Marie Lloyd

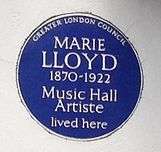

Matilda Alice Victoria Wood, (12 February 1870 – 7 October 1922), professionally known as Marie Lloyd /ˈmɑːri/;[1] was an English music hall singer, comedian and musical theatre actress during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. She was best known for her performances of songs such as "The Boy I Love Is Up in the Gallery", "My Old Man (Said Follow the Van)" and "Oh Mr Porter What Shall I Do". She received both criticism and praise for her use of innuendo and double entendre during her performances, but enjoyed a long and prosperous career, during which she was affectionately called the "Queen of the Music Hall".

Born in London, she was showcased by her father at the Eagle Tavern in Hoxton. In 1884, she made her professional début as Bella Delmere; she changed her stage name to Marie Lloyd the following year. In 1885, she had success with her song "The Boy I Love Is Up in the Gallery", and she frequently topped the bill at prestigious theatres in London's West End. In 1891, she was recruited by the impresario Augustus Harris to appear in that year's spectacular Theatre Royal, Drury Lane Christmas pantomime Humpty Dumpty. She starred in a further two productions at the theatre, Little Bo Peep (1892) and Robinson Crusoe (1893). By the mid-1890s, Lloyd was in frequent dispute with Britain's theatre censors due to the risqué content of her songs.

Between 1894 and 1900, she became an international success when she toured France, America, Australia and Belgium with her solo music hall act. In 1907, she assisted other performers during the music hall war and took part in demonstrations outside theatres, protesting for better pay and conditions for performers. During the First World War, in common with most other music hall artists, she supported recruitment into the armed services to help the war effort, touring hospitals and industrial institutions to help boost morale. In 1915, she performed her only wartime song "Now You've Got Your Khaki On", which became a favourite among front-line troops.

Lloyd had a turbulent private life that was often the subject of press attention: she was married three times, divorced twice, and frequently found herself giving court testimony against two of her husbands who had physically abused her. In later life, she was still in demand at music halls and had a late success in 1919 with her performance of "My Old Man (Said Follow the Van)", which became one of her most popular songs. Privately, she suffered from bouts of ill-health and became alcohol-dependent, both of which imposed restrictions on her performing career by the 1920s. In 1922, she gave her final performance at the Alhambra Theatre, London, during which she became ill on stage. She died a few days later at the age of 52.

Biography

Family background and early life

Lloyd was born on 12 February 1870 in Hoxton, London. Her father John Wood (1847–1940), was an artificial flower arranger and waiter, and his wife Matilda Mary Caroline née Archer (1849–1931), was a dressmaker and costume designer.[n 1] Lloyd was the eldest of nine children[3] and became known within the family circle as Tilley.[4][n 2] The Wood family were respectable, hard-working,[7] and financially comfortable. Lloyd often took career advice from her mother, whose influence was strong in the family. Lloyd attended a school in Bath Street, London, but disliked formal education and often played truant;[8] with both her parents working, she adopted a maternal role over her siblings, helping to keep them entertained, clean and well cared-for.[9] Along with her sister Alice, she arranged events in which the Wood children performed at the family home.[10] She enjoyed the experience of entertaining her family and decided to form a minstrel act in 1879 called the Fairy Bell troupe comprising her brothers and sisters.[11][n 3]

Lloyd and the troupe made their début at a mission in Nile Street, Hoxton, in 1880[3][12] and followed this with an appearance at the Blue Ribbon Gospel Temperance Mission later the same year. Costumed by Matilda,[3] they toured local doss-houses in East London, where they performed temperance songs, teaching people the dangers of alcohol abuse.[11][n 4] Eager to show off his daughter's talent, John secured her unpaid employment as a table singer at the Eagle Tavern in Hoxton, where he worked as a waiter.[13] Among the songs she performed there was "My Soldier Laddie".[14] Together with her performances at the Eagle, Lloyd briefly contributed to the family income by making babies' boots, and, later, curled feathers for hat making.[15] She was unsuccessful at both and was sacked from the latter after being caught dancing on the tables by the foreman. She returned home that evening and declared that she wanted a permanent career on the stage. Although happy to have her performing in her spare time, her parents initially opposed the idea of her appearing on the stage full-time. She recalled that when her parents "saw that they couldn't kick their objections as high as [she] could kick [her] legs, they very sensibly came to the conclusion to let things take their course and said 'Bless you my child, do what you like'."[16]

Early career and first marriage

On 9 May 1885, at the age of 15, Lloyd made her professional solo stage début at the Grecian music hall (in the same premises as the Eagle Tavern),[17] under the name "Matilda Wood".[18] She performed "In the Good Old Days" and "My Soldier Laddie",[18] which proved successful, and earned her a booking at the Sir John Falstaff music hall in Old Street where she sang a series of romantic ballads.[19] Soon after this, she chose the stage name Bella Delmere[20][n 5] and appeared on stage in costumes designed by her mother.[21] Her performances were a success, despite her singing other artists' songs without their permission,[16] a practice which brought her a threat of an injunction from one of the original performers.[22] News of her act travelled; that October, she appeared at the Collins music hall in Islington in a special performance to celebrate the theatre's refurbishment, the first time she had appeared outside Hoxton, and two months later, she was engaged at the Hammersmith Temple of Varieties and the Middlesex Music Hall in Drury Lane.[23] On 3 February 1886, she appeared at the prestigious Sebright Music Hall in Bethnal Green, where she met George Ware, a prolific composer of music hall songs. Ware became her agent and,[20] after a few weeks, she began performing songs purchased from little-known composers.[24] As her popularity grew, Ware suggested that she change her name. "Marie" was chosen for its "posh" and "slightly French" sound, and "Lloyd" was taken from an edition of Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper.[13][25]

Lloyd established her new name on 22 June 1886,[20] with an appearance at the Falstaff Music Hall, where she attracted wide notice for the song "The Boy I Love Is Up in the Gallery" (which was initially written for Nelly Power by Lloyd's agent George Ware).[25] By 1887, her performance of the song had become so popular that she was in demand in London's West End,[14] including the Oxford Music Hall, where she excelled at skirt dancing.[26] George Belmont, the Falstaff's proprietor, secured her an engagement at the Star Palace of Varieties in Bermondsey. She soon began making her own costumes, a skill she learned from her mother, and one she used for the rest of her career.[27] She undertook a month-long tour of Ireland at the start of 1886, earning £10 per week after which she returned to East London to perform at, amongst others, the Sebright Music Hall, Bethnal Green.[25][28][n 6] On 23 October, The Era called her "a pretty little soubrette who dances with great dash and energy."[29]

.jpg)

