Mary Draper Ingles

| Mary Draper Ingles | |

|---|---|

| Born |

1732 Philadelphia |

| Died | 1 February 1815 (aged 82–83) |

| Known for | Escape from Indian captivity in 1755 |

| Parent(s) | George and Elenor (Hardin) Draper |

Mary Draper Ingles (1732 – February 1815), also known in records as Mary Inglis or Mary English, was an American pioneer and early settler of western Virginia. In the summer of 1755 she and her two young sons were among several captives taken by Shawnee after the Draper's Meadow Massacre during the French and Indian War. They were taken to Lower Shawneetown at the Ohio and Scioto rivers. Ingles escaped with another woman after two and a half months, making a trek of 500–600 miles through the frontier, crossing numerous rivers and creeks, and over the Appalachian Mountains to return home.

Biography

Early life

Mary Draper Ingles was born in 1732 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to George and Elenor (Hardin) Draper, who had immigrated to America from Donegal, Ireland in 1729.[1] In 1748, the Draper family and others moved to the western frontier of Virginia, establishing Draper's Meadow, a pioneer settlement on the banks of Stroubles Creek near modern-day Blacksburg.

In 1750 Mary married fellow settler William Ingles (1729-1782). They had two sons together: Thomas, born in 1751, and George in 1753.[2][Note 1]

Draper's Meadow massacre

On July 30 (or July 8, according to one source[3]), 1755, during the French and Indian War, a band of Shawnee warriors (then allies of the French) raided Draper's Meadow, killing four settlers, including Mary's mother and her niece.[4][5] They took six captives, including Mary and her two sons, her sister-in-law Bettie Robertson Draper, and neighbors James Cull and Henry Lenard (or Leonard).[6][7][8] Mary's husband was nearly killed but fled into the forest.[2][9]

Captivity

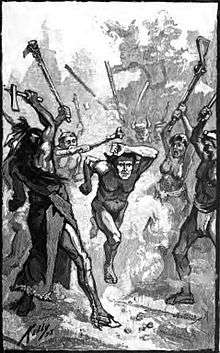

The Indians and their captives traveled for a month to Lower Shawneetown, located at the confluence of the Scioto and Ohio rivers. The Shawnee killed James Cull and Henry Leonard during the ritual of running the gauntlet. Mary was separated from her sons,[10] who were adopted by Shawnee families.

Some sources suggest that Mary gave birth to a daughter while in captivity[3][11][12] although there is evidence to the contrary.[6] As a prisoner, Mary sewed shirts using cloth traded to the Indians by French traders, and was paid in goods for her work.[2] In October 1755 she was taken to the Big Bone salt lick to make salt for the Indians by boiling brine.[8]

Escape and journey home

While working at Big Bone Lick, in late October 1755, Mary persuaded another captive woman, referred to as the "old Dutch woman" but who may have been German,[Note 2] to escape with her. The next day (probably 19 October) they set off, retracing the route that the Indians had followed after Mary was taken captive in July.[13] They wore moccasins and carried only a tomahawk and a knife (both of which were eventually lost), and two blankets. As they were leaving the camp, they met three French traders from Detroit who were harvesting walnuts. Mary traded her old dull tomahawk for a new one.[2]

They went north, following the Ohio River as it curves to the east (see map). Expecting pursuit, they tried to hurry at first.[14] As it turned out, the Shawnee made only a brief search, assuming that the two women had been carried off by wild animals. The Shawnee told this account to Mary's son Thomas Ingles when he met some of them many years later after the Battle of Point Pleasant (1774).[2]

After four or five days the women reached the junction of the Ohio with the Licking River, near the present-day location of Cincinnati. There they found an abandoned cabin, which contained a supply of corn, and an old horse in the back yard. They took the horse to carry the corn, but he was lost in the river when they tried to take him across what was probably Dutchman's Ripple.[2]

They followed the Ohio, Kanawha, and New rivers, crossing the Licking, Big Sandy, Little Sandy rivers, Twelvepole Creek, the Guyandotte and Coal rivers, Paint Creek, and the Bluestone River.[15] During their journey, they crossed at least 145 creeks and rivers—remarkable as neither woman could swim. On at least one occasion they "tied logs together with a grape-vine [and] made a raft" to cross a major river.[3] They may have traveled as much as five to six hundred miles, averaging between eleven and twenty-one miles a day.[14]

Once the corn ran out, they subsisted on black walnuts, wild grapes, pawpaws,[14] Sassafras leaves, blackberries and frogs but, as the weather grew cold, they were forced to eat dead animals that they found along the way.[3] On several occasions they saw Indians hunting, and each time managed to avoid being seen.[16]

At some point during the journey, the old Dutch woman became "very disheartened and discouraged" and tried to kill Mary.[2] (Letitia Preston Floyd's account states that the two women drew lots to decide "which of them was to be eaten by the other."[3]) Mary managed to "keep her in a good humor", and soon afterward they reached the mouth of the Kanawha River. But, shortly after they reached the New River, the old Dutch woman made a second attempt on Mary's life, probably on 26 November.[14]

