Monks Risborough

| Monks Risborough | |

Monks Risborough |

|

| OS grid reference | SP8004 |

|---|---|

| Civil parish | Princes Risborough |

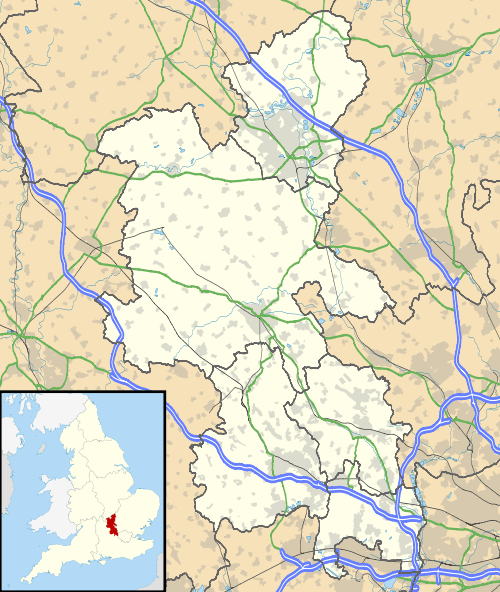

| District | Wycombe |

| Shire county | Buckinghamshire |

| Region | South East |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Princes Risborough |

| Postcode district | HP27 |

| Dialling code | 01844 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Buckinghamshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| EU Parliament | South East England |

| UK Parliament | Buckingham |

|

|

Coordinates: 51°44′04″N 0°49′47″W / 51.734462°N 0.829831°W

Monks Risborough is a village and ecclesiastical parish in Buckinghamshire, England, lying between Princes Risborough (where the 2011 Census population was included) and Great Kimble. The village lies at the foot of the northern scarp of the Chiltern Hills. It is 8 miles (13 km) south of the county town of Aylesbury and 9.5 miles (15.3 km) north of High Wycombe, on the A4010 road.

Until 1934 Monks Risborough was also a separate civil parish, but it now forms part of the much enlarged civil parish of Princes Risborough, with the exception of Meadle and Owlswick, which are both now in the civil parish of Longwick-cum-Ilmer.

The boundaries of the ecclesiastical parish of Monks Risborough are almost the same as the former Manor of Monks Risborough and of the original estate laid out in the 8th or 9th century. References to the 'parish' are therefore to the area covered by the ecclesiastical parish unless otherwise stated.[1]

The ecclesiastical parish of Monks Risborough includes the hamlets of Meadle, Owlswick, Askett, Cadsden and Whiteleaf.

Description

The parish is long and narrow. It is almost six miles (10 km) in length, from Owlswick in the north to Monkton Farm on the outskirts of Speen in the south; but it is only one and a quarter miles wide at the widest part (at Meadle) and barely four hundred yards at the narrowest parts (at Green Hailey and in Monkton Wood). Like the neighbouring Chiltern 'strip parishes' the estate was originally laid out so as to include different types of land, fertile land below the scarp of the Chiltern Hills, a section of the scarp itself and grazing or woods above it.

At the foot of the scarp, where there are springs, is the village of Monks Risborough, with the church, and also Askett and Cadsden, nearer to Aylesbury on either side of the main road. Meadle and Owlswick lie further north. Whiteleaf is halfway up the slope on the south side of the Aylesbury Road and the parish continues further to the south above the scarp along the high land through Green Hailey to Redland End and Monkton Wood and Farm.

Approximate heights above sea level are 85 m (279 ft) at Meadle and Owlswick, 100 m (328 ft) by the Church, 247 m (810 ft) at Green Hailey, where there is a water tower, and 200 m (656 ft) at Monkton Farm near Speen.[2]

Monks Risborough looking north from near the top of Whiteleaf Hill (The white line shows very approximately the western boundary with Princes Risborough beyond)

Monks Risborough looking north from near the top of Whiteleaf Hill (The white line shows very approximately the western boundary with Princes Risborough beyond) Path in Monkton Wood looking south near the southern limit of the parish. (The field on the right is in Princes Risborough).

Path in Monkton Wood looking south near the southern limit of the parish. (The field on the right is in Princes Risborough). The village seen from the main road (A4010) in 2009.