By the end of 1886, Lloyd was playing several halls a night[30] and earned £100 per week. She was now able to afford new songs from established music hall composers and writers,[31] including "Harry's a Soldier", "She Has a Sailor for a Lover", and "Oh Jeremiah, Don't you Go to Sea".[n 7] By 1887, Lloyd began to display a skill for ad lib, and to gain a reputation for her impromptu performances.[33] It was during this period that she first sang "Whacky-Wack" and "When you Wink the Other Eye", a song which introduced her famous wink at the audience.[27][34] Unlike her West End audiences who enjoyed her coarse humour, her "blue" performances did not impress audiences in the East End.[35]

While appearing at the Foresters music hall in Mile End, she met and began dating Percy Charles Courtenay,[36] a ticket tout from Streatham, London. The courtship was brief, and the couple married on 12 November 1887 at St John the Baptist, Hoxton.[n 8] In May 1888, Lloyd gave birth to a daughter, Marie (1888–1967).[3][n 9] The marriage was mostly unhappy, and Courtenay was disliked by Lloyd's family and friends. Before long, Courtenay became addicted to alcohol and gambling, and grew jealous of his wife's close friendship with the 13-year-old actress Bella Burge,[n 10] to whom Lloyd had rented a room in the marital house. He also became angry at the numerous parties Lloyd hosted for fellow members of the music hall profession including Gus Elen, Dan Leno and Eugene Stratton.[41][42]

In October 1888, Lloyd returned from maternity leave and joined rehearsals for the 1888–89 pantomime The Magic Dragon of the Demon Dell; or, The Search for the Mystic Thyme, in which she was cast as Princess Kristina. The production, which was staged between Boxing Day and February at the Britannia theatre in Hoxton, gave her the security of working close to home for a two-month period. The engagement also gave her much-needed experience of playing to a big audience.[43] The following year, she appeared at more Bohemian venues including the Empire and the Alhambra theatres, the Trocadero Palace of Varieties, and the Royal Standard playhouse.[44] In 1889, she gave birth to a stillborn child, which further damaged her marriage.[45]

By the start of the 1890s, Lloyd had built up a successful catalogue of songs, which included "What's That For, Eh?", about a little girl who asks her parents the meaning of various everyday household objects. Her biographer and theatre historian W. J. MacQueen-Pope described the song as being "blue" and thought that it spoke volumes about her reputation thanks to her "wonderful wink, and that sudden, dazzling smile, and the nod of the head."[46] Similar-styled songs followed; "She'd Never had her Ticket Punched Before", told the story of a young, naive woman travelling to London on her own by train. This was followed by "The Wrong Man Never Let a Chance go By"; "We Don't Want to Fight, But, by Jingo, If we Do";[46] "Oh You Wink the Other Eye"[47] and "Twiggy Vous"—a song which won her much success and increased her popularity abroad.[46] After an evening's performance at the Oxford music hall, a French well-wisher requested a conversation and to meet Lloyd backstage. Flanked by Courtenay, she appeared at the stage door, where Courtenay threatened the man with violence as both had become suspicious of his interest in her. She took a chance and invited the man into her dressing room, where he identified himself as a member of the French government. He confirmed to her that "Twiggy Vous" was "most popular in Paris"; she was delighted at the news.[48] At the end of the year, Lloyd returned to London where she appeared in the Christmas pantomime Cinderella in Peckham alongside her sister Alice.[49]

1890s

Drury Lane and success

Between 1891 and 1893, Lloyd was recruited by the impresario Augustus Harris to appear alongside Dan Leno in the spectacular and popular Theatre Royal, Drury Lane Christmas pantomimes.[n 11] While lunching with Harris in 1891 to discuss his offer, Lloyd played coy, deliberately confusing the theatre with the lesser known venue the Old Mo so as not to appear conscious of Drury Lane's successful reputation; she compared its structure to that of a prison. Secretly, she was thrilled with the offer,[51] for which she would receive £100 per week. The pantomime seasons lasted from Boxing Day to March[52] and were highly lucrative, but Lloyd found working from a script restrictive.[53] Her first role was Princess Allfair in Humpty Dumpty; or, The Yellow Dwarf and the Fair One,[51] which she dismissed as being "Bloody awful, eh?"[54] She received mixed reviews for her opening performance. The Times described her as being "playful in gesture, graceful in appearance, but not strong in voice."[51][55] Despite the weak start (which Lloyd blamed on nerves), the pantomime received glowing reviews from the theatrical press.[56] The London Entr'acte thought that she "delivere[d] her text quite pungently, and sings and dances with spirit too."[57] She was noted for her acrobatic dancing on stage, and was able to display handstands, tumbles and high kicks. As a boy, the writer Compton Mackenzie was taken to the show's opening night and admitted that he was "greatly surprised that any girl should have the courage to let the world see her drawers as definitely as Marie Lloyd."[58]

Lloyd's biographer Midge Gillies defines 1891 as being the year that she officially "made it" thanks to a catalogue of hit songs and major success in the halls and pantomime. When she appeared at the Oxford music hall in June, the audience cheered so loudly for her return that the following act could not be heard; The Era called her "the favourite of the hour".[59][60] During the summer months, she toured North England, including Liverpool, Birmingham and Manchester. At the last she stayed an extra six nights due to popular demand, which caused her to cancel a trip to Paris.[61] The 1892 pantomime was Little Bo Peep; or, Little Red Riding Hood and Hop O' My Thumb, in which she played Little Red Riding Hood.[62] The production was five hours long and culminated with the show's harlequinade.[63][n 12] During one scene, her improvisational skills caused some scandal when she got out of bed to pray, but instead reached for a chamber pot.[65][66] The stunt angered Harris, who ordered her not to do it again or risk immediate dismissal. Max Beerbohm, who was in a later audience, asked "Isn't Marie Lloyd charming and sweet in the pantomime? I think of little besides her."[67] On 12 January 1892, Lloyd and Courtenay brawled drunkenly in her Drury Lane dressing room after an evening's performance of Little Bo-Peep. Courtenay pulled a decorative sword off the wall and threatened to cut her throat; she escaped from the room with minor bruises and reported the incident to the Bow Street police station.[68][69] In early 1893, she travelled to Wolverhampton where she starred as Flossie in another unsuccessful piece called The A.B.C Girl; or, Flossie the Frivolous,[54] which, according to MacQueen-Pope, "ended the Queen of Comedy's career as an actress".[70][n 13]

Lloyd made her American stage début in 1893, appearing at Koster and Bial's Music Hall in New York. She sang "Oh You Wink the Other Eye", much to the delight of her American audiences. Other numbers were "After the Pantomime" and "You Should Go to France and See the Ladies Dance", which both required her to wear provocative costumes.[72] Her performances pleased the theatre proprietors, who presented her with an antique tea and coffee service.[27][n 14] News of her success reached home, and the London Entr'acte reported that "Miss Marie Lloyd made the biggest hit ever known at Koster and Bial's variety hall, New York."[74]

