Lucius of Britain

| Saint Lucius of Britain | |

|---|---|

|

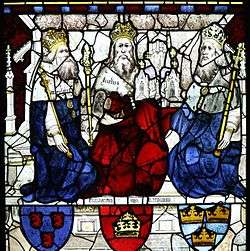

King Lucius (middle) from the East Window in York Minster | |

| Died | 2nd century |

| Venerated in |

Roman Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | Cathedral of Chur |

| Feast | 3 December |

| Patronage | Liechtenstein; Diocese of Vaduz; Diocese of Chur |

Lucius is a legendary 2nd-century King of the Britons and saint traditionally credited with introducing Christianity into Britain. Lucius is first mentioned in a 6th-century version of the Liber Pontificalis, which says that he sent a letter to Pope Eleutherius asking to be made a Christian. The story became widespread after it was repeated in the 8th century by Bede, who added the detail that after Eleutherius granted Lucius' request, the Britons followed their king in conversion and maintained the Christian faith until the Diocletianic Persecution of 303. Later writers expanded the legend, giving accounts of missionary activity under Lucius and attributing to him the foundation of certain churches.[1]

There is no contemporary evidence for a king of this name, and modern scholars believe that his appearance in the Liber Pontificalis is the result of a scribal error.[1] However, for centuries the story of this "first Christian king" was widely believed, especially in Britain, where it was considered an accurate account of Christianity among the early Britons. During the English Reformation, the Lucius story was used in polemics by both Catholics and Protestants; Catholics considered it evidence of papal supremacy from a very early date, while Protestants used it to bolster claims of the primacy of a British national church founded by the crown.[2]

Sources

The first mention of Lucius and his letter to Eleutherius is in the Catalogus Felicianus, a version of the Liber Pontificalis created in the 6th century.[1] Why the story appears there has been a matter of debate. In 1868 Arthur West Haddan and William Stubbs suggested that it might have been pious fiction invented to support the efforts of missionaries in Britain in the time of Saint Patrick and Palladius.[3] In 1904 Adolf von Harnack proposed that there had been a scribal error in Liber Pontificalis with ‘Britanio' Britannia being written as an erroneous expansion for 'Britio' Birtha or Britium in what is now Turkey. In 'King Lucius of Britain' [4] Knight reveals several problems with Harnack’s theory, namely that Abgar was King of Edessa, not ‘Britio’, which was the local name for a castle within his realm, and he is never called Lucius of Britio/Birtha in contemporary sources, only Abgar of Edessa. As Abgar was noted as an existing Christian ruler, Knight suggests there is no reason for him to have written to the Pope requesting baptism. Thus the similarities that Harnack noted between Lucius of Britain and (Lucius) Agbar Lucius Aelius Megas Abgar IX.[3] of Edessa, who built a Birta, are not substantial enough, argues Knight, to justify Harnack’s proposed identification, nor the sway it holds in modern scholarship.

The English monk Bede included the Lucius story in his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, completed in 731. He may have heard it from a contemporary who had been to Rome, such as Nothhelm.[1] Bede adds the detail that Lucius' new faith was thereafter adopted by his people, who maintained it until the Diocletianic Persecution. Following Bede, versions of the Lucius story appeared in the 9th-century Historia Brittonum, and in 12th-century works such as Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, William of Malmesbury's Gesta pontificum Anglorum, and the Book of Llandaff.[1][5] The most influential of these accounts was Geoffrey's, which emphasizes Lucius' virtues and gives a detailed, if fanciful, account of the spread of Christianity during his reign.[6] In his version, Lucius is the son of the benevolent King Coilus and rules in the manner of his father.[7] Hearing of the miracles and good works performed by Christian disciples, he writes to Pope Eleutherius asking for assistance in his conversion. Eleutherius sends two missionaries, Fuganus and Duvianus, who baptise the king and establish a successful Christian order throughout Britain. They convert the commoners and flamens, turn pagan temples into churches, and establish dioceses and archdioceses where the flamens had previously held power.[7] The pope is pleased with their accomplishments, and Fuganus and Duvianus recruit another wave of missionaries to aid the cause.[8] Lucius responds by granting land and privileges to the Church. He dies without heir in AD 156, thereby weakening Roman influence in Britain.[9]

Later traditions are mostly based on one of these accounts, probably including a medieval inscription at the church of St Peter-upon-Cornhill in Cornhill, London in the City of London. There, he is credited with having founded the church in AD 179.

Saint Lucius's feast day is on 3 December and he was canonized through the pre-congregational method.

Veneration in Chur

The legendary first bishop of Chur and patron saint of the Grisons (Switzerland) was also named Lucius, with whom the British Lucius is not to be confused. It is possible, however, that the mentioning of Saint Lucius of Britain in the Liber Pontificalis soon led to a scholarly identification of the otherwise somewhat shapeless patron saint with his more prominent British namesake. His supposed relics are still kept in the cathedral of Chur, although there is little doubt among scholars that the bishopric was only established some 150 years after its alleged founder was martyred.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Smith, Alan (1979). "Lucius of Britain: Alleged King and Church Founder". Folklore. 90 (1): 29–36. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1979.9716121.

- ↑ Heal, Felicity (2005). "What can King Lucius do for you? The Reformation and the Early British Church". The English Historical Review. 120 (487): 593–614. doi:10.1093/ehr/cei122.

- 1 2 Heal, p. 614.

- ↑ 'King Lucius of Britain' by David J. Knight (ISBN 9780752445724)

- ↑ Heal, p. 595.

- ↑ Heal, p. 594.

- 1 2 Historia Regum Britanniae, Book 4, ch. 19.

- ↑ Historia Regum Britanniae, Book 4, ch. 20.

- ↑ Historia Regum Britanniae, Book 5, ch. 1.

References

- Heal, Felicity (2005). "What can King Lucius do for you? The Reformation and the Early British Church". The English Historical Review. 120 (487): 593–614. doi:10.1093/ehr/cei122.

- Smith, Alan (1979). "Lucius of Britain: Alleged King and Church Founder". Folklore. 90 (1): 29–36. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1979.9716121.

External links

- Alan Smith, 'Lucius of Britain: Alleged King and Church Founder', Folklore, Vol. 90, No. 1 (1979), pp. 29–36

- Homer Nearing, Jr., Local Caesar Traditions in Britain, Speculum, Vol. 24, No. 2 (April 1949), pp. 218–227

- Saint Lucius engraved by Leonhard Beck from the De Verda collection

| Legendary titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Coilus |

King of Britain | Vacant Interregnum Title next held by Geta |