.jpg)

By now the temperature had dropped, it was starting to snow, and the two women were weak from starvation. Mary feared that the old Dutch woman would kill her in her sleep, so one night she went off alone and, finding a canoe, crossed the New River at its junction with the East River near what is now Glen Lyn, Virginia.[11] Mary continued southeast along the riverbank, passing through the present-day location of Pembroke. She reached the home of her friend Adam Harmon on or about 1 December 1755, forty-two days after leaving Big Bone salt lick. A search party went back and found the old Dutch woman shortly afterward.[2] Adam Harmon took her to the fort at Dunkard Creek, where she joined a wagon party traveling to Pennsylvania.[11]

Aftermath

After recovering from her journey and reuniting with her husband, Mary had four more children: Mary, Susan, Rhoda (b.1762), and John (1766-1836).[17][18] In 1762 William and Mary established the Ingles Ferry across the New River, and the associated Ingles Ferry Hill Tavern and blacksmith shop.[19] She died there in 1815 at the age of 83.[14] The site of her former log cabin, with a stable and a family cemetery, is protected as part of the Ingles Bottom Archeological Sites.

Mary's son George died in Indian captivity, but Thomas, who was four when taken captive, was ransomed and returned to Virginia in 1768 at the age of seventeen; after 13 years with the Shawnee, he had become fully acculturated and spoke only Shawnee. He underwent several years of "rehabilitation" and education under Dr. Thomas Walker at Castle Hill, Virginia.[20]

Thomas Ingles later served as a lieutenant under Colonel William Christian in Lord Dunmore's War (1773-1774) against the Shawnee. He married Eleanore Grills in 1775 and settled in Burke's Garden, Virginia. In 1782 his wife and three children were kidnapped by Indians. Thomas came to rescue them and in the ensuing altercation, the two older children were killed. Eleanore was tomahawked but survived.[10] The youngest daughter was rescued by her father.[21]

In 1761 Mary Ingles' brother John Draper attended a gathering of Cherokee chiefs at which a treaty to end the Anglo-Cherokee War was prepared. He found a man who knew of his wife, Bettie Robertson Draper, who had been taken captive in 1755. At that time, she was living with the family of a widowed Cherokee chief.[20] She was ransomed and John took her to New River Valley.[22]

Historical accounts of Mary Draper Ingles' journey

The two primary sources of information are:

- 1) the 1824 written account by John Ingles[2] (son of Mary and William Ingles, born after Mary's return);

- 2) parts of an 1843 letter by Letitia Preston Floyd[3] (wife of Virginia Governor John Floyd and daughter of Colonel William Preston, a survivor of the Draper's Meadow massacre).

Differences between the two narratives suggest that the Ingles and Preston families had developed distinct oral traditions. They differ on the date of the massacre (July 30 vs July 8, according to Ingles and Floyd, respectively), the number of casualties, the age of Mary Ingles' children, and several other aspects.[6]

John Peter Hale, one of Mary Ingles' great-grandsons, claimed to have interviewed Letitia Floyd and others who knew Mary Ingles personally. His 1886 narrative contains numerous details not cited in any previous account.[11] There were some references to Mary Ingles' escape in contemporary reports and letters, which were gathered in later efforts to document people who had been taken captive by Indians.[4][16]

In popular culture

The story of Ingles' ordeal has inspired a number of books and films; these include the following:

- The novel, Follow the River (1981) by James Alexander Thom.

- The ABC television movie (1995) of the same name starring Sheryl Lee.

- The Captives (2004), based on these events.

From 1971 to 1999, an outdoor historical drama, called The Long Way Home, was produced each summer at the Ingles homestead, relating the history of Mary Draper Ingles and her family. It was identified as the "official" outdoor drama by the General Assembly. While it attracted thousands to the city, the production was finally closed. Since 2010, other efforts have occurred to develop aspects of tourism heritage related to the Ingles history.[23]

Memorialization

- Radford University, located near Draper's Meadow, has residence halls named Draper Hall and Ingles Hall in honor of Mary Draper Ingles.[24]

- A monument dedicated to Mary Draper Ingles is located in West End Cemetery, Radford, Virginia. It was built using stones from the chimney of a home where Ingles lived after her return in 1755.

- Mary Ingles Elementary School in Tad, West Virginia is named for her.

- An 8-foot-tall (2.4 m) bronze statue depicting Mary Draper Ingles was installed outside the Boone County Public Library on route 18 in Burlington, Kentucky.

- Kentucky Route 8 in Campbell, Bracken, and Mason counties is officially named "Mary Ingles Highway."

- Ingles Ferry was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1969, and the Ingles Bottom Archeological Sites in 1978.[25]

- The Virginia Tech library holds documents once owned by Mary Draper Ingles.

