Lusitanians

The Lusitanians (or Latin: Lusitani) were an Indo-European people living in the west of the Iberian Peninsula prior to its conquest by the Roman Republic and the subsequent incorporation of the territory into the Roman province of Lusitania (most of modern Portugal, Extremadura and a small part of the province of Salamanca).

Origins

Classical sources mention Lusitanian leader Viriathus as the leader of the Celtiberians, in their war against the Romans.[1] The Greco-Roman historian Diodorus Siculus attributed them a name of a Germanic tribe: "Those who are called Lusitanians are the bravest of all Cimbri".[2] The Lusitanians were also called Belitanians, according to the diviner Artemidorus.[3][4] Strabo differentiated the Lusitanians from the Iberian tribes.[5] Pliny the Elder and Pomponius Mela distinguished the Lusitanians from neighboring Celtic groups in their geographical writings.[6]

The original Roman province of Lusitania briefly included the territories of Asturia and Gallaecia, but these were soon ceded to the jurisdiction of the Provincia Tarraconensis in the north, while the south remained the Provincia Lusitania et Vettones. After this, Lusitania's northern border was along the Douro River, while its eastern border passed through Salmantica and Caesarobriga to the Anas (Guadiana) river.

Culture

Categorising Lusitanian culture generally, including the language, is proving difficult. Some believe it was essentially a pre-Celtic Iberian culture with substantial Celtic influences, while others argue that it was an essentially Celtic culture with strong indigenous pre-Celtic influences.

_01.jpg)

Religion

The Lusitanians worshiped various gods in a very diverse polytheism, using animal sacrifice. They represented their gods and warriors in rudimentary sculpture. Endovelicus was the most important god: his cult eventually spread across the Iberian peninsula and beyond, to the rest of the Roman Empire and his cult was maintained until the fifth century; he was the god of public health and safety. The goddess Ataegina was especially popular in the south; as the goddess of rebirth (spring), fertility, nature, and cure, she was identified with Proserpina during the Roman era.

Lusitanian mythology was heavily influenced or related to Celtic mythology.[7][8] Also well attested in inscriptions are the names Bandua, often with a second name linked to a locality such as Bandua Aetobrico, and Nabia, possibly a goddess of rivers and streams.[7]

Language

The Lusitanian language was a paleohispanic language that clearly belongs to the Indo-European family and may be related to the Celtiberian language.

The precise affiliation of the Lusitanian language inside Indo-European family is still in debate: there are those who endorse that it is a Celtic language with an obvious "celticity" to most of the lexicon, over many anthroponyms and toponyms.[9] A second theory relates Lusitanian with the Italic languages; based on a relation of the name of Lusitanian deities with other grammatical elements of the area.[10]

Tribes

The Lusitanians were a people formed by several tribes that lived between the rivers Douro and Tagus, in most of today's Beira and Estremadura regions of central Portugal, and some areas of the Extremadura region (Spain). They were a tribal confederation, not a single political entity; each tribe had its own territory and was independent, and formed by smaller clans. However, they had a cultural sense of unity and a common name for the tribes. Each tribe was ruled by its own tribal aristocracy and chief. Many members of the Lusitanian tribal aristocracy were warriors as happened in many other pre-Roman peoples of the Iron Age. Only when an external threat occurred did the different tribes politically unite, as happened at the time of the Roman conquest of their territory when Viriathus became the single leader of the Lusitanian tribes. Kaukainos (or Caucenus) was another important Lusitanian chief before the Roman conquest. He ruled the Lusitanians (before Viriathus) for some time, leading the tribes in the resistance against Carthaginian attempts of conquest, and was successful.

The known Lusitanian tribes were:

- Arabrigenses

- Aravi

- Coelarni/Colarni

- Interamnienses

- Lancienses

- Lancienses Oppidani

- Lancienses Transcudani

- Ocelenses Lancienses

- Meidubrigenses

- Paesuri - Douro and Vouga (Portugal)

- Palanti (according to some scholars, these tribes were Lusitanians and not Vettones)[11]