The village seen from the main road (A4010) in 2009.

The name

The name 'Risborough' meant 'brushwood-covered hills' and comes from two Old English words: hrisen, which was an adjective meaning brushwood-covered derived from hris meaning brushwood or scrub, and beorg which meant hill. The plural forms are hrisenan beorgas. The spelling in the various documents where the name is found is, as usual, very variable. In the 10th and 11th centuries it had the following forms:

- easteran hrisanbyrge (East Risborough)

- risenbeorgas

- hrisebyrgan be cilternes efese (brushwood-covered hills by Chiltern eaves)

- risebergh (in Domesday Book 1086).

In the 13th century it appears as parva risenburgh (Little Risborough) and in 1346, in the Patent Rolls, for the first time as monekenrisbourgh and again in 1392 as munken ryseberg.[3]

(The prefix 'Monks' is explained under History below).

History

An estate with boundaries corresponding closely to the present ecclesiastical parish of Monks Risborough was granted to some unknown person by the King of Mercia in the 8th or 9th century. The details are unknown because the title documents (the"landbook") were destroyed by fire shortly before 903. The Mercian Witan then agreed that a confirmatory charter should be granted and this was executed in 903. This charter, written in Latin, confirmed that the estate had been given by one Athulf to his daughter Aethelgyth.[4] A description in Anglo-Saxon of the boundaries of the estate was endorsed on the charter. There is a 10th-century copy of the document in the British Library.[5]

Then, at some date between 903 and 994, the estate was given to Christ Church Cathedral at Canterbury and in 994 it was held by Sigeric, who was then the Archbishop of Canterbury. In that year marauders from Scandinavia ravaged Kent and threatened to burn down Canterbury Cathedral unless they were bought off. The Archbishop had insufficient money and sent to Aescwig, Bishop of Dorchester-on-Thames to ask him for a loan. He offered the estate at East Risborough (as it was then described) as security. Money was sent, the cathedral was saved and East Risborough was transferred to Aescwig in the presence of the King and Witan, who at the same time freed the estate from all secular burdens except the obligation for military service and for contributions to bridges and fortresses. At a date between 994 and 1002 Aescwig conveyed the estate back to Canterbury, where Aelfric was now Archbishop after the death of Sigeric. Aelfric in turn died in 1005 and by his will he left his interest in East Risborough to Christ Church Priory, Canterbury. Thereafter it was not owned by the Archbishop but by the monks of the Priory as a community, represented by their Prior – hence "Monks" Risborough – and, even after the Norman Conquest, it continued to enjoy the freedom from liabilities granted in 994.[6]

At the time of the Domesday survey in 1086 the tenant-in-chief of the manor was Archbishop Lanfranc, a stern and very capable man, rivalling the King himself in statesmanship,[7] who had been appointed to the see of Canterbury in 1070 after the Conquest. He held it by frankalmoin.[8] Domesday Book records that the manor was assessed at 30 hides and that there was land there for 14 ploughs. Of these the lord's demesne accounted for 16 hides and 2 ploughs. There were 32 villeins and 8 cottagers and they had 12 ploughs. There were also 4 slaves. These would be only the male heads of families (except for slaves who may have been counted as individuals) and the total has to be multiplied by an arbitrary figure (4 or 5 is usual) for an estimate of the total including women and children.[9] We can therefore assume that the total population was something less than 200 in 1086. There was meadow for 4 plough teams and woodland sufficient for 300 pigs. The value was stated to be £16 in 1086 and also in the time of Edward the Confessor but only £5 immediately after the conquest in 1066. The entry concludes "Asgar the Constable held this manor from Christ Church Canterbury before 1066 on condition that it could not be separated from the Church".[10]

The Manor was then part (with Bledlow, Horsenden and Princes Risborough) of the Hundred of Risborough. This was one of the Three Hundreds of Aylesbury, which by the 14th century were consolidated into the Hundred of Aylesbury.[11]

