Agriculture in Scotland in the early modern era

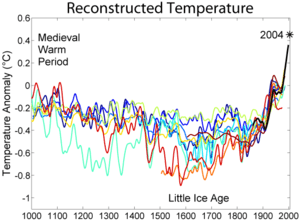

Agriculture in Scotland in the early modern era includes all forms of farm production in the modern boundaries of Scotland, between the establishment of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the mid-eighteenth century. This era saw the impact of the Little Ice Age, which peaked towards the end of the seventeenth century. Almost half the years in the second half of the sixteenth century saw local or national scarcity, necessitating the shipping of large quantities of grain from the Baltic. In the early seventeenth century famine was relatively common, but became rarer as the century progressed. The closing decade of the seventeenth century saw a slump, followed by four years of failed harvests, in what is known as the "seven ill years", but these shortages would be the last of their kind.

As feudal distinctions declined in the early modern era, the barons and tenants-in-chief merged to form a new identifiable group, the lairds. With the yeomen, these heritors were the major landholding orders. Others with property rights included husbandmen and free tenants. Many young people left home to become domestic and agricultural servants. The English invasions of the 1640s had a profound impact on the Scottish economy. Under the Commonwealth, the country was relatively highly taxed, but gained access to English markets. After the Restoration customs duties with England were re-established. Economic conditions were generally favourable, as land owners promoted better tillage and cattle-raising. After the Union of 1707 there was a conscious attempt to improve agriculture among the gentry and nobility. Introductions included haymaking, the English plough, foreign grasses, rye grass and clover, turnips and cabbages. Lands were enclosed, displacing the run rig system and free pasture. Marshes were drained, lime was put down, roads built, woods planted, drilling and sowing and crop rotation were introduced. The introduction of the potato to Scotland in 1739 greatly improved the diet of the peasantry. The resulting Lowland Clearances saw hundreds of thousands of cottars and tenant farmers from central and southern Scotland were forcibly removed.

Sixteenth century

Scotland is roughly half the size of England and Wales and has approximately the same amount of coastline, but only between a fifth and a sixth of the amount of the arable or good pastoral land, under 60 metres above sea level, and most of this is located in the south and east.[1] The early modern era saw the impact of the Little Ice Age, of colder and wetter weather, which peaked towards the end of the seventeenth century.[2] In 1564 there were thirty-three days of continual frost, with rivers and lochs freezing over.[3] This reduced the altitude at which crops could be grown and shortened the growing season by up to two months in extreme years.[4] One result was the abandonment of marginal land in the sixteenth century, as it became impossible to sustain agriculture, particularly in the uplands, but new settlements were created as a result of the opening up of hunting reserves like Ettrick Forest and less desirable low-lying land was also settled, often incorporating features into their names such as bog, marsh and muir.[2] Almost half the years in the second half of the sixteenth century saw local or national scarcity, necessitating the shipping of large quantities of grain from the Baltic,[5] referred to as Scotland's "emergency granary". This was particularly from Poland through the port of Danzig, but later Königsberg and Riga, shipping Russian grain, and Swedish ports, would become important. The trade was so significant that Scottish colonies were established in these ports.[6]

While the feudal tenures of barons were increasingly nominal [7] local tenants-in-chief, who held legally held their land directly from the king and who by the sixteenth century were often the major local landholders in an area, grew in significance. As feudal distinctions declined, the barons and tenants-in-chief merged to form a new identifiable group, the lairds,[8] roughly equivalent to the English gentlemen.[9] Below the lairds were a variety of groups, often ill-defined. These included yeomen, later characterised by Walter Scott as "bonnet lairds", often owning substantial land.[10] The practice of feuing (by which a tenant paid an entry sum and an annual feu duty, but could pass the land on to their heirs) meant that the number of people holding heritable possession of lands, which had previously been controlled by the church or nobility, expanded.[11] These and the lairds probably numbered about 10,000 by the seventeenth century[10] and became what the government defined as heritors, on whom the financial and legal burdens of local government increasingly fell.[12]

Below the substantial landholders were those engaged in subsistence agriculture, who made up the majority of the working population.[13] Those with property rights included husbandmen, lesser landholders and free tenants.[14] Below them were the cottars, who often shared rights to common pasture, occupied small portions of land and participated in joint farming as hired labour. Farms also might have grassmen, who had rights only to grazing.[14] By the early modern era in Lowland rural society, as in England, many young people, both male and female, left home to become domestic and agricultural servants.[15] Women acted as an important part of the workforce. As well as moving away from their families as farm servants, married women worked with their husbands around the farm, taking part in all the major agricultural tasks. They had a particular role as shearers in the harvest, forming most of the reaping team of the bandwin.[16]