Upon her return to London, Lloyd introduced "Listen With the Right Ear", which was an intended follow-up to "Oh You Wink the Other Eye".[75] Shortly after her return, she sailed to France, to take up an engagement in Paris. Her biographer Daniel Farson thought that she received "greater acclaim than any other English comedienne who had preceded her".[76] She changed the lyrics to some of her best-known songs for her French audience and retitled them, "The Naughty Continong"; "Twiggy Vous"; "I'm Just Back from Paris" and "The Coster Honeymoon in Paris".[77][n 15] At Christmas in 1893, she returned to London to honour her final Drury Lane commitment, starring as Polly Perkins in Robinson Crusoe.[52][79][80] The part allowed her to perform "The Barmaid" and "The Naughty Continong" and saw her perform a mazurka with Leno.[81] Talking to a friend years later about her Drury Lane engagements, she admitted that she was "the proudest little woman in the world".[52]

In May 1894, Courtenay followed Lloyd to the Empire, Leicester Square, where she was performing, and attempted to batter her with a stick, shouting: "I will gouge your eyes out and ruin you!" His assault missed Lloyd, but struck Burge in the face instead. As a result of the incident, Lloyd was sacked from the Empire for fear of a reprisal.[82][n 16] Lloyd left the marital home, moving to 73 Carleton Road, Tufnell Park[84] and successfully applied for a restraining warrant, which prevented Courtenay from contacting her. A few weeks later, Lloyd began an affair with the music hall singer Alec Hurley,[42][n 17] which resulted in Courtenay initiating divorce proceedings in 1894 on the grounds of her adultery.[42][82] That year, together with a short tour of the English provinces, Lloyd travelled to New York with Hurley, where she appeared at the Imperial Theatre, staying for two months. On her return to England, she appeared in the Liverpool Christmas pantomime as the principal boy in Pretty Bo-Peep, Little Boy Blue, and the Merry Old Woman who lived in a Shoe. Her performance was praised by the press, who called her "delightfully easy, graceful and self-possessed."[86]

Risqué reputation and transatlantic tours

By 1895, Lloyd's risqué songs were receiving frequent criticism from theatre reviewers and influential feminists. As a result, she often experienced resistance from strict theatre censorship which dogged the rest of her career.[87] The writer and feminist Laura Ormiston Chant, who was a member of the Social Purity Alliance, disliked the bawdiness of music hall performances, and thought that the venues were attractive to prostitutes. Her campaign persuaded the London County Council to erect large screens around the promenade at the Empire Theatre in Leicester Square, as part of the licensing conditions.[88][89] The screens were unpopular and protesters, among them the young Winston Churchill, later pulled them down.[90][91] That November at the Tivoli theatre, Lloyd performed "Johnny Jones", a ditty about a girl who is taught the facts of life by her best male friend.[92] The song, although not lyrically obscene, was considered to be offensive largely because of the manner in which Lloyd sang it, adding winks and gestures, and creating a conspiratorial relationship with her audience. Social reformers cited "Johnny Jones" as being offensive, but less so compared to other songs of the day.[93] Upon the expiry of a music hall's entertainments licence, the Licensing Committee tried to use the lyrical content of music hall songs as evidence against a renewal.[89] As a result, Lloyd was summoned to perform some of her songs in front of a council committee.[94] She sang "Oh! Mr Porter" (composed for her by George Le Brunn), "A Little of What You Fancy"[3] and "She Sits Among the Cabbages and Peas",[95] which she retitled "I Sits Amongst the Cabbages and Leeks" after some protest.[96] The numbers were sung in such a way that the committee had no reason to find anything amiss. Feeling disgruntled at the council's interference, she then rendered Alfred Tennyson's drawing-room ballad "Come into the Garden, Maud" and displayed leers and nudges, to illustrate each innuendo. The committee were left stunned at the performance,[97] but Lloyd argued afterwards that the rudeness was "all in the mind".[3]

Despite their opposing views on music hall entertainment, Lloyd and Chant shared similar political views, and were wrongly assumed by the press to be enemies.[3][n 18] An inspector who reported on one of Lloyd's performances at the Oxford music hall thought that her lyrical content was fine but her knowing nods, looks, smiles and the suggestiveness in her winks to the audience suggested otherwise.[89] The restrictions imposed on the music halls were, by now beginning to affect trade, and many were threatened with closure.[98] To avoid social unrest, Hackney council scrapped the licensing restrictions on 7 October 1896.[99] In 1896, Lloyd sailed to South Africa with her daughter, who appeared as Little Maudie Courtenay on the same bill as her mother.[100] Lloyd came to the attention of Barney Barnato, a British entrepreneur who was responsible for mining diamond and gold. Barnato lavished gifts on her in an attempt to woo her, but his attempts were unsuccessful; nevertheless, the two remained friends until his death in 1897. The tour was a triumph for Lloyd, and her songs became popular among her South African audience. She performed "Wink the Other Eye", "Twiggy-Vous", "Hello, Hello, Hello",[101] "Whacky, Whacky, Whack!", "Keep Off the Grass",[102] and "Oh! Mr Porter". Feeling satisfied at the success she had achieved, Lloyd returned to London once the two-month tour had ended.[101]

The following year, Lloyd travelled to New York where she re-appeared at Koster and Bial's Music Hall. Her first song was about a young woman who lacked confidence in finding a suitor. The chorus, "Not for the very best man that ever got into a pair of trousers", proved hilarious; The Era observed that the line "tickled the audience immensely". Following this, she performed a song about a French maid who appeared innocent and petite at first sight, but turned out not to be so. The Era described the character as being "not so demure as she looked, for she confided to her auditors that she 'knew a lot about those tricky little things they don't teach a girl at school'." Many other songs followed and were all warmly received. At the conclusion of each performance, she received gifts from the audience including bouquets and floral structures.[103] The Era commented that "Miss Lloyd's clever character work, her versatility and unflagging endeavours to please were rewarded with deserved success".[103] After the tour, Lloyd returned to London, and moved to Hampstead with Hurley.[104] That Christmas, she appeared in pantomime, this time at the Crown Theatre in Peckham in a production of Dick Whittington in which she played the title role. In it, she sang "A Little Bit Off the Top", which MacQueen-Pope describes as being "one of the pantomime songs of the year". The Music Hall and Theatre Review was equally complimentary, saying: "Brilliant Repertory, Charming Dresses, A Unique Personality!"[105] During the Christmas period of 1898–9, Lloyd returned to the Crown where she took her benefit, during which she appeared in Dick Whittington. The entertainment culminated with a song from Vesta Victoria, and a short piece called The Squeaker, starring Joe Elvin.[106]

