Scottish religion in the seventeenth century

Scottish religion in the seventeenth century includes all forms of religious organisation and belief in the Kingdom of Scotland in the seventeenth century. During the sixteenth century, Scotland had undergone a Protestant Reformation that created a predominately Calvinist national kirk, which was strongly Presbyterian in outlook. James VI favoured doctrinal Calvinism, but also episcopacy. His son Charles I authorised a book of canons that made him head of the Church and enforced the use of a new liturgy, seen as an English-style Prayer Book. In the resulting rebellion the Scottish bishops were formally expelled from the Church and representatives of various sections of Scottish society drew up the National Covenant. In the subsequent Bishop's Wars the Scottish Covenanters emerged as virtually independent rulers. Charles I's failure led indirectly to the English civil war (1642–46). The Covenanters intervened on the side of Parliament, who were victorious, but became increasingly alienated from the Parliamentary regime. The Scottish defeats in the subsequent Second and Third civil wars, led to English occupation and incorporation in a Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland led by Oliver Cromwell from 1652 and the imposition of religious toleration for Protestants. The Scottish Covenanters divided into parties of Resolutioners and Protesters.

After the Restoration in 1660, Scotland regained its national kirk, but also episcopacy. About a third of the clergy refused to accept the new settlement and particularly in the south-west ministers took to preaching in the open fields in conventicles, often attracting thousands of worshippers. The government alternated between accommodation and persecution. There were risings in 1666 and 1679, which were defeated by government forces. The Society People who continued to resist the government, known as the Cameronians, became increasingly radical. In the early 1680s a more intense phase of persecution began, in what was later to be known in Protestant historiography as "the Killing Time". With the accession of the openly Catholic James VII, there was increasing disquiet among Protestants. After the Glorious Revolution of 1688–89, William of Orange and Mary, the daughter of James, were, accepted as monarchs. The final settlement restored Presbyterianism and abolished the bishops, who had generally supported James. However, William, who was more tolerant than the kirk tended to be, passed acts restoring the Episcopalian clergy excluded after the Revolution.

Protestantism was focused on the Bible and family worship was strongly encouraged. The kirk sessions applied personal and moral discipline. They discouraged group celebrations. Sessions had an administrative burden in the system of poor relief, the administration of the parish school system. They also took over the pursuit of witchcraft cases. The most intense hunt was in 1661–62, but improving economic conditions and increasing scepticism led the practice to peter out towards the end of the century. The numbers of Roman Catholics and the organisation of the Church probably deteriorated, but began to revive with the appointment of a Vicar Apostolic over the mission in 1694.

Events

Background: the Reformation

During the sixteenth century, Scotland underwent a Protestant Reformation that created a predominately Calvinist national kirk, which was strongly Presbyterian in outlook; the Reformation severely reduced the powers of bishops, but did not abolish them. In the earlier part of the century, the teachings of first Martin Luther and then John Calvin began to influence Scotland, particularly through Scottish scholars who had visited continental and English universities and who had often trained in the Catholic priesthood. The influence of the English was also more direct, as they supplied books and distributed Bibles and Protestant literature in the Lowlands when they invaded in 1547. Particularly important was the work of the Lutheran Scot Patrick Hamilton.[1] His execution with other Protestant preachers in 1528, and of the Zwingli-influenced George Wishart in 1546, who was burnt at the stake in St. Andrews on the orders of Cardinal Beaton, did nothing to stem the growth of these ideas. Wishart's supporters, who included a number of Fife lairds, assassinated Beaton soon after and seized St. Andrews Castle, which they held for a year before they were defeated with the help of French forces. The survivors, including chaplain John Knox, were condemned to be galley slaves, helping to create resentment of the French and martyrs for the Protestant cause.[2]