Most farming was based on the Lowland fermtoun or Highland baile, settlements of a handful of families that jointly farmed an area.[17] The most common system was based on infield and outfield agriculture. The infield was the best land, close to housing. It was farmed continuously and most intensively, receiving most of the manure. Crops were usually bere (a form of barley), oats and sometimes wheat, rye and legumes. The more extensive outfield was used largely for oats. It was fertilised from the overnight folding of cattle in the summer and was often left fallow to recover its fertility. In fertile regions the infield could be extensive, but in the uplands it might be small, surrounded by large amounts of outfield. In coastal areas fertiliser included seaweed and around the major burghs urban refuse was used. Yields were fairly low, often around three times the quantity of seed sown, although they could reach twice that yield on some infields.[18]

The area of arable land farmed by a family was notionally suitable for two or three plough teams, allocated in runrigs.[17] Runrigs, were a ridge and furrow pattern, similar to that used in parts of England, with alternating "runs" (furrows) and "rigs" (ridges).[19] They usually ran downhill so that they included both wet and dry land, helping to offset some of the problems of extreme weather conditions. Most ploughing was done with a heavy wooden plough with an iron coulter, pulled by oxen, which were more effective on heavy soils and cheaper to feed than horses.[17] They were usually pulled by a team of eight oxen,[20] which would have taken four men to operate and only covered half an acre a day.[21] In the late sixteenth century population growth in the west Highlands prompted an abandonment of ploughing in favour of more intensive cultivation methods using spades and foot ploughs (cas chrom) with lazy beds, which produced larger furrows with narrower channels between and allowed arable cultivation[18] in locations where ploughing would have been impossible.[22] Pasture was often accessed by shieling-grounds, with shelters made of stone or turf, used for the grazing of cattle in summer. These would often be distant from the main settlements in the Lowlands, but might be relatively close in the more remote Highlands.[23] All farms combined livestock with arable farming, with cattle and sheep and goats in parts of the Highlands and all farms growing some grain. However, there was some specialisation, with arable most important in the East and there was a tradition of sheep farming in the eastern Borders dating back to the arrival of new monastic orders in the twelfth century, which continued after the secularisation of the monasteries.[18]

Seventeenth century

In the early seventeenth century famine was relatively common, with four periods of famine prices between 1620 and 1625. The English invasions of the 1640s had a profound impact on the Scottish economy, with the destruction of crops and the disruption of markets resulting in some of the most rapid price rises of the century.[24] Under the Commonwealth, the country was relatively highly taxed, but gained access to English markets.[25] After the Restoration the formal frontier with England was re-established, along with its customs duties. Economic conditions were generally favourable from 1660 to 1688, as land owners promoted better tillage and cattle-raising.[26] Arable farming grew in the Lowlands, particularly around the growing urban centres like Edinburgh. Agricultural improvement began in the late seventeenth century in the Lothians and central Scotland, with the use of lime to combat the acidity of the soil, trees were planted, new crops introduced including sown grass and the rotation of crops.[18] Three acts of parliament passed in 1695 allowed the consolidation of runrigs and the division of commonties and common pasture[27] and small scale enclosures began to be carried out.[18]

Highlanders had been droving cattle on the hoof to the Lowlands since at least the sixteenth century.[22] By the 1680s the trade had expanded to the larger English markets.[27] Cattle were crossed with larger Irish breeds and large parks were constructed by Galloway landholders to hold and fatten cattle.[18] By the end of the century the drovers roads had become established, stretching down from the Highlands through south-west Scotland to north-east England.[28] From there some were driven to Norfolk to be fattened before being slaughtered in Smithfield for the London population.[22] Specialisation continued, with the increasing commercialisation of sheep farming in the Borders as English markets opened up after the Union of Crowns in 1603 and dairy becoming a feature of farming in the western Lowlands.[18]

The closing decade of the seventeenth century saw the generally favourable economic conditions that had dominated since the Restoration come to an end. There was a slump in trade with the Baltic and France from 1689–91, caused by French protectionism and changes in the Scottish cattle trade, followed by four years of failed harvests (1695, 1696 and 1698-9), known as the "seven ill years".[29] The result was severe famine and depopulation, particularly in the north.[30] The famines of the 1690s were seen as particularly severe, partly because famine had become relatively rare in the second half of the seventeenth century, with only one year of dearth (in 1674) and the shortages of the 1690s would be the last of their kind.[31]

