Music in early modern Scotland

Music in early modern Scotland includes all forms of musical production in Scotland between the early sixteenth century and the mid-eighteenth century. In this period the court followed the European trend for instrumental accompaniment and playing. Scottish monarchs of the sixteenth century were patrons of religious and secular music, and some were accomplished musicians. In the sixteenth century the playing of a musical instrument and singing became an expected accomplishment of noble men and women. The departure of James VI to rule in London at the Union of Crowns in 1603, meant that the Chapel Royal, Stirling Castle largely fell into disrepair and the major source of patronage was removed from the country. Important composers of the early sixteenth century included Robert Carver and David Peebles. The Lutheranism of the early Reformation was sympathetic to the incorporation of Catholic musical traditions and vernacular songs into worship, exemplified by The Gude and Godlie Ballatis (1567). However, the Calvinism that came to dominate Scottish Protestantism led to the closure of song schools, disbanding of choirs, removal of organs and the destruction of music books and manuscripts. An emphasis was placed on the Psalms, resulting in the production of a series of Psalters and the creation of a tradition of unaccompanied singing.

Despite the attempts of the Kirk to limit the tradition of secular popular music, it continued. This period saw the adoption of the highland bagpipes and the fiddle. Ballads, some of which probably date from the Medieval period, existed as part of an distinctive oral tradition. Allan Ramsey advocated the creation of a national musical tradition and collaborated with Italian composer and cellist Lorenzo Bocchi on the first Scottish opera the Gentle Shepherd. A musical culture developed around Edinburgh and a number of composers began to produce collections of Lowland and Highland tunes grafted on to Italian musical forms. By the middle of the eighteenth century a number of Italian musicians and composers were resident in Scotland and Scottish composers of national significance had begun to emerge.

The court and noble households

In this era Scotland followed the trend of Renaissance courts for instrumental accompaniment and playing. James V, as well as being a major patron of sacred music, was a talented lute player and introduced French chansons and consorts of viols to his court, although almost nothing of this secular chamber music survives.[1] The return of Mary, Queen of Scots from France in 1561 to begin her personal reign, and her position as a Catholic, gave a new lease of life to the choir of the Chapel Royal, but the destruction of Scottish church organs meant that instrumentation to accompany the mass had to employ bands of musicians with trumpets, drums, fifes, bagpipes and tabors. Like her father she played the lute, virginals and (unlike her father) was a fine singer.[2] She brought French musical influences with her, employing lutenists and viol players in her household.[3]

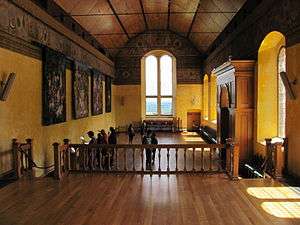

James VI (r. 1566–1625) was a major patron of the arts in general. He rebuilt the Chapel Royal at Stirling in 1594 and the choir was used for state occasions like the baptism of his son Henry.[4] He followed the tradition of employing lutenists for his private entertainment, as did other members of his family.[5] When he went south to take the throne of England in 1603 as James I, he removed one of the major sources of patronage in Scotland. The Chapel Royal now began to fall into disrepair, and the court in Westminster would be the only major source of royal musical patronage.[4] Holyrood Abbey was remodelled as a chapel for Charles I's royal visit in 1633 and reclaimed by Charles II after the Restoration, becoming a centre of worship again during the future James VII's residency in the early 1680s, but was sacked by an anti-papist mob during the Glorious Revolution in 1688.[6]