Limited toleration and the influence of exiled Scots and Protestants in other countries, led to the expansion of Protestantism, with a group of lairds declaring themselves Lords of the Congregation in 1557 and representing their interests politically. The collapse of the French alliance and English intervention in 1560 meant that a relatively small, but highly influential, group of Protestants were in a position to impose reform on the Scottish church. A confession of faith, rejecting papal jurisdiction and the mass, was adopted by Parliament in 1560, while the young Mary, Queen of Scots was still in France.[3] Knox, having escaped the galleys and spent time in Geneva, where he became a follower of Calvin, emerged as the most significant figure. The Calvinism of the reformers led by Knox resulted in a settlement that adopted a Presbyterian system and rejected most of the elaborate trappings of the Medieval church. This gave considerable power within the new kirk to local lairds, who often had control over the appointment of the clergy, and resulting in widespread, but generally orderly, iconoclasm. At this point the majority of the population was probably still Catholic in persuasion and the kirk would find it difficult to penetrate the Highlands and Islands, but began a gradual process of conversion and consolidation that, compared with reformations elsewhere, was conducted with relatively little persecution.[4]

The personal reign of the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots (1561–67) eventually ended in civil war, deposition, imprisonment and execution in England. Her infant son James VI was crowned King of Scots in 1567.[5] He was brought up as a Protestant, while the country was run by a series of regents.[6] After he asserted his personal rule from 1583 he favoured doctrinal Calvinism, but also episcopacy.[7]

Covenants and the Civil Wars

James VI's inheritance of the English crown in 1603 led to rule via the Privy Council from London. He also increasingly controlled the meetings of the Scottish General Assembly and increased the number and powers of the Scottish bishops. In 1618, he held a General Assembly and pushed through Five Articles, which included practices that had been retained in England but largely abolished in Scotland, most controversially kneeling for the reception of communion. Although ratified, they created widespread opposition and resentment and were seen by many as a step back to Catholic practice.[7]

James VI was succeeded by his son Charles I in 1625.[8] Charles relied heavily on the bishops, particularly John Spottiswood, Archbishop of St. Andrews, eventually making him chancellor. At the beginning of his reign, Charles' revocation of alienated lands since 1542 helped secure the finances of the kirk, but it threatened the holdings of the nobility who had gained from the Reformation settlement.[9] Objects were fuelled by a widespread fear of "Popery",[10] but Catholicism was largely confined to some nobles and the Highlands and Islands.[11]

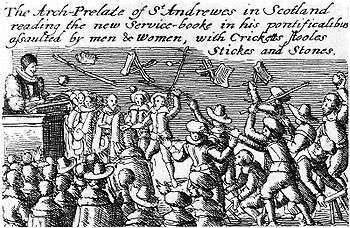

In 1635, without reference to a general assembly of the Parliament, the King authorised a book of canons that made him head of the Church, ordained an unpopular ritual and enforced the use of a new liturgy. When the liturgy emerged in 1637 it was seen as an English-style Prayer Book, resulting in anger and widespread rioting, said to have been set off with the throwing of a stool by one Jenny Geddes during a service in St Giles Cathedral.[12] The Protestant nobility put themselves at the head of the popular opposition. Representatives of various sections of Scottish society drew up the National Covenant on 28 February 1638, objecting to the King's liturgical innovations.[13] The King's supporters were unable to suppress the rebellion and the King refused to compromise. In December of the same year, at a meeting of the General Assembly in Glasgow, the Scottish bishops were formally expelled from the Church, which was then established on a full Presbyterian basis.[14]

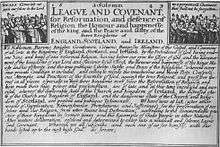

The Scots and the King both assembled armies and, after the two Bishop's Wars of 1639 and 1640, the Scots emerged the victors. Charles capitulated, leaving the Covenanters in independent control of the country. He was forced to recall the English Parliament, resulting in the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642.[15] The Covenanters sided with Parliament and in 1643 they entered into a Solemn League and Covenant, guaranteeing the Scottish Church settlement and promising further reform in England. The Westminster Confession of Faith, drawn up by English and Scottish ministers and agreed in 1645, became the subordinate standard of Covenanter doctrine.[16] By 1646 a Royalist campaign in the Highlands and the Royalists in England had been defeated and the King had surrendered.[17] Relations with the English Parliament and the increasingly independent English New Model Army became strained and control of Scotland country moved away from the hardline "Kirk Party" and fell under the control of those willing to compromise with the King. The resulting Engagement with the King led to a Second Civil War and a defeat for a Scottish invading army at the Battle of Preston, by the New Model Army led by Oliver Cromwell. After the coup of the Whiggamore Raid, the Kirk Party regained control in Scotland.[18]

