Lake Tanganyika

| Lake Tanganyika | |

|---|---|

Lake Tanganyika from space, June 1985 | |

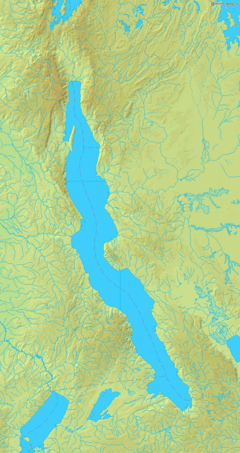

map | |

| Coordinates | 6°30′S 29°50′E / 6.500°S 29.833°ECoordinates: 6°30′S 29°50′E / 6.500°S 29.833°E |

| Lake type | Rift Valley Lake |

| Primary inflows |

Ruzizi River Malagarasi River Kalambo River |

| Primary outflows | Lukuga River |

| Catchment area | 231,000 km2 (89,000 sq mi) |

| Basin countries |

Burundi DR Congo Tanzania Zambia |

| Max. length | 673 km (418 mi) |

| Max. width | 72 km (45 mi) |

| Surface area | 32,900 km2 (12,700 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 570 m (1,870 ft) |

| Max. depth | 1,470 m (4,820 ft) |

| Water volume | 18,900 km3 (4,500 cu mi) |

| Residence time | 5500 years[1] |

| Shore length1 | 1,828 km (1,136 mi) |

| Surface elevation | 773 m (2,536 ft)[2] |

| Settlements |

Kigoma, Tanzania Kalemie, DRC Bujumbura, Burundi |

| References | [2] |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

Lake Tanganyika is an African Great Lake. It is estimated to be the second largest freshwater lake in the world by volume, and the second deepest, in both cases, after only Lake Baikal in Siberia;[3] it is also the world's longest freshwater lake. The lake is divided among four countries – Tanzania, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Burundi, and Zambia, with Tanzania (46%) and DRC (40%) possessing the majority of the lake. The water flows into the Congo River system and ultimately into the Atlantic Ocean.

The name apparently refers to "Tanganika, 'the great lake spreading out like a plain', or 'plain-like lake'."[4]:Vol.Two,16

Geography

Lake Tanganyika is situated within the Albertine Rift, the western branch of the East African Rift, and is confined by the mountainous walls of the valley. It is the largest rift lake in Africa and the second largest lake by volume in the world. It is the deepest lake in Africa and holds the greatest volume of fresh water, accounting for 18% of the world's available fresh water. It extends for 676 km (420 mi) in a general north-south direction and averages 50 km (31 mi) in width. The lake covers 32,900 km2 (12,700 sq mi), with a shoreline of 1,828 km (1,136 mi), a mean depth of 570 m (1,870 ft) and a maximum depth of 1,470 m (4,820 ft) (in the northern basin). It holds an estimated 18,900 cubic kilometres (4,500 cu mi).[5] This is equivalent to about 16% of all fresh water on Earth. It has an average surface temperature of 25 °C (77 °F) and a pH averaging 8.4.

The enormous depth and tropical location of the lake can prevent 'turnover' of water masses, which means that much of the lower depths of the lake are so-called 'fossil water' and are anoxic (lacking oxygen). The catchment area of the lake is 231,000 km2 (89,000 sq mi). Two main rivers flow into the lake, as well as numerous smaller rivers and streams (whose lengths are limited by the steep mountains around the lake). There is one major outflow, the Lukuga River, which empties into the Congo River drainage.

The major river flowing into the lake is the Ruzizi River, formed about 10,000 years ago, which enters the north of the lake from Lake Kivu. The Malagarasi River, which is Tanzania's second largest river, enters the east side of Lake Tanganyika. The Malagarasi is older than Lake Tanganyika and, before the lake was formed, directly drained into the Congo River.

The lake has a complex history of changing flow patterns, due to its high altitude, great depth, slow rate of refill and mountainous location in a turbulently volcanic area that has undergone climate changes. Apparently it has rarely in the past had an outflow to the sea. It has been described as 'practically endorheic' for this reason. The lake's connection to the sea is dependent on a high water level allowing water to overflow out of the lake through the Lukunga into the Congo.

Due to the lake's tropical location, it suffers a high rate of evaporation. Thus it depends on a high inflow through the Ruzizi out of Lake Kivu to keep the lake high enough to overflow. This outflow is apparently not more than 12,000 years old, and resulted from lava flows blocking and diverting the Kivu basin's previous outflow into Lake Edward and then the Nile system, and diverting it to Lake Tanganyika. Signs of ancient shorelines indicate that at times Tanganyika may have been up to 300 m lower than its present surface level, with no outlet to the sea. Even its current outlet is intermittent and may not have been operating when first visited by Western explorers in 1858.

