ "Society Corporation". Answers.com. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ Roger Pusey (5 October 1993). "Merger Won't Change Key Bank". Deseret news. deseretnews.com. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ Michael Quint (21 May 1991). "National City Makes Bid for Cleveland Trust". The New York Times. NYTimes.com. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ "KeyCorp". Funding Universe. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ "MERGER KeyCorp to buy Puget Sound Bancorp". Kitsap Sun. Kitsapsun.com. 9 March 1992. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ "Company News". The New York Times. NYTimes.com. 23 October 1992. Retrieved October 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Saul Hansell (2 October 1993). "A Keycorp-Society Merger Is Expected to Be Disclosed". The New York Times. NYTimes.com. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ Himanee Gupta (24 June 1993). "Successor To Key Bank Chairman Is Picked". The Seattle Times. seattletimes.com. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- 1 2 Saul Hansell (5 October 2003). "Keycorp-Society Deal Is Merger of Equals". The New York Times. NYTimes.com. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ "Schedule 14A". EDGAR online. 18 April 1994. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ "Albany Officials Gloomy Over Bank Company's Merger and Move". The New York Times. NYTimes.com. 10 October 1993. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ "A new push to fill downtown Albany's biggest office buildings". Albany Business Review. 23 July 2014. Retrieved 2014-12-04.

- ↑ Roger Pusey (18 May 1995). "KeyCorp aims to become 'First Choice' in finance". Deseret News. Google news.com. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ Shawn A. Turner (23 October 2006). "Key poised to resume bank acquisitions". Crain's Cleveland Business. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- ↑ "McDonald and Co. Securities". Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. 18 April 2004. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ John Churchill (6 September 2006). "UBS Buys Another Brokerage". Registered Rep. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ "KeyBanc Capital Markets Inc. Customer". KeyBanc. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ Roger Mezger (27 October 2008). "KeyCorp plans to use bailout money to be a buyer". Cleveland Plain Dealer. Cleveland.com. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- 1 2 From Secretary To CEO: Beth Mooney Makes Banking History Forbes.com, September 6, 2011. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- ↑ "Key Bank Buys HSBC Branches from First Niagara". WBEN (AM). WBEN.com. 12 January 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ↑ "D. E. Shaw Renewable Investments Acquires 300-MW Balko Wind from Apex Clean Energy". MarketWatch.

- ↑ https://www.key.com/about/articles/keybank-first-niagara-agreement-103015.jsp?ppc=Q4_prFN_tw

- ↑ Patricia Sabatini (21 March 2009). "FNB won't buy National City units". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. post-gazette.com. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ http://triblive.com/business/headlines/9351520-74/niagara-keycorp-based#axzz3r6GNxg00

- ↑ http://strictlybusiness.buffalonews.com/2016/04/28/keycorp-names-18-first-niagara-branches-agreed-sell/

- 1 2 "KeyArena no more?". Puget Sound Business Journal. Retrieved 2014-12-04.

- ↑ "Ordinance 122944". City of Seattle. 30 March 2009. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- 1 2 3 4 Berlin, Loren (25 April 2012). "Christopher Bryski, Rutgers Student, Died But His Student Loan Lives On". The Huffington Post. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to KeyBank. |

-

- Business data for KeyBank: Google Finance

- Yahoo! Finance

- Reuters

- SEC filings

- Key Education Resources

- Key Equipment Finance

- Key Marine Financing - Boat loans

- Top 50 Bank Holding Companies By Assets