Commonwealth

After the execution of the King in January 1649, England was declared a commonwealth and the Scots declared his son king as Charles II. The English responded with an invasion and, after defeats for the Scots at Dunbar in 1650 and Worcester in 1651, the English occupied the country in 1652, declaring Scotland part of the Commonwealth.[19] In the period after the defeat at Dunbar the Kirk became deeply divided, partly in the search for scapegoats for defeat. Different factions and tendencies produced rival resolutions and protests, which gave their names to the two major parties as the Resolutioners, who were willing to make an accommodation with royalism, and the more hard line Protesters who wished to purge the Kirk of such associations. Subsequently the divide between rival camps became almost irrevocable.[20] After 1655 both groups appointed permanent agents in London.[21]

The terms of the union promised that the Gospel would be preached and promised freedom of religion. The regime accepted Presbyterianism as a valid system, but did not accept that it was the only legitimate form of church organisation. The result was that although civil penalties no longer backed up its pronouncements, Kirk sessions and synods functioned much as before. The administration tended to favour the Protesters, largely because the Resolutioners were more inclined to desire a restoration of the monarchy and because the General Assembly, where they predominated, claimed independence from the state.[22] The act of holding public prayers for the success of the earl of Glencairn's insurrection against the regime, led in 1653, to the largely Resolutioner members of the Assembly being marched out of Edinburgh by an armed guard.[21] There were no more assemblies in the period of the Commonwealth and the Resolutioners met in informal "Consultations" of clergy. The universities, largely seen as a training school for clergy, were relatively well funded and came under the control of the Protestors, with Patrick Gillespie being made Principal at Glasgow.[22]

Toleration did not extend to Episcopalians and Catholics, but if they did not call attention to themselves they were largely left alone.[22] It did extend to sectaries, but the only independent group to establish itself in Scotland in this period were a small number of Quakers.[23] Some attempts were made to extend Protestantism to the largely Catholic, Gaelic-speaking Highlands and Islands. The first Gaelic catechism was published in 1653 and the first Psalm book in 1659.[24] In general the period of the Commonwealth was looked back on as one where Protestantism flourished. Ministers, now largely barred from politics, spent more time with their flocks and placed an emphasis on preaching that emulated the sectaries.[22] One Presbyterian noted that "there were more souls converted to Christ in that short period of time than in any season since the Reformation".[25]

Restoration

Restoration settlement

After the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, Scotland regained its kirk, but also the bishops. Under the Rescissory Act 1661, legislation was revoked back to 1633, removing the Covenanter gains of the Bishops' Wars. But an act passed later the same day renewed the discipline of kirk sessions, presbyteries and synods, suggesting that a compromise was possible.[26] The restoration of episcopacy was proclaimed by the Privy Council of Scotland on 6 September 1661.[27] James Sharp, minister of Crail, who was in London to represent the interests of the Resolutioners, changed sides and accepted the position of Archbishop of St. Andrews. He was consecrated along with Robert Leighton as Bishop of Dunblane and two other bishops. Soon an entire bench of bishops had been constructed.[26] During the parliamentary session of 1662 the Church of Scotland was restored as the national church and all office-holders were required to renounce the Covenants. Church ministers were forced to accept the new situation or lose their livings. Up to a third, at least 270, of the ministry refused. Many ministers chose voluntarily to abandon their own parishes rather than wait to be forced out by the government.[26] Most of the vacancies occurred in the south-west of Scotland, an area particularly strong in its Covenanting sympathies. Some of the ministers also took to preaching in the open fields in conventicles, often attracting thousands of worshippers.[28]

Toleration and persecution

The government responded with alternating policies of force and toleration. In 1663 an act was passed that declared dissenting minsters to be seditious persons and allowed the imposition of heavy fines on those who failed to attend the parish churches of the "King's curates". In 1666 a group of men from Galloway captured the government's local military commander and marched on Edinburgh. They were defeated at the Battle of Rullion Green and 50 prisoners were captured. 33 were executed, two after torture, and the rest were transported to Barbados. There were then a series of arrests of suspected persons. The rising resulted in the fall of the king's commissioner John Leslie, 1st Duke of Rothes.[29]