- Calontienses

- Caluri

- Coerenses

- Tangi

- Talures

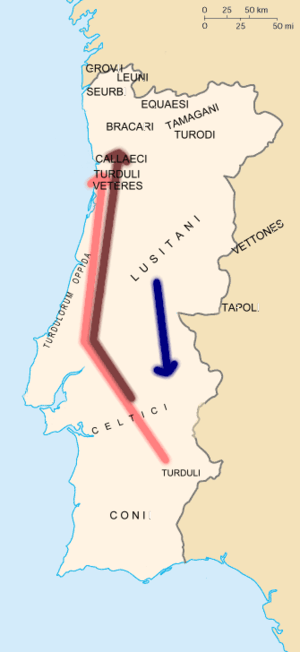

It remains to be known if the Turduli Veteres, Turduli Oppidani, Turduli Bardili, and Turduli were Lusitanian tribes (coastal tribes), were related Celtic peoples, or were instead related to the Turdetani (Celtic, pre-Celtic Indo-European, or Iberians) and came from the south. The name Turduli Veteres (older or ancient Turduli), a tribe that dwelt in today's Aveiro District, seems to indicate they came from the north and not from the south (contrary to what is assumed on the map). Several Turduli peoples or tribes possibly originally were not Lusitanians, but instead were Callaeci tribes that came from the north towards the south along the coast and then migrated inland along the Tagus and the Anas (Guadiana River) valleys.

More Lusitanian tribes are likely, but their names are unknown.

Warfare

The Lusitanians were considered by historians to be particularly adept at guerrilla warfare. The strongest amongst them were selected to defend the populace in mountainous sites.[12] They used hooked saunions made of iron, and wielded swords and helmets like those of the Celtiberians. They threw their darts from some distance, yet often hit their marks and wounded them deeply. Being active and nimble warriors, they would pursue their enemies and decapitate them. In times of peace, they had a particular style of dancing, which required great agility and nimbleness of the legs and thighs. In times of war, they marched in time, until they were ready to charge the enemy.[13]

Apiano claims that when Praetor Brutus sacked Lusitania after chasing Viriathus, the women fought valiantly next to their men.[3]

_02.jpg)

War with Rome

Since 193 BC, the Lusitanians had been fighting the Romans. In 150 BC, they were defeated by Praetor Servius Galba: springing a clever trap, he killed 9,000 Lusitanians and later sold 20,000 more as slaves in Gaul (modern France). Three years later (147 BC), Viriathus became the leader of the Lusitanians, and severely damaged the Roman rule in Lusitania and beyond. In 139 BC, Viriathus was betrayed and killed in his sleep by his companions (who had been sent as emissaries to the Romans), Audax, Ditalcus and Minurus, bribed by Marcus Popillius Laenas. However, when the three returned to receive their reward from the Romans, the Consul Servilius Caepio ordered their execution, declaring, "Rome does not pay traitors".

Romanization

After the death of Viriatus, the Lusitanians kept fighting under the leadership of Tautalus (Greek: Τάυταλος), but gradually acquired Roman culture and language; the Lusitanian cities, in a manner similar to those of the rest of the Romanised Iberian peninsula, eventually gained the status of "Citizens of Rome".

The Portuguese language is a local evolution of the Roman language, Latin.

Contemporary meaning

Lusitanians are often used by Portuguese writers as a metaphor for the Portuguese people, and similarly, Lusophone is used to refer to a Portuguese speaker.

Lusophone is at present a term used to categorize persons who share the linguistic and cultural traditions of the Portuguese-speaking nations and territories of Portugal, Brazil, Macau, Timor-Leste, Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, Guinea Bissau and others.

See also

- History of Portugal

- Timeline of Portuguese history

- Beira Alta

- Beira Baixa

- Ribatejo

- Alentejo

- Extremadura

- Emerita Augusta, capital of the Roman province of Lusitania ( Lusitaniae et Vetoniae)

- Hispania

- Lusitania (Roman province)

- Pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula

- List of Celtic tribes

- List of Celtic place names in Portugal

- List of Ancient Peoples of Portugal

- Roman Empire

Notes

- ↑ http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Frontinus/Strategemata/2*.html|Sextus Julius Frontinus. Stratagems: Book II. V. On Ambushes

- ↑ http://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/classical_diodorus.html#B5|Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheka Historia: The Historical Library. Book V: Britain, Gaul, and Iberia.

- 1 2 Luciano Pérez Vilatela. Lusitania: historia y etnología, p. 14, at Google Books (Spanish). [S.l.]: Real Academia de la Historia, 2000. 33 p. vol. 6 of Bibliotheca archaeologica hispana, v. 6 of Publicaciones del Gabinete de Antigüedades.