These fashions permeated noble households, where resident musicians were employed, including viol and lute players. As elsewhere in Europe, musical ability became one of the major achievements expected of a nobleman or woman. Musicians were clearly employed as teachers for the children of the household, both male and female.[7] There is evidence for the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries of lessons being given in a variety of instruments and singing, and of the purchase of sheet music and instruments (including the virginals and harpsichords). In the Highlands clan chiefs continued to employ harpists, and increasingly, pipers as fili and bards, whose prowess and ability to glorify their ancestors was a key element in underlying a clan's status and heritage into the seventeenth century.[8] The earliest printed collection of secular music in Scotland was by publisher John Forbes in Aberdeen in 1662. Songs and Fancies: to Thre, Foure, or Five Partes, both Apt for Voices and Viols, known as Forbes' Cantus, was printed three times in the next twenty years. It contained 77 songs, of which 25 were of Scottish origin.[9]

Church music

The outstanding Scottish composer of the first half of the sixteenth century was Robert Carver (c. 1488–1558), a canon of Scone Abbey. His complex polyphonic music could only have been performed by a large and highly trained choir such as the one employed in the Scottish Chapel Royal. James V was also a patron to figures including David Peebles (c. 1510–79?), whose best known work "Si quis diligit me" (text from John 14:23), is a motet for four voices. These were probably only two of many accomplished composers from this era, whose work has largely only survived in fragments.[10] Much of what survives of church music from the first half of the sixteenth century is due to the diligent work of Thomas Wode (d. 1590), vicar of St Andrews, who compiled a part book from now lost sources, which was continued by unknown hands after his death.[11]

The Reformation had a severe impact on church music. The song schools of the abbeys, cathedrals and collegiate churches were closed down, choirs disbanded, music books and manuscripts destroyed and organs removed from churches.[12] The Lutheranism that influenced the early Scottish Reformation attempted to accommodate Catholic musical traditions into worship, drawing on Latin hymns and vernacular songs. The most important product of this tradition in Scotland was The Gude and Godlie Ballatis (1567), which were spiritual satires on popular ballads composed by the brothers James, John and Robert Wedderburn. Never adopted by the kirk, they nevertheless remained popular and were reprinted from the 1540s to the 1620s.[13]

Later the Calvinism that came to dominate the Scottish Reformation was much more hostile to Catholic musical tradition and popular music, placing an emphasis on what was biblical, which meant the Psalms. The Scottish Psalter of 1564 was commissioned by the Assembly of the Church. It drew on the work of French musician Clément Marot, Calvin's contributions to the Strasbourg Psalter of 1539 and English writers, particularly the 1561 edition of the Psalter produced by William Whittingham for the English congregation in Geneva. The intention was to produce individual tunes for each psalm, but of 150 psalms, 105 had proper tunes and in the seventeenth century, common tunes, which could be used for psalms with the same metre, became more frequent. Because whole congregations would now sing these psalms, unlike the trained choirs who had sung the many parts of polyphonic hymns,[13] there was a need for simplicity and most church compositions were confined to homophonic settings.[14]

During his personal reign James VI attempted to revive the song schools, with an act of parliament passed in 1579, demanding that councils of the largest burghs set up "ane sang scuill with ane maister sufficient and able for insturctioun of the yowth in the said science of musik".[15] Five new schools were opened within four years of the act and by 1633 there were at least twenty-five. Most of those without song schools made provision within their grammar schools.[15] Polyphony was incorporated into editions of the Psalter from 1625, but usually with the congregation singing the melody and trained singers the contra-tenor, treble and bass parts.[13] However, the triumph of the Presbyterians in the National Covenant of 1638 led to and end of polyphony and a new psalter in common metre, but without tunes, was published in 1650.[16] In 1666 The Twelve Tunes for the Church of Scotland, composed in Four Parts (which actually contained 14 tunes), designed for use with the 1650 Psalter, was first published in Aberdeen. It would go through five editions by 1720. By the late seventeenth century these two works had become the basic corpus of the psalmody sung in the kirk.[17]

Popular music

The secular popular tradition of music continued, despite attempts by the Kirk, particularly in the Lowlands, to suppress dancing and events like penny weddings at which tunes were played. Large numbers of musicians continued to perform, including the fiddler Pattie Birnie and the piper Habbie Simpson (1550–1620).[18]