The new commissioner John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale attempted a more conciliatory policy, issuing Letters of Indulgence in 1669, 1672 and 1679. These allowed evicted ministers to return to their parishes, if they would avoid political dissent. 150 refused to accept the offer and some episcopalians were alienated by the compromise. Leighton, now bishop of Glasgow, attempted to engage with dissenters, but to no avail. The failure to reach an accommodation led to a return to severity. Preaching at a conventicle was made punishable by death and attendance was punishable by severe sanctions. In 1674 heritors and masters were made responsible for their tenants and servants and from 1677 they had to enter bonds for the conduct of everyone living on their land. In 1678 3,000 Lowland militia and 6,000 Highlanders, known as the "Highland Host", were billeted in the Covenanting shires as a form of punishment.[30]

Rebellion and the Killing Time

In 1679 a group of Covenanters killed Archbishop Sharp. The incident led to a rising that grew to 5,000 men. They were defeated by forces under James, Duke of Monmouth, the King's illegitimate son, at the Battle of Bothwell Bridge. Two ministers were executed and 250 followers shipped to Barbados, 200 drowning when their ship went down off Orkney. The rebellion eventually led to the fall of Lauderdale, who was replaced by the King's brother, the openly Catholic James, known in Scotland as the Duke of Albany.[31] The dissenters, led by Donald Cargill and Richard Cameron called themselves the Society People, but would be become known after their leader as the Cameronians. Reduced in number, hiding out in the moors, they became increasingly radical. On 22 June 1680, the Sanquhar Declaration was posted in Sanquhar, renouncing Charles II as king. Cameron was killed the next month. Cargill excommunicated the King, Duke of Albany and other royalists at the Torwood Conventicle and his followers now separated themselves from all other Presbyterian ministers. Cargill was captured and executed in May 1681.

The government passed a Test Act, forcing every holder of public office to take an oath of non-resistance. Eight Episcopal clergy and James Dalrymple, Lord President of the Court of Session resigned and the leading nobleman Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll was forced into exile. In 1684 the remaining Society People posted an Apologetical Declaration on several market crosses, which informed servants of the government that they pursued the lives of its members at the risk of their own. In response to this new element of outright political sedition, the Scottish Privy Council authorised extrajudicial field executions of those caught in arms or those who refused to swear loyalty to the King.[32] This more intense phase of persecution, later known in Protestant historiography as "the Killing Time", led to dissenters being summarily executed by the dragoons of James Graham, Laird of Claverhouse or sentenced to transportation or death by Sir George Mackenzie, the Lord Advocate.[33]

Glorious Revolution

Regime change

Charles died in 1685 and his brother succeeded him as James VII of Scotland (and II of England). James put Catholics in key positions in the government and even attendance at a conventicle was made punishable by death. He disregarded parliament, purged the Council and forced through religious toleration for Roman Catholics, alienating his Protestant subjects. The failure of an invasion, led by the Earl of Argyll and timed to co-ordinate with the Duke of Monmouth's rebellion in England, demonstrated the strength of the regime. However a riot in response to Louis XIV's Revocation of the Edict of Nantes indicated the strength of anti-Catholic feeling. The King's attempts to obtain toleration for Catholics led to the issuing of Letters of Indulgence in 1687, which also allowed freedom of worship to dissident Protestants, allowing "outed" Presbyterian ministers to return to their parishes. This did not extend to field conventicles and the Society People continued to endure hardship, with their last minister, James Renwick, being captured and executed in 1688.[33]

