Medium wave

Medium wave (MW) is the part of the medium frequency (MF) radio band used mainly for AM radio broadcasting. For Europe the MW band ranges from 526.5 kHz to 1606.5 kHz,[1] using channels spaced every 9 kHz, and in North America an extended MW broadcast band goes from 535 kHz to 1705 kHz,[2] using 10 kHz spaced channels.

Propagation characteristics

Wavelengths in this band are long enough that radio waves are not blocked by buildings and hills and can propagate beyond the horizon following the curvature of the Earth; this is called the groundwave. Practical groundwave reception typically extends to 200–300 miles, with longer distances over terrain with higher ground conductivity, and greatest distances over salt water. Most broadcast stations use groundwave to cover their listening area.

Medium waves can also reflect off charged particle layers in the ionosphere and return to Earth at much greater distances; this is called the skywave. At night, especially in winter months and at times of low solar activity, the ionospheric D layer virtually disappears. When this happens, MF radio waves can easily be received many hundreds or even thousands of miles away as the signal will be reflected by the higher F layer. This can allow very long-distance broadcasting, but can also interfere with distant local stations. Due to the limited number of available channels in the MW broadcast band, the same frequencies are re-allocated to different broadcasting stations several hundred miles apart. On nights of good skywave propagation, the skywave signals of distant station may interfere with the signals of local stations on the same frequency. In North America, the North American Regional Broadcasting Agreement (NARBA) sets aside certain channels for nighttime use over extended service areas via skywave by a few specially licensed AM broadcasting stations. These channels are called clear channels, and they are required to broadcast at higher powers of 10 to 50 kW.

Use in the Americas

Initially broadcasting in the United States was restricted to two wavelengths: "entertainment" was broadcast at 360 meters (833 kHz), with stations required to switch to 485 meters (619 kHz) when broadcasting weather forecasts, crop price reports and other government reports.[3] This arrangement had numerous practical difficulties. Early transmitters were technically crude and virtually impossible to set accurately on their intended frequency and if (as frequently happened) two (or more) stations in the same part of the country broadcast simultaneously the resultant interference meant that usually neither could be heard clearly. The Commerce Department rarely intervened in such cases but left it up to stations to enter into voluntary timesharing agreements amongst themselves. The addition of a third "entertainment" wavelength, 400 meters,[3] did little to solve this overcrowding.

In 1923, the Commerce Department realized that as more and more stations were applying for commercial licenses, it was not practical to have every station broadcast on the same three wavelengths. On 15 May 1923, Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover announced a new bandplan which set aside 81 frequencies, in 10 kHz steps, from 550 kHz to 1350 kHz (extended to 1500, then 1600 and ultimately 1700 kHz in later years). Each station would be assigned one frequency (albeit usually shared with stations in other parts of the country and/or abroad), no longer having to broadcast weather and government reports on a different frequency than entertainment. Class A and B stations were segregated into sub-bands.[4]

Nowadays in most of the Americas, mediumwave broadcast stations are separated by 10 kHz and have two sidebands of up to ±5 kHz in theory, although in practice stations transmit audio of up to 10 kHz.[5] In the rest of the world, the separation is 9 kHz, with sidebands of ±4.5 kHz. Both provide adequate audio quality for voice, but are insufficient for high-fidelity broadcasting, which is common on the VHF FM bands. In the US and Canada the maximum transmitter power is restricted to 50 kilowatts, while in Europe there are medium wave stations with transmitter power up to 2 megawatts daytime.[6]

Most United States AM radio stations are required by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to shut down, reduce power, or employ a directional antenna array at night in order to avoid interference with each other due to night-time only long-distance skywave propagation (sometimes loosely called ‘skip’). Those stations which shut down completely at night are often known as "daytimers". Similar regulations are in force for Canadian stations, administered by Industry Canada; however, daytimers no longer exist in Canada, the last station having signed off in 2013, after migrating to the FM band.