The lake may also have at times had different inflows and outflows: inward flows from a higher Lake Rukwa, access to Lake Malawi and an exit route to the Nile have all been proposed to have existed at some point in the lake's history.[6]

Islands

There are several islands in Lake Tanganyika. The most important of them are

- Kavala Island (The Democratic Republic of the Congo)

- Mamba-Kayenda Islands (The Democratic Republic of the Congo)

- Milima Island (The Democratic Republic of the Congo)

- Kibishie Island (The Democratic Republic of the Congo)

- Mutonowe Island ( Zambia)

- Kumbula Island ( Zambia)

Biology

Fish

The lake holds at least 250 species of cichlid fish and 75 species of non-cichlid fish,[7] most of which live along the shoreline down to a depth of approximately 180 metres (590 ft). The largest biomass of fish, however, is in the pelagic zone (open waters) and is dominated by six species: two species of "Tanganyika sardine" and four species of predatory Lates (related to, but not the same as, the Nile perch that has devastated Lake Victoria cichlids). Lake Tanganyika is considered the oldest of the East African lakes, and has the most morphologically and genetically diverse groups of cichlids. This lake also has the largest number of endemic cichlid genera of all African lakes.[8] Almost all (98%) of the Tanganyikan cichlid species are endemic to the lake, and Lake Tanganyika is thus an important biological resource for the study of speciation in evolution.[3][9] Among the non-cichlid fish, 59% of the species are endemic.[7] Lake Tanganyika is the most diverse extent of adaptive radiation.[8]

Many species of cichlids from Lake Tanganyika, such as fish from the brightly coloured Tropheus genus, are popular fish among aquarium owners due to their bright colors. Recreating a Lake Tanganyika biotope[10] to host those cichlids in a habitat similar to their natural environment is also popular in the aquarium hobby.

Invertebrates

Lake Tanganyika is home to a large number of invertebrates, including many endemics:

- Molluscs and crustaceans

A total of 68 freshwater snail species (45 endemic) and 15 bivalve species (8 endemic) are known from the lake.[11] Many of the snails are unusual for species living in freshwater in having noticeably thickened shells and/or distinct sculpture, features more commonly seen in marine snails. They are referred to as thallasoids, which can be translated to "marine-like".[12] All the Tanganyika thallasoids, which are part of Prosobranchia, are endemic to the lake.[12] Initially they were believed to be related to similar marine snails, but they are now known to be unrelated. Their appearance is now believed to be the result of the highly diverse habitats in Lake Tanganyika and evolutionary pressure from snail-eating fish and, in particular, Platythelphusa crabs.[7][12][13] A total of 17 freshwater snail genera are endemic to the lake, such as Lavigeria, Reymondia, Spekia, Tanganyicia and Tiphobia.[12] There are about 30 species of non-thallasoid snails in the lake, but only five of these are endemic, including Ferrissia tanganyicensis and Neothauma tanganyicense.[12] The latter is the largest Tanganyika snail and its shell is often used by small shell-dwelling cichlids.[14]

Crustaceans are also highly diverse in Tanganyika with more than 200 species, of which more than half are endemic.[7] They include 10 species of freshwater crabs (9 Platythelphusa and Potamonautes platynotus; all endemic), at least 11 species of small atyid shrimp (Atyella, Caridella and Limnocaridina), a palaemonid shrimp (Macrobrachium moorei), and several copepods.[15][16]

Among Rift Valley lakes, Lake Tanganyika far surpasses all others in terms of crustacean and freshwater snail richness (both in total number of species and number of endemics).[11] For example, the only other Rift Valley lake with endemic freshwater crabs is Lake Kivu with two species.[17]

- Other invertebrates

The diversity of other invertebrate groups in Lake Tanganyika is often not well-known, but there are at least 20 described species of leeches (12 endemics),[18] 9 sponges (7 endemic), 6 bryozoa (2 endemic), 11 flatworms (7 endemic), 20 nematodes (7 endemic), 28 annelids (17 endemic)[7] and the small hydrozoan jellyfish Limnocnida tanganyicae.[19]

Industry

It is estimated that 25–40% of the protein in the diet of the approximately one million people living around the lake comes from lake fish.[20] Currently, there are around 100,000 people directly involved in the fisheries operating from almost 800 sites. The lake is also vital to the estimated 10 million people living in the greater basin.

Lake Tanganyika fish can be found exported throughout East Africa. Commercial fishing began in the mid-1950s and has had an extremely heavy impact on the pelagic fish species; in 1995 the total catch was around 180,000 tonnes. Former industrial fisheries, which boomed in the 1980s, have subsequently collapsed.