It was believed that the King would be succeeded by his daughter Mary, a Protestant and the wife of William of Orange, Stadtholder of the Netherlands, but when in 1688, James produced a male heir, James Francis Edward Stuart, it was clear that his policies would outlive him. An invitation by seven leading Englishmen led William to land in England with 40,000 men on 5 November.[33] In Edinburgh there were rumours of Orange plots and on 10 December the Lord Chancellor of Scotland, the Earl of Perth, quit the capital for Drummond Castle, planning an abortive escape to Ireland (he was later captured as he embarked for France). As rioters approached Holyrood Abbey they were fired on by soldiers, resulting in some deaths. The city guard was called out, but the Abbey was stormed by a large mob. The Catholic furnishings placed there when it was restored as a chapel for James were torn down and the tombs of the Stuart kings desecrated. A crowd of students burnt the Pope in effigy and took down the heads of executed Covenanters that were hanging above the city gates.[34] The crisis was resolved when James fled from England on 23 December, leading to an almost bloodless revolution. Although there had been no significant Scottish involvement in the coup, most members of the Scottish Privy Council went to London to offer their services to William. On 7 January 1689, they asked William to take over the responsibilities of government.[33]

Revolution settlement

William called a Scottish Convention, which convened on 14 March in Edinburgh. It was dominated by the Presbyterians. There was a faction that supported James, including many episcopalians, but these were divided by James' attempts to achieve tolerance for Roman Catholics. A letter from James, received on 16 March, contained a threat to punish all who rebelled against him and declaring the assembly illegal, resulted in his followers to abandon the Convention, leaving the Williamites dominant.[35] On 4 April the Convention formulated the Claim of Right and the Articles of Grievances. These suggested that James had forfeited the crown by his actions (in contrast to England, which relied on the legal fiction of an abdication) and offered it to William and Mary, which William accepted, along with limitations on royal power.[33] On 11 May William and Mary accepted the Crown of Scotland as co-regents, as William II and Mary II.[33] The final settlement, completed by William's Second parliament in 1690, restored Presbyterianism and abolished the bishops, who had generally supported James. Remaining ministers outed in 1662 were restored. The General Assembly of 1692 refused to reinstate even those Episcopalian ministers who pledged to accept Presbyterianism. However, the King issued two acts of indulgences in 1693 and 1695, allowing those who accepted him as king to return to the church and around a hundred took advantage of the offer. All but the hardened Jacobites would be given toleration in 1707, leaving only a small remnant of Jacobite episcopalians.[36]

Popular Protestantism

Scottish Protestantism in the seventeenth century was highly focused on the Bible, which was seen as infallible and the major source of moral authority. In the early part of the century the Genevan translation was commonly used.[37] In 1611 the Kirk adopted the Authorised King James Version and the first Scots version was printed in Scotland in 1633, but the Geneva Bible continued to be employed into the late seventeenth century.[38] Many Bibles were large, illustrated and highly valuable objects.[37] They often became the subject of superstitions, being used in divination.[39] Family worship was strongly encouraged by the Covenanters. Books of devotion were distributed to encourage the practice and minsters were encouraged to investigate whether this was being carried out.[40]

The seventeenth century saw the high-water mark of kirk discipline. Kirk sessions were able to apply religious sanctions, such as excommunication and denial of baptism, to enforce godly behaviour and obedience. In more difficult cases of immoral behaviour they could work with the local magistrate, in a system modelled on that employed in Geneva.[41] Public occasions were treated with mistrust and from the later seventeenth century there were efforts by kirk sessions to stamp out activities such as well-dressing, bonfires, guising, penny weddings and dancing.[42] Kirk sessions also had an administrative burden in the system of poor relief.[41] An act of 1649 declared that local heritors were to be assessed by kirk session to provide the financial resources for local relief, rather than relying on voluntary contributions.[43] By the mid-seventeenth century the system had largely been rolled out across the Lowlands, but was limited in the Highlands.[44] The system was largely able to cope with general poverty and minor crises, helping the old and infirm to survive and provide life support in periods of downturn at relatively low cost, but was overwhelmed in the major subsistence crisis of the 1690s, known as the seven ill years.[45] The kirk also had a major role in education. Statutes passed in 1616, 1633, 1646 and 1696 established a parish school system,[46] paid for by local heritors and administered by ministers and local presbyteries.[47] By the late seventeenth century there was a largely complete network of parish schools in the Lowlands, but in the Highlands basic education was still lacking in many areas.[48]