The first clear reference to the use of the Highland bagpipes is from a French history, which mentions their use at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh in 1547.[19] George Buchanan claimed that they had replaced the trumpet on the battlefield. This period saw the creation of the ceòl mór (the great music) of the bagpipe, which reflected its martial origins, with battle-tunes, marches, gatherings, salutes and laments.[19] The Highlands in the early seventeenth century saw the development of piping families including the MacCrimmonds, MacArthurs, MacGregors and the Mackays of Gairloch. There is also evidence of adoption of the fiddle in the Highlands with Martin Martin noting in his A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland (1703) that he knew of eighteen players in Lewis alone.[20]

There is evidence of ballads from this period. Some may date back to the late Medieval era and deal with events and people that can be traced back as far as the thirteenth century, including "Sir Patrick Spens" and "Thomas the Rhymer", but for which we do not have evidence until the eighteenth century.[21] Scottish ballads are distinct, showing pre-Christian influences in the inclusion of supernatural elements such as the fairies in the Scottish ballad "Tam Lin".[22] They remained an oral tradition until the increased interest in folk songs in the eighteenth century led collectors such as Bishop Thomas Percy to publish volumes of popular ballads.[22] The oppression of secular music and dancing began to ease between about 1715 and 1725 and the level of musical activity was reflected in a flood of musical publications in broadsheets and compendiums of music such as the makar Allan Ramsay's verse compendium The Tea Table Miscellany (1723) and William Thomson's Orpheus Caledonius (1725).[18]

Classical music

From the late seventeenth music became less an accomplishment of the gentle classes and increasingly a skill pursued by professionals. It was enjoyed in otherwise silent concert rooms rather than as incidental entertainment in the houses of royalty and nobles.[23] The German flute was probably introduced into Scotland towards the end of the seventeenth century.[24] The Italian style of classical music was probably first brought to Scotland by the Italian cellist and composer Lorenzo Bocchi, who travelled to Scotland in the 1720s, introducing the cello to the country and then developing settings for Lowland Scots songs. He possibly had a hand in the first Scottish Opera, the pastoral The Gentle Shepherd, with libretto by Allan Ramsay.[25] Music in Edinburgh prospered through the patronage of figures including the merchant Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, who was also a noted composer, violinist and harpiscordist.[26] The growth of a musical culture in the capital was marked by the incorporation of the Musical Society of Edinburgh in 1728.[27]

A group of Scottish composers began to respond to Allan Ramsey's call to "own and refine" their own musical tradition, creating what James Johnson has characterised as the "Scots drawing room style", taking primarily Lowland Scottish tunes and adding simple figured basslines and other features from Italian music that made them acceptable to a middle class audience.[28] It gained momentum when major Scottish composers like James Oswald and William McGibbon became involved around 1740. Oswald's Curious Collection of Scottish Songs (1740) was one of the first to include Gaelic tunes alongside Lowland ones, setting a fashion common by the middle of the century and helping to create a unified Scottish musical identity. However, with changing fashions there was a decline in the publication of collections of specifically Scottish collections of tunes, in favour of their incorporation into British collections.[28] By the mid-eighteenth century there were Italians resident in Scotland, acting as composers and performers. These included Nicolò Pasquali, Giusto Tenducci and Fransesco Barsanti.[29] Thomas Erskine, 6th Earl of Kellie (1732–81) was one of the most important British composers of his era, and the first Scot known to have produced a symphony.[26]

References

Notes

- ↑ J. Patrick, Renaissance and Reformation (London: Marshall Cavendish, 2007), ISBN 0-7614-7650-4, p. 1264.

- ↑ A. Frazer, Mary Queen of Scots (London: Book Club Associates, 1969), pp. 206–7.

- ↑ M. Spring, The Lute in Britain: A History of the Instrument and Its Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), ISBN 0-19-518838-1, p. 452.