In 1535, immediately before the dissolution of the monasteries, King Henry VIII, acting by Thomas Cromwell, ordered a valuation to be made of all the ecclesiastical property in England. The manor of Monks Risborough was included in this valuation under the heading "Properties of the Church of Christ at Canterbury". The Manor, which was let out at a rent by the Priory, was shown as worth the 'farm' or rent of £9 a year. The mills were shown separately (£25.8s.11d a year), as were sales from the woods (about 60s) and 'other perquisites' (12s). The total annual value, after making allowable deductions, was returned at £34.11s.7d.[12] The church was valued separately from the manor and the Rectory was not shown as property of the Priory. It was shown separately as part of the Deanery of Risborough within the Diocese of Lincoln but within the exempt jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Canterbury and worth £30 a year.[13]

Christ Church Priory was finally dissolved in 1539 and the manor of Monks Risborough was put up for sale by the Royal Commissioners in 1541. It changed hands on sale on several subsequent occasions until it became vested in the Earl of Buckinghamshire in the 18th or early 19th Century.[14]

Buckinghamshire was transferred from Lincoln to the Diocese of Oxford in 1837 and the Bishop of Oxford then became patron of the living.[14]

Enclosure of the parish

Monks Risborough resisted the pressure to enclose the common lands and open fields and to do away with rights of common until a later date than most places, but a local Act of Parliament was eventually obtained in 1830 (11 Geo IV) entitled 'An Act for inclosing lands in the Parish of Monks Risborough in the County of Buckingham'. The Royal Assent was granted on 29 May 1830 and the first meeting of the three Commissioners appointed to investigate the matter and make the Award was held in the Cross Keys Inn at Princes Risborough on 17 June 1830. There seems to have been opposition, because the Award was not completed until 23 September 1839. It is said that meetings to oppose the enclosure were held in the Three Crowns Inn at Askett.[15] Eventually the opposition was overcome and all the former common lands were allotted to individual parishioners. The full details, with a large scale map of the parish as it then was, are set out in the Award.

A number of fields were allotted to the Rector in lieu of tithe, which then ceased to be payable (except in respect of woodlands). Other fields were allotted for the benefit of the poor, who lost their rights over the common lands such as the right to gather wood in certain woodlands. Originally the rents of these fields were used to buy coal. The fields are now vested in the Trustees of Monks Risborough Parochial Charities and they have a wider discretion as to the charitable purposes for which the income can be applied.[16] All the woodlands in the parish were allotted to the Lord of the Manor, the Earl of Buckinghamshire.

A field in a district then called Rumborough was allotted to be used for recreation; this is now the Monks Risborough cricket pitch.

The Award also designated land for footpaths and roads, following the existing tracks as shown on the plans. Most footpaths were to be 8 feet (2.4 m) wide and most roads 30 feet (9.1 m) wide. These did not include the Aylesbury Road which was already a public highway and always referred to in the Award as 'the Turnpike Road'. Special provision was made about Whiteleaf Cross as mentioned below in the section on the cross.[17]

The parish in antiquity

On Whiteleaf Hill, which extends above the hamlet of Whiteleaf to the top of the scarp at 813 ft (248 m), is an oval Neolithic barrow (National Grid SP 822040), which was first excavated by Sir Lindsay Scott between 1934 and 1939, when the work was interrupted by the Second World War and the excavator died before he had had an opportunity to publish more than interim notes on his findings. A fuller report was published from his notes in 1954.[18] The site was re-excavated from 2002 to 2006 by Oxford Archaeology (assisted by the Princes Risborough Countryside Group) and their report was published in 2007.[19]

There was a single burial within the barrow, a middle aged man between 5'6" and 5'9" in height, with a long and narrow skull (a type found in the Neolithic period), badly worn teeth and arthritic joints.[20] The remains appeared to have been placed between two large vertical posts, 1.2 metres apart. Pottery shards and animal bones were found at the core of the mound and the excavators suggest that these came from ceremonial feasting when the mound was built.[21]

After the re-excavation the soil was replaced, following Sir Lindsay Scott's plans and drawings, so that the appearance of the barrow now corresponds with that existing at the start of excavations in 1934.

Radio-carbon dating has shown that the death, the burial and the building of the mound probably all took place within the period 3,750–3,100 B.C., but at different times within that period. The ceremonial burial could have been 45–150 years after the death and the completion of the mound could be up to 200 years after that. Similar delays have been shown to have occurred at other sites.[22]

The status of the individual and the actual nature of the events are unknown, but he must have been a man of significance in local society.