Early eighteenth century

Climatic conditions began to improve in the early eighteenth century, although there were still bad years, like that of 1739–41.[4] Increasing contacts with England after the Union of 1707 led to a conscious attempt to improve agriculture among the gentry and nobility. The Society of Improvers was founded in 1723, including in its 300 members dukes, earls, lairds and landlords.[32] Before the eighteenth century English books on husbandry had been available or reprinted in Scotland, but in the eighteenth century there were increasing numbers of titles published by Scottish authors in Scotland.[33] In the first half of the century these changes were limited to tenanted farms in East Lothian and the estates of a few enthusiasts, such as John Cockburn and Archibald Grant. Not all were successful, with Cockburn driving himself into bankruptcy, but the ethos of improvement spread among the landed classes.[18]

Haymaking was introduced along with the English plough and foreign grasses, the sowing of rye grass and clover. Turnips and cabbages were introduced, lime was put down, marshes were drained, roads built and woods planted. Drilling and sowing and crop rotation were introduced. The introduction of the potato to Scotland in 1739 greatly improved the diet of the peasantry. Enclosures began to displace the runrig system and free pasture, creating the landscape of largely rectangular fields that characterises the Lowland Scottish landscape today.[32] New farm buildings, often based on designs in patterns books, replaced the fermtoun and regional diversity was replaced with a standardisation of building forms. Smaller farms retained the linear outline of the longhouse, with dwelling house, barn and byre in a row, but in larger farms a three- or four-sided layout became common, separating the dwelling house from barns and servants quarters.[34] There were also organisational changes that would have long term consequences, including the commutation of payments in kind for those in money, the granting of longer leases and the consolidation of smaller holdings.[18]

Although some estate holders improved the quality of life of their displaced workers,[32] the Agricultural Revolution led directly to what is increasingly becoming known as the Lowland Clearances,[35] when hundreds of thousands of cottars and tenant farmers from central and southern Scotland were forcibly moved from the farms and small holdings their families had occupied for hundreds of years. Many small settlements were dismantled, their occupants forced either to the new purpose-built villages built by the landowners such as John Cockburn's Ormiston or Archibald Grant's Monymusk[36] on the outskirts of the new ranch-style farms, to the new industrial centres of Glasgow, Edinburgh, or northern England. Tens of thousands of others emigrated to Canada or the United States, finding opportunities there to own and farm their own land.[32]

References

Notes

- ↑ E. Gemmill and N. J. Mayhew, Changing Values in Medieval Scotland: a Study of Prices, Money, and Weights and Measures (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), ISBN 0521473853, pp. 8–10.

- 1 2 I. D. White, "Rural Settlement 1500–1770", in M. Lynch, ed., Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), ISBN 0199693056, pp. 542–3.

- ↑ J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748614559, pp. 8–11.

- 1 2 T. C. Smout, "Land and sea: the environment", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0191624330, p. 22-3.

- ↑ J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 166–8.

- ↑ H. H. Lamb, Climatic History and the Future (London: Taylor & Francis, 1977), ISBN 0691023875, p. 472.

- ↑ J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 30–3.

- ↑ R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, p. 79.

- ↑ A. Grant, "Service and tenure in late medieval Scotland 1324–1475" in A. Curry and E. Matthew, eds, Concepts and Patterns of Service in the Later Middle Ages (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2000), ISBN 0851158145, pp. 145–65.

- 1 2 R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, p. 80.

- ↑ J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 51–2.

- ↑ J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748614559, p. 331.

- ↑ A. Grant, "Late medieval foundations", in A. Grant and K. J. Stringer, eds, Uniting the Kingdom?: the Making of British History (London: Routledge, 1995), ISBN 0415130417, p. 99.

- 1 2 R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, p. 82.

- ↑ I. D. Whyte, "Population mobility in early modern Scotland", in R. A. Houston and I. D. Whyte, Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0521891671, p. 52.

- ↑ R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, pp. 86–8.

- 1 2 3 J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 41–55.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 I. D. Whyte, "Economy: primary sector: 1 Agriculture to 1770s", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 206–7.

- ↑ I. D. Whyte and K. A. Whyte, The Changing Scottish Landscape: 1500–1800 (London: Taylor & Francis, 1991), ISBN 0415029929, p. 61.

- ↑ R. McKitterick and D. Abulafia, eds, The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 1024-c. 1198 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), ISBN 0521853605, p. 590.

- ↑ G. Donaldson, Scotland: the Shaping of a Nation (David & Charles, 2nd edn., 1980), ISBN 0715379755, p. 231.

