Mahmoud Dowlatabadi

| Mahmoud Dowlatabadi | |

|---|---|

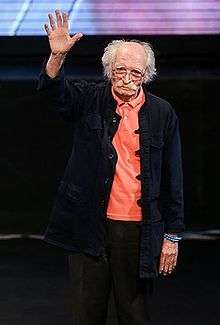

Mahmoud Dowlatabadi - May 2016 | |

| Born |

1 August 1940 Sabzevar, Iran |

| Occupation | Writer, Actor |

| Nationality | Iranian |

| Literary movement | Persian literature |

| Notable works | |

| Notable awards |

Man Asian Literary Prize Jan Michalski Prize for Literature Legion of Honour |

| Spouse | Mehr Azad Maher (m. 1966) |

| Children |

Siavash (b. 1967) Farhad (b. 1969) Sara (b. 1970) |

| Relatives |

Abdolrasoul Dowlatabadi (Father) Fatemeh Dowlatabadi (Mother) |

| Website | |

|

www | |

Mahmoud Dowlatabadi (Persian: محمود دولتآبادی, Mahmud Dowlatâbâdi) (born 1 August 1940 in Dowlatabad, Sabzevar) is an Iranian writer and actor, known for his promotion of social and artistic freedom in contemporary Iran and his realist depictions of rural life, drawn from personal experience.

Biography

In 1940, Mahmoud Dowlatabadi was born to a poor shoemaker in Dowlatabad, a remote village in the Sabzevar, the northwestern part of Khorasan Province, Iran.[1] He worked as a farmhand and attended Mas'ud Salman Elementary School, where he learned to read. Books were a revelation to the young boy. "I read all the romances that we had at that time around the village," he said in an interview.[2] "I would read on the roof of the house with a lamp…I read War and Peace that way." Though his father had little formal education, he introduced Dowlatabadi to the Persian Classical poets, Saadi Shirazi, Hafez, and Ferdowsi. "[My father] generally spoke in the kind of language they used," Dowlatabadi said.

Nahid Mozaffari, who edited a PEN anthology of Iranian literature, said of Dowlatabad, "He has an incredible memory of folklore, which might come from his days as an actor or might come from his origins, as somebody who didn't have a formal education, who learned things by memorizing the local poetry and hearing the local stories."[1]

As a teenager, Dowlatabadi took up a trade like his father and opened a shop. One afternoon, he found himself hopelessly bored. He closed the shop, gave the key to a boy, and told him to tell his father, "Mahmoud's left." He caught a ride to Mashhad, where he worked for a year before leaving for Tehran to pursue theatre. There Dowlatabadi worked for a year before he could afford to take theatre classes. When he did, he rose to the top of his class, still working numerous other jobs. He was an actor---and a shoemaker, barber, bicycle repairman, street barker, cotton picker, and cinema ticket taker. Around this time he also ventured into journalism, fiction, and screenplays. "Whenever I was done with work and wasn't preoccupied with finding food and so on, I would sit down and just write," he said.[2]

In addition to his performance in plays by Brecht (e.g. The Visions of Simone Machard), Arthur Miller (e.g. A View from the Bridge) and Bahram Beyzai (e.g. The Marionettes), Dowlatabad's novels attracted the attention of local police. In 1974 he was arrested by the Savak, the shah's secret police force. When he wondered exactly what crime he committed, they told him, "None, but everyone we arrest seems to have copies of your novels so that makes you provocative to revolutionaries."[1] He was in prison for two years.

Toward the end of his term, Dowlatabadi said, "The story of Missing Soluch came to me all at once, and I wrote the entire work in my head." Dowlatabadi couldn't write anything down while in prison. "I began to become restless," he said. "One of the other prisoners...said to me, 'You used to be so good at putting up with prison, now why're you so anxious?' And I replied that my anxiety wasn't related to prison and all that came with it, but was because of something entirely else. I had to write this book." When he was finally released, he wrote Missing Soluch in 70 nights.[2] It later became his first novel published in English, preceding The Colonel.[3]

Works

Kelidar

Kelidar is a saga about a Kurdish nomadic family that spans 10 books and 3,000 pages. Encyclopædia Iranica praises its "heroic, lyrical, and sensual" language. The story is tremendously popular among Iranians due to "its detailed portrayal of political and social upheaval."[1] Dowlatabadi spent over a decade crafting the tale. "I spent fifteen years preparing, writing short stories, sometimes writing works that were a little longer, the grounds towards what would become Kelidar," he said.[2]