1900s

In February 1900, Lloyd was the subject of another benefit performance at the Crown Theatre in Peckham. Kate Carney, Vesta Tilley and Joe Elvin were among the star turns who performed before the main piece, Cinderella, which starred Lloyd, her sister Alice, Kittee Rayburn and Jennie Rubie.[107] The same year, although her divorce was not yet finalised, Lloyd went to live with Hurley in Southampton Row, London. Hurley, an established singer of coster songs, regularly appeared on the same bill as Lloyd; his calm nature was a contrast to the abusive personality of Courtenay.[108] Lloyd and Hurley set sail for a tour of Australia in 1901, opening at Harry Rickards Opera House in Melbourne on 18 May[109] with their own version of "The Lambeth Walk".[110][n 19] After the successful two-month tour, Lloyd and Hurley returned to London where she appeared in the only revue of her career. Entitled The Revue, it was written by Charles Raymond and Phillip Yorke with lyrics by Roland Carse and music by Maurice Jacobi. It was staged at the Tivoli theatre, in celebration of the Coronation of King Edward VII.[112] Lloyd and Courtenay's divorce became absolute on 22 May 1905, and she married Hurley on 27 October 1906.[113] Hurley, although ecstatic with his earlier success in Australia, began feeling sidelined by his wife's popularity. MacQueen-Pope suggested that "[Hurley] was a star who had married a planet. Already the seeds of disaster were being sown."[114][n 20]

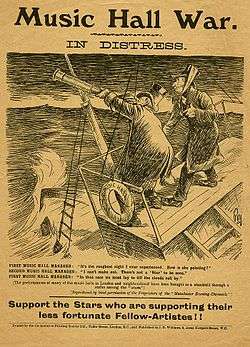

Music hall strikes of 1907

Shortly after her marriage to Hurley, Lloyd went to Bournemouth to recuperate from exhaustion. Within days she was back performing in London music halls.[115] From the start of the new century, music hall artistes and theatre managers had been in dispute over working conditions, a reduction in pay and perks, and an increased number of matinée performances. The first significant rift was a 1906 strike,[116] initiated by The Variety Artistes' Federation.[117] The following year, the Music Hall War commenced, which saw the Federation fight for more freedom and better working conditions on behalf of music-hall performers.[118] Although popular enough to command her own fees, Lloyd supported the strike,[119] acted as a picket for the strikers and gave generously to the strike fund.[120] To raise spirits, she often performed on picket lines and took part in a fundraising performance at the Scala Theatre. During one demonstration, she recognised someone trying to enter and shouted, "Let her through, girls, she'll close the music hall faster than we can." The singer was Belle Elmore, later murdered by her husband, Dr. Crippen. The dispute ended later the same year with a resolution broadly favourable to the performers.[121] In 1909, Lloyd appeared at the Gaiety Theatre in Dundee where a critic for The Courier noted "Her bright smile and fascinating presence has much to do with her popularity, while her songs are of the catchy style, perhaps not what a Dundee audience is familiar with, but still amusing and of an attractive style."[122]

Relationship with Bernard Dillon

Despite their marital problems, Lloyd went on an American tour with Hurley in 1908. She was eager to equal the success of her sister Alice, who had become popular in the country a few years previously.[121] By 1910, Marie's relationship with Hurley had ended, due in part to her endless parties and her developing friendship with the jockey Bernard Dillon, winner of the 1910 Derby.[3][123][n 21] Lloyd and the young sportsman began an open and passionate affair. For the first time, her private life eclipsed her professional career. She was seldom mentioned in the theatrical press in 1910, and when she did perform, it was not to the best of her abilities.[124] The writer Arnold Bennett, who witnessed her on stage at the Tivoli Theatre in 1909, admitted that he "couldn't see the legendary cleverness of the vulgarity of Marie Lloyd" and accused her songs of being "variations of the same theme of sexual naughtiness."[125] As with Courtenay years previously, the shy and retiring Dillon was finding it hard to adapt to Lloyd's elaborate and sociable lifestyle.[126] Dillon's success on the racecourse was short lived.[127] In 1911, he was expelled from the Jockey Club for borrowing £660 to bet on his own horses to win.[128] Dillon's horses lost, and he ended up in debt to trainers.[127] He became jealous of Lloyd's successful life in the spotlight.[129] Depression led to drink and obesity, and he started to abuse her.[130] Hurley, meanwhile, had initiated divorce proceedings, the strain of which caused him to drink heavily, which in turn finished his theatrical career.[131] Lloyd left the marital home in Hampstead and moved to Golders Green[132] with Dillon, a move which MacQueen-Pope describes as being "the worst thing she ever did."[133]

Later years

A new show in London in 1912 showcased the best of music hall's talent.[134] The Royal Command Performance took place at the Palace Theatre in London, which was managed by Alfred Butt.[135] The show was organised by Oswald Stoll, an Australian impresario who managed a string of West End and provincial theatres. Stoll, although a fan of Lloyd's, disliked the vulgarity of her act and championed a return to a more family-friendly atmosphere within the music hall.[136] Because of this, and her participation in the earlier music hall war, Stoll left her out of the line-up.[14] He placed an advert in The Era on the day of the performance warning that "Coarseness and vulgarity etc are not allowed ... this intimation is rendered necessary only by a few artists".[137] In retaliation, Lloyd staged her own show at the London Pavilion, advertising that "every one of her performances was a command performance by order of the British public".[3][138] She performed "One Thing Leads to Another", "Oh Mr Porter", and "The Boy I Love Is up in the Gallery" and was hailed as "the Queen of Comedy" by critics.[139] The same year, she travelled to Devon where she appeared at the Exeter Hippodrome to much success. The Devon and Exeter Gazette, reported that Lloyd's performance of "Every Movement Tells a Tale", was "thoroughly enjoyed" by the audience and "[received] round after round of applause". The paper also praised her recital of a "Cockney girl's honeymoon in Paris", which was met by "roars of laughter".[140]

Scandal in America

In 1913, Lloyd was booked by the Orpheum Syndicate to appear at the New York Palace Theatre. She and Dillon set sail on the RMS Olympic under the name Mr and Mrs Dillon[141] and were met at the American port by her sister Alice, who had resided in the country for many years.[142] Upon arrival, Lloyd and Dillon were refused entry when the authorities found out that they were not married, as they had claimed when applying for entry visas. They were detained and threatened with deportation on the grounds of moral turpitude[143] and were sent to Ellis Island while an enquiry took place.[144] Dillon was charged under the White Slave Act with attempting to take into the country a woman who was not his wife, and Lloyd was charged with being a passive agent.[3] After a lengthy enquiry, a surety of $300 each, and an imposed condition that they were to live apart while in America, the couple were allowed to stay until March 1914.[145] Alice later stated that "the indignity of the subsequent experience [while in custody] went to Marie's heart in a way she never survived. She could not bear to talk of that awful twenty-four hours."[146]