- 1 2 3 I. D. Whyte, "Economy of the Highlands and Islands: 1 to 1700", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 202–3.

- ↑ P. Dixon, "Rural settlement: I Medieval", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 540–2.

- ↑ R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805, pp. 291–3.

- ↑ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 226–9.

- ↑ C. A. Whatley, Scottish Society, 1707–1830: Beyond Jacobitism, Towards Industrialisation (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), ISBN 071904541X, p. 17.

- 1 2 K. Bowie, "New perspectives on pre-union Scotland" in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0191624330, p. 314.

- ↑ R. A. Houston, Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), ISBN 0521890888, p. 16.

- ↑ R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805, pp. 291–2 and 301-2.

- ↑ K. J. Cullen, Famine in Scotland: The “Ill Years” of the 1690s (Edinburgh University Press, 2010), ISBN 0748638873.

- ↑ R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805, pp. 254–5.

- 1 2 3 4 J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 288–91.

- ↑ H. Holmes, "Agricultural publishing", in W. Bell, S. W. Brown, D. Finkelstein, W. McDougall and A. McCleery. The Edinburgh History of the Book in Scotland: Enlightenment and Expansion 1707–1800 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), ISBN 0748619127, p. 503.

- ↑ A. Fenton, "Housing: rural Lowlands, before and after 1770s", in M. Lynch, ed., Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), ISBN 0199693056, pp. 321–3.

- ↑ R. A. Houston and I. D. Whyte, Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-521-89167-1, pp. 148–151.

- ↑ D. Ross, Scotland: History of a Nation (Lomond Books, 2000), ISBN 0947782583, p. 229.

Bibliography

- Bowie, K., "New perspectives on pre-union Scotland" in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0191624330.

- Cullen, K. J., Famine in Scotland: The “Ill Years” of the 1690s (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010), ISBN 0748638873.

- Dawson, J. E. A., Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748614559.

- Dixon, P., "Rural settlement: I Medieval", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- Donaldson, G., Scotland: the Shaping of a Nation (David & Charles, 2nd edn., 1980), ISBN 0715379755.

- Fenton, A., "Housing: rural Lowlands, before and after 1770s", in M. Lynch, ed., Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), ISBN 0199693056.

- Gemmill, E. and Mayhew, N. J., Changing Values in Medieval Scotland: a Study of Prices, Money, and Weights and Measures (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), ISBN 0521473853.

- Grant, A., "Late medieval foundations", in A. Grant and K. J. Stringer, eds, Uniting the Kingdom?: the Making of British History (London: Routledge, 1995), ISBN 0415130417.

- Grant, A., "Service and tenure in late medieval Scotland 1324–1475" in A. Curry and E. Matthew, eds, Concepts and Patterns of Service in the Later Middle Ages (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2000), ISBN 0851158145.

- Holmes, H., "Agricultural publishing", in W. Bell, S. W. Brown, D. Finkelstein, W. McDougall and A. McCleery, eds, The Edinburgh History of the Book in Scotland: Enlightenment and Expansion 1707–1800 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), ISBN 0748619127.

- Houston, R. A. and Whyte, I. D., Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-521-89167-1.

- Houston, R. A., Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), ISBN 0521890888.

- Lamb, H. H., Climatic History and the Future (London: Taylor & Francis, 1977), ISBN 0691023875.

- Mackie, J. D., Lenman, B. and Parker, G., A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495.

- McKitterick, R. and Abulafia, D., eds, The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 1024-c. 1198 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), ISBN 0521853605.

- Mitchison, R., A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805.

- Mitchison, R., Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X.

- Ross, D., Scotland: History of a Nation (Lomond Books, 2000), ISBN 0947782583.

- Smout, T. C., "Land and sea: the environment", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0191624330.

- Whatley, C. A., Scottish Society, 1707–1830: Beyond Jacobitism, Towards Industrialisation (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), ISBN 071904541X.

- White, I. D., "Rural Settlement 1500–1770", in M. Lynch, ed., Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), ISBN 0199693056.

- Whyte, I. D. and Whyte, K. A., The Changing Scottish Landscape: 1500–1800 (London: Taylor & Francis, 1991), ISBN 0415029929.

- Whyte, I. D., "Economy of the Highlands and Islands: 1 to 1700", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- Whyte, I. D., "Economy: primary sector: 1 Agriculture to 1770s", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- Whyte, I. D., "Population mobility in early modern Scotland", in R. A. Houston and I. D. Whyte, Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0521891671.

- Wormald, J., Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763.