Missing Soluch

In Missing Soluch, an impoverished woman raises her children in an isolated village after the unexplained disappearance of her husband, Soluch. Though the idea for the novel first came to Dowlatabadi in prison, its origins trace back to his childhood. "My mother used to talk about a woman in the village whose husband had disappeared and had left her alone. She was left to raise several children on her own. Since she didn't want the village to pity her, she would take a bit of lamb's fat and melt it and then toss a handful of dry grass or something into the pan and put this in the oven, so that with the smoke that would come out of the oven the neighbors might think that she was cooking a meat stew for her children that night," he told an interviewer. Missing Soluch was his first work translated into English.[2]

The Colonel

The Colonel is a novel about nation, history, and family, beginning on a rainy night when two policemen summon the Colonel to collect the tortured body of his daughter, a victim of the Islamic Revolution.[3] Dowlatabadi wrote the novel in the 1980s, when intellectuals were in danger of execution. "I hid it in a drawer when I finished it," he said.[1] Though it is published abroad in English, the novel is not available in Iran, in Persian. "I did not even want to have this on their radar," he said. "Either they would take me to prison or prevent me from working. They would have their ways." The novel was first published in Germany, later in the UK and United States.[1]

Thirst

Thirst (Persian: Besmel) is a novel of the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988). It is written mostly from the perspective of an Arabic-writing Iraqi. The original Persian title refers to the concept of 'besmel' explained in a footnote as: "the supplication required in Islam before the sacrifice of any animal". It is used repeatedly in the text, as the characters find it applies to them.[4]

Influence

Dowlatabadi is celebrated as one of the most important writers in contemporary Iran, particularly for his use of language. He elevates rural speech, drawing on the rich, lyrical tradition of Persian poetry. He "examines the complexities and moral ambiguities of the experience of the poor and forgotten, mixing the brutality of that world with the lyricism of the Persian language," said Kamran Rastegar, a translator of Dowlatabadi's work.[1] When Tom Patterdale translated Dowlatabadi's The Colonel, he avoided Latinate English words in favor of Anglo-Saxon ones, hoping to reproduce the effect Dowlatabadi's "rough and ready" prose.[5] Most other Iranian writers come from solidly middle-class backgrounds, with urban educations. Because of his rural background, Dowlatabadi stands out as a unique voice. He has also garnered praise internationally, with Kirkus Reviews calling The Colonel, "A demanding and richly composed book by a novelist who stands apart."[6] The Independent described the novel as "passionate," and emphasized, "It's about time that everyone even remotely interested in Iran read this novel." [7]

Awards and honors

- 2009 Haus der Kulturen Berlin International Literary Award, shortlist, The Colonel

- 2011 Man Asian Literary Prize, longlist, The Colonel

- 2012 Hooshang Golshiri Literary Award, Lifetime Achievement[8]

- 2013 Jan Michalski Prize for Literature, winner, The Colonel[9][10][11]

- 2014 Legion of Honour

In August 2014, Iran issued a commemorative postage stamp for writer Mahmoud Dowlatabadi.[12]

Translations

- In Norway, Missing Soluch was translated into Norwegian by N. Zandjani as Den tomme plassen etter Soluch. Oslo, Solum forlag 2008.

- In Switzerland, Kelidar was translated into German by Sigrid Lotfi, Unionsverlag 1999.

- In Switzerland, The Colonel was translated into German by Bahman Nirumand, Unionsverlag, 2009. Later, it was translated to English and Italian.

- In Israel, The Colonel was translated into Hebrew by Orly Noy as "שקיעת הקולונל" (The Decline of the Colonel) translated. Am Oved Publishing, 2012.

- In the United States, Missing Soluch was translated into English by Kamran Rastegar, 2007.

- In the United Kingdom, The Colonel was translated into English by Tom Patterdale, 2012.

- In the United Kingdom, Thirst was translated into English by Martin E. Weir, 2014.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 An Iranian Storyteller’s Personal Revolution. Larry Rohter. New York Times. July 1, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Interview with Mahmoud Dowlatabadi

- 1 2 Haus Publishing. The Colonel

- ↑ Michael Orthofer (August 2014). "Thirst by Mahmoud Dowlatabadi". complete review. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ↑ The Three Percent, a blog on translation. University of Rochester

- ↑ Kirkus Reviews. The Colonel

- ↑ The Independent review of The Colonel

- ↑ Of Six Directions, "12th Golshiri Literary Awards Wrap Up", Farzaneh Doosti blog, Feb. 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Edition 2013". Jan Michalski Foundation. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ↑ M.A.O. (September 14, 2013). "Jan Michalski Prize shortlist". complete review. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ↑ Sal Robinson (November 14, 2013). "Mahmoud Dowlatabadi wins the 2013 Jan Michalski Prize". Melville House Publishing. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Iran issues commemorative postage stamp for writer Mahmud Dowlatabadi". Tehran Times. August 9, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mahmoud Dowlatabadi. |

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Interview with Mahmoud Dowlatabadi, Tehran 2006.

- An Iranian Storyteller’s Personal Revolution, New York Times profile by Larry Rohter, July 1, 2012