Despite the problems, the tour was a success, and Lloyd performed to packed theatres throughout America. Her act featured the songs "The Tiddly Wink", "I'd Like to Live in Paris All the Time (The Coster Girl in Paris)", and "The Aviator". The numbers were popular, partly due to the Americanisation of each song's lyrics.[147] On a personal level, Lloyd's time in America was miserable and was made worse by the increasing domestic abuse she received from Dillon. The assaults caused her to miss several key performances, which angered the theatre manager, Edward Albee, who threatened her with a breach of contract action. She claimed that illness made it difficult for her to perform and protested at her billing position.[148] The theatrical press were not convinced. The New York Telegraph speculated "In vaudeville circles her domestic relations are thought to be at the bottom of her attacks of disposition."[149] Back in England, Hurley had died of pleurisy and pneumonia on 6 December 1913.[150] Lloyd heard the news while appearing in Chicago and sent a wreath with a note saying "until we meet again".[151] She was reported in The Morning Telegraph as saying: "With all due respect to the dead, I can cheerfully say that's the best piece of news I've heard in many years, for it means that Bernard Dillon and I will marry as soon as this unlucky year ends."[152] Lloyd married Dillon on 21 February 1914, the ceremony taking place at the British Consulate in Portland, Oregon.[153] When the tour finished, Lloyd commented, "[I will] never forget the humiliation to which I have been subjected and I shall never sing in America again, no matter how high the salary offered."[154]

First World War and final years

Lloyd and Dillon returned to England in June 1914.[151] Lloyd started a provincial tour of Liverpool, Aldershot, Southend, Birmingham and Margate, and finished the summer season at the London Hippodrome.[155] She sang "The Coster Honeymoon in Paris" and "Who Paid the Rent for Mrs Rip Van Winkle?", the latter of which had been received particularly well with her American audiences. Within a fortnight, Britain was at war, which threw the music-hall world into disarray. The atmosphere in London's music halls had turned patriotic, and theatre proprietors often held charity events and benefits to help the war effort.[156] Lloyd played her part and frequently visited hospitals, including the Ulster Volunteer Force Hospital in Belfast,[157] where she interacted with wounded servicemen. She also toured munitions factories to help boost public morale,[158] but received no official recognition for her work.[159] During 1914, she scored a hit with "A Little of What you Fancy", which critics thought captured her life perfectly up until that point. The song is about a middle-aged woman who encourages the younger generation to enjoy themselves, rather than indulging in life's excitement herself. During the rendition, Lloyd depicts a young couple who cuddle and kiss on a railway carriage, while she sits back and recalls memories of her doing the same in years gone by.[160]

In January 1915, Lloyd appeared at the Crystal Palace where she entertained over ten thousand troops. At the end of that year, she performed her only war song, "Now You've Got your Khaki On", composed for her by Charles Collins and Fred W. Leigh, about a woman who found the army uniform sexy and thought that wearing it made the average pot-bellied gentleman look like a muscle-toned soldier. Lloyd's brother John appeared with her on stage dressed as a soldier and helped characterise the ditty. Following this, she sang the already well-established songs "If You Want to Get On in Revue", which depicted a young girl who offered sexual favours to promote her theatrical career, and "The Three Ages of Woman", which took a cynical look at men from a woman's perspective.[161] She seldom toured during the war, but briefly performed in Northampton, Watford and Nottingham in 1916. By the end of that year, she had suffered a nervous breakdown which she blamed on her hectic workload and a delayed reaction to Hurley's death.[162] During the war years, Lloyd's public image had deteriorated.[163] Her biographer Midge Gillies thought that Lloyd's violent relationship with Dillon and professional snubs in public had left the singer feeling like "someone's mother, rather than their sweetheart."[163]

In July 1916, Dillon was conscripted into the army, but disliked the discipline of regimental life. He applied for exemption on the grounds he had to look after his parents and four brothers,[164] but his claim was rejected. In a later failed attempt, he tried to convince army officials that he was too obese to carry out military duties.[165] On the rare occasions when Dillon was allowed home on leave, he would often indulge in drinking sessions. One night, Lloyd's friend Bella Burge received a knock at the front door to find a hysterical Lloyd covered in blood and bruises. When asked to explain what had caused her injuries, she stated that she had caught Dillon in bed with another woman and had had a showdown with her husband.[166] By 1917, Dillon's drinking had become worse. That June, two constables were called to Lloyd and Dillon's house in Golders Green after Dillon committed a drunken assault on his wife. Police entered the house and found Lloyd and her maid cowering beneath a table. Dillon confronted the constables and assaulted one of them, which resulted in him being taken to court, fined and sentenced to a month's hard labour.[167] Lloyd began drinking to escape the trauma of her domestic abuse. That year, she was earning £470 per week[168] performing in music halls and making special appearances. By 1918, she had become popular with the British-based American soldiers, but had failed to capture the spirits of their English counterparts,[163] and began feeling sidelined by her peers; Vesta Tilley had led a very successful recruitment drive into the services, and other music hall performers had been honoured by royalty.[157] The following year, she performed perhaps her best known song, "My Old Man (Said Follow the Van)", which was written for her by Fred W. Leigh and Charles Collins. The song depicts a mother fleeing her home to avoid the rent man.[169] The lyrics reflected the hardships of working class life in London at the beginning of the 20th century, and gave her the chance to costume the character in a worn out dress and black straw boater, while carrying a birdcage.[170]

In July 1919, Lloyd was again left off the cast list for the Royal Variety Performance, which paid tribute to the acts who helped raise money and boost morale during the war years. She was devastated at the snub and grew bitter towards her rivals who had been acknowledged. Her biographer Midge Gillies compared Lloyd to a "talented old aunt who must be allowed to have her turn at the piano even though all everyone really wants is jazz or go to the Picture Palace".[171] She toured Cardiff in 1919, and in 1920 she was earning £11,000 a year.[168] Despite the high earnings, she was living beyond her means, with a reckless tendency to spend money. She was famous for her generosity, but was unable to differentiate between those in need and those who simply exploited her kindness.[172][n 22] Her extravagant tastes, an accumulation of writs from disgruntled theatre managers, an inability to save money, and generous hand-outs to friends and family,[173] resulted in severe money troubles during the final years of her life.[168]

Decline and death

In 1920, Lloyd appeared twice at Hendon Magistrates Court and gave evidence of the abuse she had suffered from Dillon.[174] Soon afterwards, she separated from him and, as a result, became depressed.[3] When asked by prosecutors how many times Dillon had assaulted her since Christmas 1919, Lloyd replied "I cannot tell you, there were so many [occasions]. It has happened for years, time after time, always when he is drunk."[175] By now, she was becoming increasingly unreliable on stage; she appeared at a theatre in Cardiff for a mere six minutes before being carried off by stage hands. During the performance, she seemed dazed and confused, and she stumbled across the stage. She was conscious of her weak performances and frequently cried between shows. Virginia Woolf was among the audience at the Bedford Music Hall on 8 April 1921 and described Lloyd as "A mass of corruption – long front teeth – a crapulous way of saying 'desire', and yet a born artist – scarcely able to walk, waddling, aged, unblushing."[176]