Two other supposed barrows were scheduled as Ancient Monuments but have now been shown by the same excavators not to be burial mounds. They are sited to the north of the oval barrow along the top of the hill. One is likely to have been the base of a windmill, probably in use for a relatively short time in the late 16th and early 17th century. The other is a natural mound, but many chipped flints were found there and it seems to have been a site where flints were obtained and partially worked (for finishing elsewhere) during the late neolithic period.

Just to the south of the oval barrow, crossing the path leading to the car park, another earthwork was investigated and was found to be a cross-ridge dyke about 140 m long across the southern end of the narrowest part of the ridge. Its date is uncertain, but the excavators considered that it might be a late Bronze Age boundary.

The ancient trackway known as the Icknield Way, which ran from the Wash to Wessex, passed through the parish. It here consisted of two separate tracks, the Upper Icknield Way and the Lower Icknield Way, supposedly for winter and summer use respectively, though Christopher Taylor suggests that the upper route follows the prehistoric track, while the lower route was a Roman road which followed the same general line but on flat land more suitable for Roman methods of road construction.[23] The route of the Lower Icknield Way is now followed by the B4009, while the Upper Icknield Way is here still a muddy track, except where it passes through the hamlet of Whiteleaf

A section of the extensive earthwork known as Grim's Ditch crosses the parish much further south (Map square SP 8203). This is thought to be an Iron Age boundary dyke.

The church

The parish church is dedicated to St Dunstan. The present building, which replaced an earlier church, dates mainly from the 14th and 15th centuries, restored and in part renewed by G.E. Street in 1863–64. It is built of flint and has a chancel, nave with two aisles, north transept and a square tower at the west end.

The nave arcades have octagonal piers and are of 14th-century date, the south aisle being earlier than the north. The transept may be earlier. However, the windows are all in the perpendicular style of the 15th century, except those in the south aisle, where the eastern window is modern but the windows in the south wall are 14th century. In the 15th century the roof was raised and the clerestorey built. The old roof line can still be seen on the west wall of the nave. The present roof of the nave and south porch are 15th century, when the chancel was also rebuilt. The chancel roof is modern. The font is Norman, of the 'Aylesbury' late 12th-century type, and presumably came from the earlier church. There is a 15th-century chancel screen, though without its original tracery, with crudely re-painted figures below. At the left side of the chancel arch is the opening for the door which led to the rood loft. There are three memorial brasses in the church, two of the 15th century and the other undated. A random collection of 14th and 15th century stained glass has been put together in a window in the south aisle, including a small 14th century Madonna and child.[24]

St Dunstan's Church from south-east

St Dunstan's Church from south-east Interior of Church

Interior of Church Norman font of 'Aylesbury' type

Norman font of 'Aylesbury' type Madonna & Child (14th-century glass)

Madonna & Child (14th-century glass)

Whiteleaf Cross

Whiteleaf Hill, has a large cross with a triangular base cut into the chalk on the side of the hill, making an important landmark for miles around, known as Whiteleaf Cross. The date and origin of this cross are unknown. It was mentioned as an antiquity by Francis Wise in 1742, but no earlier reference has been found. The cross is not mentioned in any description of the area before 1700.[25]

The Act for enclosing the common lands in the Parish (see above) specifically required that "in order to preserve within the parish of Monks Risborough the ancient memorial or land mark there called White Cliffe Cross" the Commissioners were to allot to the Lord of the Manor the cross itself and "so much of the land immediately surrounding it as shall in the judgment of the Commissioners be necessary and sufficient for rendering the same conspicuous" and that it should not be planted or enclosed and should for ever thereafter remain open. The Lord of the Manor was to be responsible to renew and repair it. In the event the Commissioners allotted 7 acres (2.8 ha) of land for this purpose.[26]

Various buildings and places of interest

Still existing

Cottages

There are picturesque cottages (some half-timbered) in Burton Lane in the old village and also in the hamlets of Askett and Whiteleaf. Most of the interiors have been modernised and in places two or more have been combined to make a larger house. They range from the late 16th to the early 18th century.[27]

Monks Risborough C of E Primary School

On the Aylesbury Road to the west of the Parish is Monks Risborough C of E Primary School , first founded in 1855[28] as a National School[29][30] and expanded mid-20th century. The school teaches around 200 children aged 5 to 11.