- 1 2 P. Le Huray, Music and the Reformation in England, 1549–1660 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), ISBN 0-521-29418-5, pp. 83–5.

- ↑ T. Carter and J. Butt, The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Music (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-521-79273-8, pp. 280, 300, 433 and 541.

- ↑ D. J. Smith, "Keyboard music in Scotland: genre, gender, context", in J. Porter, ed., Defining Strains: The Musical Life of Scots in the Seventeenth Century (Peter Lang, 2007), ISBN 3-03910-948-0, p. 99.

- ↑ D. MacKinnon, "'I have now a book of songs of her writing: Scottish families, orality, literacy and the transmission of musical culture c. 1500-c. 1800", in E. Ewan and J. Nugent, Finding the Family in Medieval and Early Modern Scotland (Ashgate, 2008), ISBN 0-7546-6049-4, pp. 44–6.

- ↑ K. Brown, Noble Society in Scotland: Wealth, Family and Culture from Reformation to Revolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), ISBN 0-7486-1299-8, pp. 216–18.

- ↑ A. D. McLucas, "Forbes' Cantus, Songs and Fancies revisited", in J. Porter, ed., Defining Strains: The Musical Life of Scots in the Seventeenth Century (Peter Lang, 2007), ISBN 3-03910-948-0, p. 269.

- ↑ J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0-7486-1455-9, p. 118.

- ↑ J. R. Baxter, "Culture: Renaissance and Reformation (1460–1560)", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 130–2.

- ↑ A. Thomas, "The Renaissance", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0-19-162433-0, pp. 198–9.

- 1 2 3 J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 187–90.

- ↑ Thomas, "The Renaissance", p. 198.

- 1 2 G. Munro, "'Sang schools' and 'music schools': music education in Scotland 1560–1650", in S. F. Weiss, R. E. Murray, Jr., and C. J. Cyrus, Music Education in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance (Indiana University Press, 2010), ISBN 0-253-00455-1, p. 67.

- ↑ J. R. Baxter, "Music, ecclesiastical", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 431–2.

- ↑ B. D. Spinks, A Communion Sunday in Scotland ca. 1780: Liturgies and Sermons (Scarecrow Press, 2009), ISBN 0-8108-6981-0, pp. 143–4.

- 1 2 J. Porter, "Introduction" in J. Porter, ed., Defining Strains: The Musical Life of Scots in the Seventeenth Century (Peter Lang, 2007), ISBN 3-03910-948-0, p. 22.

- 1 2 J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0-7486-1455-9, p. 169.

- ↑ J. Porter, "Introduction" in J. Porter, ed., Defining Strains: The Musical Life of Scots in the Seventeenth Century (Peter Lang, 2007), ISBN 3-03910-948-0, p. 35.

- ↑ E. Lyle, Scottish Ballads (Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 2001), ISBN 0-86241-477-6, pp. 9–10.

- 1 2 J. Black, et. al., eds, "Popular Ballads" in The Broadview Anthology of British Literature: The Restoration and the Eighteenth Century (Broadview Press, 2006), ISBN 1-55111-611-1, pp. 610–17.

- ↑ Edward Lee, Music of the People: a Study of Popular Music in Great Britain (London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1970), p. 53.

- ↑ P. Holman, "A little light on Lorenzo Bocchi: an Italian in Edinburgh and Dublin", in R. Cowgill and P. Holman, eds, Music in the British Provinces, 1690–1914 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), ISBN 0-7546-3160-5, p. 79.

- ↑ R. Cowgill and P. Holman, "Introduction: centres and peripheries", in R. Cowgill and P. Holman, eds, Music in the British Provinces, 1690–1914 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), ISBN 0-7546-3160-5, p. 4.

- 1 2 N. Wilson, Edinburgh (Lonely Planet, 3rd edn., 2004), ISBN 1-74059-382-0, p. 33.