In the seventeenth century the pursuit of witchcraft was largely taken over by the kirk sessions and was often used to attack superstitious and Catholic practices in Scottish society. Most of the accused, some 75 per cent, were women, with over 1,500 executed, and the witch hunt in Scotland has been seen as a means of controlling women.[49] The most intense witch hunt was in 1661–62, which involved some 664 named witches in four counties. From this point prosecutions began to decline as trials were more tightly controlled by the judiciary and government, torture was more sparingly used and standards of evidence were raised. B. P. Levack suggests that there may also have been a growing scepticism and with relative peace and stability the economic and social tensions that contributed to accusation may have reduced. There were occasional local outbreaks like that in East Lothian in 1678 and 1697 at Paisley. The last recorded executions were in 1706 and the last trial in 1727. The British parliament repealed the 1563 Act in 1736.[50]

Catholicism

The numbers of practising Catholics probably continued to reduce in the seventeenth century and the organisation of the Church deteriorated.[51] Some were to convert to Roman Catholicism, as did John Ogilvie (1569–1615), who went on to be ordained a priest in 1610, later being hanged for proselytism in Glasgow and often thought of as the only Scottish Catholic martyr of the Reformation era.[52] An Irish Franciscan mission in the 1620s and 1630s claimed large numbers of converts, but these were confined to the Western Isles and had little impact on the mainland.[53] A college for the education of Scots clergy was opened at Madrid in 1633, and was afterwards moved to Valladolid. In 1653 the remaining five or six clergy were incorporated under William Ballantine as prefect of the mission.[54] There were a small number of Jesuits active in Strathgrass from the 1670s. The Pope appointed Thomas Nicolson as the first Vicar Apostolic over the mission in 1694 and the situation of Catholicism began to improve.[53] Nicholson divided Scotland into districts, each with its own designated priests and he undertook visitations to ensure the implementation of Papal legislation. In 1700 his Statuta Missionis, which included a code of conduct for priests and laymen, were approved by all the clergy.[55] By 1703 there were 33 Catholic clergy.[56]

References

Notes

- ↑ J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 102–4.

- ↑ M. F. Graham, "Scotland", in A. Pettegree, The Reformation World (London: Routledge, 2000), ISBN 0-415-16357-9, p. 414.

- ↑ Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community, pp. 120–1.

- ↑ Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community, pp. 121–33.

- ↑ P. Croft, King James (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), ISBN 0-333-61395-3, p. 11.

- ↑ A. Stewart, The Cradle King: A Life of James VI & I (London: Chatto and Windus, 2003), ISBN 0-7011-6984-2, pp. 51–63.

- 1 2 R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-415-27880-5, pp. 166–8.

- ↑ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0-14-013649-5, p. 202.

- ↑ Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, pp. 201–2.

- ↑ M. C. Fissel, The Bishops' Wars: Charles I's Campaigns Against Scotland, 1638–1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), ISBN 0-521-46686-5, pp. 269 and 278.

- ↑ M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0-7126-9893-0, p. 365.

- ↑ Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, p. 203.

- ↑ Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, p. 204.

- ↑ Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, pp. 205–6.

- ↑ Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, pp. 209–10.

- ↑ Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, pp. 211–12.

- ↑ Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, pp. 213–4.

- ↑ Mitchison, A History of Scotland, pp. 225–6.

- ↑ Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, pp. 221–6.

- ↑ Lynch, Scotland: a New History, pp. 279–81.

- 1 2 Lynch, Scotland: a New History, p. 285.

- 1 2 3 4 Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, pp. 227–8.

- ↑ R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 0-7486-0233-X, p. 66.

- ↑ Lynch, Scotland: a New History, p. 363.

- ↑ Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, p. 229.

- 1 2 3 Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, pp. 231–4.

- ↑ F. N. McCoy, Robert Baillie and the Second Scots Reformation (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 1974), ISBN 0-520-02447-8, p. 216.

- ↑ Mitchison, A History of Scotland, p. 253.

- ↑ Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, pp. 235–6.

- ↑ Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, pp. 237–8.

- ↑ Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, pp. 238–9.

- ↑ Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, pp. 239–41.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, pp. 241–5.

- ↑ Lynch, Scotland: a New History, p. 297.

- ↑ Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745, pp. 118–19.

- ↑ Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, pp. 252–3.

- 1 2 G. D. Henderson, Religious Life in Seventeenth-Century Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), ISBN 0-521-24877-9, pp. 1–4.

- ↑ Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community, pp. 192–3.