Pigeon House

The "curious" northern doorway |

The Pigeon House |

In the field (now a recreation ground) to the west of the church is a 16th-century pigeon house, where pigeons were bred for food. It has a curious northern doorway, which may have been brought from elsewhere.[31] There are nesting places ('pigeon holes') for 216 pigeons.[32] In later years it formed part of Place Farm and was used as a shelter for cattle. At the end of the 20th century it was cleaned out, repaired and secured.

Railway station

The single track railway line from Princes Risborough to Aylesbury, was constructed in 1863 and converted from broad gauge to standard gauge in 1868, but there was no station at Monks Risborough until 1929. Monks Risborough railway station opened on 11 November 1929 as Monks Risborough and Whiteleaf Halt. It has been called Monks Risborough since 1974.

Formerly existing

Gallows

In the reign of Edward I, when the King was calling on his feudal tenants to show their title to rights which they claimed to exercise, the Prior of Christchurch, Canterbury claimed to be entitled to maintain at Monks Risborough a gallows, a tumbril[33] and a pillory. The King's counsel, objecting to the claim, said that there was no pillory at Monks Risborough.[34] It is said that the Cadsden Road used to be known as Gallows Lane and the crossing of the Upper Icknield Way with Cadsden Road as Gallows Cross.[35]

Mills

Domesday Book does not mention any mill at Monks Risborough, but there was certainly a mill there by the 14th century. During the 14th and 15th centuries the millward was several times brought before the manor court accused of overcharging.[8] In 1535 the valuation, made prior to the dissolutioon of the monasteries, showed Monks Risborough (part of the property of the Priory of Christchurch, Canterbury) as having two mills, which brought in for the Priory an income of £25.8s.11d a year.[36] In the 17th century the then Lord of the Manor owned two mills at his death, a watermill and a windmill on 'Brokenhill'[8] Excavations in 2002/06 found the site of a former windmill on the top of Whiteleaf Hill, thought to have been there in the 16th and 17th centuries. The watermill was at the house still called Mill House in Mill Lane. The map attached to the Inclosure Award of 1839 showed this property, described as 'The Ham. Mill House', with a millpond behind it and two fields marked as Mill Meadow and Mill Mead[37] It is not known when it had ceased to be used as a working mill.

Turnpike

The road from Princes Risborough to Aylesbury (now the A4010 and called the Aylesbury Road) passes through the middle of the parish, and was made a Turnpike Road under a private Act of Parliament of 1795, which created a Turnpike Trust to be responsible for the maintenance and improvement of the road from Ellesborough to West Wycombe[38] There were barriers at places along the road where vehicles had to stop and tolls were collected. One toll gate and adjoining toll booth was in Monks Risborough near the boundary with Princes Risborough.[39]

Commercial buildings

There have been no shops in the old village since the early 20th century, when there was a Butcher and slaughterhouse (now a dental practice) on the Aylesbury Road, a Blacksmith's forge on the corner with Burton Lane (the house next to it is still called Forge Cottage), and a pub, the Nag's Head (now a house) on the opposite corner. On Burton Lane there was a Saddler and Harness maker (who also made ropes) and a Bakehouse where bread continued to be baked until 1966. Earlier the bakehouse used also to be a general store.[32] In the later 20th century Aston & Full had a factory on the north side of Mill Lane. In the early 21st century the land was re-designated for residential use.

References

- Baines, Arnold H. J: The Boundaries of Monks Risborough in Records of Buckinghamshire Vol 23 (Bucks Archaeological Society. 1981) pp. 76–101

- Childe, V.G. and Isobel Smith: The Excavation of a Neolithic Barrow on Whiteleaf Hill, Bucks in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society for 1954, (New Series, Vol.XX, no.8), pp. 212–30

- Darby, Henry C: Domesday England (Cambridge, 1977)

- Domesday Book vol 13 Buckinghamshire. Text & translation edited by John Morris (Phillimore, Chichester. 1978)