Transport

Two ferries carry passengers and cargo along the eastern shore of the lake: MV Liemba between Kigoma and Mpulungu and MV Mwongozo between Kigoma and Bujumbura.

- The port town of Kigoma is the railhead for the railway from Dar es Salaam in Tanzania.

- The port town of Kalemie (previously named Albertville) is the railhead for the D.R. Congo rail network.

- The port town of Mpulungu is a proposed railhead for Zambia.[21]

On Dec. 12, 2014, the ferry MV Mutambala capsized on Lake Tanganyika, and more than 120 lives were lost.[22]

History

It is thought that early Homo Sapiens was making an impact on the region already during the stone age. The time period of the Middle Stone Age to Late Stone Age is described as an age of advanced hunter-gatherers. It is believed they would have caused megafaunal extinctions.[23]

There are many methods in which the native people of the area were fishing. Most of them included using a lantern as a lure for fish that are attracted to light. There were three basic forms. One called Lusenga which is a wide net used by one person from a canoe. The second one is using a lift net. This was done by dropping a net deep below the boat using two parallel canoes and then simultaneously pulling it up. The third is called Chiromila which consisted of three canoes. One canoe was stationary with a lantern while another canoe holds one end of the net and the other circles the stationary one to meet up with the net. [24]

The first known Westerners to find the lake were the British explorers Richard Burton and John Speke, in 1858. They located it while searching for the source of the Nile River. Speke continued and found the actual source, Lake Victoria. Later David Livingstone passed by the lake. He noted the name "Liemba" for its southern part, a word probably from the Fipa language, and in 1927 this was chosen as the new name for the conquered German First World War ship Graf von Götzen which is still serving the lake up to the present time.[25]

World War I

The lake was the scene of two celebrated battles during World War I.

With the aid of the Graf Goetzen (named after Count Gustav Adolf Graf von Götzen, the former governor of German East Africa), the Germans had complete control of the lake in the early stages of the war. The ship was used both to ferry cargo and personnel across the lake, and as a base from which to launch surprise attacks on Allied troops.[26]

It therefore became essential for the Allied forces to gain control of the lake themselves. Under the command of Lieutenant Commander Geoffrey Spicer-Simson the British Royal Navy achieved the monumental task of bringing two armed motor boats HMS Mimi and HMS Toutou from England to the lake by rail, road and river to Albertville (since renamed Kalemie in 1971) on the western shore of Lake Tanganyika. The two boats waited until December 1915, and mounted a surprise attack on the Germans, with the capture of the gunboat Kingani. Another German vessel, the Hedwig, was sunk in February 1916, leaving the Götzen as the only German vessel remaining to control the lake.[26]

As a result of their strengthened position on the lake, the Allies started advancing towards Kigoma by land, and the Belgians established an airbase on the western shore at Albertville. It was from there, in June 1916, that they launched a bombing raid on German positions in and around Kigoma. It is unclear whether or not the Götzen was hit (the Belgians claimed to have hit it but the Germans denied this), but German morale suffered and the ship was subsequently stripped of its gun since it was needed elsewhere.[26]

The war on the lake had reached a stalemate by this stage, with both sides refusing to mount attacks. However, the war on land was progressing, largely to the advantage of the Allies, who cut off the railway link in July 1916 and threatened to isolate Kigoma completely. This led the German commander, Gustav Zimmer, to abandon the town and head south. In order to avoid his prize ship falling into Allied hands, Zimmer scuttled the vessel on July 26, 1916. The vessel was later raised in 1924 and renamed MV Liemba (see transport).[26]

Che Guevara

In 1965 Argentinian revolutionary Che Guevara used the western shores of Lake Tanganyika as a training camp for guerrilla forces in the Congo. From his camp, Che and his forces attempted to overthrow the government, but ended up pulling out in less than a year since the National Security Agency (NSA) had been monitoring him the entire time and aided government forces in ambushing his guerrillas.

Recent history

In 1992 Lake Tanganyika featured in the British TV documentary series Pole to Pole. The BBC documentarian Michael Palin stayed on board the MV Liemba and travelled across the lake.

Since 2004 the lake has been the focus of a massive Water and Nature Initiative by the IUCN. The project is scheduled to take five years at a total cost of US$27 million. The initiative is attempting to monitor the resources and state of the lake, set common criteria for acceptable level of sediments, pollution, and water quality in general, and design and establish a lake basin management authority.

Effects of global warming

Because of increasing global temperature there is a direct correlation to lower productivity in Lake Tanganyika [27] Southern winds create upwells of deep nutrient-rich water on the southern end of the lake. This happens during the cooler months (May to September). These nutrients that are in deep water are vital in maintaining the aquatic food web. The southernly winds are slowing down which limits the ability for the mixing of nutrients. This is correlating with less productivity in the lake.