In April 1922, Lloyd collapsed in her dressing room after singing "The Cosmopolitan Girl" at the Gateshead Empire in Cardiff. Her doctor diagnosed exhaustion, and she returned to the stage in August. Her voice became weak, and she reduced her act to a much shorter running time.[177] Her biographer Naomi Jacob thought that Lloyd was "growing old, and [she] was determined to show herself to her public as she really was ... an old, grey-faced, tired woman".[178] On 12 August 1921, Lloyd failed to show for an appearance at the London Palladium, choosing instead to stay at home and write her will.[176][n 23]

In early 1922, Lloyd moved in with her sister Daisy to save money.[179] On 4 October, against her doctor's advice,[177] she appeared at the Empire Music Hall in Edmonton, North London, where she sang "I'm One of the Ruins That Cromwell Knocked About a Bit". Her performance was weak, and she was unsteady on her feet, eventually falling over on stage. Her erratic and brief performance proved hilarious for the audience, who thought that it was all part of the act.[180] A week later, while appearing at the Alhambra Theatre, she was taken ill on stage and was found later in her dressing room crippled with pain, complaining of stomach cramps. She returned home later that evening, where she died of heart and kidney failure three days later, aged 52.[n 24] More than 50,000 people attended her funeral at Hampstead Cemetery on 12 October 1922.[182][183][n 25] Lloyd was penniless at the time of her death and her estate, which was worth £7,334,[184] helped to pay off debts that she and Dillon had incurred over the years.[185]

Writing in The Dial magazine the following month, T.S. Eliot claimed: "Among [the] small number of music-hall performers, whose names are familiar to what is called the lower class, Marie Lloyd had far the strongest hold on popular affection."[12] Her biographer and friend MacQueen-Pope thought that Lloyd was "going downhill of her own volition. The complaint was incurable, some might call it heartbreak, perhaps a less sentimental diagnosis is disillusionment."[186] The impersonator Charles Austin paid tribute by saying "I have lost an old pal, and the public has lost its principal stage favourite, one who can never be replaced."[187]

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ John "Brushie" Wood was of Irish descent; the son of a willow-cutter father and a willow-weaver mother, he grew up in the English countryside. Matilda Wood's parents were boot makers from London. John and Matilda married in Bethnal Green, London in April 1869.[2]

- ↑ Her siblings were John (b. 17 December 1871); Alice (b. 20 October 1873); Grace (b. 13 October 1875); Daisy (b. 15 September 1877); Rosie (b. 5 June 1879); Annie (b. 25 June 1883); Sydney (b. 1 April 1885); and Maud (b. 25 September 1890). John, Grace and Annie were the only children who did not become performers.[5][6] Two, Percy and May, died in infancy, the former from mumps and the latter by accidental suffocation.[4]

- ↑ In 1880, the act featured Lloyd's brother Johnny (age 9), and sisters Alice (7), Grace (5), Daisy (3), and Anne (18 months).[11]

- ↑ In one sketch, Lloyd dressed in clothes borrowed from her father and played the part of an alcoholic husband, who arrives home late in a drunken state. Alice played the wife who complained of her husband's debauchery and alcoholic ways. Marie then sang the song "Throw Down the Bottle and Never Drink Again", after vowing to his wife that he was to give up alcohol for good.[11]

- ↑ This stage name was spelled differently by various biographers, including Bella Delmare (by Naomi Jacob); Belle Delamere (by W. J. MacQueen-Pope in The Melodies Linger On and Bella Delmore in Queen of the Music Halls); and Bella Delmere (by M.W. Disher and Colin Macinnes). Lloyd's biographer Daniel Farson chooses the latter spelling calling Disher "the most accurate authority".[16]

- ↑ Other performers on the bill included the Sergeant Simms Zouave Troupe, the King of Egypt, a one-legged champion, and others.[25]

- ↑ "Oh Jeremiah, Don't you Go to Sea", was written in 1889 by Tom Maguire. Maguire was blind and dictated the song's lyrics to his 10-year-old daughter, who wrote them down. The songs were later published by Sheard & Co and T.B. Harms & Francis, Day & Hunter, Inc.[32]

- ↑ On the marriage certificate, Courtenay gave his profession as a captain in the British army. Lloyd gave her age as 18 (although she was 17 at the time), and left a blank space next to her job, as a music hall performer was looked upon as being a lewd and scandalous profession.[37]

- ↑ Marie Jr. was born at 55 Graham Road, Hackney, on 19 May 1888. For the purposes of the birth certificate, Courtenay was shown as a "commission agent" while Lloyd's occupation was omitted.[38] Marie Jr. later became a performer and took the stage name "Marie Lloyd Jr". She performed in music halls for many years, and starred in a few films in the 1930s. She lived until the age of 79 and was buried with her mother in 1967.[39]

- ↑ Burge was an actress who used the stage name Bella Lloyd. She appeared on the same bill as Lloyd's sisters Alice and Grace, who were starring in a Christmas pantomime at the Pavilion Theatre, Whitechapel in 1889. Alice and Grace were appearing as the Sisters Lloyd.[40]

- ↑ Walter Macqueen-Pope called Lloyd a Principal Girl and noted that "There is often a misconception about this and a belief that she was Principal Boy there. She was Principal Boy in other pantomimes but never at Drury Lane."[50]

- ↑ Most pantomimes in the 18th and 19th centuries ended in the harlequinade which was featured as an after-piece to the main performance. The harlequinade became the larger part of the entertainment, and the transformation scene was presented with spectacular stage effects.[64]

- ↑ The A.B.C Girl was written by Henry Chance Newton and centred around a "girl about town" who was learning the facts of life. The tour visited Dublin, Nottingham, Stratford, and Sheffield, but was unsuccessful. Its demise was blamed on Lloyd's inability to act.[71]

- ↑ The inscription on the service read: "Marie Lloyd from Koster and Bial, Friday 12 December 1890, New York." A contract for a future engagement was placed inside the tea pot.[73]

- ↑ Despite the audience's obvious joy, Lloyd grew insecure of her French performances. A stage hand found the actress crying in her dressing room after a performance and comforted her. Lloyd confided "I done my best and they call me a beast". The friend gently pointed out that what the audience were actually shouting was "Bis, Bis" (French for "more").[78]

