Machi (shaman)

A machi is a traditional healer and religious leader in the Mapuche culture of Chile and Argentina. Machis play significant roles in Mapuche religion. Women are more commonly machis than men.

Description

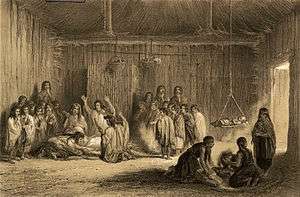

As a religious authority, a machi leads healing ceremonies, called Machitun. During the machitun, the machi communicates with the spirit world. Machies also serve as advisors, and oracles for their community. In the past, they advised on peace and warfare.

The term is sometimes interchangeable with the word kalku, however, kalku has a usually evil connotation whereas machi is usually considered good; this, however, is not always true since in common use the terms may be interchanged.

The Mapuches live in southern South America mostly in central Chile (Araucanía and Los Lagos) and the adjacent areas of Argentina.

To become a machi, a Mapuche person has to demonstrate character, willpower, and courage, because initiation is long and painful. Usually a person is selected in infancy, based upon the following:

- premonitory dreams

- supernatural revelations

- influence of the family

- inheritance

- her or his power of healing disease

- own initiative

Machiluwun is the ceremony to consecrate a new machi. The chosen child will live six months with a dedicated machi, where he or she learns the skills to serve as a machi.

Role in Mapuche medicine

The machi is a person of great wisdom and healing power and is the main character of Mapuche medicine. The machi has detailed knowledge of medicinal herbs and other remedies, and is also said to have the power of the spirits and the ability to interpret dreams, called peumo in Mapudungun. Machis are also said to help communities identify witches or other individuals who are using supernatural powers to do harm.

Mapuche traditional medicine is gaining more acceptance in the broader Chilean society.

Controversy

A modern ritual human sacrifice occurred during the devastating earthquake and tsunami of 1960 by a machi of the Mapuche in the Lago Budi community.[1] The victim, five-year-old José Luis Painecur, had his arms and legs removed by Juan Pañán and Juan José Painecur (the victim's grandfather), and was stuck into the sand of the beach like a stake. The waters of the Pacific Ocean then carried the body out to sea. The sacrifice was rumored to be at the behest of local machi, Juana Namuncurá Añen. The two men were charged with the crime and confessed, but later recanted. They were released after two years. A judge ruled that those involved in these events had "acted without free will, driven by an irresistible natural force of ancestral tradition." The arrested men's explanation was: "We were asking for calm in the sea and on the earth."[2]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Patrick Tierney, The Highest Altar: Unveiling the Mystery of Human Sacrifice (1989) ISBN 978-0-14-013974-7

- ↑ "Asking for Calm." Time Magazine. 4 July 1960 (retrieved 28 June 2011)

References

- Ana Mariella Bacigalupo.Shamans of the foye tree: gender, power, and healing among Chilean Mapuche. University of Texas Press, 2007. ISBN 0-292-71659-1, ISBN 978-0-292-71659-9

- Francisco Núñez de Pineda y Bascuñán, CAUTIVERIO FELIZ, Y RAZÓN DE LAS GUERRAS DILATADAS DE CHILE, CAPITULO XIX En que se refiere lo que el dia siguiente hicimos, y lo que vimos hacer a un machi, que son hechiceros y curan por arte del demonio, y de la suerte que se apodera de ellos, con las cerimonias (sic) que se dirán; Coleccíon de historiadores de Chile y documentos relativos a la historia nacional, Tomo III, Sociedad Chilena de Historia y Geografía, Instituto Chileno de Cultura Hispánica, Academia Chilena de la Historia, Imprenta del Ferrocarril, Santiago, 1863. Original from Harvard University, Digitized May 18, 2007.

- Juan Ignacio Molina, The Geographical, Natural, and Civil History of Chile, pg. 105-109

- Ana Mariella Bacigalupo, The Struggle for Machi Masculinity