See also

References

- ↑ Yohannes, Okbazghi (2008). Water resources and inter-riparian relations in the Nile basin. SUNY Press. p. 127.

- 1 2 "LAKE TANGANYIKA". www.ilec.or.jp. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- 1 2 "~ZAMBIA~". www.zambiatourism.com. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ↑ Stanley, H.M., 1899, Through the Dark Continent, London: G. Newnes, Vol. One ISBN 0486256677, Vol. Two ISBN 0486256685

- ↑ "Datbase Summary: Lake Tanganyika". www.ilec.or.jp. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ↑ Lévêqu, Christian (1997). Biodiversity Dynamics and Conservation: The Freshwater Fish of Tropical Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 110.

- 1 2 3 4 5 West, K. (prepared by) (2001). Lake Tanganyika: Results and Experiences of the UNDP/GEF Conservation Initiative (RAF/92/G32) in Burundi, D.R. Congo, Tanzania, and Zambia. Lake Tanganyika Biodiversity Project.

- 1 2 Meyer, Matchiner, Salburger, Britta, Michael, Walter (25 November 2013). "A tribal level phylogeny of Lake Tanganyika cichlid fishes based on a genomic multi-marker approach". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution.

- ↑ Kornfield, Ivy & Smith, Peter A. African Cichlid Fishes: Model Systems for Evolutionary Biology, Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, Vol. 31: 163-196, Nov. 2000

- ↑ "tanganyika biotope aquarium". Aquariums Life. 2010-02-10. Retrieved 2014-02-03.

- 1 2 Segers, H.; and Martens, K; editors (2005). The Diversity of Aquatic Ecosystems. p. 46. Developments in Hydrobiology. Aquatic Biodiversity. ISBN 1-4020-3745-7

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brown, D. (1994). Freshwater Snails Of Africa And Their Medical Importance. 2nd edition. ISBN 0-7484-0026-5

- ↑ West, K.; and Cohen, A. (1996). Shell microstructure of gastropods from Lake Tanganyika, Africa: adaptation, convergent evolution, and escalation. Evolution 50: 672–682.

- ↑ Koblmüller; Duftner; Sefc; Aibara; Stipacek; Blanc; Egger; and Sturmbauer (2007). Reticulate phylogeny of gastropod-shell-breeding cichlids from Lake Tanganyika — the result of repeated introgressive hybridization. BMC Evolutionary Biology 7: 7.

- ↑ Marijnissen; Michel; Daniels; Erpenbeck; Menken; Schram (2006). Molecular evidence for recent divergence of Lake Tanganyika endemic crabs (Decapoda: Platythelphusidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 40(2): 628–634.

- ↑ Fryer, G. (2006). Evolution in ancient lakes: radiation of Tanganyikan atyid prawns and speciation of pelagic cichlid fishes in Lake Malawi. Hydrobiologia 568(1): 131–142.

- ↑ Cumberlidge, N.; and Meyer, K. S. (2011). A revision of the freshwater crabs of Lake Kivu, East Africa. Journal Articles. Paper 30.

- ↑ Segers, H.; and Martens, K; editors (2005). The Diversity of Aquatic Ecosystems. p. 44. Developments in Hydrobiology. Aquatic Biodiversity. ISBN 1-4020-3745-7

- ↑ Salonen; Högmander; Langenberg; Mölsä; Sarvala; Tarvainen; and Tiirola (2012). Limnocnida tanganyicae medusae (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa): a semiautonomous microcosm in the food web of Lake Tanganyika. Hydrobiologia 690(1): 97-112.

- ↑ "Global warming is killing off tropical lake fish - Study of Lake Tanganyika". www.mongabay.com. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ↑ "Railways Africa - Extending beyond Chipata". railwaysafrica.com. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ↑ "DR Congo: Many dead after ferry sinks on Lake Tanganyika". BBC News. 2014-12-14. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

- ↑ East African Ecosystems and Their Conservation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Lake Tanganyika and Its Life. Oxford Press. 1991.

- ↑ The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa from 1865 ..., Volume 1 p. 338; via google books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2014-02-03.

- 1 2 3 4 Giles Foden: Mimi and Toutou Go Forth — The Bizarre Battle for Lake Tanganyika, Penguin, 2004.

- ↑ O'Reilly, Catherine M.; Alin, Simone R.; Plisnier, Pierre-Denis; Cohen, Andrew S.; Mckee, Brent A. (August 14, 2003). "Climate change decreases aquatic ecosystem productivity of Lake Tanganyika, Africa". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature01833. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lake Tanganyika. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lake Tanganyika. |

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- Index of Lake Tanganyika Cichlids

-

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Tanganyika". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- "Tanganyika". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- "Tanganyika". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.