- ↑ After the incident, Lloyd and Burge travelled by horse and brougham to seek refuge at the Prince's tavern in Wardour Street, which Lloyd had bought her family a few years before. When they arrived, Courtenay was again waiting by the rear door. Courtenay shouted "I am going to murder you tonight. I will shoot you stone dead and you will never go on stage any more." Lloyd's uncle restrained Courtenay, and the couple fled once more.[83]

- ↑ Hurley was born in 1871 in Hackney and was the son of an Irish Sea captain. After appearing briefly in a double act with his brother, Hurley became a coster comedian and was likened to Albert Chevalier. Lloyd may have met Hurley as early as 1892.[85]

- ↑ Chant's pressure for censorship was based on the Contagious Diseases Act, which prevented the spread of venereal infection by allowing the police to arrest prostitutes and force them to undergo a medical examination. Chant was also a campaigner against domestic violence, something that Lloyd experienced in all of her marriages.[3]

- ↑ The song was Hurley's version of the Cakewalk, a popular dance craze at the time. "The Lambeth Walk" was not connected to the later Noel Gay hit.[110][111]

- ↑ MacQueen-Pope wrongly assumed that the couple were married by 1901.[114]

- ↑ Dillon was born in 1888 in Tralee, Ireland and moved to England at age thirteen, where he took up horse racing. Dillon met Lloyd at one of her parties in 1910, having been invited by Marie Jr.[123]

- ↑ A family legend has it that one day Lloyd was met by a man who asked for an advance in order to help him with his new invention. She thought the request sounded too elaborate so declined to help, causing Guglielmo Marconi to look elsewhere. Stories of her spending included hiring an East End hotel so she could provide 150 beds for the area's homeless children; buying her family a hotel in Hastings and a pub in Soho;[172] and buying two house boats on the Thames called Moonbeam and Sunbeam.[104]

- ↑ Lloyd left her brother John £300 and her maid £100. The rest was split between Lloyd's daughter and a group of Hoxton charities.[176]

- ↑ Lloyds death certificate diagnosed "Nitral Regurgitation – 14 months; Nephritis (an inflammation of the kidneys) – 14 months; and Uraemic Coma – 3 days."[181]

- ↑ Six hearses were used to carry the flowers during the funeral procession.[182]

References

- ↑ Gillies, p. 19

- ↑ Gillies, p. 5

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Gray, Frances. "Lloyd, Marie", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, accessed 2 Dec 2012 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- 1 2 Gillies, p. 7

- ↑ Farson, p. 73

- ↑ Pope, p. 97

- ↑ A description given in Pope, p. 23

- ↑ Gillies, p. 8

- ↑ Pope, p. 25

- ↑ Farson, p. 35

- 1 2 3 4 Farson, p. 36

- 1 2 A letter by T. S. Eliot to The Dial Magazine, 4 December 1922, pp. 659–663, quoted in Rainey, p.164

- 1 2 "Lloyd, Edward", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, accessed 3 December 2012 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- 1 2 3 "Biography of Marie Lloyd", Victoria and Albert Museum website, accessed 30 December 2012

- ↑ Gillies, p. 9

- 1 2 3 Farson, p. 37

- ↑ Gillies, p. 11

- 1 2 Gillies, p. 16

- ↑ Gillies, p. 17

- 1 2 3 Gillies, p. 18

- ↑ Pope, p. 30

- ↑ Pope, pp. 36–37

- ↑ Gillies, pp. 21–22

- ↑ Pope, p. 37

- 1 2 3 4 Farson, p. 38

- ↑ Pope, p. 39

- 1 2 3 "A Chat With Marie Lloyd", The Era, 28 October 1893, p. 16

- ↑ "Sebright Music Hall, Hackney", Over the Footlights.co.uk, accessed 28 February 2013

- ↑ As quoted in Farson, p. 39

- ↑ Farson, p. 39

- ↑ Pope, p. 40

- ↑ "Blind But Not Old", The Era, 4 November 1893, p. 16

- ↑ Pope, p. 50

- ↑ Farson, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Pope, p. 73

- ↑ Pope, p. 56

- ↑ Farson, p. 40

- ↑ Gillies, p. 36

- ↑ Marie Lloyd Jr. filmography, British Film Institute, accessed 4 December 2012

- ↑ Farson, p. 41

- ↑ Pope, p. 60

- 1 2 3 "Marie Lloyd Divorced", The Western Times, 5 November 1904, p. 6

- ↑ Gillies, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Gillies, p. 40

- ↑ Gillies, p. 41

- 1 2 3 Pope, pp. 68–69

- ↑ Sheet music - Then You Wink The Other Eye, Victoria and Albert Museum website, accessed 26 March 2013

- ↑ Pope, p. 72

- ↑ Gillies, pp. 129–130

- ↑ MacQueen-Pope, p. 82

- 1 2 3 Gillies, p. 53

- 1 2 3 Farson, p. 45

- ↑ Pope, pp. 85–86

- 1 2 Farson, p. 46

- ↑ "Humpty Dumpty", The Times, 28 December 1891, p. 8

- ↑ Gillies, p. 55

- ↑ "Humpty Dumpty Triumph", London Entr'acte, 2 January 1892, p. 2

- ↑ Compton Mackenzie's memoirs, p. 232, as quoted in Gillies, p. 56

- ↑ Gillies, p. 58

- ↑ "Miss Marie Lloyd at the Oxford", The Era, 12 September 1891, p. 3

- ↑ Gillies, p. 60

- ↑ Pope, p. 87

- ↑ Gillies, p. 74

- ↑ Hartnoll, Phyllis and Peter Found (eds). "Harlequinade", The Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre, Oxford Reference Online, Oxford University Press, 1996, accessed 10 April 2013 (subscription required)

- ↑ "1892: Hop O' My Thumb" Its-behind-you.com, accessed 2 February 2013

- ↑ Farson, pp. 45–46

- ↑ Letters to Reggie as quoted in Gillies, p. 76

- ↑ The Times, 1 April 1892, p. 2

- ↑ Anthony, p. 115

- ↑ Pope, pp. 114–115

- ↑ Gillies, p. 126

- ↑ Gillies, pp. 46–47

- ↑ Gillies, p. 47

- ↑ "Success in New York", London Entr'acte, 23 May 1893, p. 2

- ↑ Gillies, pp. 47–48

- ↑ Farson, pp. 46–47

- ↑ Farson, p. 47

- ↑ Farson, p. 48

- ↑ Pantomimes at Drury Lane, Its-behind-you.com, accessed 18 March 2013

- ↑ Pope, p. 88

- ↑ Gillies, p. 83

- 1 2 Farson, pp. 42–43

- ↑ Farson, p. 43

- ↑ Gillies, p. 85

- ↑ Gillies, pp. 122–123

- ↑ Liverpool Review, 29 December 1894, as quoted in Gillies, p. 95

- ↑ Pope, p. 138

- ↑ Farson, p. 64

- 1 2 3 "Sources for the history of London Theatres and Music Halls at London Metropolitan Archives", London Metropolitan Archives, Information Leaflet Number 47, pp. 4–5, accessed 11 April 2013