- The Mary Draper Ingles Bridge crosses the New River and is located in Summers County, West Virginia.[26]

Notes

- ↑ In 1824, John Ingles, who heard the story from his mother Mary, wrote The Story of Mary Draper Ingles and Son Thomas Ingles. The original manuscript is at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collection in the University of Virginia library. It is very difficult to read, with little punctuation and poor spelling. It has been reproduced in an edition by Roberta Ingles Steele which retains the eccentricities of the author; copies are available at the Radford Public Library. This is probably the most significant primary document.

- ↑ Jennings (1968) identifies her as a "Mrs. Bingamin", wife of Henry Bingamin, both German immigrants. In his book History of Tazewell County and Southwest Virginia: 1748-1920 (1920) William Cecil Pendleton states that her name was "Frau Stump" and that she had been kidnapped from a settlement near Fort Duquesne. Ed Robey ("Who was the Old Dutch Woman?") believes that she was the wife of "Dutch Jacob," and was kidnapped during an attack on a New River community on 3 July, 1755.

References

- ↑ "About the Ingles Family", Virginia History Exchange

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Transcript of John Ingles' manuscript: "The Narrative of Col. John Ingles Relating to Mary Ingles and the Escape from Big Bone Lick," 1824.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Letitia Preston Floyd, "Memoirs of Letitia Preston Floyd, written Feb. 22, 1843 to her son Benjamin Rush Floyd".

- 1 2 "A Register of the Persons Who Have Been Either Killed, Wounded, or Taken Prisoners by the Enemy, in Augusta County, as also such as Have Made Their Escape," in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. II, June 1895, published by the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia.

- ↑ James Duvall,"The Context of Captivity: Mary Ingles at Big Bone Lick," paper presented at Northern Kentucky History Day, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Ellen Apperson Brown, "What Really Happened at Drapers Meadows? The Evolution of a Frontier Legend," Virginia History Exchange website.

- ↑ Kathy Cummings, "Walking in Their Footsteps: The Journey of Mary Ingles," Pioneer Times website.

- 1 2 Gary Jennings, "An Indian Captivity", American Heritage Magazine, August 1968, Vol. 19, Issue 5.

- ↑ William Cecil Pendleton, History of Tazewell County and Southwest Virginia: 1748-1920, W. C. Hill Printing Company, 1920, p. 270

- 1 2 John Lewis Peyton, History of Augusta County, Virginia, Samuel M. Yost & son, 1882, pp. 212-14.

- 1 2 3 4 John Peter Hale (1824-1902), Encyclopedia of West Virginia

- ↑ Thomas D. Davis, "Pioneer physicians of Western Pennsylvania: the president's address of the Medical Society of the State of Pennsylvania" Pennsylvania, 1901; pp. 20-21.

- ↑ E. M. Lahr and James Alexander Thom, Angels along the River: Retracing the Escape Route of Mary Draper Ingles, Bloomington, Ind.: AuthorHouse, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 James Duvall, "Mary Ingles and the Escape from Big Bone Lick" Boone County Public Library, 2009

- ↑ "Mary Draper Ingles map", History and Culture, National Park Service).

- 1 2 Contemporary newspaper account of Mary Ingles' escape, New York Mercury, 26 Jan 1756, p. 3 col. 1

- ↑ John Ingles

- ↑ "Mary Draper Ingles" entry in The Kentucky Encyclopedia.

- ↑ "Historic Ingles Ferry and Farm Permanently Protected", Virginia Outdoors Foundation, August 2009

- 1 2 Luther F. Addington, "Captivity of Mary Draper Ingles," Historical "Sketches of Southwest Virginia, Southwest Virginia Historical Society, Publication No 2, 1967.

- ↑ "Data for a Memoir of Thomas Ingles of Augusta Kentucky, 1854 by Thomas Ingles Jr.". Manuscript held at the Boone County Public Library.

- ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution Magazine, Volume 106, University of Michigan, 1972; p. 230.

- ↑ Heather Bell, "Reviving the Long Way Home: City holds public forum to discuss new historic drama", Radford News Journal, 25 November 2011

- ↑ Radford University map

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Mary Draper Ingles Bridge in Summers County WV

External links

- Mary Draper Ingles, History and Culture, National Park Service website.

- Mary Draper Ingles Trail Blazers website, an effort to recreate the route taken by Mary Ingles.

- Mary Draper Ingles' Return To Virginia's New River Valley, Blue Ridge Country website

- "Mary Draper Ingles", Boone County Public Library

- John Ingles, "The Narrative of Col. John Ingles Relating to Mary Ingles and the Escape from Big Bone Lick," 1824, Transcribed and edited for clarity by James Duvall, 2008, Boone County Public Library, Burlington, KY

- Scanned pages of the original John Ingles manuscript.

- "Memoirs of Letitia Preston Floyd, written Feb. 22, 1843 to her son Benjamin Rush Floyd", a primary source differing from John Ingles' account.

- Mary Ingles and the Escape from Big Bone Lick, A detailed examination of Mary Ingles' story, with illustrations.

- A map of northern Kentucky in 1796, showing "Bigbone Creek", the site of Mary Ingles' escape, and the Ohio River along which she traveled during the first half of her journey.