Use in Europe

In Europe, each country is allocated a number of frequencies on which high power (up to 2 MW) can be used; the maximum power is also subject to international agreement by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU).[7] In most cases there are two power limits: a lower one for omnidirectional and a higher one for directional radiation with minima in certain directions. The power limit can also be depending on daytime and it is possible, that a station may not work at nighttime, because it would then produce too much interference. Other countries may only operate low-powered transmitters on the same frequency, again subject to agreement. For example, Russia operates a high-powered transmitter, located in its Kaliningrad exclave and used for external broadcasting, on 1386 kHz. The same frequency is also used by low-powered local radio stations in the United Kingdom, which has approximately 250 medium-wave transmitters of 1 kW and over;[8] other parts of the United Kingdom can still receive the Russian broadcast. International mediumwave broadcasting in Europe has decreased markedly with the end of the Cold War and the increased availability of satellite and Internet TV and radio, although the cross-border reception of neighbouring countries' broadcasts by expatriates and other interested listeners still takes place.

Due to the high demand for frequencies in Europe, many countries operate single frequency networks; in Britain, BBC Radio Five Live broadcasts from various transmitters on either 693 or 909 kHz. These transmitters are carefully synchronized to minimize interference from more distant transmitters on the same frequency.

Overcrowding on the Medium wave band is a serious problem in parts of Europe contributing to the early adoption of VHF FM broadcasting by many stations (particularly in Germany). However, in recent years several European countries (Including Ireland, Poland and, to a lesser extent Switzerland) have started moving away from Medium wave altogether with most/all services moving exclusively to other bands (usually VHF).

In Germany, almost all Medium wave public-radio broadcasts were discontinued between 2012 and 2015 to cut costs and save energy,[9] with the last such remaining programme (Deutschlandradio) being switched off on 31st December 2015.[10]

Stereo and digital transmissions

Stereo transmission is possible and offered by some stations in the U.S., Canada, Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Paraguay, Australia, The Philippines, Japan, South Korea, South Africa, and France. However, there have been multiple standards for AM stereo. C-QUAM is the official standard in the United States as well as other countries, but receivers that implement the technology are no longer readily available to consumers. Used receivers with AM Stereo can be found. Names such as "FM/AM Stereo" or "AM & FM Stereo" can be misleading and usually do not signify that the radio will decode C-QUAM AM stereo, whereas a set labeled "FM Stereo/AM Stereo" or "AMAX Stereo" will support AM stereo.

In September 2002, the United States Federal Communications Commission approved the proprietary iBiquity in-band on-channel (IBOC) HD Radio system of digital audio broadcasting, which is meant to improve the audio quality of signals. The Digital Radio Mondiale (DRM) IBOC system has been approved by the ITU for use outside North America and U.S. territories. Some HD Radio receivers also support C-QUAM AM stereo, although this feature is usually not advertised by the manufacturer.

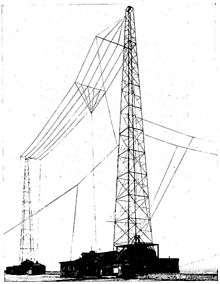

Antennas

For broadcasting, mast radiators are the most common type of antenna used, consisting of a steel lattice guyed mast in which the mast structure itself is used as the antenna. Stations broadcasting with low power can use masts with heights of a quarter-wavelength (about 310 millivolts per meter using one kilowatt at one kilometer) to 5/8 wavelength (225 electrical degrees; about 440 millivolts per meter using one kilowatt at one kilometer), while high power stations mostly use half-wavelength to 5/9 wavelength. The usage of masts taller than 5/9 wavelength (200 electrical degrees; about 410 millivolts per meter using one kilowatt at one kilometer) with high power gives a poor vertical radiation pattern, and 195 electrical degrees (about 400 millivolts per meter using one kilowatt at one kilometer) is generally considered ideal in these cases. Usually mast antennas are series-excited (base driven); the feedline is attached to the mast at the base, so the base of the antenna is at high electrical potential and must be supported on a ceramic insulator to insulate it from the ground. Shunt-excited masts, in which the base of the mast is at a node of the standing wave at ground potential and so does not need to be insulated from the ground have fallen into disuse, except in cases of exceptionally high power, 1 MW or more, where series excitement might be impractical. If grounded masts or towers are required, then cage aerials or long-wire aerials are used. Another possibility consists of feeding the mast or the tower by cables running from the tuning unit to the guys or crossbars in a certain height.