- ↑ E. G. Breslaw, Doctor Alexander Hamilton and Provincial America (Louisiana State University Press, 2008), ISBN 0-8071-3278-0, p. 41.

- 1 2 M. Gelbart, The Invention of "Folk Music" and "Art Music" (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), ISBN 1-139-46608-9, p. 30.

- ↑ Gelbart, The Invention of "Folk Music" and "Art Music", p. 36.

Bibliography

- Baxter, J. R., "Music, ecclesiastical", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- Black, J., et al., eds, "Popular Ballads" in The Broadview Anthology of British Literature: The Restoration and the Eighteenth Century (Broadview Press, 2006), ISBN 1-55111-611-1.

- Breslaw, E. G., Doctor Alexander Hamilton and Provincial America (Louisiana State University Press, 2008), ISBN 0-8071-3278-0.

- Brown, K., Noble Society in Scotland: Wealth, Family and Culture from Reformation to Revolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), ISBN 0-7486-1299-8.

- Carter, T., and Butt, J., The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Music (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-521-79273-8.

- Cowgill, R., and Holman, P., "Introduction: centres and peripheries", in R. Cowgill and P. Holman, eds, Music in the British Provinces, 1690–1914 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), ISBN 0-7546-3160-5.

- Dawson, J. E. A., Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0-7486-1455-9.

- Frazer, A., Mary Queen of Scots (London: Book Club Associates, 1969).

- Gelbart, M., The Invention of "Folk Music" and "Art Music" (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), ISBN 1-139-46608-9.

- Holman, P., "A little light on Lorenzo Bocchi: an Italian in Edinburgh and Dublin", in R. Cowgill and P. Holman, eds, Music in the British Provinces, 1690–1914 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), ISBN 0-7546-3160-5.

- Le Huray, P., Music and the Reformation in England, 1549–1660 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), ISBN 0-521-29418-5.

- Lee, Edward, Music of the People: a Study of Popular Music in Great Britain (London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1970).

- Lyle, E., Scottish Ballads (Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 2001), ISBN 0-86241-477-6.

- MacKinnon, D., "'I have now a book of songs of her writing: Scottish families, orality, literacy and the transmission of musical culture c. 1500-c. 1800", in E. Ewan and J. Nugent, Finding the Family in Medieval and Early Modern Scotland (Ashgate, 2008), ISBN 0-7546-6049-4.

- McLucas, A. D., "Forbes' Cantus, Songs and Fancies revisited", in J. Porter, ed., Defining Strains: The Musical Life of Scots in the Seventeenth Century (Peter Lang, 2007), ISBN 3-03910-948-0.

- Munro, G., "'Sang schools' and 'music schools': music education in Scotland 1560–1650", in S. F. Weiss, R. E. Murray, Jr., and C. J. Cyrus, Music Education in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance (Indiana University Press, 2010), ISBN 0-253-00455-1.

- Patrick, J., Renaissance and Reformation (London: Marshall Cavendish, 2007), ISBN 0-7614-7650-4.

- Porter, J., "Introduction" in J. Porter, ed., Defining Strains: The Musical Life of Scots in the Seventeenth Century (Peter Lang, 2007), ISBN 3-03910-948-0.

- Smith, D. J., "Keyboard music in Scotland: genre, gender, context", in J. Porter, ed., Defining Strains: The Musical Life of Scots in the Seventeenth Century (Peter Lang, 2007), ISBN 3-03910-948-0

- Spinks, B. D., A Communion Sunday in Scotland ca. 1780: Liturgies and Sermons (Scarecrow Press, 2009), ISBN 0-8108-6981-0.

- Spring, M., The Lute in Britain: A History of the Instrument and Its Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), ISBN 0-19-518838-1.

- Thomas, A., "The Renaissance", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0-19-162433-0.

- Wilson, N., Edinburgh (Lonely Planet, 3rd edn., 2004), ISBN 1-74059-382-0.

- Wormald, J., Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3.