- ↑ André de Resende. As Antiguidades da Lusitânia, p. 94, at Google Books (Portuguese). [S.l.]: Imprensa da Univ. de Coimbra. 94 p.

- ↑ http://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=176646|José María Gómez Fraile. (1999). "Los coceptos de "Iberia" e "ibero" en Estrabon" (PDF) (in Spanish). SPAL: Revista de prehistoria y arqueología de la Universidad de Sevilla (8): 159-188.)

- ↑ Among them the Praestamarci, Supertamarci, Nerii, Artabri, and in general all people living by the seashore except for the Grovi of southern Galicia and northern Portugal: 'Totam Celtici colunt, sed a Durio ad flexum Grovi, fluuntque per eos Avo, Celadus, Nebis, Minius et cui oblivionis cognomen est Limia. Flexus ipse Lambriacam urbem amplexus recipit fluvios Laeron et Ullam. Partem quae prominet Praesamarchi habitant, perque eos Tamaris et Sars flumina non longe orta decurrunt, Tamaris secundum Ebora portum, Sars iuxta turrem Augusti titulo memorabilem. Cetera super Tamarici Nerique incolunt in eo tractu ultimi. Hactenus enim ad occidentem versa litora pertinent. Deinde ad septentriones toto latere terra convertitur a Celtico promunturio ad Pyrenaeum usque. Perpetua eius ora, nisi ubi modici recessus ac parva promunturia sunt, ad Cantabros paene recta est. In ea primum Artabri sunt etiamnum Celticae gentis, deinde Astyres.', Pomponius Mela, Chorographia, III.7-9.

- 1 2 Pedreño, Juan Carlos Olivares (2005). "Celtic Gods of the Iberian Peninsula". Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ↑ Quintela, Marco V. García (2005). "Celtic Elements in Northwestern Spain in Pre-Roman times". Center for Celtic Studies, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ↑ Wodtko, Dagmar S (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 11: The Problem of Lusitanian. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. pp. 335–367. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- ↑ Blanca María Prósper (2003). "The inscription of Cabeço das Fráguas revisited. Lusitanian and Alteuropäisch populations in the West of the Iberian Peninsula". Transactions of the Philological Society. 97 (2): 151–184. doi:10.1111/1467-968X.00047.

- ↑ Alarcão, Jorge de (2001). "Novas perspectivas sobre os Lusitanos (e outros mundos)" (PDF). Revista portuguesa de Arqueologia. 4 (2): 293–349 [p. 312 e segs]. ISSN 0874-2782.

- ↑ http://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/classical_diodorus.html#B5

- ↑ Hispaniae: Spain and the Development of Roman Imperialism, 218-82 BC, p. 100, at Google Books

References

- Ángel Montenegro et alii, Historia de España 2 - colonizaciones y formación de los pueblos prerromanos (1200-218 a.C), Editorial Gredos, Madrid (1989) ISBN 84-249-1386-8

- Alarcão, Jorge de, O Domínio Romano em Portugal, Publicações Europa-América, Lisboa (1988) ISBN 972-1-02627-1

- Alarcão, Jorge de et alii, De Ulisses a Viriato – O primeiro milénio a.C., Museu Nacional de Arqueologia, Instituto Português de Museus, Lisboa (1996) ISBN 972-8137-39-7

- Amaral, João Ferreira do & Amaral, Augusto Ferreira do, Povos Antigos em Portugal – paleontologia do território hoje Português, Quetzal Editores, Lisboa (1997) ISBN 972-564-224-4

Further reading

- Alvarado, Alberto Lorrio J., Los Celtíberos, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Murcia (1997) ISBN 84-7908-335-2

- Berrocal-Rangel, Luis, Los pueblos célticos del soroeste de la Península Ibérica, Editorial Complutense, Madrid (1992) ISBN 84-7491-447-7

- Burillo Mozota, Francisco, Los Celtíberos, etnias y estados, Crítica, Barcelona (1998, revised edition 2007) ISBN 84-7423-891-9

External links

- Detailed map of the Pre-Roman Peoples of Iberia (around 200 BC)

- Unknown ancient author text (about Julius Caesar in Hispania) of De Bello Hispaniensi (Spanish War).

- Pliny the Elder text of Naturalis Historia (Natural History), books 3-6 (Geography and Ethnography).

- Strabo's text of De Geographica (The Geography).