- ↑ Gillies, p. 315

- ↑ Gillies, p. 89

- ↑ Gillies, p. 101

- ↑ Gillies, p. 102

- ↑ Pope, p. 140

- ↑ Nuttall, Carmichael, p. 34

- ↑ "The BBC should see the funny side of risqué humour", The Telegraph (online edition), accessed 8 April 2013

- ↑ Pope, p. 141

- ↑ Farson, pp. 64–65

- ↑ Farson, p. 69

- ↑ Pope, p. 95

- 1 2 Farson, p. 77

- ↑ Pope, p. 93

- 1 2 "Marie Lloyd In New York", The Era, 23 October 1897, p. 18

- 1 2 Gillies, p. 124

- ↑ Pope, pp. 89–90

- ↑ "Miss Marie Lloyd's Benefit", The Era, 25 February 1899, p. 19

- ↑ "Marie Lloyd's Benefit", The Era, 17 February 1900, p. 18

- ↑ Farson, p. 79

- ↑ Pope, p. 120

- 1 2 Farson, p. 80

- ↑ Pope, p. 119

- ↑ Pope, p. 110

- ↑ Farson, p. 82

- 1 2 Farson, p. 81

- ↑ Gillies, p. 170

- ↑ Pope, p. 131

- ↑ Gillies, p. 171

- ↑ Pope, pp. 131–132

- ↑ Farson, p. 83

- ↑ Pope, p. 132

- 1 2 Pope, p. 133

- ↑ "Marie Lloyd at the Gaiety", The Courier, 30 March 1909, p. 7

- 1 2 Farson, p. 85

- ↑ Gillies, p. 216

- ↑ Bennett, p. 356

- ↑ Gillies, p. 222

- 1 2 Gillies, pp. 232–233

- ↑ "Mr Dillon's debt", The Times, 6 June 1913, p. 5

- ↑ Gillies, p. 233

- ↑ Farson, p. 87

- ↑ Farson, pp. 86–87

- ↑ "A Jockey Divorced", The Advertiser, 19 December 1913, p. 11

- ↑ Pope, p. 151

- ↑ Pope, p. 143

- ↑ Farson, p. 93

- ↑ Farson, pp. 88–89

- ↑ The Era as quoted in Jacob, p. 93

- ↑ Pope, pp. 148–149

- ↑ Farson, p. 96

- ↑ "Marie Lloyd At Exeter Hippodrome", The Devon and Exeter Gazette, 27 August 1912, p. 10

- ↑ Farson, p. 98

- ↑ "Miss Marie Lloyd Is Ordered to Be Deported From America", The Courier, 3 October 1913, p. 5

- ↑ Farson, p. 99

- ↑ "The Detention of Miss Marie Lloyd and Dillon", Derby Daily Telegraph, 4 October 1913, p. 5

- ↑ Farson, p. 101

- ↑ "My sister Marie Lloyd", Lloyds Sunday News, 10 December 1922, p. 4

- ↑ Gillies, p. 242

- ↑ Gillies, p. 243

- ↑ New York Telegraph, 26 November 1913; as quoted in Gillies, p. 243

- ↑ Farson, p. 102

- 1 2 Farson, p. 103

- ↑ The Morning Telegraph, 1913 (full date not given); as quoted in Gillies, p. 245

- ↑ "Marie Lloyd Married", Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advisor, 23 February 1914, p. 7

- ↑ The New York Sun, 4 October 1913, p. 3; as quoted in Gillies, p. 240

- ↑ Gillies, p. 249

- ↑ Farson, pp. 103–104

- 1 2 Gillies, p. 256

- ↑ Farson, p. 104

- ↑ Farson, p. 105

- ↑ Gillies, pp. 257–258

- ↑ Gillies, p. 252

- ↑ Gillies, pp. 254–255

- 1 2 3 Gillies, p. 257

- ↑ The Times, 29 July 1916, p. 18

- ↑ Gillies, pp. 255–256

- ↑ Farson, p. 106

- ↑ "Marie Lloyd's Husband Gets Months Hard Labour for Assault on Police", The Evening Telegraph and Post, 7 June 1917, p. 2

- 1 2 3 Farson, p. 116

- ↑ Gillies, pp. 261–262

- ↑ Farson, p. 54

- ↑ Gillies, p. 265

- 1 2 Gillies, p. 81

- ↑ Farson, pp. 116–117

- ↑ Gillies, p. 268

- ↑ Farson, p. 113

- 1 2 3 Gillies, p. 271

- 1 2 Farson, p. 118

- ↑ Jacob, p. 199

- ↑ Gillies, p. 272

- ↑ Farson, pp. 119–120

- ↑ Farson, p. 121

- 1 2 "50,000 Mourn as Marie Lloyd is Buried", The New York Times, 13 October 1922, p. 16

- ↑ "Marie Lloyd Buried", The Western Times, 13 October 1922, p. 12

- ↑ "What Marie Lloyd Left", Evening Telegraph, 8 November 1922, p. 7

- ↑ "The Death of Marie Lloyd", The Guardian (Archive), 22 October 1922

- ↑ Pope, p. 166

- ↑ "Miss Marie Lloyd", The Sunday Post, 8 October 1922, p. 1

Sources

- Bennett, Arnold (1976). Journal of Arnold Bennett: 1896–1910. London: Ayer Co Publishers. ISBN 978-0-518-19118-6.

- Farson, Daniel (1972). Marie Lloyd and Music Hall. London: Tom Stacey Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85468-082-5.

- Gillies, Midge (1999). Marie Lloyd: The One And Only. London: Orion BooksLtd. ISBN 978-0-7528-4363-6.

- Jacob, Naomi (1972). Our Marie, Marie Lloyd: A Biography. London: Chivers Press. ISBN 978-0-85594-721-7.

- Mackenzie, Compton (1963). My Life and Times: Octave 1. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-0933-2.

- Macqueen-Pope, Walter (2010). Queen of the Music Halls: Being the Dramatized Story of Marie Lloyd. London: Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1-171-60562-1.

- Nuttall, Jeff; Carmichael, Rodick (1977). Common Factors-Vulgar Factions. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7100-8592-4.

- Rainey, Lawrence. S (2006). The Annotated Waste Land with Eliot's Contemporary Prose. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11994-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marie Lloyd. |

- Songs from Marie Lloyd, at the Internet Archive.

- "From the archive: The death of Marie Lloyd", The Guardian (online).

- Images of Marie Lloyd at the National Portrait Gallery.

- Marie Lloyd biography at the Victoria & Albert Museum.

- Queen of the Music Halls by W. J. MacQueen-Pope at the Internet Archive.