Directional aerials consist of multiple masts, which need not to be from the same height. It is also possible to realize directional aerials for mediumwave with cage aerials where some parts of the cage are fed with a certain phase difference.

For medium-wave (AM) broadcasting, quarter-wave masts are between 153 feet (47 m) and 463 feet (141 m) high, depending on the frequency. Because such tall masts can be costly and uneconomic, other types of antennas are often used, which employ capacitive top-loading (electrical lengthening) to achieve equivalent signal strength with vertical masts shorter than a quarter wavelength.[11] A "top hat" of radial wires is occasionally added to the top of mast radiators, to allow the mast to be made shorter. For local broadcast stations and amateur stations of under 5 kW, T- and L-antennas are often used, which consist of one or more horizontal wires suspended between two masts, attached to a vertical radiator wire. A popular choice for lower-powered stations is the umbrella antenna, which needs only one mast one tenth wavelength or less in height. This antenna uses a single mast insulated from ground and fed at the lower end against ground. At the top of the mast, radial top-load wires are connected (usually about six) which slope downwards at an angle of 40-45 degrees as far as about one-third of the total height, where they are terminated in insulators and thence outwards to ground anchors. Thus the umbrella antenna uses the guy wires as the top-load part of the antenna. In all these antennas the smaller radiation resistance of the short radiator is increased by the capacitance added by the wires attached to the top of the antenna.

In some rare cases dipole antennas are used, which are slung between two masts or towers. Such antennas are intended to radiate a skywave. The medium-wave transmitter at Berlin-Britz for transmitting RIAS used a cross dipole mounted on five 30.5 metre high guyed masts to transmit the skywave to the ionosphere at nighttime.

Receiving antennas

Because at these frequencies atmospheric noise is far above the receiver signal to noise ratio, inefficient antennas much smaller than a wavelength can be used for receiving. For reception at frequencies below 1.6 MHz, which includes long and medium waves, loop antennas are popular because of their ability to reject locally generated noise. By far the most common antenna for broadcast reception is the ferrite-rod antenna, also known as a loopstick antenna. The high permeability ferrite core allows it to be compact enough to be enclosed inside the radio's case and still have adequate sensitivity.

See also

- Medium frequency band

- AM radio

- Longwave

- MW DX

- Shortwave

- FM radio

- Satellite radio

- List of European medium wave transmitters

- Wave plan of Geneva

- DAB Radio

References

- ↑ "United Kingdom Frequency Allocation Table 2008" (PDF). Ofcom. p. 21. Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- ↑ "U.S. Frequency Allocation Chart" (PDF). National Telecommunications and Information Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. October 2003. Retrieved 2009-08-11.

- 1 2 "Building the Broadcast Band". Earlyradiohistory.us. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ↑ Christopher H. Sterling; John M. Kittross (2002). Stay tuned: a history of American broadcasting. Psychology Press. p. 95. ISBN 0-8058-2624-6.

- ↑ "Subpart A: AM Broadcast Stations, Sec. 73.44 AM transmission system emission limitations". TITLE 47--TELECOMMUNICATION, CHAPTER I--FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION (CONTINUED), PART 73_RADIO BROADCAST SERVICES. U.S. Government Printing Office. Revised as of October 1, 2006. Archived from the original on October 25, 2011. Retrieved 2009-04-24. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "MWLIST quick and easy: Europe, Africa and Middle East". Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ↑ "International Telecommunication Union". ITU. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- ↑ "MW channels in the UK". Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ↑ "Fast alle ARD-Radiosender stellen Mittelwelle ein". heise.de. 2015-01-06. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- ↑ Heumann, Marcus (2015-12-17). "Abschied von der Mittelwelle. Der gefürchtete Wellensalat ist Geschichte". Deutschlandfunk.de. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- ↑ Weeks, W.L 1968, Antenna Engineering, McGraw Hill Book Company, Section 2.6

External links

- "Building the Broadcast Band" the development of the 520-1700 kHz MW (AM) band

- M3 Map of Effective Ground Conductivity in the USA

- MWLIST worldwide database of MW and LW stations

- www.mwcircle.org The Medium Wave Circle. A UK-based club for Medium wave DX'ers and enthusiasts.

- - List of long- and mediumwave transmitters with GoogleMap-Links to transmission sites