- ↑ Henderson, Religious Life in Seventeenth-Century Scotland, p. 12.

- ↑ G. D. Henderson, Religious Life in Seventeenth-Century Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), ISBN 0-521-24877-9, p. 8.

- 1 2 R. A. Houston, I. D. Whyte "Introduction" in R. A. Houston, I. D. Whyte, eds, Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-521-89167-1, p. 30.

- ↑ Houston and Whyte "Introduction", p. 34.

- ↑ Mitchison, A History of Scotland, p. 96.

- ↑ O. P. Grell and A. Cunningham, Health Care and Poor Relief in Protestant Europe, 1500–1700 (London: Routledge, 1997), ISBN 0-415-12130-2, p. 37.

- ↑ Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745, pp. 127 and 145.

- ↑ R. A. Houston, I. D. Whyte "Introduction" in R. A. Houston, I. D. Whyte, eds, Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-521-89167-1, p. 31.

- ↑ "School education prior to 1873", Scottish Archive Network, 2010, archived from the original on 3 July 2011.

- ↑ R. Anderson, "The history of Scottish Education pre-1980", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, Scottish Education: Post-Devolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1625-X, pp. 219–28.

- ↑ S. J. Brown, "Religion and society to c. 1900", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0-19-956369-1, p. 81.

- ↑ B. P. Levack, "The decline and end of Scottish witch-hunting", in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-7190-6024-9, pp. 166–80.

- ↑ J. T. Koch, Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1–5 (London: ABC-CLIO, 2006), ISBN 1-85109-440-7, pp. 416–7.

- ↑ J. Buckley, F. C. Bauerschmidt, T. Pomplun, eds, The Blackwell Companion to Catholicism (London: John Wiley & Sons, 2010), ISBN 1444337327, p. 164.

- 1 2 M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0712698930, pp. 365–6.

- ↑ C. G. Herbermann, ed., The Catholic Encyclopedia;: an International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic church; Volume 13 (Appleton, 1912), p. 620.

- ↑ M. C. C. Mairena, The Restoration of the Roman Catholic Hierarchy in Scotland PhD, Catholic University of America, 2008, ISBN 0549388338, pp. 56–60.

- ↑ Mackie, Lenman and Parker, A History of Scotland, pp. 298–9.

Bibliography

- Anderson, R., "The history of Scottish Education pre-1980", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, Scottish Education: Post-Devolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1625-X.

- Brown, S. J., "Religion and society to c. 1900", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0-19-956369-1.

- Croft, P., King James (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), ISBN 0-333-61395-3.

- Fissel, M. C., The Bishops' Wars: Charles I's Campaigns Against Scotland, 1638–1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), ISBN 0-521-46686-5.

- Graham, M. F., "Scotland", in A. Pettegree, The Reformation World (London: Routledge, 2000), ISBN 0-415-16357-9.

- Grell, O. P., and Cunningham, A., Health Care and Poor Relief in Protestant Europe, 1500–1700 (London: Routledge, 1997), ISBN 0-415-12130-2.

- Herbermann, C. G., ed., The Catholic Encyclopedia;: an International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic church; Volume 13 (Appleton, 1912).

- Henderson, G. D., Religious Life in Seventeenth-Century Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), ISBN 0-521-24877-9.

- Houston, R. A., Whyte, I. D., "Introduction" in R. A. Houston, I. D. Whyte, eds, Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-521-89167-1.

- Levack, B. P., "The decline and end of Scottish witch-hunting", in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-7190-6024-9.

- Lynch, M., Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0-7126-9893-0.

- Mackie, J. D., Lenman, B., and Parker, G., A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0-14-013649-5.

- Mairena, M. C. C., The Restoration of the Roman Catholic Hierarchy in Scotland, PhD, Catholic University of America, 2008, ISBN 0549388338

- McCoy, F. N., Robert Baillie and the Second Scots Reformation (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 1974), ISBN 0-520-02447-8.

- Mitchison, R., A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-415-27880-5.

- Mitchison, R., Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 0-7486-0233-X.

- Stewart, A., The Cradle King: A Life of James VI & I (London: Chatto and Windus, 2003), ISBN 0-7011-6984-2.

- Wormald, J., Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3.