- Hey, Gill, Caroline Dennis & Andrew Mayes: Archaeological Investigations on Whiteleaf Hill, Princes Risborough, Buckinghamshire, 2002-6 in Records of Buckinghamshire, Vol 47 part 2, pp. 1–80 (Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society, Aylesbury. 2007)

- Inclosure Award for the Parish of Manks Risborough dated 23 September 1839 (in the custody of the County Archivist at County Hall, Aylesbury)

- Mawer, A. and Stenton, F.M: The Place Names of Buckinghamshire (Cambridge, 1925)

- McGown, E.D: Monks Risborough. The Cottages (2003)

- Pevsner, Nikolaus & Elizabeth Williamson: Buckinghamshire (The Buildings of England – Penguin Books. 2nd edition. 1994)

- RCHMB = Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England): An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Buckinghamshire, Volume 1 (1912)

- Rogers, Jane & Venetia Lascelles: Beating the Bounds of Monks Risborough Parish (2003)

- Valor Ecclesiasticus (Record Office 1818 &c)

- VHCB = Victoria History of the County of Buckingham, Volume 2, ed: William Page F.S.A. (1908)

Notes

- ↑ Large scale plans of the parish (with field names) can be found in Rogers & Lascelles

- ↑ All the information in this section comes from the Ordnance Survey map on a scale of 1:25,000 and from Baines p.81 and Rogers & Lascelles

- ↑ see Mawer & Stenton

- ↑ Baines pp.76–77

- ↑ Stowe ms no.22 For text, translation & commentary see Baines pp.77–91. The map on p.81 shows how closely the boundaries correspond with the present parish

- ↑ Baines p.91

- ↑ David C. Douglas: William the Conqueror (1966) pp.318–9

- 1 2 3 VHCB p.257

- ↑ Darby pp.87–8

- ↑ Domesday Book 143d(2,3)

- ↑ VHCB p.245

- ↑ Valor Ecclesiasticus Volume 1, p.15

- ↑ Valor Ecclesiasticus Vol 4, p.249

- 1 2 VHCB p.259

- ↑ McGown. She cites no authority for this information. The files of the Bucks Chronicle may throw light on it

- ↑ Rogers & Lascelles (inside front cover)

- ↑ See the Inclosure Award for all the information in this section

- ↑ Childe and Smith

- ↑ Hey et al. Unless another source is noted, the information below comes from this report, which includes a full bibliography

- ↑ The human remains are described in more detail in Childe & Smith at p.220

- ↑ The pottery is described and illustrated in Childe & Smith pp.221–8

- ↑ Hey et al. For the figures see the report by Alex Bayliss & Frances Healy on pp.69–70

- ↑ Christopher Taylor: Roads and Tracks of Britain (London 1979) pp.65–68

- ↑ Pevsner & Williamson pp.570–1; RCHMB pp.257–63; VHCB pp.258ff. The latter two works both have a plan of the church. They took a different view to Pevsner & Williamson on the dating of some parts of the church.

- ↑ Hey et al. p.74; Pevsner & Williamson p.607 (under Princes Risborough)

- ↑ Inclosure Award

- ↑ Pevsner & Williamson p.571. The RCHMB describes several in detail in their condition in 1912

- ↑ Wycombe District Council (1997), Conservation Area Character Survey Monks Risborough, Wycombe District Council

- ↑ See

- ↑ Description of Monks Risborough from J. J. Sheahan, 1861.

- ↑ RCHMB

- 1 2 McGown

- ↑ A tumbril was a chair or stool to which a miscreant could be tied and exposed to the public or ducked in a pond. (Oxford English Dictionary 2nd edition)

- ↑ Placita de Quo Warranto (London 1818) p.86; VHCB p.257

- ↑ Baines p.79; Rogers & Lascelles pp.10 & 16

- ↑ Valor Ecclesiasticus vol.1, p.15

- ↑ Inclosure Award: parcels no'd: 481-3

- ↑ The private Act is 35 Geo III c.149

- ↑ The map annexed to the Inclosure Award of 1839 shows a small building (possibly a hut) on the right of the road, coming from Princes Risborough, at about the place where the road signs for Monks and Princes Risborough now stand.

External links

![]() Media related to Monks Risborough at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Monks Risborough at Wikimedia Commons